SMA Feedthrough: Panel Mount & IP Tips

Nov 22,2025

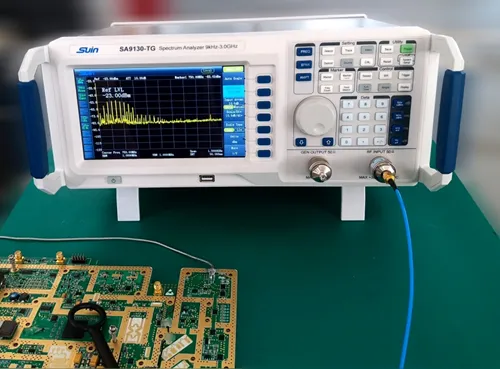

Figure vividly depicts a critical maintenance aspect for SMA feedthroughs in practical applications - inspection. Its context points out that even a well-installed connector can become vulnerable due to thermal cycles, cabinet shifts, or oxidation. Maintenance techs often include quick inspection steps: confirming dust caps seat fully, checking torque after thermal cycles, cleaning oxidation around the feedthrough shoulder, and re-seating boots if the cabinet has shifted. This figure serves as a visual reminder that consistent inspection is an effective measure against long-term performance degradation caused by subtle moisture intrusion or mechanical stress.

Many engineers look at an SMA feedthrough as a simple pass-through—until they start mounting hardware inside a cramped cabinet or a weather-sealed box. At that point, small details begin to matter: thread length, the way a nut bites into the panel coating, or how an extra interface shifts a 5 GHz link budget. Field technicians see this a lot. A feedthrough looks trivial, but the wrong gender or orientation often forces them to add adapters, and that’s usually when loss and mechanical stress start creeping in.

This guide follows the real workflow you’d encounter on the bench: map direction first, sort out bulkhead vs pass-through bodies, then evaluate sealing windows, stress, cable families, and ordering notes. I’ll reference relevant TEJTE guides—like their SMA connector overview, RG316 coax notes, and SMA extension routing tips—only where they naturally clarify a point.

How do you choose the right SMA feedthrough for your panel?

The first—and oddly the most overlooked—step is deciding the gender and direction on each side of the panel. Plenty of integration issues come from assuming what the external side “should” be. That’s how teams end up with two male sides and a last-minute hunt for an adapter. An adapter works, of course, but each one adds loss, length, and more places for torque stress.

Engineers who routinely work with access points, GNSS receivers, or test modules often form a habit: draw a quick inside-to-outside line and assign the connector bodies before cutting anything. It sounds simple, but it prevents weeks of avoidable revisions. For reference, TEJTE’s SMA connector guide breaks down gender behaviors in a way that matches what you’d see on test benches.

Map port direction & gender (SMA-M/F to inside/outside) before drilling

Figure visually illustrates the three key points that need to be planned for a clean SMA chain: the internal device port, external equipment, and field service considerations. Its context strongly advises completing this mapping before drilling, stating that ten seconds of planning can save hours of corrections.

A clean SMA chain starts with mapping these three points:

- Internal device port — Some boards leave only enough depth for a low-profile male.

- External equipment — Many antennas expect SMA-F, while some Wi-Fi devices use RP variants.

- Field service — If an installer replaces the outer jumper during maintenance, a female outside makes capping easier.

When space is tight, placing SMA-M on the inside often helps the jumper exit more cleanly—especially with RG316 pigtails. When the enclosure is outdoors, a female on the outside is easier to seal because standard dust caps and boots seat consistently.

Good installers rarely drill before doing this mapping. It’s ten seconds of planning that saves hours of corrections.

Avoid RP-SMA mix-ups: labeling habits that prevent RMAs

RP-SMA is the number-one source of connector confusion in wireless builds. The bodies look nearly identical except for who holds the pin, and if someone grabs “SMA” from inventory without double-checking, the chain won’t mate. That leads to RMAs even though the underlying RF is perfectly fine.

What prevents those headaches are boring, repeatable habits:

- Add small gender + orientation labels on the panel during assembly.

- Use colored caps for chains like GPS vs Wi-Fi.

- Include full orientation codes in internal part numbers.

TEJTE’s teams who handle field radio chains have noted the same pattern in their SMA extension cable projects—RP variants cause issues only when labeling is skipped.

Do you need a bulkhead or a pass-through configuration?

The context corresponding to Figure explains the application scenarios for the Bulkhead connector: when panel thickness varies, compression of an O-ring or EMI gasket is needed, the connector might be torqued repeatedly, or matching existing cutouts in older equipment. It provides tuning space, allowing modification of washer stacks or addition of gaskets without redesigning the panel.

When bulkhead with nut/washer is safer than pass-through

A threaded bulkhead body is usually the right pick when:

- panel thickness varies between cabinet revisions,

- you need to compress an O-ring or EMI gasket,

- the connector could be torqued repeatedly,

- you’re matching existing cutouts in older equipment.

Bulkheads provide tuning space. You can modify washer stacks, add gaskets, or shift the compression window without redesigning the panel. This adjustability is why they’re common in telecom cabinets and test instruments. They also tend to offer better control of thread engagement—something TEJTE engineers often highlight when discussing RG316 coax assemblies and how strain interacts with the feedthrough.

Pass-through bodies, meanwhile, shine in compact enclosures where every millimeter counts. Their shoulder determines the seating depth, which keeps things neat but leaves no slack for sealing adjustments.

Grounding path and EMI gasket placement at the panel cutout

The feedthrough usually becomes part of the chassis ground path, and the consistency of that path affects return-loss behavior. A few practical rules hold true across most RF builds:

- Direct metal-to-metal contact at the shoulder gives a cleaner ground reference.

- Star washers help when the panel has paint or anodizing.

- EMI gaskets belong at the cutout, not loosely stacked under the nut.

- Shorter grounding paths reduce coupling when multiple radios share the same plate.

These same observations appear across TEJTE’s coax routing articles, particularly when discussing noise coupling near feedthroughs and cabinet edges.

What panel thickness and thread engagement guarantee a secure mount?

A secure SMA feedthrough isn’t just about tightening a nut until it “feels good.” The connector, the panel, the washer stack, and the O-ring all interact like parts of a small mechanical system. If any one element sits out of proportion—maybe the panel coating is thicker than expected, or the O-ring has a slightly different cross-section—the entire assembly shifts. Engineers often notice this later through inconsistent torque readings or small, annoying variations in return loss.

To keep the mount stable, most technicians rely on a simple idea: the nut needs enough thread to grab onto, but not so much that it bottoms out before compression happens. When a feedthrough behaves inconsistently in the field, the culprit is almost always found in the “stack-up”—the combined thickness of the metal panel, paint, washers, and elastomer. Minor deviations have real effects, especially in sealed cabinets.

In TEJTE’s manufacturing notes for RG316 coax assemblies, this interaction between mechanical load and connector geometry appears frequently, reinforcing how mechanical fit influences RF repeatability.

Stack-up math for nut + washer + panel + O-ring

Instead of treating the feedthrough like a single part, it’s more accurate to think of it as a layered system. The connector’s thread length provides a “budget,” and every layer of the assembly consumes part of that budget.

In practical engineering terms:

- You begin with the total usable thread length on the SMA barrel.

- From that, subtract the panel’s actual thickness (not what the CAD file says—measure a few samples).

- Subtract the combined washer height, depending on whether you need EMI bonding or additional mechanical bite.

What remains is your effective engagement length—the amount of thread actually available for the nut to clamp onto. Most technicians aim for a minimum engagement equal to roughly 80% of the nut’s internal height, as this level of contact tends to survive torque cycles without loosening.

The O-ring also has its own requirement: its cross-section needs to be compressed within a predictable range. Most sealing-grade elastomers behave best when squeezed somewhere around 15% to 25%. Below that range, gaps remain; above it, the O-ring may distort, roll, or fatigue prematurely.

A feedthrough that fails IP tests usually fails here, not because the connector is poor but because the stack-up didn’t place the O-ring in its intended compression zone.

Clearance for boots, caps, and RA plugs in tight cabinets

Engineers often discover too late that the right angle sma cable they planned to use doesn’t clear the door, latch, or internal wall. Any cap, dust boot, or RA plug requires extra room around the feedthrough—not just for installation, but for the geometry the jumper takes as it moves when the cabinet is closed.

For RG316 cable, try to maintain a bend radius roughly ten times the cable diameter near the connector. The cable won’t break instantly if bent tighter, but its impedance consistency will wander. In field cabinets, that variance shows up as small but repeatable shifts in return loss—especially when the door is opened and closed repeatedly, bending the jumper in slightly different ways each time.

When space is tight, some engineers flip the usual arrangement and place a straight SMA on the interior while routing a right-angle plug on the jumper. The connector stays predictable, and the harness gains room to breathe.

How do you hit the IP target (IP54/65/67) on outdoor installs?

Getting to IP54, IP65, or IP67 isn’t a matter of “add an O-ring and hope.” Outdoor cabinets face water that wicks sideways, dust that migrates into microscopic gaps, and temperature cycles that expand and contract the housing. A feedthrough has to survive all of that while keeping both the RF path and the mechanical joint stable.

In the field, installers quickly learn that sealing is holistic. The O-ring, the shoulder of the feedthrough, the panel finish, and even the torque applied to the external jumper all influence long-term performance. Many failures that look electrical at first glance trace back to moisture sneaking in during a freeze-thaw cycle months earlier.

Let’s break down what matters most in outdoor work.

O-ring seating, compression window, dust caps, strain relief

An O-ring performs well only when the surface it seals against is predictable. The panel needs to be flat, the O-ring needs to sit cleanly on its seat, and torque should be applied in controlled increments. Too much torque deforms the O-ring; too little leaves voids that become dust paths.

Common practices across outdoor radio and AP deployments include:

- keeping O-ring compression near 15–25%,

- positioning washer stacks away from the sealing plane,

- ensuring the O-ring touches bare metal or a stable finish,

- capping SMA-F ports when unmated,

If the external jumper uses heavier coax (like LMR-200), strain relief becomes even more critical. Large cables exert leverage that slowly pries the connector against its seal—long before the RF path shows trouble.

Mated vs unmated protection: service and inspection schedule

Even a well-installed sma bulkhead cable becomes vulnerable when the external side sits unmated for long periods. Moisture doesn’t need permission; it creeps through the tiniest imperfections, especially in coastal areas or industrial sites with condensation cycles.

Maintenance techs often include a quick inspection step:

- confirming dust caps seat fully,

- checking torque after thermal cycles,

- cleaning oxidation around the feedthrough shoulder,

- re-seating boots if the cabinet has shifted with temperature changes.

Even IP67 hardware benefits from consistent capping. It’s cheap insurance against the slow, silent intrusion of moisture.

Will a right-angle vs straight choice reduce strain without hurting RF?

Right-angle SMA connectors carry a strange reputation: some engineers expect them to ruin insertion loss, while others rely on them everywhere. In practice, the electrical difference between straight and RA bodies is small in the sub-6-GHz world. The mechanical difference, however, can be enormous.

Jumpers don’t just sit still. Every time a door swings shut or a radio pivots for service, the cable flexes. If the bend happens too close to the feedthrough—especially with thin coax like rg316 cable—the chain becomes sensitive to mechanical movement. An RA plug or RA feedthrough often gives the jumper a more natural sweep, preventing repeated micro-bends that slowly shift return-loss behavior.

This aligns with many field observations TEJTE engineers document when discussing SMA extension cable routing: interface count and cable strain usually matter more to reliability than the small electrical variation introduced by the RA geometry.

Where RA bodies improve reliability near doors/lids

Right-angle hardware shines whenever a straight connector would force the jumper into an immediate bend. Cabinet hinges, stiff harnesses, and close wall clearances make straight connectors inconvenient and sometimes risky.

RA bodies help when:

- the cable must turn immediately after passing the feedthrough,

- internal walls limit routing space,

- vibration pushes the cable toward sharp bends,

- the cabinet door closes tightly over internal wiring.

Instead of forcing the cable to comply with the enclosure, the RA shape reduces unnecessary stress and stabilizes long-term RF performance.

Keep interface count low: jumper vs double-adapter tradeoff

Many routing problems get fixed with two quick adapters—male-to-female, straight-to-RA, then back again. It works short-term but creates a long-term penalty: you introduce multiple interfaces, and each one adds insertion loss.

A cleaner approach is to:

- select a single RA plug,

- shorten the sma extension cable,

- or choose an RA feedthrough if the panel permits.

Single-piece geometry nearly always beats multi-adapter chains. Even small losses (0.05–0.20 dB per interface at 1 GHz) accumulate quickly when you multiply them across several joints.

What cable family and bend rules pair best with feedthroughs?

Picking the right cable family is one of those decisions that doesn’t seem important until the enclosure door refuses to close or the jumper starts drifting a few tenths of a dB over temperature. The sma feedthrough is only as reliable as the cable you mate to it. Most compact radios and test boxes lean toward RG316 cable or RG316D because they tolerate tighter bends, handle vibration decently, and offer predictable loss. Meanwhile, RG174 remains popular when extreme flexibility matters more than attenuation.

For short internal runs—especially the “device PCB to feedthrough” link—the sweet spot is usually a SMA pigtail built from RG316. It bends cleanly without kinking, and it doesn’t punish the return-loss budget the way some thinner miniature cables do. When the jumper gets longer or exits the cabinet into harsher environments, engineers shift to lower-loss classes, but inside the cabinet, flexibility usually wins.

TEJTE’s broader coax articles, particularly their RG316 vs RG174 comparison, reinforce the same theme: don’t over-optimize for loss if it forces a cable to run at the edge of its bend limit every time someone closes the door.

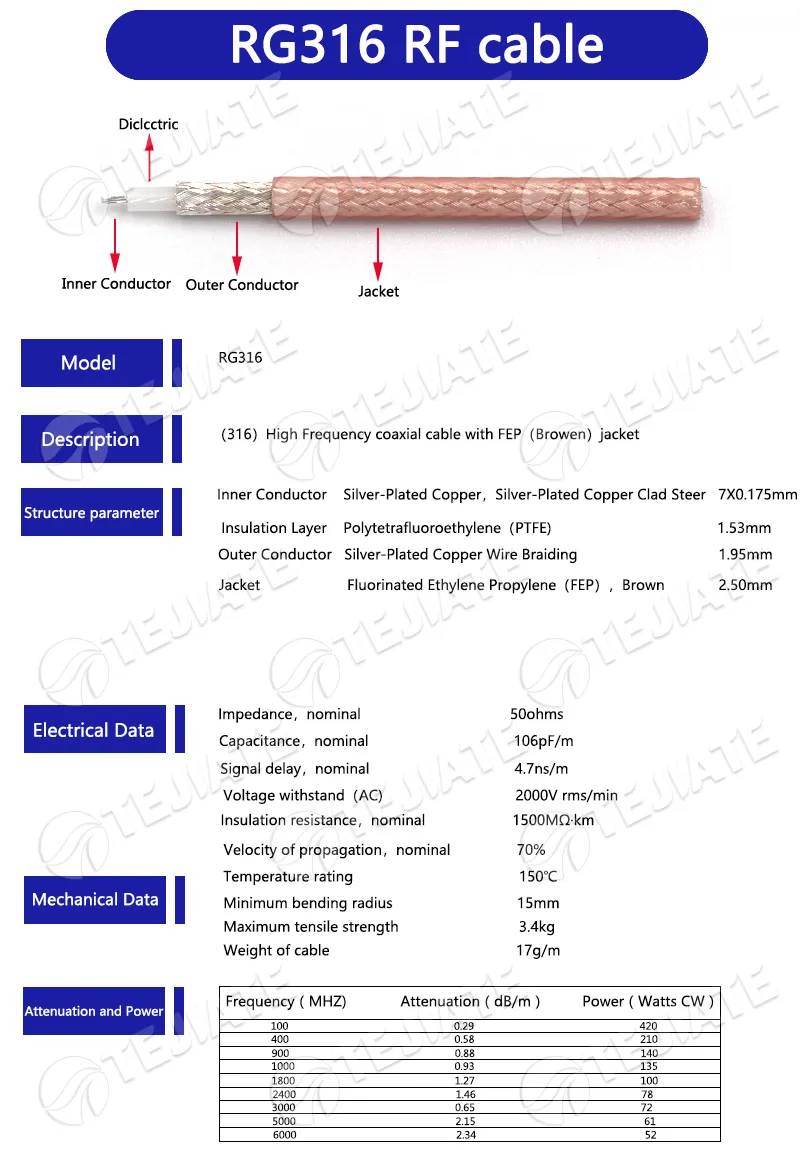

RG316/RG316D for short jumpers; check 10×OD minimum bend near boots

Provides a detailed cutaway view and tabulated specifications for the RG316 cable, including its inner conductor, dielectric, shielding, jacket materials, impedance, capacitance, attenuation values at various frequencies, power handling, mechanical data like bend radius, and temperature rating.

Inside most enclosures, RG316 and RG316D strike the best balance. They hold their shape well enough to avoid unexpected drift but still snake through tight harnesses. The practical rule many field engineers use—regardless of the connector vendor—is to keep bends near the feedthrough above roughly ten times the cable diameter. That’s not a hard failure threshold; it’s about maintaining stable return loss.

Boots and dust caps add thickness around the connector body, so the bend radius calculation should include them. A jumper that bends cleanly without boots may become marginal once the boot is installed. In RF cabinets where space is tight, this tiny detail affects repeatability far more than most spec sheets suggest.

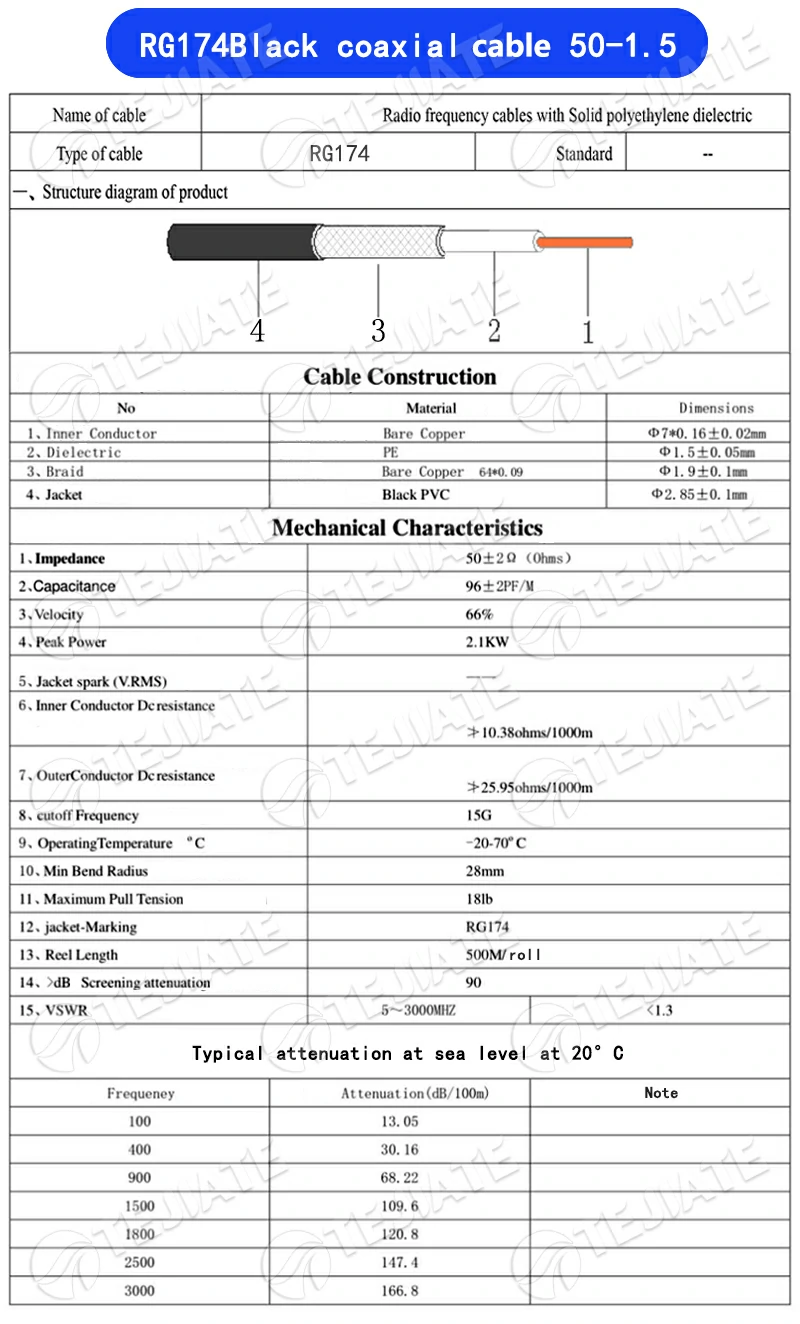

Compare with RG174 when flexibility vs loss is the constraint

This image is a technical illustration or cross-section photograph that breaks down the components of RG174 coaxial cable, the "workhorse of consumer Wi-Fi setups" as described. It visually details the layers listed in the spec table: 1) The central Bare Copper Conductor (7 strands of 0.16mm). 2) The white PE (Polyethylene) Insulation layer. 3) The Bare Copper Braid shield. 4) The outer Black PVC Jacket. This helps users understand the materials and construction that define the cable's flexibility, electrical properties (50 Ω impedance, ~0.82 dB/m loss at 2.4 GHz), and its limitations (higher loss at 5 GHz).

There are cases where RG174 outperforms RG316—not electrically, but mechanically. If a cabinet requires extreme routing flexibility or repeated motion (for example, a hinged plate or a service panel that swings open several times a day), RG174’s softer jacket can reduce mechanical fatigue.

The trade-off is straightforward:

- RG316 to lower loss, better high-frequency behavior, stiffer

- RG174 to higher loss, lower power, but far more flexible

Choosing the better one depends on what the feedthrough “sees” over its lifetime. A slightly higher-loss cable is usually acceptable if it prevents a chronic bend that slowly degrades an otherwise stable chain.

What recent RF news should influence enclosure routing choices?

Most enclosure routing discussions focus on mechanics—where the cables go, how sharp the bends are, and how many interfaces you can tolerate. But RF standards shift quickly, and those shifts tighten budgets in ways that directly influence feedthrough placement.

Three developments—3GPP Release-19, FCC Authorised Frequency Coordination for 6 GHz, and IEEE’s 2024 Wi-Fi timing updates—are already pushing engineers to reduce unnecessary interfaces, shorten jumpers, and refine grounding paths around the panel.

3GPP Release-19 freeze timeline to tighter RF budgets for field gear

With 3GPP Release-19 approaching its freeze milestone, more designs are leaving less room for sloppy feedthrough routing. As mid-band and unlicensed-band integration grows, insertion-loss budgets shrink. That’s why even a simple SMA-to-SMA adapter—often added as a shortcut—gets questioned during system reviews.

If your enclosure currently uses a long internal sma extension cable, or if the design relies on multiple adapters to fix direction issues, the Release-19 transition is a good moment to simplify. Fewer interfaces, shorter pigtails, and cleaner grounding reduce the risk of cumulative loss blowing up your margin later.

FCC 6 GHz AFC approvals boost rooftop/AP deployments to more sealed feedthroughs needed

Standard-power Wi-Fi in the 6 GHz band is finally expanding under the FCC’s Automated Frequency Coordination framework. With more rooftop and pole-mounted access points expected over the next few years, installers will rely more heavily on sealed sma feedthrough hardware to avoid moisture creeping toward the radio.

Cabinets on rooftops flex, heat-cycle, and accumulate dust. A connector that works indoors doesn’t automatically survive outdoors. This shift toward high-power APs makes IP67 sealing and correct stack-up more important than ever.

IEEE 802.11-2024 improves Fine Timing Measurement to cleaner 50-Ω chains matter

The updated IEEE 802.11-2024 spec brings improvements in Fine Timing Measurement across wide channels, especially around 320 MHz bandwidths. Precise time-of-flight calculations don’t tolerate sloppy return-loss behavior. As a result, enclosure routing that once “barely passed” will start showing measurement jitter if the cable path flexes too much.

In practice, this pushes engineers to minimize interface count and keep the jumper stable—exactly the scenario where choosing a right-angle or straight feedthrough correctly makes a measurable difference.

How do you order the exact SKU with zero back-and-forth?

Ordering an sma feedthrough should not require ten emails and a PDF exchange. Yet it often does, because engineers forget to specify orientation, thread length, or panel thickness. Procurement teams experience this constantly: a part matches electrically but fails mechanically because someone assumed the panel was “around 2 mm.”

A clean handoff comes from writing the order the same way you’d brief a technician. The mechanical constraints, sealing needs, and jumper geometry all belong in the same message. When done right, both sides avoid re-spins, and the part arrives exactly as expected.

Specify: SMA gender (M/F), orientation, straight/RA, panel range, O-ring, color, jumper length

A complete order usually includes:

- SMA gender on inside and outside

- Straight or right-angle body

- Panel thickness range (don’t forget coating)

- Thread length requirement

- O-ring needed or not

- Preferred color or plating (nickel, gold, black-oxide mechanical)

- Internal jumper length, especially for RG316 cable assemblies

This is where a single natural internal link helps: TEJTE’s panel-mount SMA pages provide examples of common thickness ranges and washer stacks without overwhelming the reader, so linking to their SMA bulkhead mounting logic serves as a quick reference rather than a promotion.

Include docs: RoHS/REACH, torque note, serialization

Finally, attach supporting documents:

- RoHS and REACH requirements

- torque recommendations

- serialization or lot-tracking needs

Many engineering teams also include a brief torque note to avoid overtightening during installation. It’s a small detail, but it prevents cracked dielectric, loose seals, or deformation of thin-wall panels.

SMA Feedthrough Stack-Up & IP Check

Selecting an SMA feedthrough for a panel isn’t just a mechanical choice—it’s a small engineering calculation. The goal is predictable engagement, predictable O-ring compression, and predictable RF behavior. Many field reliability issues trace back to small stack-up mistakes, so a simple check helps avoid surprises.

Below is a practical, engineer-friendly “fit check” table. It reflects what technicians actually verify when installing sma bulkhead cable assemblies inside sealed cabinets using RG316 or RG174 jumpers.

SMA Feedthrough Stack-Up & IP Fit Table

| Parameter | What You Enter | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Panel thickness (mm) | Actual measured thickness, including coating | Paint/anodizing often adds 0.1-0.2 mm; ignoring it shifts O-ring compression. |

| Thread length (mm) | Usable threaded portion on the feedthrough | Determines how much engagement remains after the panel + washers. |

| Washer height (mm) | Total height of flat/star washers | Affects mechanical bite and EMI bonding. |

| O-ring cross-section (mm) | Physical O-ring diameter | Used to estimate compression %. |

| Desired compression (%) | Usually 15-25% | Keeps the IP rating consistent without over-crushing the seal. |

| Clearance inside/outside (mm) | Real space available for boots or RA plugs | Prevents cable over-bending especially for RG316 cable assemblies. |

| Cable OD (mm) | Outer diameter of RG316, RG174, or selected cable | Helps determine the minimum bend radius. |

| Min bend rule (×OD) | Typically 10× cable OD | Maintains predictable return loss. |

| Interfaces count | Total connectors in the chain | Each interface adds small insertion loss; stacked losses degrade high-frequency margin. |

| Loss budget (dB) | Allowed total system insertion loss | Ensures the feedthrough + jumper stay within RF spec. |

How the evaluation works

- Engagement check:

Subtract the panel thickness and washer height from the feedthrough’s thread length.

If the remaining thread depth is at least about 80% of the nut height, the mount is typically secure.

- O-ring compression check:

Compare the expected squeeze against the O-ring’s cross-section.

A range of about 15–25% is where most seals perform well long-term.

- Bend-radius check:

Multiply the cable OD by the minimum bend factor (commonly ten).

If your available space is smaller than that radius, the jumper becomes a long-term failure point.

- Insertion-loss check:

Multiply the number of interfaces by the typical per-interface loss.

Add that to the jumper’s own loss.

If the total exceeds your budget, you’ll need fewer adapters or a shorter sma extension cable chain.

This simple reasoning process helps catch 90% of installation problems before the panel is drilled.

FAQs

Q1. How far can I extend an SMA cable before the link starts to fall apart?

Q2. What’s the cleanest method to bring an SMA connection out of a sealed enclosure?

Q3. I need to attach an SMA or RP-SMA connector onto coax—any red flags?

Q4. Which cable families normally pair well with SMA feedthroughs?

Q5. Does using a right-angle SMA plug hurt RF performance?

Q6. With more 6 GHz Wi-Fi deployments coming, should I rethink my feedthrough design?

Q7. Is IP67 enough for long-term outdoor work?

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.