SMA Pigtail: Length, Bend Rules & Routing Inside Enclosures

Nov 23,2025

Preface

Short internal coax runs look deceptively simple. Most engineers have seen a module connected to an SMA feedthrough with a tiny piece of RG316 cable and thought, “That should be fine.” But once you close the enclosure—especially a gasket-sealed AP, a LoRa gateway, or an industrial controller—the story can change. One bend too tight, a loop pressing into a hinge, or an unintended adapter chain can quietly raise insertion loss or shorten the connector’s mechanical life.

This article focuses only on what happens inside the box. Everything from pigtail length and bend radius to RG316 vs RG174 behavior and strain-relief choices affects your 900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, or 5 GHz performance. External chain design is another topic, but if you want background on the panel-mount side, the SMA feedthrough guide provides a solid foundation.

Introduction

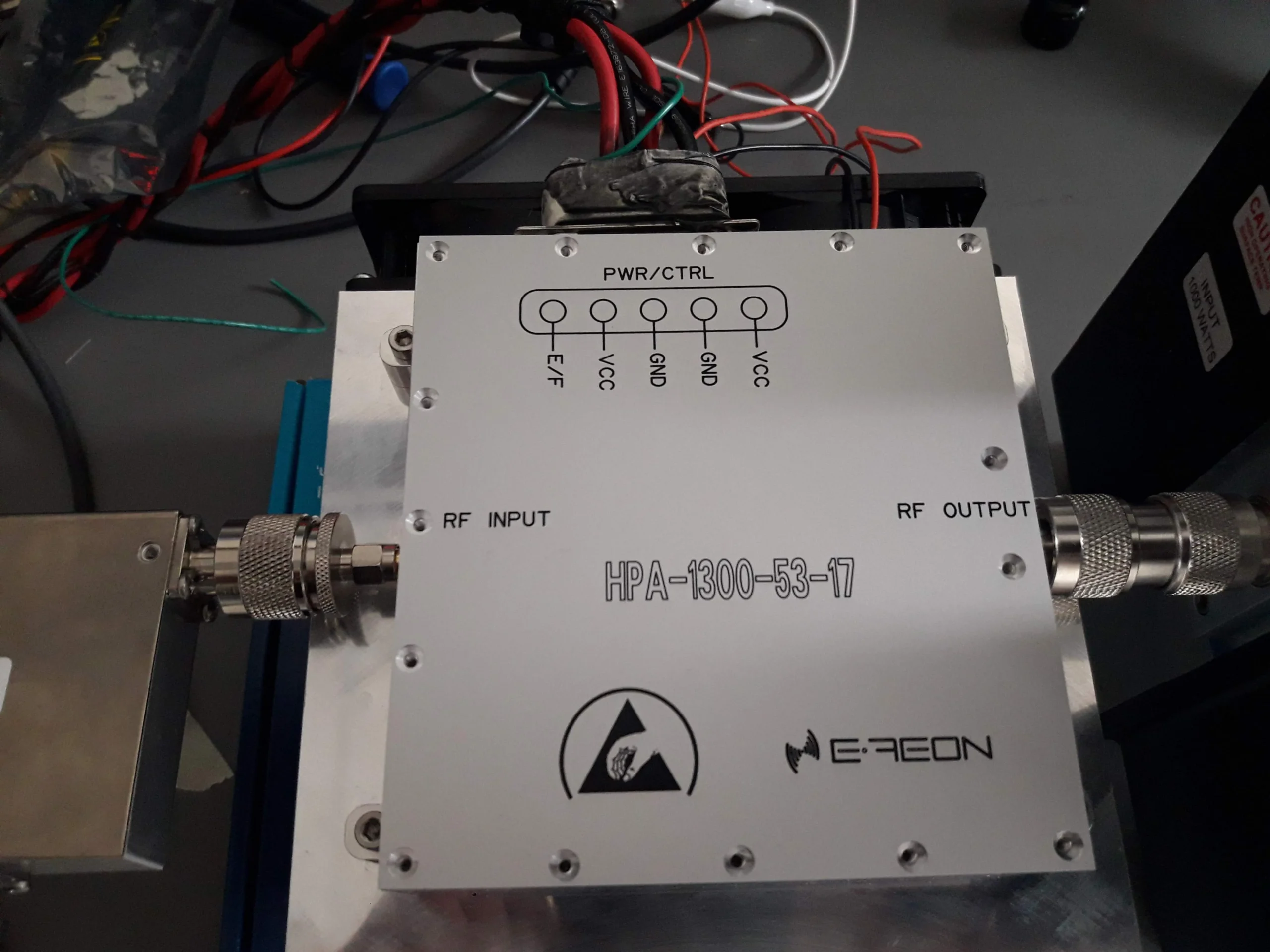

Figure is located in the introduction of the article. Its context emphasizes the importance of the SMA pigtail in internal enclosure routing. When done well, it's barely noticeable; when it isn't, problems like increased insertion loss or shortened mechanical life arise. This figure visually introduces the core issues to be discussed.

If you’ve ever opened a weather-sealed Wi-Fi enclosure or a compact monitoring node, you’ve probably paused at the sight of the SMA pigtail inside. It’s the one part you don’t think about until something feels off. When it’s done well—a short, smooth arc of RG316 leading from the module to the bulkhead—you barely notice it. When it isn’t, the problems tend to pop out immediately. A cable loop crushed against the lid, a boot bent at an odd angle, or a last-minute adapter someone added to fix a gender mismatch.

Those small missteps add up. A 5 GHz link can lose more than a decibel simply because the internal run is too long or forced into a sharp fold. In field installs, we’ve seen intermittent failures traced back to nothing more dramatic than a stressed boot that slowly degraded with temperature cycling. These aren’t edge cases—they’re common points of troubleshooting in labs and outdoor deployments.

Before diving deeper into direction mapping or material selection, it helps to establish a simple truth: inside a tight enclosure, the last 8–30 cm of coax matters as much as the antenna cable outside. If you need a broader reference on RG316’s electrical behavior, the RG316 coaxial cable guide offers the fundamentals. Here, we’ll stay strictly inside the box and look at the choices that influence link margin, serviceability, and long-term reliability.

How short should your SMA pigtail be inside the enclosure?

The context for Figure states that most compact enclosures behave best when the pigtail length falls between 0.08–0.30 m. Longer cables tend to collapse into S-curves, increasing loss and snagging risks. The context advises verifying the length by placing the pigtail in the actual enclosure and partially closing the lid, as CAD often misses real-world details.

Most compact enclosures behave best when the pigtail falls somewhere between 0.08–0.30 m. That range usually covers the distance from a PCB-mounted radio to the panel connector without forcing loops or excessive bends. A cable much longer than 30 cm tends to collapse into S-curves once the lid closes, even if the route looks fine when the enclosure is open.

Extra slack often feels like a “safe” choice in early prototypes, but it rarely ages well. A longer pigtail increases insertion loss and creates opportunities for the coax to snag on standoffs or hinge arms. If your build routinely needs more than 30 cm, it’s worth taking another look at the placement of the feedthrough or radio board. Clean builds typically avoid relying on mid-chain fixes like SMA extension jumpers or gender changers.

Every extra interface—whether intentional or improvised—adds both electrical and mechanical cost. At 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz, a small transition can introduce 0.05–0.20 dB of loss and a measurable VSWR bump. These numbers aren’t catastrophic by themselves, but compound quickly in systems with tight link margins.

Pick practical presets (0.08–0.3 m) without over-looping

Keep interfaces minimal: pigtail + feedthrough vs double adapters

What bend-radius and strain-relief rules prevent early failure?

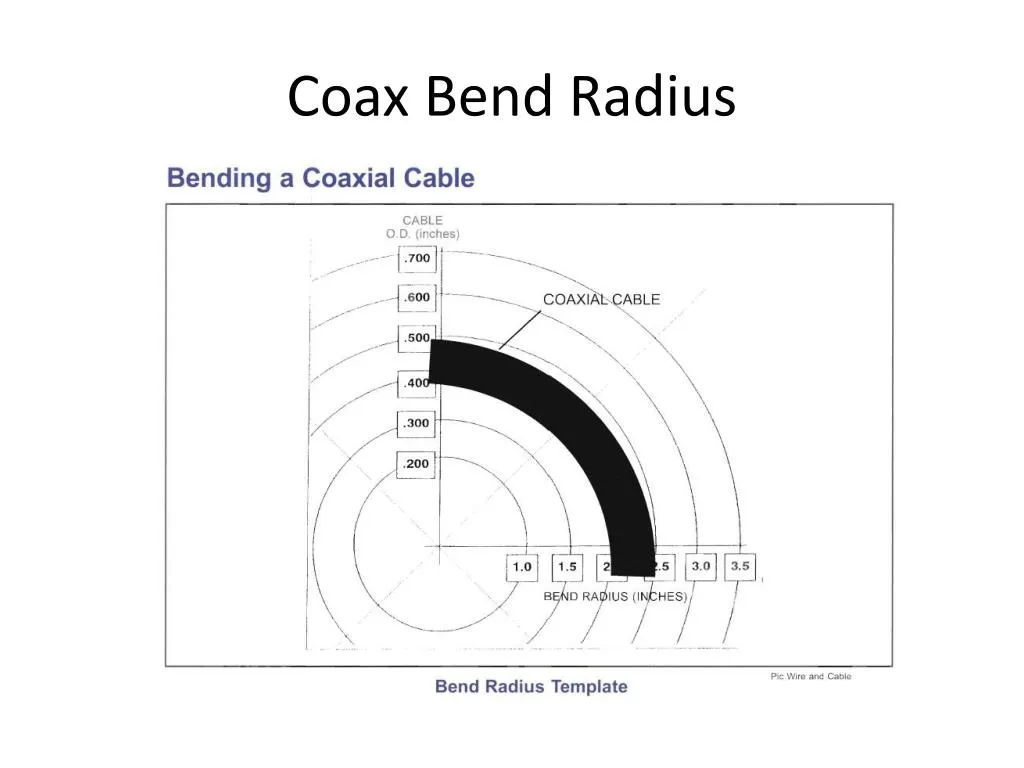

The context for Figure explains that coax often fails quietly right behind the connector boot, where strain is highest. Micro-cracks or braid stress can start here. A safe engineering rule is to keep the minimum bend radius ≈10× the cable's OD. Forcing a tighter bend near the boot dramatically shortens the assembly's life.

Coax doesn’t fail dramatically in most enclosures. It fails quietly—often right behind the connector boot. That region, the first 10–20 mm, carries the highest strain when the lid closes or when a technician opens the box for maintenance. Micro-cracks in the PTFE dielectric or stress on the braid can start here even when the rest of the cable looks untouched.

A safe engineering rule is to keep the minimum bend radius ≈ 10× the cable’s OD. With RG316 at roughly 2.5 mm OD, that gives a 25 mm radius. To many engineers, that radius feels surprisingly big once they try to route it inside a crowded box. But respecting it pays off in reliability. Forcing a tighter bend near the boot dramatically shortens the working life of the assembly—even more so in enclosures that open frequently.

Hinge-line routing is another common pitfall. Each open-close cycle nudges the coax, and over weeks or months, the cumulative movement leads to fatigue. Avoiding the hinge path entirely is ideal, but when space is tight, a right-angle SMA can redirect the stress away from the radio port or lid.

Minimum bend ≈ 10×OD near the boot; avoid hinge-line kinks

When a right-angle SMA reduces torque on instrument ports

The context corresponding to Figure states that right-angle connectors add a tiny VSWR change and loss, but inside tight enclosures, the mechanical advantage tends to outweigh the electrical cost. They redirect force away from the RF port, preserving both the port and the pigtail.

Can RG316 vs RG174 be swapped without breaking your loss budget?

The context for Figure 5 details the trade-offs: RG174 offers extreme flexibility but higher loss above 2 GHz and less shielding. RG316/RG316D provides more predictable RF performance, better shielding, and is preferred for higher frequencies, multi-radio devices, or noisy enclosures. The choice boils down to flexibility vs. predictable RF behavior.

Although both are 50-Ω families, their in-box behavior differs more than you might expect. RG174 bends easily and helps when routing space is severely limited. But its attenuation above 2 GHz rises quickly, and shielding performance lags behind RG316 and especially RG316D. For short internal lengths under 20 cm at sub-GHz bands, the difference may be small enough to tolerate. At 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, or GNSS, however, the divergence becomes significant even at modest lengths.

Internal EMI also plays a role. Enclosures with switching regulators, Ethernet PHYs, or MCU-dense layouts benefit from the stronger shielding of RG316D. Its slight rigidity is often a worthwhile trade-off for consistent performance and better immunity to desense.

Shielding, attenuation, flexibility trade-offs for short runs

RG174 shines where physical constraints dominate. RG316 is the more predictable option electrically, especially as frequency climbs. For many builds, the choice comes down to:tight path to RG174; predictable RF behavior to RG316.

Use RG316D (double shield) where EMI or handling is tougher

How do you map SMA male to SMA female directions correctly the first time?

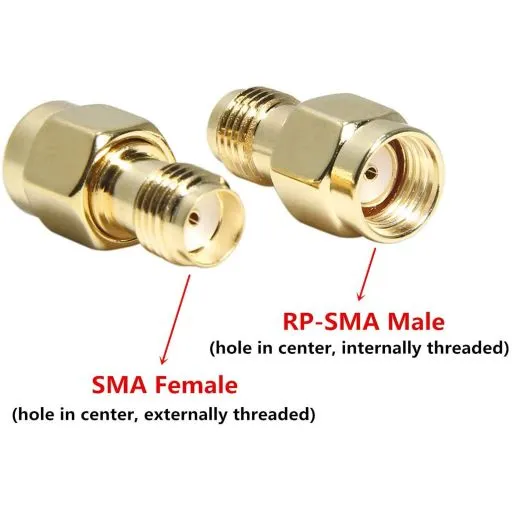

Connector direction errors inside enclosures are far more common than most teams admit. A board may expose an SMA female jack, while the technician expects a male, or the panel might use an SMA female bulkhead when an external antenna requires a male. Mix in RP-SMA hardware from Wi-Fi equipment, and the confusion compounds. The result? Someone adds a gender changer, and your clean chain suddenly gains an extra interface you never budgeted for.

The most reliable approach is surprisingly low-tech: label the chain from source to load and confirm the mechanical gender on both ends before the first prototype ships. Even experienced RF teams occasionally misread drawings when staring at top-down models. During reviews, call out not only “SMA M/F,” but also the pin vs. no-pin detail, since RP-SMA reverses the pin convention while keeping the thread pattern identical.

Color-coded heat-shrink boots or tiny laser-etched tags help during field swaps. We’ve seen installers accidentally plug a Wi-Fi 6E AP with an RP-SMA pigtail into a standard SMA bulkhead because both connectors looked “roughly correct” during a rooftop job. A few cents of marking would have avoided a 1 dB mismatch loss and a return visit.

When planning direction mapping, consider your feedthrough layout too. A well-placed bulkhead with the correct mating gender often prevents the need for extra adapters. If you want more background on feedthrough mechanics, the earlier-linked SMA feedthrough panel guide covers O-rings, seating, and torque behavior without forcing a second link here.

Label source to load; avoid SMA / RP-SMA mix-ups at APs

The context for Figure 6 emphasizes that RP-SMA is a major source of connector confusion. They look nearly identical but have reversed pin gender (RP-SMA male has a hole, SMA female has a hole, but threading is the same). This leads to mismates and RMAs. Using visual cues like colored boots or tags is recommended to prevent errors.

A quick checklist helps:

- Confirm thread type and pin gender for SMA vs RP-SMA

- Match connector gender at the radio and the panel

- Avoid “temporary” gender changers—they often become permanent

- Add visual cues (boots, tags, etched markers)

Small mistakes here typically cost far more time than they should.

Color-coded boots & tags for field swaps prevention

Do you need a bulkhead/feedthrough or direct pass-through at the wall?

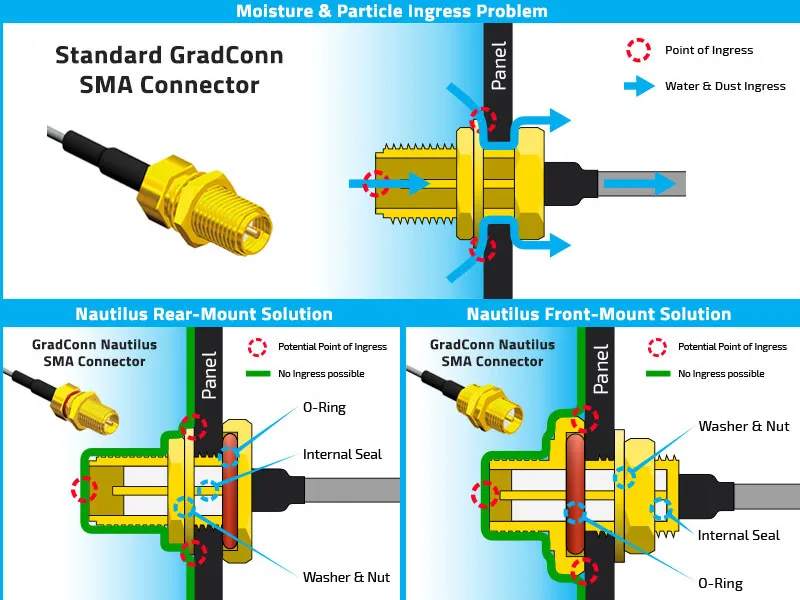

The context for Figure 7 discusses the choice between using a bulkhead feedthrough vs. a direct pass-through. A direct pass-through offers little strain relief and complicates sealing, while a proper bulkhead stabilizes the cable, provides grounding, and creates a maintainable interface. The figure highlights the importance of O-rings and internal seals for ingress protection.

Inside many enclosures, the decision between using a bulkhead SMA feedthrough or routing the pigtail directly through the wall determines how cleanly the assembly installs—and how long it lasts in the field. A direct pass-through sounds convenient, but it offers little strain relief and complicates sealing. In contrast, a proper bulkhead connector stabilizes the cable, provides a defined ground reference, and creates a replaceable maintenance interface.

Panel thickness matters more than most first-time designers realize. If the wall is thin, the nut and washer stack sits cleanly and the O-ring compresses as expected. Thicker walls, uneven cutouts, or painted surfaces change how the O-ring seats. Poor compression leads to moisture ingress or RF leakage paths. Ensuring the O-ring sits against bare metal—not paint—improves long-term environmental sealing.

A common pattern in outdoor APs uses an SMA pigtail inside and an N-type connector outside. The N-type handles weather exposure, torque, and antenna strain, while the internal SMA pigtail keeps the radio and feedthrough flexible. Designs mixing small internal coax and rugged external interfaces usually outperform single-cable pass-through attempts.

For broader mechanical considerations like washer stacks or torque limits, TEJTE’s feedthrough-focused content (linked earlier) offers deeper guidance without needing another explicit link here.

Panel thickness, washer stack, grounding path & O-ring seating

A bulkhead assembly only performs well when:

- The O-ring seats against unpainted, flat metal

- The panel thickness matches the connector spec

- The washer stack doesn’t tilt the connector

- Ground continuity is predictable

Ignoring these small details often introduces intermittent RF leakage or mechanical drift.

Pigtail inside + N-type outside: a common lab/rooftop pattern

How much insertion loss should you expect at 900 MHz / 2.4 GHz / 5 GHz?

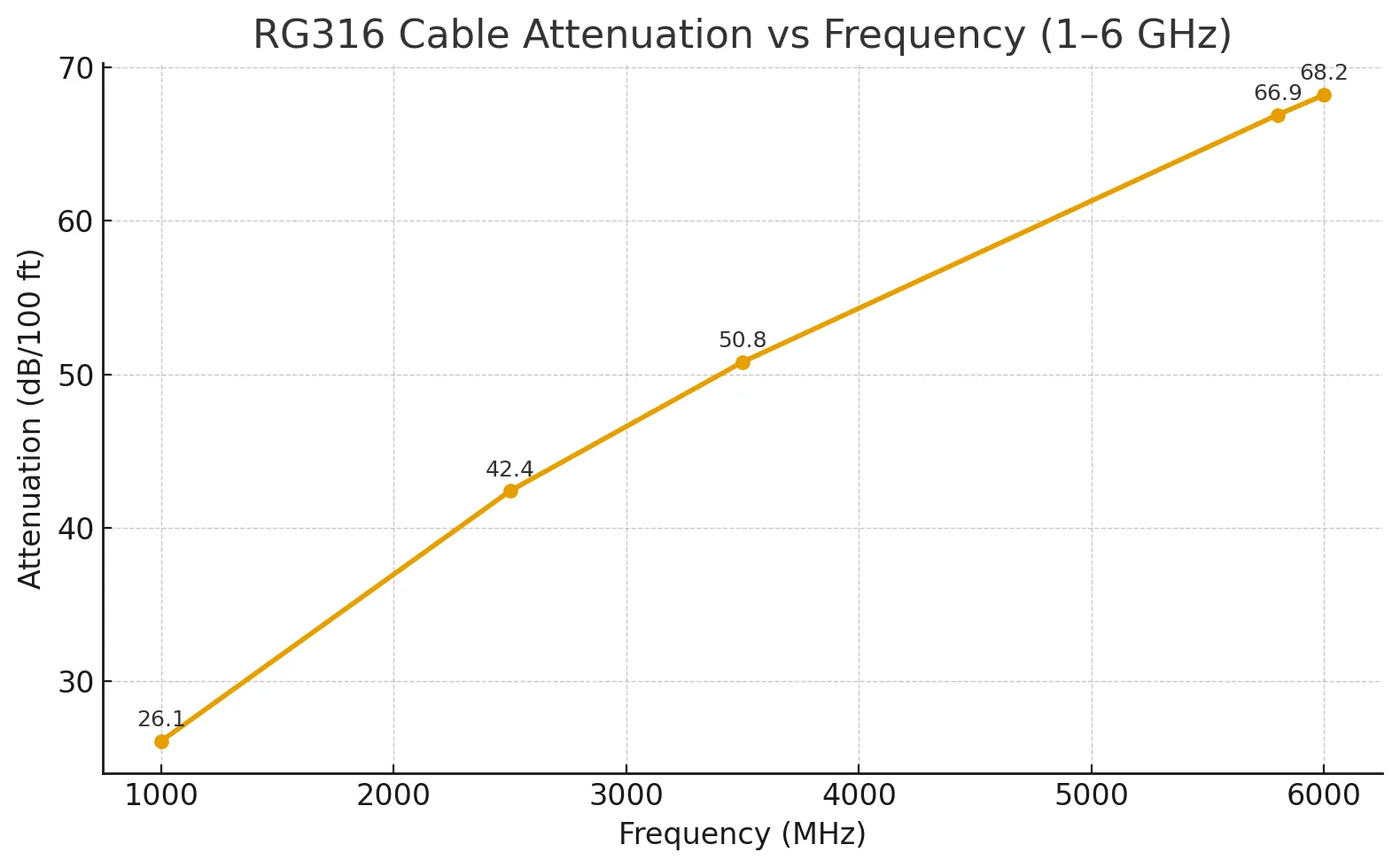

The context for Figure 8 states that even short pigtails are not immune to insertion loss concerns; higher frequencies make every centimeter count. Attenuation for typical RG316 assemblies can be estimated using per-meter values scaled to the short length. Excess length can nibble away link margin at 2.4/5 GHz. This graph provides the visual data needed for such estimations.

Short pigtails might seem immune to insertion loss concerns, but the higher the frequency, the more each centimeter counts. For typical RG316 assemblies, you can estimate attenuation using per-meter values and then apply the proportional reduction for your 0.1–0.3 m internal run. At 2.4 GHz, for example, even a small excess length can nibble away link margin—especially when combined with unnecessary adapters.

A simple estimate blends three contributors:

- Cable attenuation (frequency-dependent)

- Interface loss (0.05–0.20 dB per joint)

- Mismatch loss from imperfect VSWR

Because internal pigtails are short, mismatches at the terminations matter proportionally more than the cable itself. If your enclosure forces a tighter bend or multiple adapters, the effective IL rises faster than you might expect. A well-matched SMA chain with a clean arc often outperforms a longer but electrically “better” straight run.

If you need a refresher on how RG316 behaves across bands, the linked RG316 coax guide includes nominal attenuation tables that align with these calculations.

What recent RF news nudges pigtail length and sealing choices?

RF hardware decisions inside an enclosure don’t happen in a vacuum. Regulatory and standards updates over the past year have quietly shifted how engineers design enclosure routing, especially for Wi-Fi 6E/7 and emerging IoT infrastructure. These changes tighten expectations around sealing, pigtail length, and even bulkhead choices, particularly in outdoor or semi-outdoor deployments.

The FCC’s approval of additional 6 GHz Automated Frequency Coordination (AFC) operators—such as AXON Networks—effectively increases the number of standard-power APs entering the market. More standard-power devices mean more enclosures requiring short internal SMA pigtails and clean RF paths to maintain margin at higher EIRP levels. Installers already report that outdoor APs with long internal coax runs suffer noticeable desense when placed near hinge lines or thick panel corners.

A similar shift comes from the Wireless Broadband Alliance’s (WBA) commercial AFC activation. Enterprise deployments are expanding to rooftop and warehouse environments where environmental sealing matters more than before. This trend pushes designers to adopt tighter routing norms, often encouraging pigtails under 20 cm and high-quality PTFE jackets that hold up under thermal cycling.

Bluetooth’s newly published Bluetooth 6.0 specification also reshapes enclosure design. With stronger low-power links and more aggressive coexistence behavior, combo Wi-Fi/Bluetooth modules increasingly require short, well-shielded pigtails to prevent self-interference. Engineers have started choosing RG316D over RG174 in these scenarios—not because attenuation changes dramatically, but due to better immunity to desense and nearby digital noise.

And on the IoT side, the Wi-Fi Alliance’s expanded device certification efforts push integrators to clean up internal RF chains. In practice, this means fewer adapters, better-matched SMA gender mapping, and pigtails trimmed to the minimum length needed to hit the feedthrough.

FCC approves additional 6 GHz AFC operators to shorter internal pigtails & better sealing

WBA commercial AFC goes live to enterprise/industrial Wi-Fi expansions

Bluetooth 6.0 strengthens low-power links to more combo radios on panels

Wi-Fi Alliance promotes IoT certification rigor to cleaner 50-Ω chains

SMA Pigtail Inside-the-Box Planner

Figure is located in the "SMA Pigtail Inside-the-Box Planner" section, serving as an illustration of the typical application scenario that the planner is designed for. It visually represents the physical entities and connections corresponding to the planner's input parameters (e.g., frequency, cable type, length, interface count). The "RF Module -> Pigtail -> Feedthrough" chain depicted is the clean, minimal-linkage best practice advocated throughout the article, aiming for minimal loss, mechanical stress, and high reliability. This figure emphasizes the importance of detailed routing planning within a compact enclosure.

Inputs

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| frequency_MHz / GHz | Operating frequency |

| length_m | Pigtail length (0.08-0.30 m typical) |

| cable_type | RG316 / RG316D / RG174 |

| OD_mm | Cable outer diameter |

| min_bend_rule | Typically ×10 OD |

| interfaces_count | Number of transitions |

| IL_if_dB | Interface loss per joint (0.05-0.20 dB @ 1 GHz) |

| VSWR | Typically 1.15-1.30 for quality SMA |

| ambient_temp_°C | Internal enclosure temperature |

| loss_budget_dB | System-level limit |

| need_RA | Y/N (right-angle SMA requirement) |

| panel_offset_mm | Clearance from feedthrough to lid/hinge |

Engineering Formulas

1. Cable loss

cable_loss_dB=αdB/m(f)×length_m

2. Interface loss

ρ=VSWR+1VSWR−1mismatch_loss_dB=−10log10(1−ρ2)\text{mismatch\_loss\_dB}=-10\log_{10}(1-\rho^2)mismatch_loss_dB=−10log10(1−ρ2)

4. Total insertion loss

IL_total_dB=cable_loss_dB+interface_loss_dB+mismat

5. Bend clearance check

Rmin≥OD_mm×min_bend_rule

6. Hinge/panel clearance

panel_offset_mm≥Rmin+5 mm

Outputs

| Output | Meaning |

|---|---|

| cable_loss_dB | Loss from the cable itself |

| interface_loss_dB | Total penalty from connectors/adapters |

| mismatch_loss_dB | VSWR mismatch loss |

| IL_total_dB | Combined insertion loss |

| BendCheck | PASS / FAIL |

| HingeClearance | PASS / FAIL |

| Action | shorter / use RA / reduce interfaces / upgrade to RG316D |

FAQs

1 How far can I run an SMA pigtail from the feedthrough to my module?

2 What’s the clean way to connect an SMA RF cable to a wireless access point inside a box?

3 Any pitfalls when crimping an (RP-)SMA connector onto a short pigtail?

4 Which cable families pair best with SMA pigtails?

5 Is a right-angle SMA worse than a straight plug?

6 Do I need a bulkhead or can I pass the pigtail directly through the wall?

7 Will Bluetooth/Wi-Fi coexistence affect my pigtail choice?

Practical Engineering Notes

Engineers often underestimate how much the internal RF chain shapes final wireless performance. A pigtail that’s a few centimeters too long, a mismatched SMA gender, or a bend sitting too close to the hinge may not fail immediately—but these small issues collectively erode link budget, raise VSWR, and reduce the device’s tolerance to temperature swings.

Short, well-planned SMA pigtails—paired with the correct feedthrough and cable family—carry more impact than most RF teams assume. Choosing RG316 or RG316D, managing bends responsibly, and minimizing interface count keeps the internal path consistent no matter how aggressively the external environment pushes back.

As Wi-Fi 7, Bluetooth 6.0, and AFC-enabled 6 GHz systems become more common, these internal details matter even more. Getting them right avoids field failures, reduces service costs, and improves RF repeatability across production runs.

Final Notes

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.