FPC Antenna 2.4 GHz Layout Clearance & Tuning in Practice

Dec 18,2025

This schematic highlights the unique challenge of FPC antennas compared to rubber duckies due to their internal placement: balancing predictable RF performance with assembly feasibility through precise layout and clearance design within confined mechanical space, avoiding resonance shifts caused by nearby metal.

When you design a compact Wi-Fi or IoT device, the FPC antenna seems almost too simple — a thin flex strip with a coax tail. Yet every millimeter of placement and clearance decides whether your prototype passes FCC tests or struggles to link through a single wall.

Unlike the rubber-duck antennas often shown in TEJTE’s indoor coverage guide, an internal FPC sits just millimeters from metal frames and batteries. One misplaced screw can shift resonance by 100 MHz. Real-world reliability comes from balancing mechanical freedom with RF predictability — enough distance from metal, but still practical for assembly.

This article follows a full path from concept to production order:

layout keep-out to pigtail loss budget to quick VNA check to ordering fields and acceptance. It’s written for engineers and buyers who want their first EVT build to connect cleanly, not after weeks of retuning.

Which FPC Antenna Size and Feed Style Fits Your Device and Bands?

Choosing the right FPC antenna starts with frequency band and mechanical envelope. For 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi, most designs use a 35–45 mm length and 6–10 mm width. Dual-band (2.4/5 GHz) parts extend to ≈ 55 mm, while tri-band 6 GHz units can reach 65 mm.

If your product uses similar geometry to the examples in the Omnidirectional Wi-Fi Antenna Optimization article, aim for comparable gain (2–3 dBi) and polarization consistency.

Tip: keep the adhesive face perfectly flat. Once the copper inside a flex creases, impedance shifts and VSWR rarely returns to spec.

Feed styles:

- Center-feed — best for top-edge placement in plastic housings.

- End-feed — fits narrow side panels or bezels.

- Dual feed — required for MIMO; ensure equal cable exit angles and strain relief.

Adhesive grades differ more than most assume. PET-based tape softens near 80 °C, whereas acrylic types survive 120 °C. Match it to your environment, not just cost.

If enclosure shape is fixed and volume is high, a PCB antenna may cut unit cost. But for early Wi-Fi-7 or IoT prototypes, FPCs allow fast tuning without board re-spins, exactly why many TEJTE customers prototype with them first.

Map Module Bands to Form Factor and Cable Exit

Every Wi-Fi or Bluetooth module lists its supported bands and feed impedance. Align that data with your FPC form factor and cable exit.

- 2.4 GHz-only modules: use a single FPC with 1.13 mm cable and IPEX connector.

- Dual-band 2.4 + 5 GHz: choose dual-feed FPCs or two independent units for MIMO.

- 6 GHz Wi-Fi 6E/7: keep pigtails under 150 mm and maintain solid ground near the feed.

Many modules show conservative clearances in datasheets. You can often reclaim 10–15 % of space if your housing is mostly plastic and the FPC window remains open.

Select Adhesive Grade, Bend Radius & Strain Relief

Flex circuits aren’t meant to fold sharply. For a 1-oz copper PI film, maintain a minimum bend radius ≈ 5 × thickness. Over-bend once, and vibration tests will expose intermittent opens.

Integration checklist:

- Route the cable so the connector pulls straight, never sideways.

- Reinforce exits with Kapton or cloth tape.

- Smooth curves beat sharp creases every time.

Such details save more debugging time than any last-minute “retune.”

How Do You Define the RF Keep-Out So the FPC Won’t Detune Near Metal?

| Nearby Part | Min Distance (mm) | Typical Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Metal frame / battery | ≥ 15 | < 10 mm shift > 100 MHz detune risk |

| Shield can top | ≥ 10 | couples harmonics near 4.8 GHz |

| Ground plane edge | ≥ 5 | adds capacitance to return loss rise |

| Heat-sink / motor housing | ≥ 20 | eddy currents absorb field power |

If space is tight, offset reduction can be balanced by enlarging the plastic window above the FPC. That’s a trick often mentioned in TEJTE’s RF Coaxial Cable Guide — mechanical trade-offs shape real RF results.

When embedding behind a metal lid or LCD, leave a non-conductive window ≈ 25 × 40 mm. Thick ABS (> 1.5 mm) reduces gain slightly; thinner PC or PET covers perform better.

Plastic Window Design in Metal Housings

Many industrial enclosures are fully shielded, leaving only a logo area or vent as an RF exit.

Rules worth noting:

- Window width ≥ 1.5 × FPC length for near-free-space gain.

- Center the window over the feed region.

- Avoid painted or metallized layers — chrome pigments can cost 2–3 dB of gain.

One TEJTE customer recovered Wi-Fi performance simply by stripping decorative coating from the window — a zero-cost fix that RF simulations rarely predict.

Will Your U.FL / IPEX Pigtail Length and Type Erase the Link Margin?

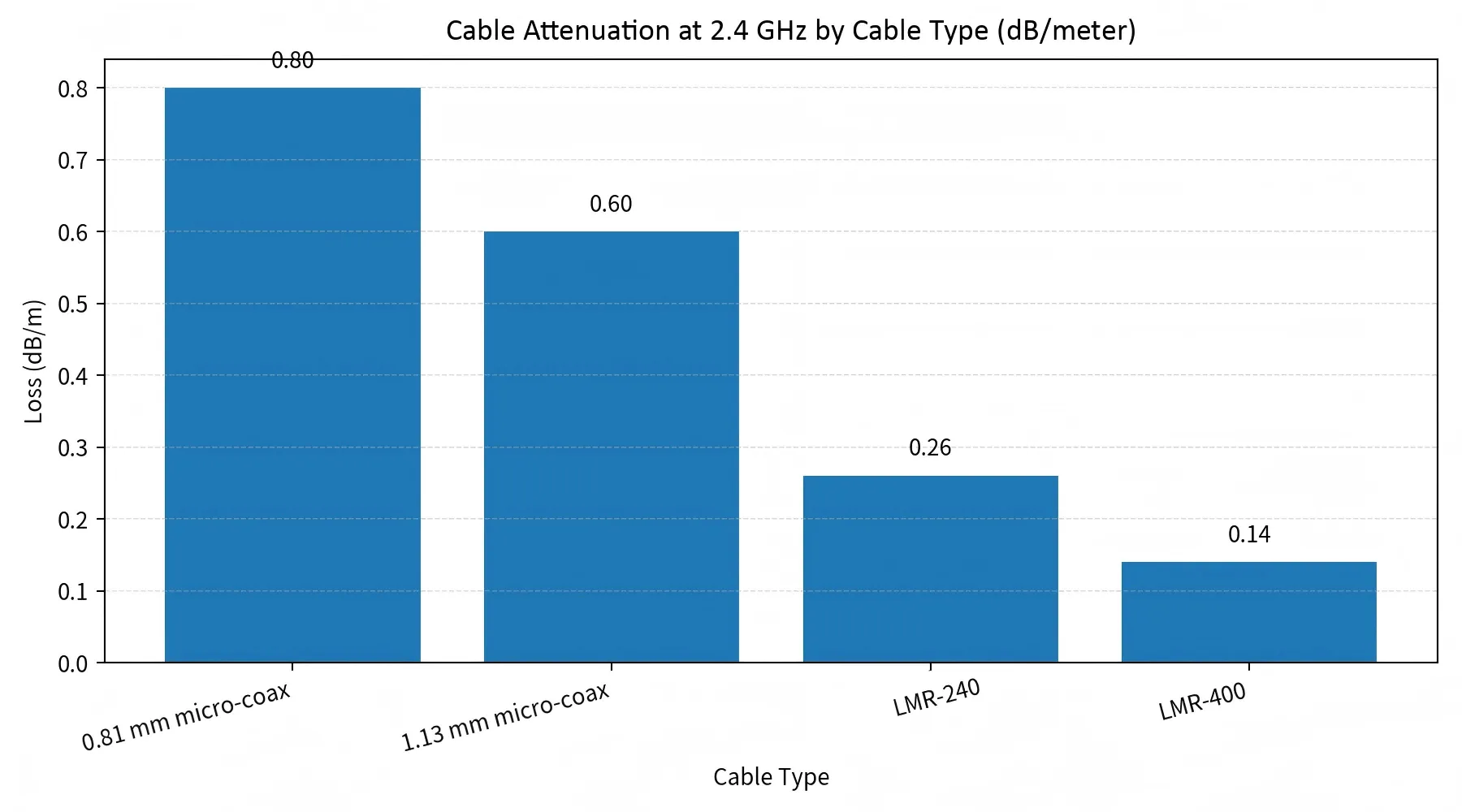

This performance comparison chart helps engineers understand the “silent” impact of feeder selection on link budget. It quantifies the loss of different cables, emphasizing that in FPC antenna systems, overly long or high-loss micro-coax jumpers can significantly erode effective radiated power (EIRP), a critical factor to watch in indoor RF design.

| Cable Type | Loss (dB/m) | Max Recommended Length | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.81 mm micro-coax | 0.80 | ≤ 0.25 m | Tight IoT modules |

| 1.13 mm micro-coax | 0.60 | ≤ 0.30 m | Standard Wi-Fi dongles |

| LMR-240 | 0.26 | ≤ 1.5 m | Bench testing jumpers |

| LMR-400 | 0.14 | ≤ 3 m | External antenna links |

Each connector pair — module to pigtail to bulkhead to antenna — adds ≈ 0.15 dB loss. Two extra adapters can steal half a decibel of link margin, enough to show up as RSSI drops in field tests.

When throughput falls, measure from radio port to FPC tip on a VNA first. It quickly reveals whether the issue lives in the cable chain or in the antenna itself.

Count Connector Pairs & VSWR Impact

A single U.FL connector typically shows a –20 dB return loss (VSWR ≈ 1.22). Chain two and composite VSWR hits ≈ 1.5 — already losing 1–1.5 dB effective gain.

Use direct-mounted IPEX tails where possible, avoid unnecessary bulkheads, and keep the connector orientation consistent with the RF path. In long-life IoT products, fewer interfaces mean fewer field failures.

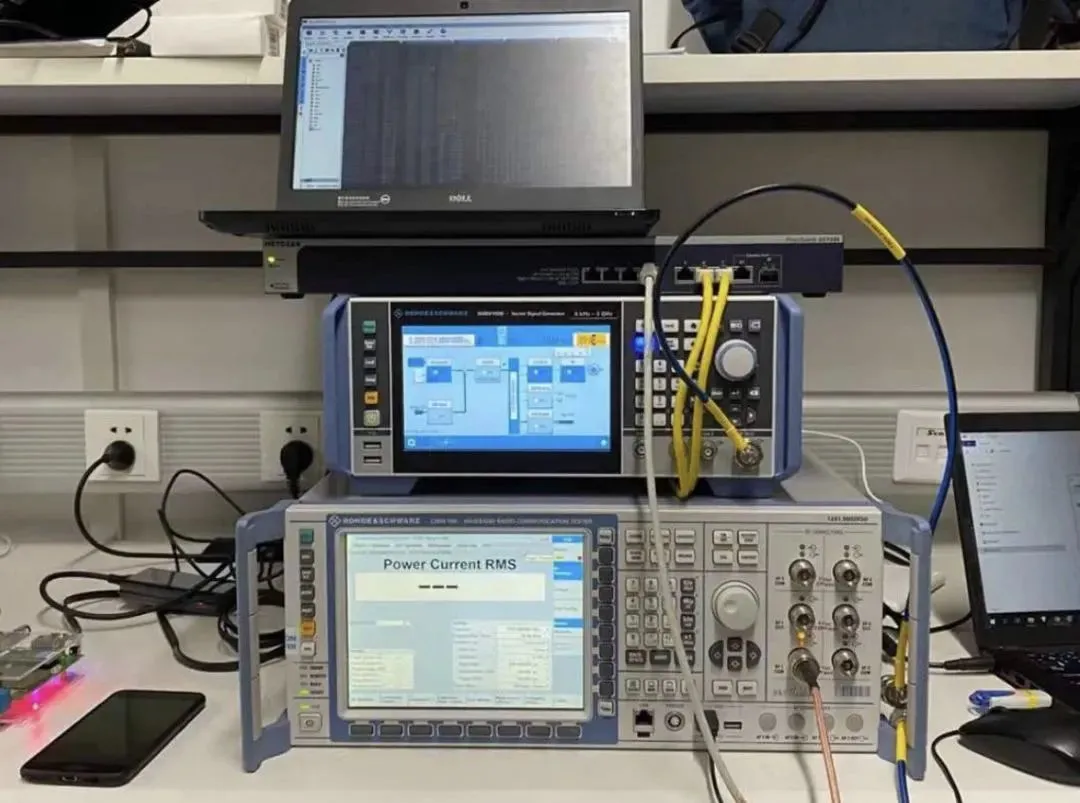

Can You Hit 2.4 GHz Resonance Without a Full Anechoic Chamber?

This diagram illustrates that effective antenna performance validation is possible without an expensive anechoic chamber. It guides engineers to check the antenna’s resonant frequency and matching state through simple VNA measurements, and to assess the sensitivity of the antenna layout to the surrounding environment by observing frequency shifts caused by factors like a hand approaching.

You don’t need a million-dollar chamber to confirm your FPC antenna is tuned correctly. A careful bench setup can tell 80 % of the story if you know what to look for.

Start with a vector network analyzer (VNA). Connect through a short, well-calibrated coax (ideally <10 cm). Measure the return loss across 2.3–2.5 GHz. A clean dip around 2.42 GHz with –10 dB or better means the antenna is in tune.

For fine adjustment, you can modify matching pads near the feed or use small copper shims to adjust capacitance. Even 1 mm of trace trimming may shift resonance by 30–40 MHz. TEJTE’s RF Connector Selection Guide explains similar detuning effects when connectors misalign on 2.4 GHz test benches.

Quick sanity check: place your hand 10 cm away from the antenna. If return loss shifts more than 5 MHz, the surrounding environment is too sensitive — you’ll need better isolation or a bigger plastic window.

When you have limited tools, run quick OTA “smoke tests”: measure RSSI on a laptop while moving 2–3 m away from the device. A stable ±2 dB signal swing across orientations usually signals good matching.

Hand-Detune and On-Bench OTA Tests

Simple tricks still reveal valuable insight. Hold the product in normal user positions — landscape, portrait, or on a metal table. If Wi-Fi throughput collapses when you touch the housing, your keep-out or ground-clearance zone is too tight.

In many IoT gateways tested by TEJTE, expanding clearance by just 5 mm recovered up to 3 dB RSSI improvement. That’s roughly double link reliability under weak signal conditions.

No chamber needed — only discipline in keeping test distances and conditions consistent.

Where Should You Route RF Cables to Avoid Coupling and Noise Pickup?

Cable routing can make or break your antenna efficiency. Even if your FPC antenna is tuned perfectly, a poorly routed coax can pick up digital noise or couple to high-current lines.

Here are practical layout habits we’ve seen succeed across hundreds of TEJTE builds:

- Cross signal lines at 90° rather than running parallel.

- Avoid tight loops; long parallel traces act as unintended antennas.

- Maintain clear return paths — the coax shield should always see a clean ground near the radio.

- Clamp cables with adhesive mounts rather than glue — easier for EVT rework.

If you’ve ever debugged random packet drops, odds are your cable sat next to a 5 V boost converter line. Moving it 10 mm away can eliminate the noise entirely.

For multi-antenna systems, match the routing length and symmetry between pigtails. MIMO chains suffer phase mismatch if one cable meanders while the other takes a straight path.

This principle echoes what TEJTE covers in its Outdoor Omni Antenna Mounting Guide — symmetry and clearance apply indoors just as much as on rooftops.

Cable Clamps and Adhesives During Prototyping

During EVT or DVT, prioritize non-destructive cable fixing. Replace hot glue with low-residue tapes or clamp mounts. These allow you to reroute easily during tuning iterations without damaging the flex or the housing.

Label each cable’s route for reassembly; engineers often forget which version passed the best OTA results, causing lost time before certification.

Do You Need Coexistence Rules for 2.4/5/6 GHz and MIMO on Tiny Boards?

Yes — because every extra antenna becomes both a partner and a rival. In a compact enclosure, FPC antennas share space with LTE, GPS, or 5G traces, and crosstalk happens faster than you expect.

For dual FPC setups:

- Keep ≥15 mm spacing edge-to-edge for isolation >15 dB.

- Target >20 dB isolation for clean MIMO throughput.

- Maintain orthogonal orientation (one vertical, one horizontal) for polarization diversity.

If your board area can’t meet those numbers, move one antenna to the opposite side or to a short external whip. As seen in TEJTE’s Rubber Ducky Antenna Guide, switching one chain to an external SMA whip often improves total throughput rather than reducing it.

When Internal FPC Loses to a Short External Rubber Duck

Internal antennas are elegant, but sometimes physics wins.

If you operate in a heavy-metal or high-humidity enclosure, a rubber-duck antenna may outperform any embedded FPC.

For example, during one TEJTE customer test, replacing an internal FPC with a 3 dBi rubber duck raised throughput by 28 % at 10 m distance. The improvement came entirely from cleaner impedance and lower near-field absorption.

So if you’re repeatedly failing OTA or certification margins, it’s not defeat to go external — it’s pragmatism.

Can You Validate Coverage Fast Before Freezing the BOM?

RSSI and Throughput Snapshots

Run Wi-Fi signal strength scans at 1 m, 3 m, and 10 m in three orientations: front, back, side. Plot the RSSI in dB to visualize dead zones. A healthy FPC antenna shows less than 5 dB difference across planes.

To quantify link reliability, perform short throughput bursts (e.g., iperf3 tests). If data rate drops >20 % in any direction, suspect enclosure symmetry or detuning near edges.

Micro-tip: always record environmental humidity and nearby metal furniture — both can skew small OTA tests.

Cable-First Fault Isolation

When a unit fails RSSI checks, resist retuning the antenna first. Instead, swap cables step by step:

- Replace the pigtail with a known-good one.

- Reseat all IPEX connectors with ESD-safe tweezers.

- Only then, replace the FPC itself.

Roughly half of all “antenna failures” in pilot runs trace back to connector mating errors or damaged micro-coax.

(This process complements the test logic found in TEJTE’s RF Cable Guide — isolate losses before assuming the hardware is bad.)

How Should You Order So the PO Is Manufacturable and Test-Friendly?

FPC Ordering & Acceptance Checklist

| Field | Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Size | L × W of active flex area | 45 mm × 8 mm |

| Cable type / length | 1.13 mm micro-coax / 150 mm | match tested prototype |

| Connector | IPEX MHF I female | must fit module socket type |

| Adhesive | Acrylic 120 °C grade | high-temp model |

| Bend radius | ≥ 5× thickness | avoid sharp creases |

| Keep-out window | 25 × 40 mm PC area | test verified |

| Label & trace | “FPC-2G4-45mm” | printed near tail |

| Compliance | RoHS / REACH | add in supplier quote |

| Sample lot | 5 pcs with VNA plots | verify before mass order |

| VNA pass | –10 dB @ 2.4 GHz | test condition summary |

| OTA pass | RSSI ±3 dB variance | 3D orientation test |

| Packaging | ESD zip bag | include label & desiccant |

| RMA marks | Batch + QC seal | simplifies feedback loop |

What Changed in 2024–2025 for Internal Wi-Fi Antennas

Over the last two years, the internal antenna landscape has shifted fast — especially for FPC antenna users. Wi-Fi 6E and Wi-Fi 7 modules now expose calibrated chain data, letting you predict gain and efficiency earlier in development.

In practical terms, that means less time in the chamber. Many module vendors now provide per-chain calibration factors, so you can check expected EIRP without complex post-processing. TEJTE’s engineering team has seen this cut OTA tuning time by nearly 40% in some customer builds.

At the same time, industrial and consumer products have grown denser. Displays, batteries, and shields are all closer together, leaving only 5–10 mm clearance for FPC mounting. As a result, ground-clearance rules and predictable cable paths have become even stricter. The RF window you define during CAD modeling must remain reserved through all mechanical revisions.

Designers who respect those clearances early often pass FCC testing in one round — the ultimate cost saver.

FPC Keep-Out & Detune Risk Estimator

When you can’t simulate full 3D fields, use a heuristic approach to estimate detune risk. This simple model blends geometry and cable loss — handy during layout review.

Inputs

| Parameter | Symbol | Unit | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | freq_GHz | GHz | [2.4, 5, 6] |

| Nearest metal distance | metal_offset_mm | mm | 5 – 30 |

| Plastic window shortest edge | window_size_mm | mm | 20 – 50 |

| Ground clearance | ground_clear_mm | mm | 2 – 10 |

| Cable type | cable_type | - | [0.81, 1.13, LMR-240, LMR-400] |

| Cable length | cable_len_m | m | 0.05 – 1.5 |

| Connector pairs | connector_pairs | - | 1 – 4 |

Heuristic risk formula

risk = w1·(1/metal_offset_mm) + w2·(1/ground_clear_mm) + w3·(1/window_size_mm) + w4·(loss_per_m·cable_len_m + 0.15·connector_pairs)

Approximate losses @2.4 GHz:

- 0.81 mm ≈ 0.80 dB/m

- 1.13 mm ≈ 0.60 dB/m

- LMR-240 ≈ 0.26 dB/m

- LMR-400 ≈ 0.14 dB/m

- Connector ≈ 0.15 dB/pair

Interpretation

| Risk Score | Meaning | Action |

|---|---|---|

| ≤ 0.4 | Safe | Proceed |

| 0.4 – 0.7 | Moderate | Adjust window / shorten cable |

| > 0.7 | High | Redesign or switch to external antenna |

FPC Link-Budget Mini-Calculator

Once you estimate losses, confirm your link margin before shipment. This tool approximates whether your FPC antenna design keeps enough headroom under realistic path loss.

Inputs

| Field | Variable | Typical Value | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| TX power | tx_power_dBm | 15 – 20 | module datasheet |

| Antenna gain | antenna_gain_dBi | 1 – 3 | from prototype test |

| Feeder loss | feeder_loss_dB | from A | cable + connector |

| RX sensitivity | rx_sensitivity_dBm | -92 to -96 | typical for Wi-Fi |

| Path loss | path_loss_dB | FSPL or measured | depends on distance |

Formulas

EIRP_dBm = tx_power_dBm − feeder_loss_dB + antenna_gain_dBi

link_margin_dB = EIRP_dBm − path_loss_dB − rx_sensitivity_dBm

Interpretation

| Link Margin | Meaning | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 10 dB | Excellent | Freeze design |

| 6 – 10 dB | Acceptable | Validate with OTA |

| < 6 dB | Weak | Upgrade cable / reduce connectors / enlarge window |

Example:

If TX = 18 dBm, gain = 2 dBi, feeder = 0.8 dB, RX = –94 dBm, path = 100 dB to link_margin = (18 – 0.8 + 2 – 100 + 94) = 13.2 dB Safe margin.

This simple math, similar to what TEJTE includes in its RF Cable Loss Estimator, keeps teams aligned before committing tooling.

FAQ — FPC Antenna

Below are real-world questions engineers often ask during layout and verification.

All answers reflect field experience and validated TEJTE design data.

1. How much metal clearance is “safe” around a 2.4 GHz FPC before detuning dominates?

2. What’s the practical max length for 0.81 mm vs 1.13 mm pigtails before loss hurts link margin?

3. Can a small plastic window in a metal case fully restore FPC efficiency?

4. When should I switch from an internal FPC to an external rubber-duck antenna?

5. How do I place two FPCs for MIMO without coupling?

6. Which quick VNA or OTA checks prove tuning before DVT sign-off?

7. Do I need separate keep-outs for 2.4/5/6 GHz, or can one window serve all?

Final Note

This graphic visually summarizes the core thesis of the entire document: successful FPC antenna design relies on adhering to a few key numerical rules (e.g., 15 mm from metal, 5x thickness bend radius, <0.3 m jumper). It emphasizes that the design mindset of treating the antenna as an active core component rather than an afterthought “sticker” is key to ensuring stable wireless performance even inside demanding enclosures.

Designing with FPC antennas is a balancing act — between mechanical limits and invisible electromagnetic behavior. Respect a few numbers (15 mm from metal, 5× bend radius, < 0.3 m pigtail), and you’ll likely pass on the first try. Ignore them, and no amount of matching pads will save the link.

Engineers who treat the antenna not as “just a sticker” but as an active component achieve stable Wi-Fi performance even inside the toughest housings. That mindset, combined with the structured tools above, defines why so many teams now treat the FPC antenna as a core part of their RF design — not an afterthought.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.