SMA Crimp Connector: Complete Guide to Strip, Crimp & Inspect

Oct 7,2025

Introduction

This figure appears at the beginning of the document to set the context, emphasizing how a poorly executed crimp can compromise an entire RF system's reliability. It introduces the detailed guide on correctly selecting, crimping, and inspecting connectors that follows.

In RF and high-frequency engineering, a poorly executed crimp can ruin an otherwise flawless design. The SMA crimp connector has become a staple in network communications, test equipment, and even aerospace hardware because it balances compact size with a reliable 50-ohm interface. Yet anyone who has wrestled with intermittent links knows the reality: the small details — strip length, crimp height, and pull strength — determine whether a connection stays rock-solid or fails at the worst moment.

This guide is built to help you avoid those headaches. We’ll walk through the process step by step, from selecting the right coaxial cable to confirming that the ferrule compresses exactly within tolerance. Along the way, we’ll compare SMA male connectors with SMA female connectors, point out when an RP-SMA variant is the correct choice, and explain how popular cables such as RG316, RG174, and LMR200 behave in real deployments.

One note from experience: don’t underestimate the role of materials. Many TEJTE SMA connectors use PTFE insulation and corrosion-resistant gold-plated brass, so they can survive harsh environments, from humid outdoor towers to lab benches running hot at 150 °C. That resilience explains why crimped SMA assemblies appear everywhere — from 5G base stations and Wi-Fi gear to avionics and automated factory systems.

Whenever deeper specs or application examples are needed, you’ll find links to related resources on TEJTE’s blog and product categories. They’re useful checkpoints if you want to cross-verify data, explore ordering options, or simply see how others are solving similar design challenges.

How do I pick a 50-ohm cable and matching crimp set?

Cable–terminal compatibility (RG316, etc.)

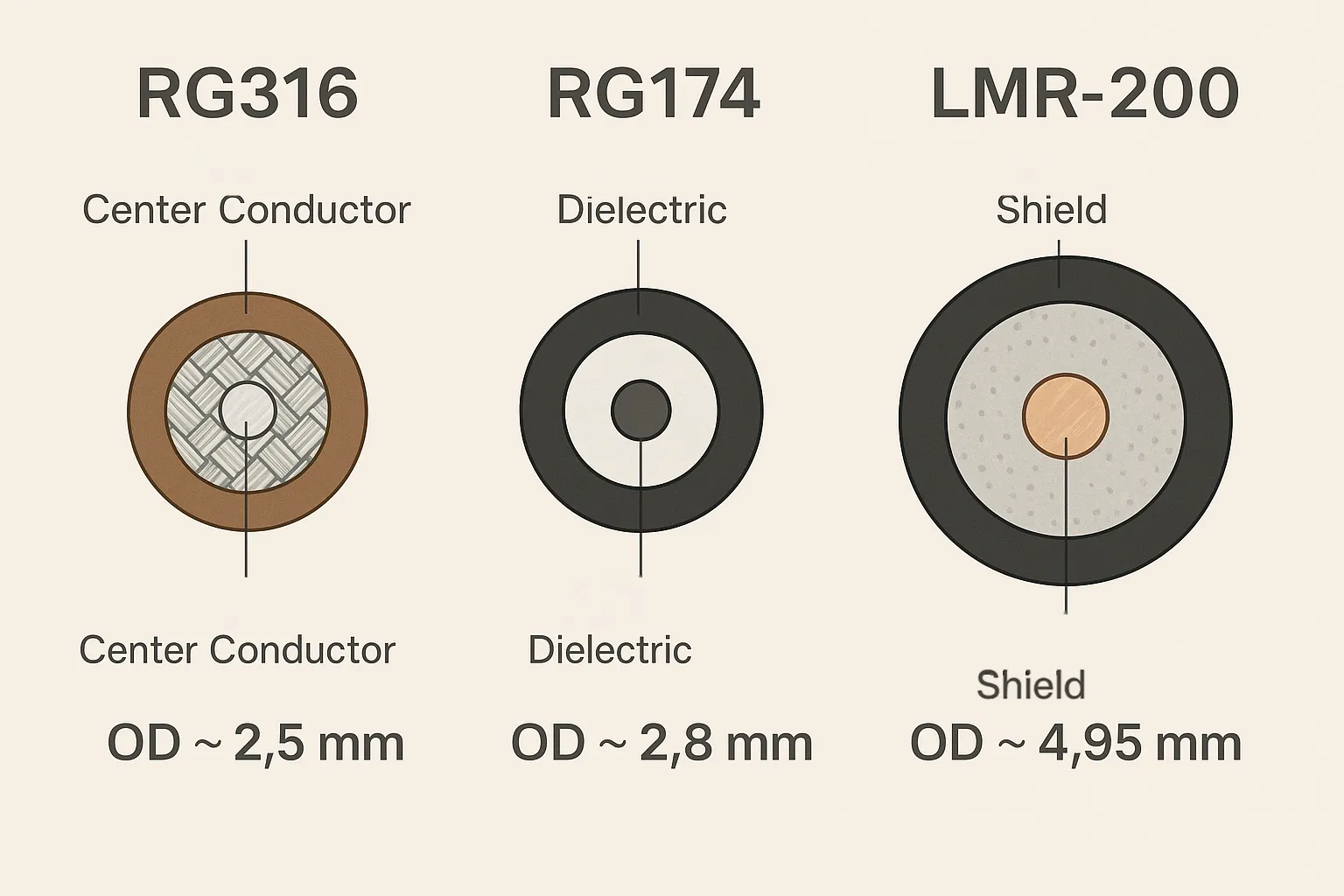

This figure provides a visual comparison of the physical structures of different coaxial cables, including the center conductor, dielectric, shield, and outer diameter. The document uses this to illustrate how different cable types require specific strip lengths and ferrule sizes, forming the basis for understanding cable-connector compatibility.

- Different coax types require specific strip lengths and ferrule sizes. Here’s how some of the most common 50-ohm cables line up:

| Cable Type | Inner Conductor | Dielectric Ø (mm) | Jacket Ø (mm) | Characteristic Impedance | Typical Connector Fit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG316 | 7×0.175 mm silver-plated copper | 1.53 | 2.50 | 50 Ω | SMA crimp (Hex 1.72-2.03 mm) | Flexible, wideband 0-6 GHz, loss ~0.93 dB/m @ 1 GHz |

| RG174 | 7×0.16 mm tinned copper | 1.50 | 2.85 | 50 Ω ±2 | SMA crimp (Hex 2.03 mm) | Higher attenuation, ≈68 dB/100 m @ 900 MHz |

| LMR-200 | Solid bare copper, 1.12 mm | 2.95 | 5.00 | 50 Ω | SMA/N-type crimp sets | Low-loss upgrade vs RG58, bend radius 25-50 mm |

Notice how subtle differences change the outcome. A RG174 jacket won’t fit snugly into a ferrule designed for RG316. If you force it, the braid density won’t compress evenly and return loss will spike. On the other hand, LMR200 offers far lower loss than RG58, but its larger diameter demands a bigger ferrule and careful handling during bends.

When in doubt, double-check datasheets or use resources such as the RF coaxial cable guide. It lays out impedance, attenuation, and construction differences in detail, making it easier to pick the right combination before you start crimping.

Gender/polarity ID: SMA vs RP-SMA

This figure is a key reference for identifying connector types. The document emphasizes that confusing SMA and RP-SMA is a common mistake leading to electrical incompatibility. By showing the center contact (pin or socket) and thread location, it helps users accurately distinguish between types to avoid procurement and assembly errors.

Misidentifying connector gender or polarity is one of the most common mistakes in RF builds. A SMA male connector carries a center pin, while the SMA female connector houses a socket. Straightforward enough — until you encounter RP-SMA (reverse polarity). In RP-SMA, the outer shell looks identical, but the pin and socket roles are swapped inside. To the untrained eye, they appear interchangeable, yet they will not mate correctly.

The cost of confusion can be more than a wasted part. An engineer who orders 200 wrong connectors for a Wi-Fi build may lose days waiting for replacements. A good rule of thumb is simple: don’t just check the threads, check the center contact. That single glance often saves a project from an unnecessary delay.

Take, for instance, TEJTE’s SMA-50KY. It uses a PTFE dielectric with copper contacts, operates from 0–6 GHz, and meets RoHS requirements. This is a standard SMA part. An RP-SMA version would look nearly identical, but its reversed pin orientation would make it electrically incompatible. It’s easy to see how such a subtle shift trips up purchasing teams.

If your project involves board launches, review the SMA connector on PCB layout guide before finalizing footprints. It covers polarity details, pad sizing, and via fencing that keep impedance stable once the connector is soldered or panel-mounted.

How do I “strip–crimp–inspect” in one pass?

Crimp Spec Card — strip lengths, hex size, crimp height, min pull, pass criteria

| Cable Type | Strip Lengths (mm) Jacket / Braid / Dielectric / Pin |

Hex Size (mm) | Crimp Height (mm) | Min Pull (N) | Pass Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG316 | 6.0 / 3.0 / 2.0 / 1.0 | 1.72 or 2.03 | 1.30 ± 0.05 | ≥ 34 N | No cracks, no braid intrusion, concentric pin |

| RG174 | 6.5 / 3.0 / 2.5 / 1.0 | 2.03 | 1.40 ± 0.05 | ≥ 18 N | Jacket not nicked, dielectric intact |

| LMR200 | 7.0 / 3.5 / 3.0 / 1.2 | 5.40 | 2.30 ± 0.10 | ≥ 60 N | Braid 360° coverage, no tilt |

Acceptance formula:

Pass = (All dimensions ∈ tolerance) ∧ (Crimp height within range) ∧ (Pull ≥ spec) ∧ (No cracks, off-center pins, or flared braid).

Here’s the reality check: crimp the ferrule just 0.1 mm too low on RG316, and you can lose up to 25% of pull strength. Once that happens, even a casual tug when routing cables inside a rack may cause the joint to fail. It’s one of those details that separates a “working” assembly from a robust one.

Tooling: strippers, hex dies, positioners, pull gauge

This figure shows the key tools essential for ensuring the crimping process meets specifications, such as strippers, hex crimp tools, positioner jigs, and a pull gauge. The document context stresses that using the right tools is as crucial as controlling strip length and crimp height for ensuring connector mechanical strength and electrical performance.

To stay within tolerance, the right tools matter as much as technique:

- Coax strippers with adjustable blades — set for ~2.5 mm jacket cut on RG316.

- Hex crimp tools with dies from 1.72–5.40 mm, covering thin RG174 up to thick LMR200.

- Positioner jigs that hold the pin concentric during soldering or crimping.

- Pull gauge (0–100 N) to confirm minimum pull strength after crimping.

Some technicians are tempted to skip the pull test, especially when production deadlines loom. Don’t. A connector may look flawless but still slip under stress. Think of the pull check as cheap insurance: twenty seconds with a gauge can prevent hours of rework and the embarrassment of a field failure.

For additional reference on strip and crimp practices, the complete SMA connector guide expands on torque and inspection methods.

What changes between male, female, and RP-SMA crimping?

Pin/socket nuances and common failure modes

- SMA male connector: The pin is easy to bend during insertion. If the conductor isn’t stripped cleanly, the PTFE dielectric can crack. A frequent mistake is letting solder wick into the pin barrel — this shifts the pin off-center and leads to return loss spikes.

- SMA female connector: The socket tolerates less axial misalignment. Uneven braid distribution before crimping can raise insertion force and distort the socket. Once damaged, it won’t reliably mate again.

- RP-SMA connectors: Common in Wi-Fi gear, they flip pin/socket roles. That means strip dimensions may look the same on paper, but the effective pin length is slightly different. If you don’t account for that, continuity tests may fail.

Common failure cases include:

- Over-crimp → ferrule pressed below spec, dielectric fractures, pull force drops fast.

- Under-crimp → braid not fully captured, creating intermittent ground contact.

- Braid intrusion → stray braid strands slipping into the pin zone, leading to shorts.

A practical tip: keep a small box of “failure samples.” Engineers often underestimate how much you can learn by handling a deformed pin or cracked dielectric. It’s a reminder of what not to repeat.

For more visual comparisons, the SMA male connector guide and the SMA female connector guide show torque practices and sealing methods that go hand-in-hand with crimping quality.

Straight vs right-angle tails: which survives stress better?

This figure appears in the context of discussing "loss caused by added adapters." It serves as a visual reminder that adding extra interfaces like adapters into an RF path introduces insertion loss and mismatch, emphasizing the principle of minimizing adapter cascades in test setups.

This figure is referenced when discussing "when to switch to a short extension cable." The document suggests that using a short SMA jumper is often smarter than forcing a right-angle connector when enclosure space demands a sharp bend, as the jumper absorbs flex stress in the cable rather than at the connector joint, improving reliability.

This figure is used for comparison with the right-angle connector. The document states that straight connectors direct load along the cable's axis, thus typically showing higher tensile strength and are preferred for handling pulls. They demonstrate more stable performance in tensile tests.

This figure shows the structure of a right-angle connector. The document explains that right-angle connectors transfer bending loads directly into the pin and dielectric (the weakest parts), making them generally less resistant to bend and pull fatigue compared to straight connectors. They are suitable for space-constrained applications where frequent bending is avoided.

When to switch to a short extension cable

Straight connectors almost always show higher tensile strength. For instance, a properly crimped RG316 SMA straight tail can withstand at least 34 N without deformation because the braid is compressed evenly around the dielectric. In contrast, a right-angle body tends to transfer bending loads into the pin and dielectric — the weakest parts of the assembly.

So what happens when enclosure space forces a sharp bend? In those cases, it’s smarter to use a short SMA extension cable instead of forcing the connector to carry the strain. A jumper built from RG316 or LMR200 takes up the flex stress in the cable, not the connector joint. In test racks where cables are plugged and unplugged daily, this small adjustment can prevent premature failures.

Practical note: if you see cracked jackets or intermittent signal drops near a right-angle tail, that’s usually a sign the connector has been over-stressed. Switching to a jumper early saves time later.

For mounting comparisons, see TEJTE’s SMA right-angle connector guide or browse SMA extension cable assemblies to find pre-made jumpers designed for tight spaces.

Straight pull vs angled stability

The trade-off is about space versus strength. In tensile tests, SMA straight crimps on RG174 maintained continuity after a 20 lb pull, while right-angle versions showed slight impedance drift. That doesn’t make right angles poor choices; it just means they require careful placement.

In compact wireless devices, a right-angle is often the only option to avoid mechanical interference with other components. The trick is understanding the stress path: if the cable will be bent repeatedly, reinforce it with heat-shrink tubing or, better yet, move the bend away by adding a short jumper. For stationary panel-mount cases where the connector won’t move, the SMA right angle connector is perfectly acceptable.

How do I mate a crimped tail to PCB/panels reliably?

Launch pads, via fences, torque & panel sealing

When coax transitions into a board, impedance control can’t stop at the connector’s ferrule. The SMA to PCB interface must be treated as part of the transmission line:

- Pad sizing and via fences: Match the launch pad diameter to the connector’s pin and surround it with ground vias (≤1 mm pitch) to contain fields.

- Keep-out zones: Provide clearance around the connector body. Without it, torque can crack solder mask or stress nearby traces.

- Torque range: For SMA panel nuts, tighten to 0.45 ± 0.05 N·m. Too little torque, and the nut will loosen over time; too much, and the PTFE dielectric may deform.

- Sealing: Use O-rings and anti-rotation washers in environments with vibration or moisture.

Take TEJTE’s SMA/MCX-KKY as an example. With a hex size of 8 mm, 1/4-36 UNS threads, and a PTFE dielectric, it stays aligned even under thermal cycling when installed with the supplied lock washer. For PCB design tips, the SMA connector PCB layout guide covers pad and via details that help maintain a 50-ohm launch.

Panel pass-through and anti-loosening

When crimped cables need to exit an enclosure, a feed-through adapter is often the safest bet. The SMA-KKY dual-female adapter (22.2 mm body, gold-plated brass, RoHS compliant) allows easy mating both inside and outside a chassis. Its serrated washer helps prevent rotation — a small detail that dramatically extends connector life in field equipment.

Even the best crimp can fail if the connector isn’t mechanically secured. That’s why TEJTE’s panel-mount SMA connectors ship with nuts, lock washers, and gaskets. These small accessories keep assemblies tight, which matters as much as the crimp itself.

How much loss do added adapters cause, and what to prefer?

Use minimal cascades; prefer short jumpers in labs

Imagine connecting SMA gear to BNC test equipment. You’ve got two choices:

- Use a single SMA to BNC adapter.

- Chain a short SMA jumper, then an adapter, then the BNC.

Option one is usually better because fewer transitions mean less loss. But in cramped racks or benches, geometry may force option two. In that case, the safest approach is to keep the jumper short and pick a low-loss cable like LMR200.

Here’s a comparison that engineers often use when planning setups:

| Setup | Frequency | Extra Loss (dB) | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single SMA-BNC adapter | 1 GHz | ≈ 0.15 | Minimal, fine for most testing |

| Two adapters in cascade | 1 GHz | ≈ 0.30–0.40 | Noticeable mismatch, not ideal for calibration work |

| Short 15 cm RG316 jumper | 1 GHz | ≈ 0.25 | Similar loss to cascaded adapters but gentler on connectors |

50-ohm chain management

Whichever option you choose, one rule never changes: maintain a 50-ohm chain. A 50 ohm SMA cable like RG316, RG174, or LMR200 has specific bend limits — 15 mm for RG316, 28 mm for RG174, 25–50 mm for LMR200. Exceeding those minimum bend radii can permanently distort impedance and raise loss.

At higher frequencies, these differences really matter. For example, RG316 attenuates about 1.46 dB/m at 2.4 GHz, while RG174 loses over 12 dB per 10 m at the same frequency. That’s the kind of margin that can flip a link from stable to unreliable.

When planning critical assemblies, cross-check attenuation charts in the RF coaxial cable guide. Knowing exactly how much margin you lose per meter helps avoid surprises once the system is deployed.

How do I complete incoming inspection in just 5 minutes?

IQC checklist — visual, dimensional, electrical, mechanical

| Category | Key Checks | Pass/Fail Threshold | Tools Needed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual | Plating uniform, PTFE dielectric intact, pins not bent | No visible cracks, scratches, or discoloration | Microscope / magnifier |

| Dimensional | Ferrule crimp height within spec (e.g., RG316: 1.30 ± 0.05 mm) | Within tolerance per spec | Vernier caliper / micrometer |

| Electrical | Continuity < 10 mΩ, insulation resistance > 500 MΩ | Meets or exceeds thresholds | DMM / megohmmeter |

| Mechanical | Pull ≥ spec (RG316 ≥ 34 N, RG174 ≥ 18 N, LMR200 ≥ 60 N) | No loosening or wobble after 10 flex cycles | Pull gauge |

Quick fault diagnosis

Not every site has a lab bench. When a failure shows up in the field, simple checks can still reveal the root cause:

- High contact resistance → Often from a bent pin or braid contamination inside the ferrule.

- Sudden return loss spike → Usually a cracked dielectric, especially in SMA female connectors where the socket wall is thinner.

- Connector heating → Too many cascaded adapters or poor braid continuity.

Field tip: if an assembly gets warm during continuous transmit, disconnect it immediately. Heat usually means mismatch or loss, and both shorten connector life.

For troubleshooting cases and prevention methods, you can also reference the SMA female connector guide, which highlights common socket issues under load.

What specs must I submit to suppliers to order once?

Spec packaging: gender, angle, cable type, plating, torque & QC

Here’s what should be in your RFQ:

- Interface: Specify SMA male connector, SMA female connector, or RP-SMA. Don’t assume the vendor can guess.

- Angle: Call out straight vs SMA right angle connector. Space constraints often dictate which works.

- Cable type & length: Be specific: RG316 (Ø 2.5 mm), RG174 (Ø 2.85 mm), or LMR200 (Ø 5.0 mm). Include length in centimeters or inches.

- Plating & material: Nickel vs gold. For instance, TEJTE’s SMA-KKY dual female uses gold-plated brass for durability and low loss.

- Torque & QC: State torque expectations (0.45 ± 0.05 N·m) and the inspection method (pull test, continuity, insulation check).

For examples of detailed product listings, browse TEJTE’s RF connector catalog. Each entry shows interface, plating, and test standards, which is exactly the level of detail procurement documents should capture.

Traceability and compliance

Suppliers also need to provide paperwork, especially if assemblies go into regulated systems:

- Batch number for traceability.

- CoC (Certificate of Conformance) confirming the connector meets spec.

- RoHS/REACH declarations for environmental compliance.

- AQL sampling plan (e.g., Level II, 1.0%) to define inspection scope.

Connectors like TEJTE’s SMA-50KY already come with RoHS compliance and a PTFE dielectric rated to 0–6 GHz, making them suitable for telecom, aerospace, or industrial automation. Including these requirements upfront means your supplier won’t skip them.

If you’re dealing with mixed connector types, the SMA adapter ordering guide applies the same principle — clear specs upfront prevent surprises later.

FAQ

How tight should I crimp an SMA ferrule—do you have a hex height tolerance?

For RG316, aim for a ferrule crimp height of 1.30 ± 0.05 mm using a 1.72–2.03 mm hex die. Go too low, and you risk cutting pull strength; too high, and the braid won’t seat firmly. A small variance may seem harmless, but on a test bench it shows up immediately as poor return loss.

What strip lengths work for RG316 vs RG174 when crimping SMA connectors?

- RG316: Jacket 6.0 mm / braid 3.0 mm / dielectric 2.0 mm / pin 1.0 mm.

- RG174: Jacket 6.5 mm / braid 3.0 mm / dielectric 2.5 mm / pin 1.0 mm.

How do I avoid cracking the dielectric while crimping the pin on thin conductors?

Keep blades sharp and avoid nicking the PTFE. Never over-crimp the pin barrel. If possible, use a positioner jig — it keeps the conductor centered and prevents stress on the dielectric.

Is a right-angle SMA tail weaker than a straight tail under pull and bend?

Yes. A straight crimp connector distributes force axially, so it handles pulls better. A SMA right angle connector shifts stress into the bend, which can fatigue the dielectric faster. In practice, if frequent bending is unavoidable, use a short SMA extension cable as a strain-relief.

When should I choose an RP-SMA crimp instead of standard SMA for Wi-Fi gear?

Most consumer Wi-Fi routers ship with RP-SMA female jacks. If you’re connecting external antennas, you’ll need RP-SMA to mate correctly. It’s a regulatory workaround that became a de facto standard in wireless gear. Don’t assume — check the center contact before ordering.

Does one extra adapter hurt more than an extra short jumper in lab setups?

Generally, yes. Cascading two SMA adapters often adds more mismatch than a single 15 cm RG316 jumper. That jumper might cost you a quarter of a dB, but it also saves wear on panel jacks that are expensive to replace.

What quick tests prove my freshly crimped assembly is good (continuity, insulation, pull)?

Check continuity (<10 mΩ), insulation (>500 MΩ), and pull (≥ spec). Give it 10 quick flex cycles and confirm no wobble. These five minutes of testing are worth it — better to fail at the bench than in the field.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.