Rubber Ducky Antenna Guide: Indoor Coverage & SMA Matching

Dec 17,2025

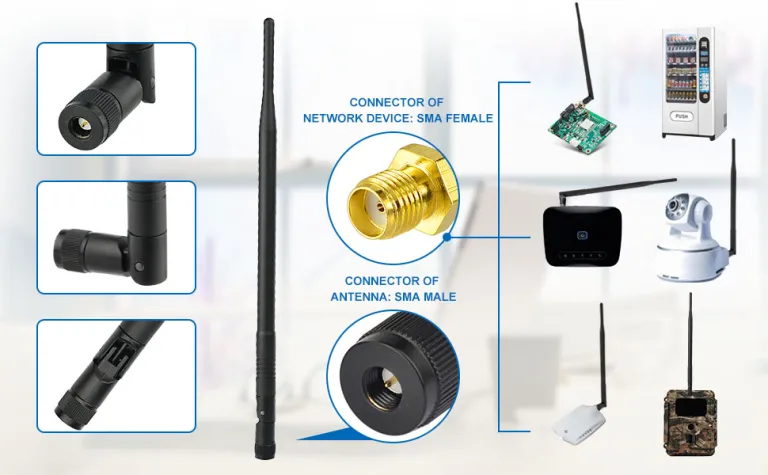

This diagram helps readers understand the connection between antenna selection and specific usage environments (e.g., space, device type), providing a visual reference for initial selection.

Which rubber ducky antenna form best fits your device and space?

This image visually compares the mechanical characteristics of different antenna forms and their advantages in solving specific installation challenges (e.g., avoiding metal, reducing connector stress).

Engineers like to joke that all rubber ducky antennas look the same—until one fails a range test. What seems like a simple plastic whip actually hides a complex balance of form, gain, and mechanical fit. The trick is not to pick the “highest dBi” but to match your enclosure, clearance, and signal path.

In small IoT hubs or handheld radios, a straight rubber-duck works fine if the space allows it to stand clear of metal and ground planes. But the moment you wall-mount your device or squeeze it near batteries, a right-angle version keeps the whip clear and prevents strain on the SMA base. A bendable type, with a flexible joint or coil, helps when you need to angle the field slightly—useful for crowded racks or gateways where vertical space is tight.

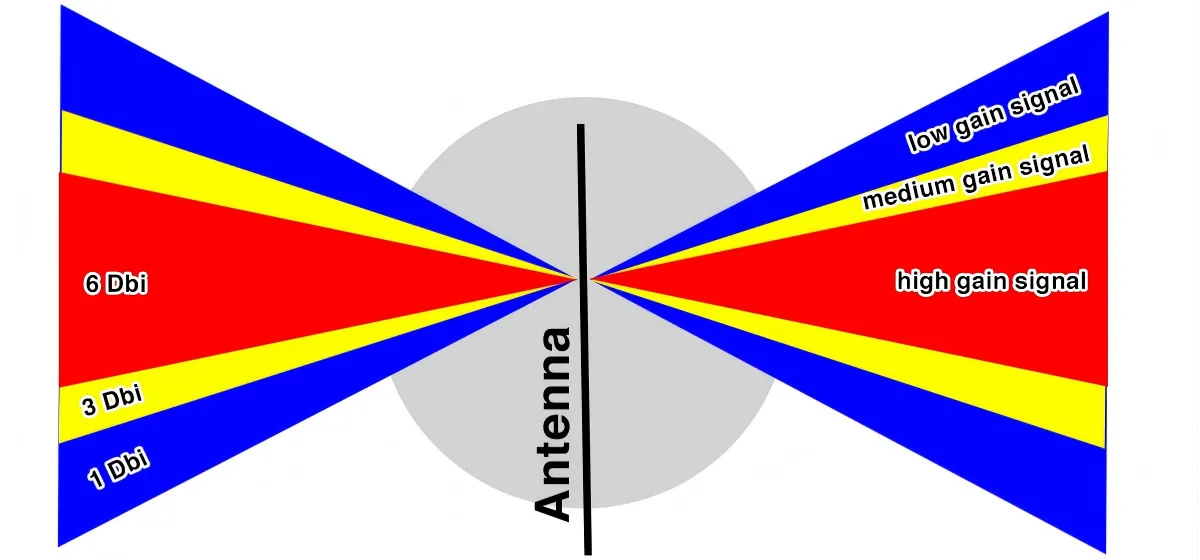

You’ll also want to size gain according to where your signal travels:

- 2 dBi: wide beam, perfect for short-range or multi-floor coverage.

- 3 dBi: balanced for most indoor routers or APs.

- 5–6 dBi: narrow beam, strong in hallways but may leave “dead cones” above or below.

This chart visually compares the radiation beam patterns and their effective coverage in real-world environments for three common gain values. It emphasizes that higher gain is not always better; the key is matching the antenna to the target coverage area: wide beams ensure uniform coverage in three-dimensional space, while narrow beams sacrifice vertical coverage for greater horizontal penetration.

Most teams I’ve worked with underestimate how much the case plastic detunes the antenna. A polycarbonate lid just 1 mm thick can shift resonance by 30–40 MHz, while a nearby ground trace can rob you of half a dB. It’s worth taping the antenna in place and walking a quick RSSI scan before locking your housing design.

If you’re torn between internal and external builds, remember that a rubber-ducky outside the enclosure almost always outperforms a compact FPC antenna buried inside. The external version simply breathes better—less metal, more air, cleaner pattern. For cross-type comparisons, TEJTE’s Wi-Fi Antenna Guide breaks down how gain, cable length, and mounting style interact in real products.

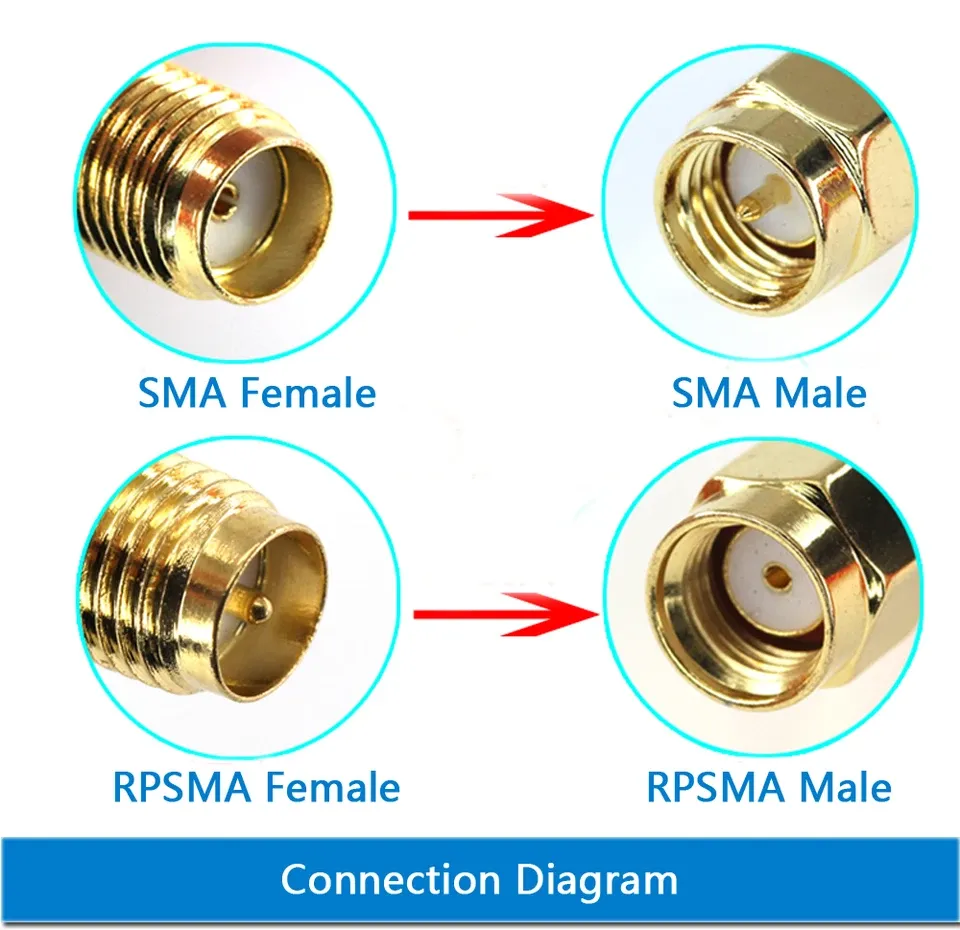

How do you tell SMA from RP-SMA in 5 seconds without tools?

The photo explains common SMA extension cable configurations: male-to-female for general use, male-to-male for specific setups, and RP-SMA for WiFi routers.

If you’ve ever scrambled on a lab bench swapping antennas, you know this pain—threads match, but the connector won’t mate. That’s the SMA vs RP-SMA trap. Fortunately, you can sort them out in seconds once you know what to look for.

Hold the connector to eye level:

- See a pin? That’s the male center.

- See a hole? That’s female.

Now check the threads:

- Outer threads = male shell.

- Inner threads = female shell.

Combine both clues and you’re done:

- Outer + pin to SMA-Male

- Outer + hole to RP-SMA-Male

- Inner + hole to SMA-Female

- Inner + pin to RP-SMA-Female

I’ve seen more than one project delayed simply because the procurement team mixed male/female or standard/reverse-polarity parts. A quick fix is color-coding: red shrink tube for RP types, blue for regular SMA. TEJTE’s cable assemblies now follow that convention to stop mismatched chains before they hit the line.

For those new to connector geometry, the SMA connector entry on Wikipedia shows clear cross-sections of the thread and pin layout. Bookmark it—it has saved many engineers from shipping the wrong batch.

When linking short pigtails—say, a 1.13 mm micro-coax to a bulkhead SMA—double-check gender consistency. A reversed segment can introduce 2 dB mismatch loss at 6 GHz, which is enough to skew test results. It sounds trivial, but anyone who has debugged phantom VSWR spikes knows this small oversight costs hours.

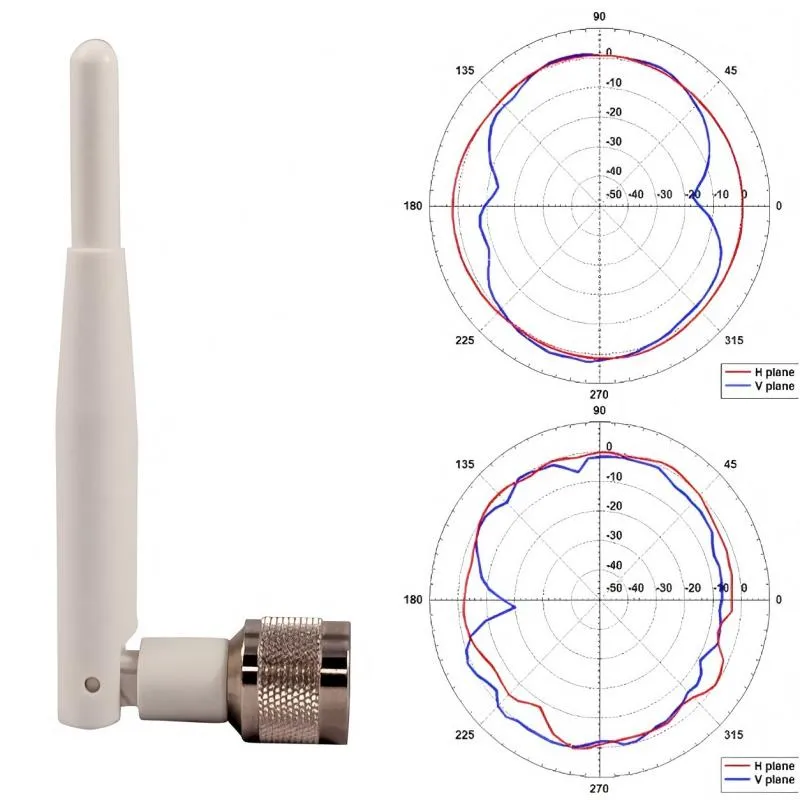

Will a 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi rubber-ducky meet your corridor coverage target?

This image explains how antenna gain selection directly affects effective coverage range and potential signal blind spots (e.g., elevation nulls) in long, narrow, and obstructed environments.

That depends on what you expect from “coverage.” In open corridors, even a 2 dBi rubber-duck antenna can hold a link across 20 meters. The trouble starts when the hallway twists or fills with metal racks. At that point, a higher-gain 5 dBi whip helps in one direction but may create blind spots vertically—a pattern known as the elevation null.

At 2.4 GHz, the longer wavelength tends to wrap around walls and furniture, giving reliable reach for IoT nodes. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, reflections dominate, and the beam narrows. So, while you gain data rate, you lose uniformity. That’s why installers often stay with 2.4 GHz for sensor networks and reserve 5 GHz for high-bandwidth APs.

Here’s a rough rule of thumb from field measurements:

| Band | Gain (dBi) | Line-of-Sight Range (m) | RSSI Drop per 10 m | Best Fit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | 2 – 3 | 25 – 30 | ~ 6 dB | IoT hubs / multi-floor |

| 5 GHz | 5 – 6 | 15 – 20 | ~ 9 dB | Wi-Fi 6 routers |

| 6 GHz | 5 – 6 | 10 – 15 | ≈ 12 dB | Lab tests / Wi-Fi 7 |

You’ll notice throughput doesn’t fall as fast as RSSI. Adaptive modulation keeps links usable even 10 dB down, though latency creeps up. That’s why engineers rely on real throughput tests, not just signal bars. In cluttered offices, reflections can actually help MIMO maintain data rates despite lower signal strength.

During prototype trials, tape the antenna on the intended spot—desk edge, wall plate, or enclosure top—and stream a continuous data test. Watch how throughput changes when you move five steps left or right; it reveals pattern gaps no analyzer graph will show.

For a deeper look at omni coverage behavior, see TEJTE’s Omnidirectional Wi-Fi Antenna Selection and Coverage Optimization.

What cable and adapter choices quietly erase your link margin?

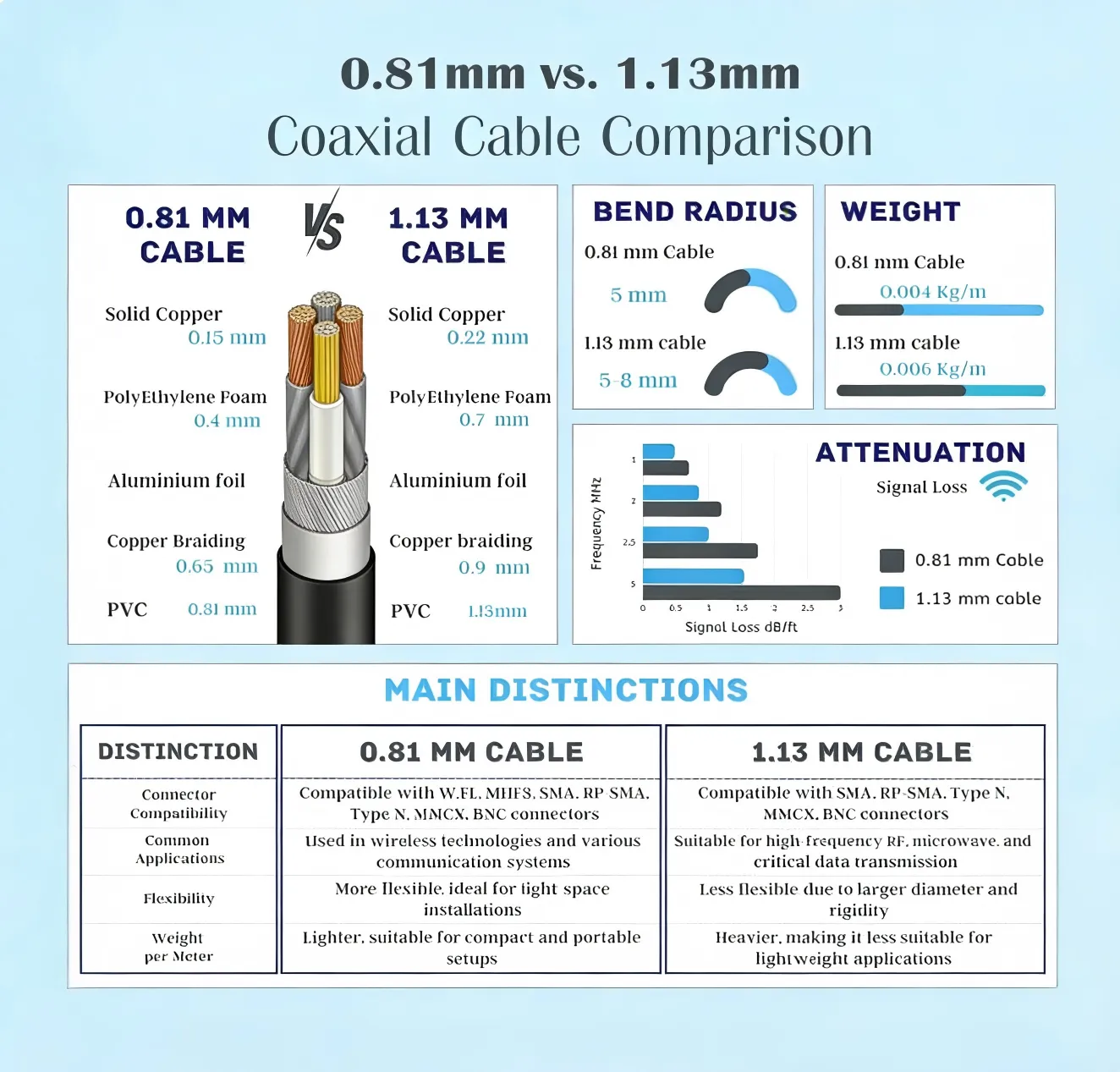

This image is part of the section discussing “Will feeder type and length silently erase your EIRP?”. It goes beyond simple loss figures to provide an extremely detailed engineering comparison. The chart not only visually displays the physical construction differences between the two commonly used micro-coax cables (e.g., conductor diameter, shielding thickness) but also systematically compares key parameters affecting actual installation and performance. This image provides comprehensive decision-making basis for engineers selecting feeder lines inside compact devices, especially when balancing flexibility, weight, connector compatibility against attenuation performance.

Every rubber ducky antenna starts with decent gain, but a poor feeder setup can quietly destroy that advantage before the signal even leaves the housing. Cable loss is the silent killer of indoor RF design.

Most compact Wi-Fi or IoT assemblies use thin micro-coax lines such as 0.81 mm or 1.13 mm. They’re flexible, easy to route, and cheap. The trade-off is attenuation: roughly 0.8 dB/m for 0.81 mm and 0.6 dB/m for 1.13 mm at 2.4 GHz. Stretch that to 30 cm, and you’ve already lost about a quarter-decibel.

By contrast, LMR-240 or LMR-400 cables are bulkier but far lower loss—around 0.26 dB/m and 0.14 dB/m respectively. In short indoor jumpers that doesn’t sound like much, but once you add several connectors, losses add up faster than most realize.

Here’s a quick comparison:

| Cable Type | OD (mm) | Loss @ 2.4 GHz (dB/m) | Flexibility | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.81 mm micro-coax | 0.81 | 0.80 | Very high | PCB to SMA bulkhead |

| 1.13 mm micro-coax | 1.13 | 0.60 | High | Internal routing |

| LMR-240 | 6.1 | 0.26 | Medium | External patch cables |

| LMR-400 | 10.3 | 0.14 | Low | Test bench / long runs |

Besides raw loss, connector pairs introduce mismatch and extra reflections. Each interface—male to female SMA, adapter, or bulkhead—adds about 0.15 dB insertion loss and a small VSWR bump. Two or three pairs can easily chew through 0.5 dB of your link margin.

When you evaluate feed lines, use a simple link-budget check rather than guesswork.

If the EIRP drops below receiver sensitivity by more than 6 dB, you’re on the edge—shorten the jumper or move to a thicker coax. Most teams chasing “better gain” could instead gain more by trimming one connector.

For design engineers who frequently swap antennas during validation, TEJTE’s RF Coaxial Cable Guide breaks down how feeder type and connector count affect overall link stability and return-loss margin.

Where should you place the rubber-ducky to avoid metal detuning?

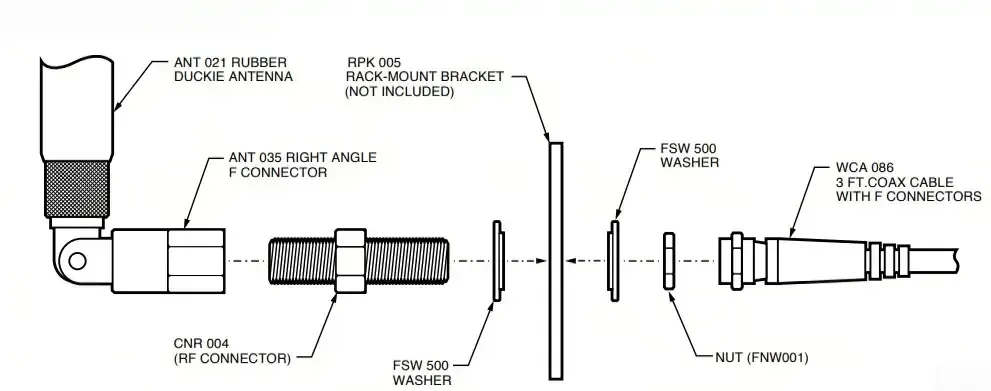

This exploded view details how to minimize the impact of metal components on antenna resonant frequency and radiation efficiency through rational spatial layout and isolation distance in device structural design.

Antenna placement is one of those quiet decisions that either makes a design shine—or ruins it no matter how perfect the schematic. Metal is the usual culprit. The closer a rubber-ducky antenna sits to grounded metal, the more its resonant frequency drifts, often by tens of megahertz.

The rule of thumb: keep at least one antenna diameter (typically 12–15 mm) of air gap from any conductive surface. Double that if it’s parallel to a heat-sink or battery pack. In my own projects, moving the antenna just 10 mm away from an aluminum bracket recovered nearly 1 dB of return-loss improvement.

If your enclosure has a large ground plane or shielding can, treat it as part of the system, not a bystander. The near-field coupling can either boost or cancel depending on orientation. A quick A/B test—antenna vertical vs horizontal—often reveals the cleaner configuration.

Also watch for cross-coupling between antennas. Two 2.4 GHz whips mounted less than 5 cm apart will almost certainly interact, raising the noise floor and hurting throughput. In multi-antenna devices, aim for at least a quarter-wavelength separation (≈ 31 mm @ 2.4 GHz). If space is tight, a slight tilt of 20–30° reduces correlation and keeps MIMO performance intact.

Finally, avoid stacking antennas near metal shields or ground pads inside the PCB zone. Even if you meet gain specs on paper, hand placement during operation can still detune the antenna by 3–5 dB. Quick trick: have a tester hold the device naturally, then walk a throughput test—if numbers drop drastically, that’s hand-detune in action.

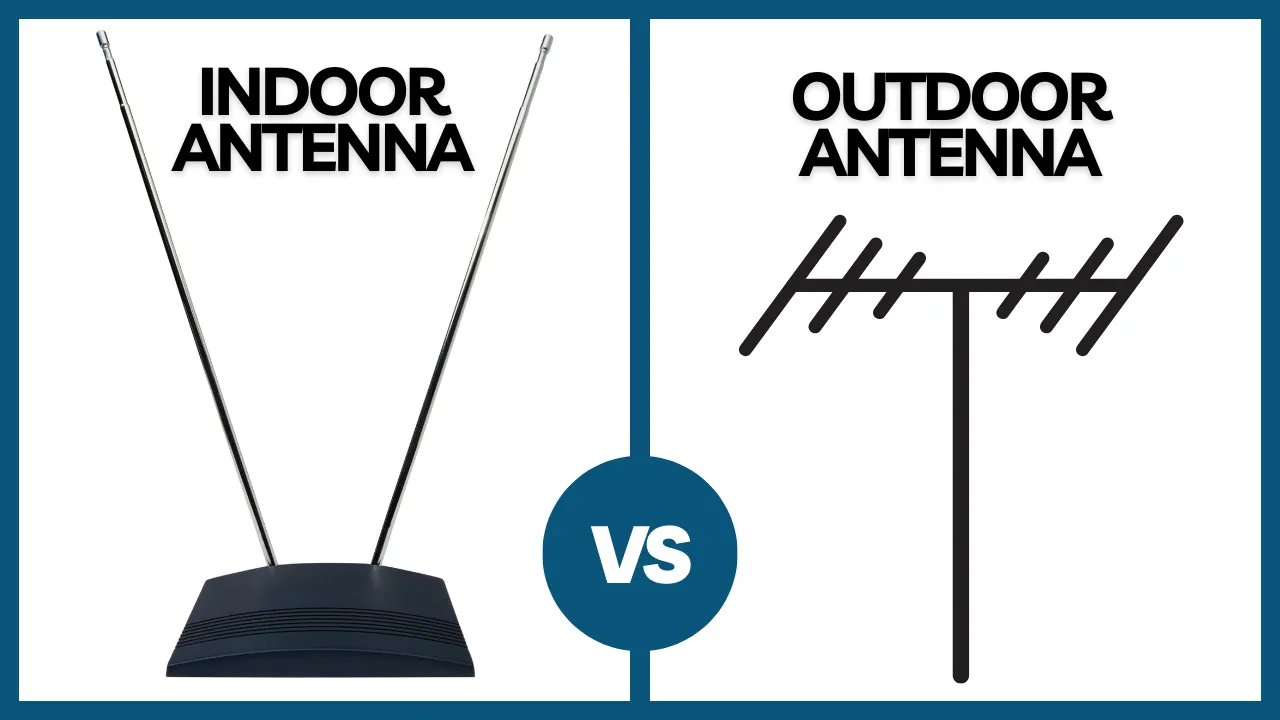

When should you move from a rubber-ducky to an outdoor omni?

This chart clearly delineates the application boundaries between rubber ducky antennas (for protected indoor environments) and outdoor omni antennas (for harsh outdoor environments), guiding users to make the correct choice based on deployment conditions.

There’s a limit to what a rubber-ducky antenna can handle. It’s designed for indoor or semi-protected spaces, not direct sunlight or constant humidity. Once your installation extends into hallways, patios, or warehouse docks, it’s time to consider an outdoor omni antenna.

Rubber-duckies are typically rated around IP30–IP40—fine for dust, not for rain. Outdoor units start at IP65 and climb to IP67, featuring O-ring seals, gaskets, and weather-proof boots. They also include reinforced SMA or N-type connectors capable of withstanding torque between 0.6 – 0.9 N·m, preventing micro-cracks during seasonal expansion.

Here’s a quick contrast snapshot:

| Feature | Rubber-Ducky (Indoor) | Outdoor Omni |

|---|---|---|

| IP Rating | IP30-40 | IP65-67 |

| Gain Range | 2-6 dBi | 3-9 dBi |

| Mount | Direct SMA / device mount | Bracket / mast mount |

| Cable Type | 0.81-1.13 mm pigtail | LMR-240 / 400 |

| Typical Use | Routers, gateways, handhelds | Corridors, rooftops, outdoor APs |

If you only need weather resistance near doorways or semi-outdoor corridors, you can bridge the gap using cold-shrink tubing or self-amalgamating tape around the connector joint. It’s a quick, low-cost seal that keeps moisture out of SMA threads.

Still, once you expect year-round exposure, the smart move is to shift to an IP67 outdoor omni with a mast bracket. The upfront cost is small compared to service calls after corrosion sets in.

For mounting torque specs and sealing practices, TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna: Selection, IP67 & Mounting Guide outlines clamp torque limits, UV-proof materials, and waterproofing methods proven in field deployments.

Can you validate placement fast before freezing the BOM?

You don’t need a full anechoic chamber to validate a rubber ducky antenna layout. In early prototypes, a few field-style tests can reveal 80% of the performance issues that would otherwise appear months later.

Start with A/B orientation tests. Rotate the antenna 90° or 180° relative to its default mounting. If your RSSI shifts more than 3 dB, the design is sensitive to polarization or nearby metal. For handheld devices, have multiple testers hold the unit naturally—some with their left hand, some right—and stream a continuous throughput test. Any repeatable dip over 20% likely means hand detuning or ground-coupling inside the case.

Next, perform a quick isolation test in three steps:

- Swap the antenna while keeping the same cable.

- Swap only the cable, keeping the antenna fixed.

- Swap both, then note where performance changes.

This “cable-first” method tells you exactly where loss or mismatch occurs without complex instruments. If replacing the cable alone recovers several dB, your feeder or connector is the culprit, not the antenna.

A small Wi-Fi throughput app or a simple iperf link is often enough for validation. Engineers sometimes overcomplicate this stage, chasing millivolts on VNAs while ignoring the real traffic experience. The point here is not lab precision—it’s repeatable confidence before locking your bill of materials (BOM).

How should you order so your PO is fool-proof?

This module diagram represents the “black-boxing” trend in modern RF design. It shows a module integrating the chip, matching circuit, and a standard antenna interface, emphasizing its pre-certified and fixed-layout characteristics. The diagram reminds engineers that while using such modules simplifies certification, the clearance and layout requirements in their reference design must be strictly adhered to and cannot be arbitrarily altered.

Once validation passes, ordering correctly becomes the next big hurdle. Many teams lose time not because of manufacturing errors, but because the purchase order (PO) lacks key specification fields. A solid PO ensures what arrives matches exactly what passed your test.

Below is the Rubber-Ducky Antenna Ordering & Compatibility Matrix, built from real TEJTE manufacturing data. It doubles as your checklist before submitting any order.

| Spec Field | Example / Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gain & Length | 2 / 3 / 5 / 6 dBi; 5-20 cm | Match to coverage profile |

| Connector | SMA / RP-SMA; Straight / Right-angle | Confirm gender & polarity |

| Color | Black / White | Optional visual code |

| Cable | 0.81 / 1.13 / LMR-240 / 400; 0.1-1.5 m | Verify length vs loss |

| Mount | Device / Panel / Bulkhead | Match mechanical fit |

| Label | Gender / Angle / Gain | Prevent mix-ups |

| Compliance | RoHS / REACH | Always required for export |

| Torque | 0.6-0.9 N·m | For SMA tightening |

| Temperature | -40 °C to +85 °C | Check operating range |

| Packaging | Individual polybag / bulk | For assembly line use |

| TEJTE SKU | e.g. RDA-SMA-03R | Internal traceability |

| Lead Time | 7-15 days | May vary by batch |

| MOQ | 50 pcs typical | Confirm before quotation |

| RMA Mark | Printed label on bag | For quality traceability |

Mini Link-Budget Calculator

Use this to confirm your configuration before ordering production batches.

Inputs:

tx_power_dBm, antenna_gain_dBi, feeder_type, feeder_length_m, connector_pairs, freq_GHz, rx_sensitivity_dBm, path_loss_dB

Reference Loss @2.4 GHz:

- 0.81 mm ≈ 0.8 dB/m

- 1.13 mm ≈ 0.6 dB/m

- LMR-240 ≈ 0.26 dB/m

- LMR-400 ≈ 0.14 dB/m

- Connector ≈ 0.15 dB per pair

Formulas:

feeder_loss = loss_per_m × feeder_length_m

conn_loss = connector_pairs × 0.15

EIRP = tx_power_dBm – feeder_loss – conn_loss + antenna_gain_dBi

link_margin = EIRP – path_loss_dB – rx_sensitivity_dBm

Decision Rule:

If link_margin < 6 dB, shorten the pigtail, reduce connector pairs, use thicker coax, or raise antenna gain slightly.

This simple spreadsheet test has saved more engineers from “mystery short range” than any simulation tool. TEJTE keeps this logic built into its internal ordering form to verify each SKU configuration before confirming production.

What changed in 2024–2025 for indoor omni choices?

The indoor RF scene evolved quickly in the last two years. Tri-band routers (2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz) became mainstream, and industrial IoT gear started keeping 2.4 GHz for reliability even while adding 6 GHz for bandwidth. That means the rubber ducky antenna didn’t disappear—it simply shifted roles.

Today, compact omnidirectional whips remain crucial for gateway side links, test kits, and service tools. Manufacturers like TEJTE standardized several gain/angle combinations into pre-certified SKUs, letting field teams swap replacements without new validation each time. This also shortened RMA turnaround: instead of “find an equivalent,” the label itself tells you the exact mechanical and RF match.

If you’re managing fleets of Wi-Fi or LoRa gateways, consider keeping a replacement kit with 2 dBi and 5 dBi variants. The kit approach reduces downtime and ensures compatibility across mixed enclosures—especially where units cross between indoor corridors and semi-outdoor walls. It’s small workflow improvements like this that keep maintenance predictable and prevent RF guesswork later.

FAQ — Rubber Ducky Antenna

How should you order so the PO is buildable and weather-safe?

Q1. Does a 6 dBi rubber-ducky improve indoor coverage or create elevation dead zones?

Usually both. You’ll get stronger horizontal reach in hallways but may lose coverage above and below the antenna. For multi-floor or stairwell use, 3 dBi often balances better.

Q2. How can I confirm RP-SMA vs SMA on a live device without unscrewing it?

Look closely: if the center pin is inside the device port, that port is female, so you’ll need a male antenna. No need to remove threads—just visual inspection works.

Q3. What’s the longest micro-coax pigtail before loss dominates at 2.4 GHz?

About 30 cm for 1.13 mm coax. Beyond that, loss outweighs convenience. For longer runs, move up to LMR-240.

Q4. Where should I mount the antenna on a handheld to avoid detuning by the user’s hand?

Place it near the top edge, away from the main PCB ground and batteries. Even a 15 mm gap from metal makes a measurable difference.

Q5. When should I upgrade from a rubber-ducky to an outdoor omni?

As soon as the antenna faces constant humidity or sunlight. Indoor plastics degrade fast under UV. An IP67-rated omni with a bracket saves endless service calls.

Q6. Are rubber ducky antennas truly omnidirectional?

Mostly yes, but the real pattern is doughnut-shaped—strongest in the horizontal plane and weaker directly above or below.

Final Thoughts

This summary graphic visually emphasizes the cumulative impact of a series of "small choices"—from connectors and cables to placement—on overall "big performance," highlighting the importance of meticulous design.

The humble rubber ducky antenna remains a staple of wireless design because it balances performance, price, and simplicity. When engineers understand how small choices—connector gender, cable type, or placement—affect the signal chain, the difference in real-world range is dramatic.

Handled with the same care as any high-frequency component, this little whip delivers years of stable coverage, quietly doing the job that flashy directional panels often can’t.

For broader system context, explore TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna: Selection, IP67 & Mounting Guide to see how indoor whips transition to full-weatherproof assemblies.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.