RG316 Coax Guide: Specs, Loss, Bend Rules & Lab Use

Nov 20,2025

Preface

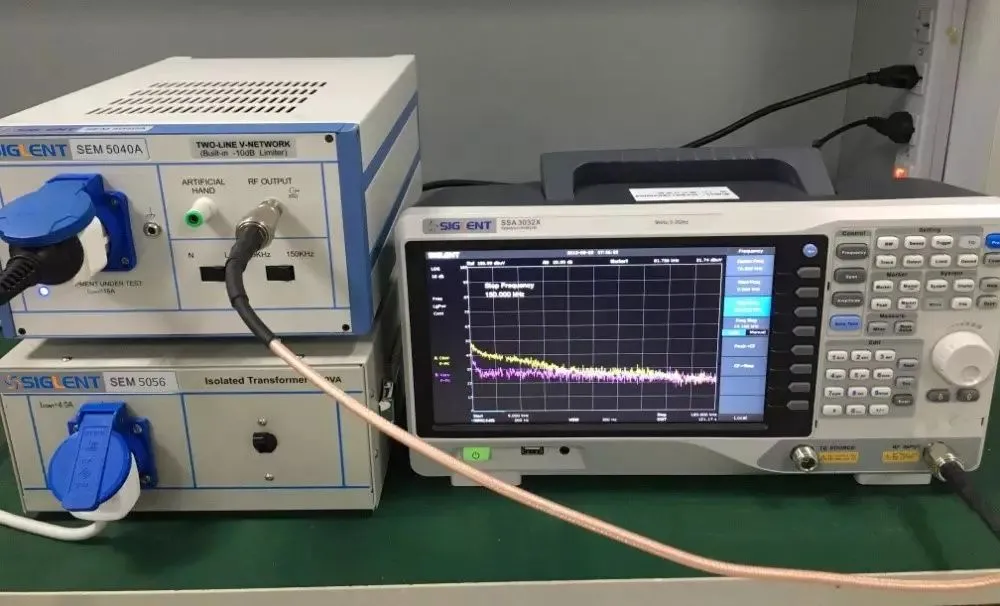

This image illustrates the physical characteristics of RG316 cable, emphasizing its slim profile, flexibility, and brown FEP jacket. It highlights how the cable maintains predictable performance even under stress, such as when squeezed or bent in crowded bench setups.

The diagram provides a cross-sectional view of RG316 cable, listing materials such as silver-plated copper conductor, PTFE dielectric, and FEP jacket with exact diameters. It also displays common connector types (e.g., BNC Male, SMA Male) used in RF applications for reliable interfacing.

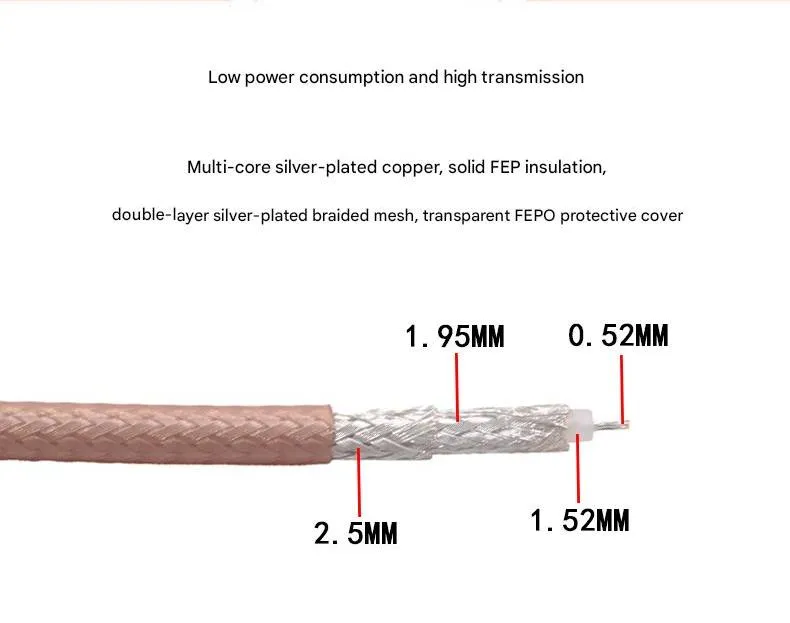

This image showcases RG316D cable's advanced construction, including multi-core silver-plated copper, solid FEP insulation, and a double-layer silver-plated braided mesh for improved shielding. The transparent FEPO protective cover allows visual inspection, making it ideal for high-frequency applications.

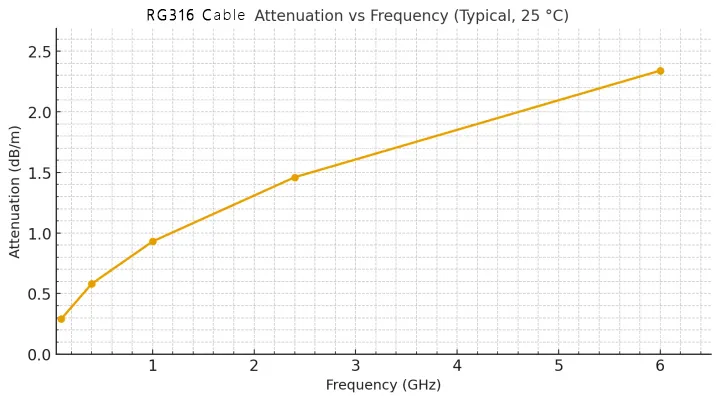

Your dataset reinforces this point with real figures instead of vague claims. The cable’s attenuation curve—0.29 dB/m at 100 MHz, 0.93 dB/m at 1 GHz, 1.46 dB/m at 2.4 GHz, and 2.34 dB/m at 6 GHz—lines up with what engineers see on analyzers every day. The mechanical numbers are just as important: 15 mm minimum bend radius for RG316, 13 mm for RG316D, tensile strength around 3.4 kg, and jacket temperatures ranging from 150 °C to 255 °C depending on construction. These constraints shape how long a jumper should be, how tight its routing can get, and how many cycles it truly survives.

With those real parameters as the baseline, the next few sections walk through the practical decisions engineers make when sizing, bending, and loss-budgeting rg316 coax—decisions that research papers rarely capture but every lab technician knows well.

How do you size an RG316 coax run for your bench?

Choosing the right jumper length is less about a formula and more about avoiding the two failure modes engineers see most often: unnecessary attenuation and connector strain. The electrical argument is simple—shorter cables reduce loss. But go too short and the cable tugs at SMA ports, twists during torqueing, or wedges between equipment panels. Most labs eventually learn that the “perfect” length is the shortest one that doesn’t feel tight.

For DUT fixtures, canned RF modules, or shield boxes, 0.1–0.2 m RG316 is typical. The loss is barely noticeable: 0.15 m at 2.4 GHz only adds ~0.22 dB, and the reduced loop area helps when routing near noisy DC-DC converters.

On general-purpose benches, 0.3–0.6 m tends to be the sweet spot. It lets you reach comfortably between analyzers, generators, and DUTs without piling up loops. Many teams standardize around 30 cm and 50 cm lengths because these sizes keep setups predictable. The approach mirrors the conventions seen in SMA male-to-female routing—if the cable geometry is consistent, you avoid half of the mechanical surprises before they happen.

Inside racks or sliding-tray systems, 1–2 m cables often work better than shorter ones. Yes, attenuation increases—1.5 m at 2.4 GHz adds around 2.19 dB—but that trade-off is small compared with preventing sideways force on SMA jacks. When deciding between “slightly too long” or “slightly too short,” the longer option almost always wins in mechanical reliability.

Pick practical presets (0.1–0.6 m; 1–2 m) without over-looping

The image demonstrates how RG316 jumpers are deployed in various lab scenarios, such as 0.1-0.2m for tight fixtures, 0.3-0.6m for bench routing, and 1-2m for racks. It emphasizes avoiding over-looping to prevent damage and maintain impedance stability over time.

Most teams end up relying on preset lengths simply because it reduces cognitive load:

- 0.1–0.2 m: tight fixtures, card-edge SMA, compact DUTs

- 0.3–0.6 m: instrument to DUT bench routing

- 1–2 m: racks, chamber feedthroughs, movable carts

The real issue isn’t the length—it’s the slack. Over-looped RG316 rubs against sharp chassis edges, picks up heat from nearby equipment, or accumulates twist stress. PTFE doesn’t complain immediately, but repeated tight looping eventually reshapes the dielectric and harms impedance stability.

Balance strain vs loss in tight racks

In racks, mechanical behavior matters more than electrical loss. SMA connectors may be rated for ≥500 cycles, VSWR below 1.10–1.20, and insertion loss around ≤0.15 dB @ 6 GHz, but these ratings assume axial stress. Few SMA ports survive long when the cable is angled downward or sideways under tension.

A jumper that’s 10–15 cm too short quietly transfers torque into the port every time the rack vibrates, a drawer slides, or a tech bumps the cable. Many RMA cases trace back to this exact scenario. A slightly longer rg316 cable eliminates that side-loading without meaningfully affecting loss. These subtle mechanical considerations are often more important than the raw attenuation values.

How much insertion loss should you expect at your frequency?

This chart plots attenuation (dB/m) against frequency (GHz) for RG316 cable, with values like 0.29 dB/m at 100 MHz and 2.34 dB/m at 6 GHz. It helps engineers quickly estimate loss for specific lengths and frequencies, supporting practical decision-making in lab setups.

Planning insertion loss becomes far less mysterious once you rely on real attenuation numbers. Your RG316 curve—0.29 dB/m @ 100 MHz, 0.58 dB/m @ 400 MHz, 0.93 dB/m @ 1 GHz, 1.46 dB/m @ 2.4 GHz, and 2.34 dB/m @ 6 GHz—makes it possible to approximate loss on the fly.

Take a standard 0.3 m jumper at 2.4 GHz:

Cable loss ≈ 0.44 dB

Add SMA interfaces—roughly 0.05–0.15 dB each—and the total often ends up around 0.55–0.75 dB for most clean two-connector chains.

Connector geometry subtly affects this. Straight SMA connectors typically maintain tighter field symmetry and slightly lower loss. Right-angle SMA, although convenient in tight builds, usually raises VSWR by a small margin. When mixed-interface chains include SMA to BNC transitions, engineers sometimes minimize IL by using a single short jumper rather than a stack of adapters, as reflected in short RG316 jumper practices.

Mismatch also contributes. Even a modest VSWR increase changes reflection coefficient ρ and adds a fraction of a decibel to the total IL. While PTFE remains stable across −55 °C to +150 °C, connectors can shift slightly under thermal cycling, which indirectly influences mismatch rather than core cable loss.

Inputs & formulas for quick budgeting

Your calculator uses real-world engineering relationships:

- Cable loss = α × length

- Interface loss = N × IL per connector

- Mismatch loss = −10·log₁₀(1 − ρ²)

- Total IL = cable + interfaces + mismatch

These numbers help engineers decide whether a path needs a shorter jumper, fewer transitions, or improved VSWR at a specific band.

When a shorter jumper beats adding another adapter

What bend radius and jacket choices protect durability?

RG316’s reputation for durability comes from respecting a few mechanical boundaries. PTFE is wonderful electrically but doesn’t like being creased. Your RG316’s 15 mm minimum bend radius (or 13 mm for RG316D) sets a clear limit. Once you go sharper, the dielectric stores the deformation and slightly disturbs impedance—a bump that often appears as ripple or small VSWR spikes.

The FEP jacket tolerates heat, abrasion, and solvents better than PVC or PE, but even FEP wears when dragged across textured aluminum. If the jacket thins enough to expose the braid, moisture and mechanical fatigue accelerate rapidly. High-reliability racks avoid this by routing cables through smooth grommets or nylon clamps rather than bare panel edges.

Thermal behavior also matters. RG316 is comfortable up to 150 °C, and RG316D stretches into the 255 °C range thanks to its dual silver-plated braid and heavier jacket. Although you rarely operate that high, this margin protects the cable inside sealed enclosures or near warm RF stages. Practically, the thermal headroom prevents long-term property drift.

PTFE dielectric, FEP jacket; single vs double shield (RG316D)

Minimum bend ≈ 10×OD near boots; avoid repeated sharp bends

A rule engineers swear by:

If the cable holds its shape after bending, the bend was too sharp.

Avoid bending near the SMA boot—the transition between the rigid connector and flexible jacket sees the most stress. Keeping bends at least 10× the outer diameter from that joint extends cable life and reduces the chance of impedance discontinuities. Repeated bending in the same spot, especially where the cable exits a connector, slowly work-hardens the braid and fatigues the dielectric. Light support—plastic clamps, soft guides, or thoughtful routing—goes a long way toward keeping a jumper stable over thousands of hours.

Can RG316 vs RG174 be swapped without breaking the spec?

This close-up image showcases TEJTE's RG316 high-frequency coaxial cable. Its key features include an extremely slim outer diameter (~2.5mm) and high flexibility (minimum bend radius of only 15mm), making it ideal for high-density wiring, test bench jumpers, and internal connections in IoT modules. The cable uses PTFE insulation and a silver-plated copper braid, ensuring stable performance at temperatures up to 150°C and maintaining good signal integrity at frequencies up to 6 GHz. The brown FEP jacket provides additional heat resistance and durability.

The image positions RG174 for short in-box extensions—very flexible, but loss rises quickly at higher GHz and longer runs.

RG316 and RG174 may look similar at a distance—they’re both thin, flexible, and common in small RF harnesses—but substituting one for the other isn’t always safe. Their electrical and mechanical behaviors diverge in ways that matter once frequency climbs above the low-MHz range. RG316 relies on a silver-plated copper conductor, PTFE dielectric, and an FEP jacket. RG174 typically uses a tinned-copper conductor with a polyethylene dielectric, giving it a noticeably lower temperature rating and less stable impedance.

Your attenuation data makes the difference easy to quantify. While RG316 measures 0.93 dB/m at 1 GHz and 1.46 dB/m at 2.4 GHz, RG174 commonly runs 1.5× or more above those values. That’s why RF benches handling Wi-Fi, GNSS, LTE, or ISM-band measurements usually depend on RG316 or RG316D. Low-loss performance is part of the story, but temperature drift and dielectric stability matter just as much.

Shielding also separates the two. RG316D adds a second silver-plated braid, creating tighter shielding effectiveness and better immunity to coupling from switching regulators or digital buses. RG174’s single braid is perfectly adequate in low-frequency or noncritical applications, but it’s more vulnerable to noise pickup in dense electronics.

There are still cases where RG174 is appropriate—long, low-frequency harnesses, ultra-flexible routing, or battery-powered IoT devices. But substituting RG174 into a 2–6 GHz test chain built around rg316 coax typically raises insertion loss, increases mismatch, and undermines repeatability. Mixed-connector environments, especially those involving SMA to BNC transitions, reinforce this point; many engineers maintain signal integrity by following practices outlined in short RG316 jumper vs adapter chains rather than switching cable families.

Shielding, attenuation, flexibility: when to step up cable class

You step up to RG316 or RG316D when:

- The cable passes near switching power stages or fast digital clocks

- Sensitivity is high (GNSS, SDR front ends, low-power receivers)

- Test signals extend into multi-GHz bands

- You require temperature stability across wide cycles

- Shielding margin matters more than ultra-soft flexibility

RG174 still works when the priority is extreme flexibility, weight savings, or modest bandwidth. But for most commercial RF benches, RG316’s construction simply delivers more predictable results.

Keep 50-Ω end-to-end; use pads only when mixing systems

Another issue with swapping cable families is impedance discipline. Even if RG316 and RG174 both nominally specify 50 Ω, connector tolerances and dielectric properties differ. A chain that was originally designed around RG316 may drift toward mismatch when RG174 is inserted, especially at higher frequencies.

If you must connect a 75-Ω device—video gear, CATV tuners, or certain SDR modules—it’s better to use a resistive pad or impedance-matching adapter than to rely on cable substitution. Maintaining an honest 50-Ω path reduces VSWR, lowers mismatch loss, and keeps phase behavior predictable.

How do you map SMA male to SMA female correctly on assemblies?

The image provides a clear reference for SMA connector mapping, showing types like SMA-J (female) and SMA-K (male), including reverse polarity (RP-SMA) options. It explains how straight connectors maintain lower VSWR, while right-angle types reduce mechanical strain in tight spaces.

SMA gender mapping is one of those deceptively simple tasks that causes a surprising number of test failures. SMA male carries the inner pin, while the SMA female carries the inner socket—yet variations like extended-thread bulkheads, right-angle connectors, panel-mount types, and PCB-edge jacks complicate the picture.

Most instruments—spectrum analyzers, signal generators, VNAs—use SMA female ports. That means your coax assembly must present an SMA male at the instrument side. On DUTs, the connector may be an edge-mount female or a panel bulkhead, so again the jumper usually ends in an SMA male. The simplest mistake is ordering a female-to-female cable when both devices expect a male.

Right-angle SMA connectors add another layer of nuance. Their geometry slightly disturbs the internal field, leading to marginally higher VSWR compared with straight types. Your component data reflects this: straight SMA variants often stay under 1.10, while right-angle types hover just under 1.20. For precision paths—calibration lines, phase-critical links—straight connectors are typically the safer choice.

Labeling practices help. Engineers often mark heat-shrink near the boot with gender labels, length codes, or routing arrows. Keeping a standard set of jumper templates—150 mm, 300 mm, 600 mm with predictable SMA mapping—also prevents mix-ups. These habits align with the routing discipline captured in SMA male-to-female mapping guides, especially in environments with repeated reconfiguration.

Straight vs right-angle ends and where each makes sense

Straight SMA connectors excel when:

- Loss and VSWR must stay ultra-low

- The chain includes calibration standards

- High-frequency work extends toward 6 GHz

- Mating cycles are frequent

Right-angle SMA connectors make sense when:

- Space is tight and clearance is limited

- Cables must turn immediately after the port

- Instrument ports risk mechanical strain without relief

Loss differences are small, but mechanical benefits often justify RA ends in constrained builds.

Labeling habits that prevent field swaps and RMAs

Small habits prevent large RMAs:

- Heat-shrink labels on each end

- Color coding straight vs right-angle assemblies

- Fixed cable geometries for common setups

- Torque notes in build documents

- Avoiding cables whose ends “look the same from a distance”

Many labs store their RG316 jumpers in trays sorted by connector geometry to reduce mis-mating.

Will power handling or VSWR limit your application?

Engineers often assume that because RG316 is thin, it must have a very low power ceiling. In reality, your RG316’s power ratings—420 W CW at 100 MHz, 135 W at 1 GHz, 78 W at 2.4 GHz, and 52 W at 6 GHz—are surprisingly strong for its size. The limiting factors aren’t always the conductor or dielectric; they’re usually VSWR, temperature, and connector transitions.

VSWR directly affects peak voltage inside the cable. A mismatch increases the reflection coefficient ρ and raises the stress on the PTFE dielectric. Your calculator’s derating approximation,

PowerDerate ≈ (1 − (T − 25)/ΔTmax) / VSWR,

captures the relationship between temperature rise and mismatch reasonably well. Even a modest VSWR like 2:1 can cut safe power margins in half.

Temperature and airflow matter too. RG316 is rated to 150 °C, while RG316D’s construction stretches the upper limit to 255 °C. Though these limits are high, enclosed racks and PA modules can create localized heating that pushes cables much closer to long-term drift thresholds. Heat accelerates jacket wear and can expand mechanical tolerances near SMA boots, subtly increasing mismatch.

Finally, interface count plays a big role. Each extra SMA or BNC adapter contributes 0.05–0.20 dB of IL and adds its own mismatch. This is why many engineers prefer a single clean sma extension cable over a chain of separate adapters. In mixed-connector benches, this approach almost always results in more stable power behavior and more predictable insertion loss.

Where does RG316 fit in recent RF lab updates?

As RF labs evolve to support wider channels and higher carrier frequencies, the role of RG316 hasn’t disappeared—it has simply shifted. Modern Wi-Fi 6/6E access points, small-cell 5G radios, and multi-band IoT modules all push benches to operate higher in frequency with denser instrumentation than before. In those environments, short rg316 coax assemblies still fill an essential niche: low-loss enough for instrument jumpers, flexible enough for tight fixture routing, and mechanically stable across long validation cycles.

You can see this trend clearly in practical deployments. In OTA chambers, for instance, antennas swing or rotate while DUT mounts slide in and out of position. A stiff cable would fight that motion; RG316’s PTFE-FEP construction tolerates the repeated micro-bends surprisingly well. Engineers working with Wi-Fi APs in thermal chambers often choose RG316 or RG316D for exactly that reason—it behaves the same after the fiftieth movement as it did on the first.

The same logic shows up in less exotic places too. Field technicians use RG316 jumpers inside hotel or stadium AP enclosures where space is tight and temperatures vary. Hardware teams debugging GNSS modules on embedded boards often rely on 15–20 cm RG316 pigtails because the cable can squeeze between shields without detuning the RF path. Even home lab setups—NAS servers with external SMA antennas, SDR receivers, or streaming rigs—quietly benefit from RG316’s predictable loss and bend behavior.

Lab modernization also favors predictable jumper geometries. Many teams have standardized around 150 mm, 300 mm, and 600 mm assemblies with consistent SMA male/female mappings. Keeping paths consistent prevents tiny impedance discontinuities from creeping in when setups are rebuilt, and it cuts down on the “why is the sweep different today?” moments. Similar routing discipline appears across TEJTE’s broader RF connector families, such as the practices captured in instrument-grade SMA chain design.

Another trend is the rise of hybrid benches combining SMA, N-type, and BNC ports. Even as newer test sets introduce wider instantaneous bandwidth, RG316 jumpers continue to serve as the “glue” linking legacy modules with modern instruments—especially in racks where space is limited and motion is unavoidable.

Wider channels & higher bands push for shorter, cleaner paths(Wi-Fi/5G labs)

As channel widths expand—40 MHz, 80 MHz, 160 MHz—and carrier frequencies rise, small discontinuities matter more. RG316’s attenuation at 2.4–6 GHz is modest for short lengths, but long, loosely managed jumpers introduce phase ripple and small mismatch artifacts that become visible in OFDM-based measurements.

Keeping paths short reduces these effects. Straight SMA connectors also help maintain phase stability when capturing S-parameters or performing sensitivity tests at the upper end of a DUT’s operating band.

Standardize lengths and RA options to reduce strain on instrument ports

Repeated repositioning of DUTs, test heads, and antennas takes a toll on SMA ports. Fixed-length RG316 assemblies with consistent straight/RA mappings prevent sideways force on instrument front ends and avoid the slow drift in VSWR that appears once ports loosen internally.

Standardization also makes troubleshooting easier—engineers know exactly how long each path is, how it should be routed, and what insertion loss to expect at common bands like 900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, and 5.8 GHz.

Order exactly what you need, step by step

Ordering an rg316 cable assembly is easier when you break the selection into deliberate steps rather than picking length and connector type on instinct. Start with the electrical constraints: length, frequency, allowable loss, and the number of interfaces. Using your attenuation data, the difference between a 0.3 m and 0.5 m jumper at 2.4 GHz is only ~0.29 dB—a figure small enough that mechanical routing often dominates the decision.

Next, choose connector geometry. Straight SMA connectors minimize mismatch and maintain predictable VSWR. Right-angle versions help relieve strain where space is tight or the cable must turn immediately after the port. Bulkhead and feedthrough styles come into play when panels or enclosures are involved.

Color-coded jackets or labels simplify future maintenance, especially in dense test racks. Documentation is also worth including—many labs attach torque notes, serialization, or compliance information (RoHS/REACH) directly to the assembly order. This approach mirrors the practices common in TEJTE’s own RF accessory ecosystem, where repeatability matters more than one-off customization.

Finally, avoid chaining adapters unless absolutely necessary. A single clean sma extension cable almost always outperforms a chain of mixed SMA/BNC/N-type adapters in both IL and long-term mechanical reliability.

Choose length, straight/RA, bulkhead/feedthrough, jacket color

A practical ordering list might look like:

- Length: 0.15 m, 0.3 m, 0.5 m, 1 m

- Connector A: SMA male (straight or RA)

- Connector B: SMA male/female depending on DUT

- Optional: bulkhead, extended nut, or feedthrough

- Jacket: standard FEP or color-coded variants

- Labeling: heat-shrink identification at both ends

Consistency simplifies calibration and long-term maintenance.

Add documents: RoHS/REACH, serialization, torque note

Many engineering teams attach manufacturing details to the order:

- Compliance documents for audits

- Serialization or QR codes for traceability

- Recommended torque values (e.g., 8 in-lb for SMA)

- Optional IL measurements at a defined frequency

Well-documented assemblies make troubleshooting easier months or years after deployment.

FAQs

1. How much power can RG58 vs RG316 actually handle?

2. How do I connect an RG316 cable to a FrSky RX cleanly?

3. How should I use RG316 for an RX antenna lead?

4. Is there a better low-loss alternative to RG316 for longer runs?

5. What does “low-loss RG316” really mean?

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.