SMA Cable Planning for RF Links and Antennas

Feb 11,2026

Planning an SMA cable path is one of those RF tasks that looks trivial on paper and quietly turns painful later. The connector is familiar. The impedance is known. Early measurements usually pass. Nothing appears broken.

Then the enclosure gets closed.

Then the antenna moves outdoors.

Then the test setup gets reused by a different engineer.

That’s when margins shrink, numbers drift, and the cable—previously ignored—suddenly becomes “suspicious.” This article treats SMA cable planning as part of RF system design, not a last-minute procurement decision. The focus is on how sma coax cable, sma rf cable, and sma antenna cable choices affect real systems from lab benches to deployed hardware.

If you want a deeper structural breakdown of how these cables are built internally, you can cross-reference this with our more focused guide on SMA coaxial cable structure and selection, but here we stay at the planning level.

Map SMA cable roles across RF labs and field installs

SMA cable basics and where it actually lives in a system

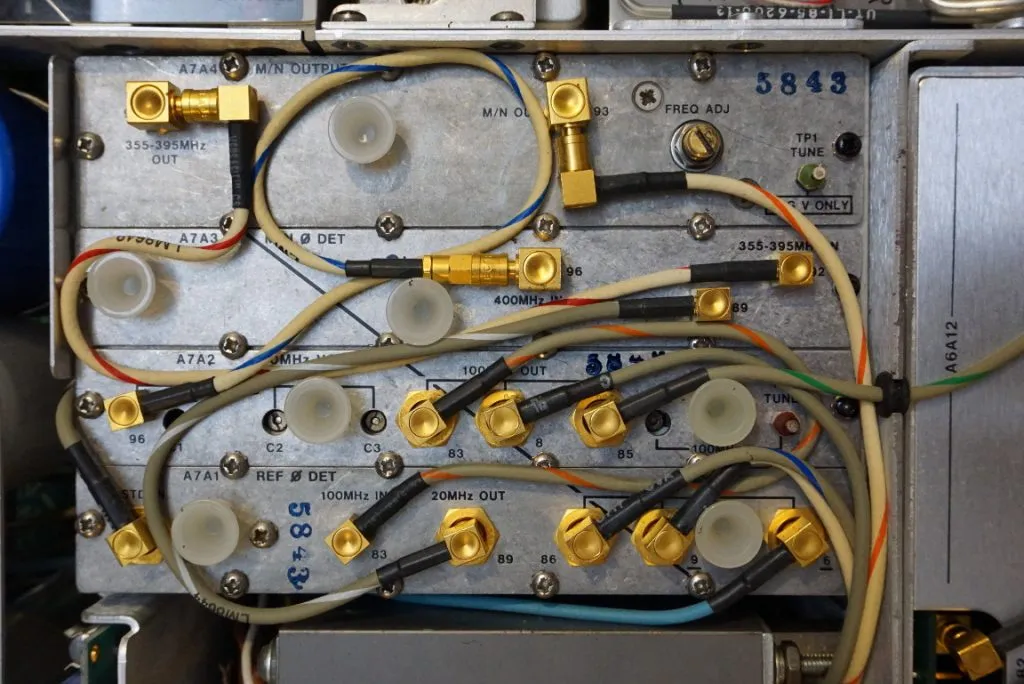

This figure visually anchors the guide’s discussion on SMA cable roles. It depicts three common scenarios: short flexible jumpers on a lab bench, internal links inside a crowded enclosure, and an external antenna cable exposed to the elements. The surrounding text emphasizes that these roles have very different mechanical and environmental demands, and treating them as interchangeable “just SMA cables” is a frequent source of late‑stage margin loss. The image helps engineers recognize that cable selection must begin with where and how the cable will actually be used.

An SMA cable almost never exists on its own. It lives between things that move and things that don’t. Between instruments on a bench. Between a PCB and a panel. Between an enclosure and an antenna mast.

Electrically, most assemblies sold as sma cable or sma coax cable are standard 50-ohm coaxial lines terminated with SMA connectors. Mechanically, however, they serve very different roles:

- Short lab jumpers that are constantly bent, swapped, and re-routed

- Internal links inside enclosures where space is tight and access is limited

- External sma antenna cable runs exposed to vibration, weather, or human handling

Treating all of these as “just SMA cables” is where planning breaks down. A flexible lab jumper that behaves well at 2.4 GHz may be a poor permanent feed line. A rugged outdoor cable may introduce unnecessary stiffness and routing problems inside compact hardware.

A useful mental model: the SMA cable is a boundary component. It bridges electrical domains and mechanical environments. Ignoring either side usually costs margin later.

This figure contrasts SMA with BNC, N‑type, and MCX/MMCX paths. BNC is shown in frequent‑mating test setups, N‑type in robust outdoor installations, and MCX in compact board‑level applications. SMA is positioned as the versatile middle ground—compact enough for dense layouts, yet electrically capable into the multi‑gigahertz range. The guide uses this comparison to explain why SMA is ubiquitous, but also why it is often pushed beyond its original design intent. The image makes the trade‑offs visible at a glance.

Distinguish SMA RF cables from BNC, N, and MCX paths

Engineers often lump SMA together with other RF connectors and assume the differences are cosmetic. In practice, connector families imply very different cable roles.

- BNC paths are optimized for frequent connect/disconnect cycles and are common in video and test setups.

- N-type paths favor mechanical robustness and higher power, especially outdoors.

- MCX / MMCX paths shrink size aggressively but sacrifice mechanical forgiveness.

An sma rf cable sits in the middle. It offers good frequency capability, compact size, and wide availability. That balance explains why SMA shows up everywhere—from spectrum analyzers to IoT gateways.

The downside is that SMA often gets pushed into roles it wasn’t optimized for. Long outdoor runs, repeated torque abuse, or heavy adapter stacks all stretch its comfort zone. Planning improves when SMA is chosen deliberately instead of by habit.

Align SMA cable choices with lab, prototype, and production phases

Cable expectations change over time, even if the RF specs don’t.

In RF labs, flexibility and repeatability matter more than absolute loss. Engineers need cables that bend easily, survive handling, and don’t introduce intermittent faults during measurement.

During prototyping, speed often wins. Mixed cable families, temporary adapters, and borrowed jumpers are common—and acceptable—if risks are understood.

In production, tolerance for variation disappears. A consistent sma coaxial cable family, fixed connector genders, and controlled lengths reduce field issues and simplify support.

A pattern seen in many projects: variety is helpful early, but dangerous if it lingers. Locking down SMA cable choices should be part of design freeze, not an afterthought during purchasing.

How do you translate RF requirements into SMA cable specs?

Turn frequency and power into attenuation and voltage margins

RF requirements rarely arrive as cable specifications. Instead, they show up as center frequency, bandwidth, output power, and required link margin. The cable sits downstream of those decisions.

The first translation step is attenuation. Every sma rf cable has a frequency-dependent loss, usually specified in dB per meter. At higher frequencies, even short lengths can consume meaningful margin.

Power adds another layer. Small-diameter cables and connectors have voltage and thermal limits. A path that looks fine at +10 dBm may behave very differently at +30 dBm, especially above a few GHz.

Rather than asking “What SMA cable should I buy?”, a better early question is:

How much loss and stress can this path tolerate before it becomes the weakest link?

Use SMA coaxial cable characteristics for low-noise and high-power paths

Not all sma coaxial cable assemblies behave the same, even when impedance matches. Shielding structure, dielectric material, and outer diameter all influence performance.

- Dense shielding and stable dielectrics reduce leakage and phase noise

- Larger diameters usually lower loss and increase power handling

- Smaller diameters improve routing flexibility but raise attenuation

Noise-sensitive receive paths benefit from predictable impedance and strong shielding. High-power transmit paths demand attention to connector ratings and thermal behavior, not just datasheet loss numbers.

A practical observation from lab work: many “mystery noise” problems disappear when a marginal sma cable is replaced with one that has better mechanical stability, even if the nominal loss is similar.

Define “good enough” specs for general-purpose SMA lab cables

Over-engineering is common in RF labs. Engineers sometimes default to low-loss or phase-stable cables everywhere, assuming more expensive always means better results.

In reality, many lab measurements below a few GHz are limited by calibration, fixtures, or operator handling—not by cable loss. A general-purpose SMA cable that is flexible, mechanically consistent, and reasonably low loss is often “good enough.”

Typical traits of a solid lab cable include:

- Coverage of the intended frequency band with margin

- Short, controlled lengths

- Connectors that tolerate repeated torque without loosening

Save specialty cables for paths that truly demand them. This keeps benches usable and avoids unnecessary stiffness.

Choose between RG316 coaxial cable and other SMA cable families

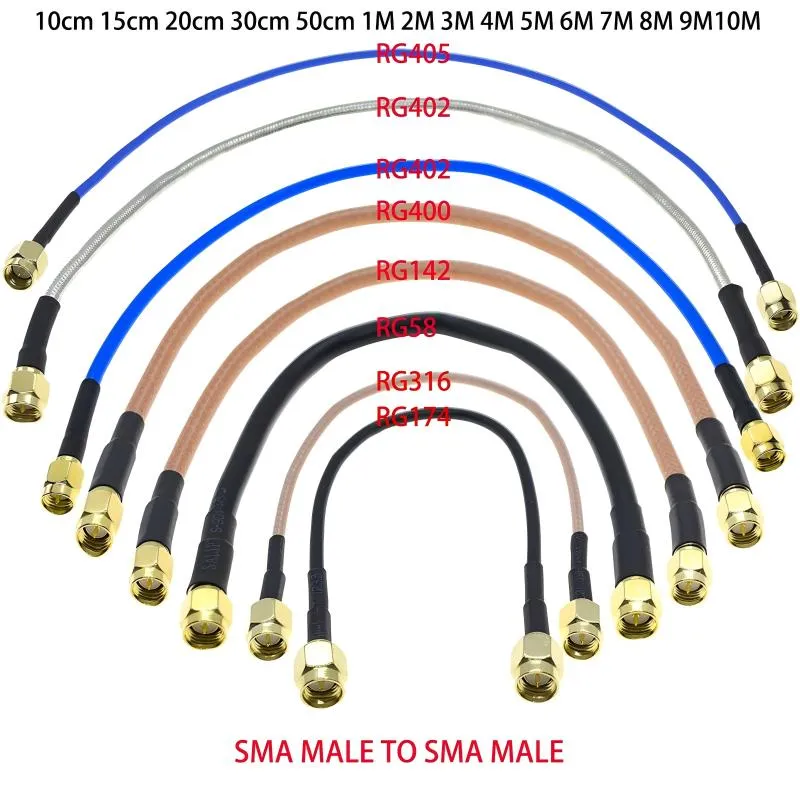

Compare RG316 coaxial cable to RG174, RG58, and low-loss families

This figure presents a typical SMA male to SMA male cable, labeled with the descriptive text “SMA MALE TO SMA MALE”. It is placed within the section comparing RG316 to other cable families (RG174, RG58, low‑loss). The cable shown is likely an RG316 assembly, which the guide describes as the “popular middle ground”—offering better shielding and temperature tolerance than RG174, while being slimmer than RG58. The image serves as a visual reference for the cable type that many labs standardize on for its balanced performance and predictable mechanical behavior.

RG316 coaxial cable sits in a popular middle ground. It offers higher temperature tolerance and better shielding than RG174, while remaining far slimmer than RG58. Loss is higher than true low-loss families, but mechanical robustness often compensates.

A simplified comparison from a planning perspective:

- RG174: very flexible, higher loss, limited thermal performance

- RG316: moderate stiffness, good temperature range, balanced loss

- RG58: bulky, lower loss, better power handling

- Low-loss families: lowest attenuation, highest stiffness and cost

There is no universally “best” choice. The right answer depends on routing space, environment, and acceptable loss—not just frequency.

Match SMA cable outer diameter to routing, bending, and connector options

Outer diameter directly affects real-world usability. Thicker sma cable assemblies demand larger bend radii and restrict connector styles. Right-angle connectors that work well on thin cables may not exist—or may perform poorly—on thicker ones.

Routing constraints often surface late, once enclosures are fixed. Planning cable diameter early avoids awkward compromises like forced bends or stressed connectors.

If your design includes tight internal paths, small diameter may matter more than headline attenuation numbers. This trade-off is easier to manage on paper than in hardware.

Decide when RG316 is worth the extra stiffness in real projects

The stiffness of RG316 coaxial cable is often viewed as a drawback—and in many bench setups, it is. But stiffness is not automatically a negative. In real projects, it can be a signal that the cable is doing something right.

RG316 earns its place when mechanical stability matters more than bend comfort. Automotive systems are a common example. Temperature swings, vibration, and long service life all favor cables with stable dielectrics and tight shielding. Outdoor equipment follows a similar logic. UV exposure, moisture ingress, and mounting stress punish softer cables quickly.

Small enclosures are another case. When an sma cable must hold its shape and avoid collapsing onto sensitive RF traces, extra stiffness can actually improve repeatability. Measurements drift less when the cable geometry stays consistent.

On the other hand, for short lab jumpers or frequently reconfigured setups, RG316 can feel unnecessarily rigid. The takeaway is simple: stiffness is a cost. Pay it only when the environment or reliability requirements justify it.

Design SMA antenna cable runs for length, loss, and environment

Convert link budget needs into SMA antenna cable length limits

An SMA antenna cable directly subtracts from link budget. Instead of asking for a universal “maximum length,” start with allowable loss.

Once you know how many dB the system can afford to lose between radio and antenna, length becomes a derived number. Multiply the cable’s attenuation per meter by length, add connector losses, and compare the result to your margin.

This approach scales cleanly across bands. At 900 MHz, a few meters may be negligible. At 5.8 GHz, the same length can quietly consume the entire margin. Planning based on budget—not rules of thumb—keeps surprises out of late-stage testing.

If you want more detail on how cable length interacts with antenna-side behavior, this planning view pairs well with our dedicated discussion on SMA antenna cable length and loss use cases.

Account for outdoor, automotive, and industrial environments

This figure illustrates SMA antenna cables deployed in three demanding environments: an outdoor mast exposed to sun and rain, an automotive chassis subject to vibration and oil, and an industrial machine with abrasion and dust. The surrounding text stresses that environment often dominates long‑term reliability far more than electrical specifications. The image makes explicit that “SMA antenna cable” is not a single product category—outdoor‑rated jackets, sealed connectors, and robust strain relief are not optional in these contexts. It urges planners to label the environment as part of the cable specification.

Environment changes everything. An sma antenna cable that behaves perfectly indoors can fail quickly once exposed.

Outdoor installations introduce UV radiation, moisture, and temperature cycling. Jackets must resist cracking. Connectors must seal properly. Automotive environments add vibration and oil exposure. Industrial settings bring abrasion, dust, and occasional chemical contact.

These factors rarely show up in RF simulations, yet they dominate long-term reliability. When planning SMA cable paths, it helps to explicitly label the environment: indoor, sheltered outdoor, exposed outdoor, automotive, or industrial. That single word often narrows cable choices faster than frequency does.

Plan grounding and lightning protection around exposed SMA antenna cables

Once an SMA antenna cable leaves the enclosure, grounding becomes part of the RF design. Even low-power systems benefit from clear grounding and surge paths.

The goal is not to turn every installation into a lightning-protected tower, but to avoid floating metal and uncontrolled discharge paths. Proper bonding, grounding points near entry panels, and optional surge arresters protect both equipment and measurements.

This is less about extreme events and more about consistency. A well-grounded cable behaves predictably. An ungrounded one becomes an unknown variable.

For background on connector interfaces and grounding assumptions, the general overview of the SMA connector on Wikipedia provides helpful historical and mechanical context without going into product-specific detail.

How should you route SMA coax cable through enclosures and panels?

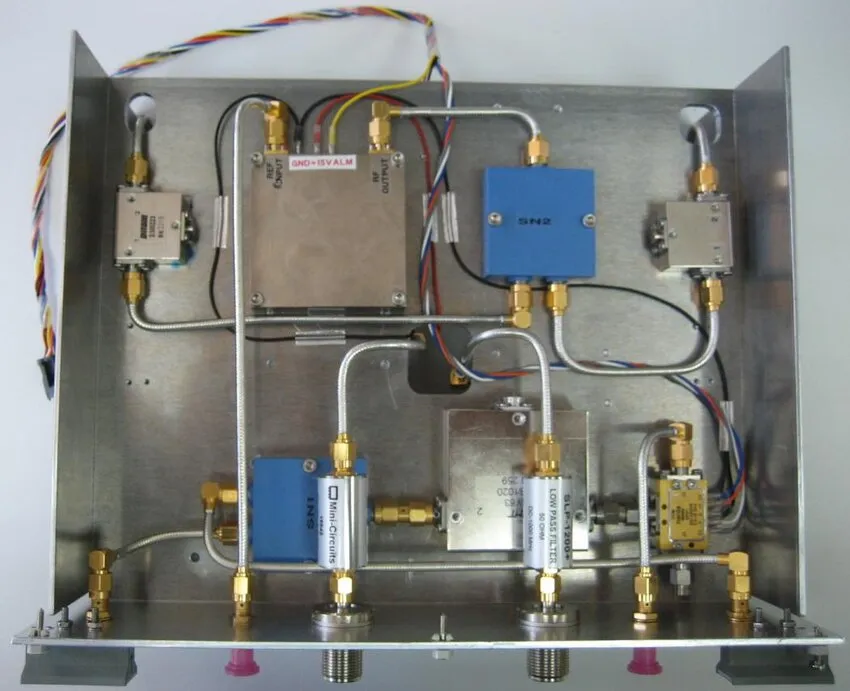

Keep SMA coaxial cable runs mechanically stable but serviceable

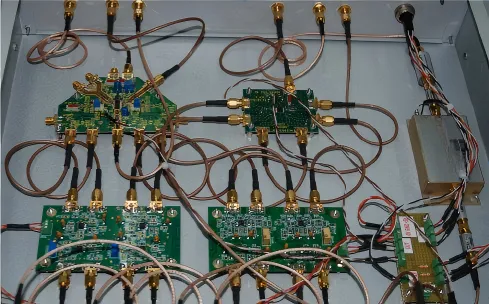

This figure depicts a best‑practice example of SMA coaxial cable routing inside an enclosure. Cables are secured with clamps along their length, preventing movement and mechanical stress on connectors. Near each SMA connector, a gentle service loop provides slack, allowing the connector to be unmated without forcing the cable to bend sharply or twist. The accompanying text warns against routing that is “too clean” with no allowance for movement, which leads to intermittent faults over time. The image translates this practical wisdom into a clear visual guideline.

Inside an enclosure, sma coaxial cable routing is a balancing act. Too loose, and cables wander into sensitive areas. Too tight, and connectors carry constant stress.

A practical approach is staged restraint. Use clamps or tie points to define the cable’s path, but leave small service loops near connectors. This allows disconnection and rework without forcing the cable to twist or bend sharply.

Experienced teams often learn this the hard way. Many intermittent RF issues trace back to cables that were routed “cleanly” but left no room for movement.

Avoid sharp bends and stacking errors in dense RF enclosures

Minimum bend radius is not a suggestion. Sharp bends distort impedance and accelerate mechanical wear. In dense RF enclosures, it’s tempting to fold sma cable assemblies tightly just to make things fit.

Stacking multiple RF lines together creates another issue: coupling. Even well-shielded sma coaxial cable can interact when pressed tightly in parallel over distance. Spacing and routing discipline reduce this risk.

A useful habit is to review cable routing the same way you review RF trace layout. If it looks aggressive on a PCB, it’s probably aggressive in a harness too.

Use panel-mount bulkhead SMA connectors to decouple stress

Panel-mount bulkhead SMA connectors are often overlooked during early layout. They deserve more attention.

By terminating the SMA cable at the panel, mechanical stress is transferred to the enclosure instead of the PCB or cable itself. This is especially valuable for connectors that see repeated mating cycles or external cable movement.

In practice, bulkheads act as mechanical fuses. They isolate delicate internal cables from handling abuse. For systems that ship, get installed, and then get serviced years later, this small design choice pays off disproportionately.

For readers interested in broader connector system planning, this routing discussion complements the higher-level perspective in our RF connector guide for cables, antennas, and test systems.

Standardize SMA cable interfaces, genders, and adapters

Build a consistent rule set for SMA male and female ports

Most SMA adapter problems are not RF problems. They’re workflow problems.

Someone chooses SMA female on a board because that’s what the footprint library had. Another engineer expects SMA male on the panel because that’s what the lab cables terminate in. A third person solves the mismatch with adapters. No one feels wrong—until the system starts accumulating little metal towers of transitions.

A consistent rule set avoids this. Decide, early, where SMA male lives and where SMA female is mandatory. Apply it everywhere: boards, panels, test fixtures, and field cables. Once that rule exists, SMA cable planning becomes predictable instead of reactive.

The RF benefit is modest.

The operational benefit is huge.

Reserve SMA male to SMA female cable extensions for planned cases

An sma male to sma female cable is a legitimate tool. It solves reach problems. It creates clearance. It helps during debug when hardware isn’t final.

The mistake is letting it become permanent without noticing.

Every extension adds another connector pair. That means more insertion loss, more VSWR contribution, and another mechanical interface that can loosen over time. Individually, these effects are small. In combination, they stop being small.

A simple habit helps: if the same extension keeps showing up in the same place, redesign the base sma coaxial cable instead. Treat extensions as temporary by default, permanent only by decision.

Limit adapter stacks between SMA and other connectors

Adapters are convenient. That’s why they spread.

One SMA-to-BNC adapter rarely causes trouble. Two may still be fine. Beyond that, problems stop being theoretical. The stack gets tall. Torque gets awkward. Mechanical stress concentrates in one place.

From an RF perspective, each transition adds mismatch and loss. From a mechanical perspective, stacked adapters behave like levers. Neither effect shows up in a schematic.

If your system routinely needs multiple SMA-to-N or SMA-to-MCX transitions, it’s usually a sign that the SMA cable itself should be rethought, not patched.

Use SMA cable test checks to keep RF measurements honest

Build a quick acceptance test for new SMA RF cables

Not every sma rf cable needs a full datasheet verification. But every new cable deserves a basic sanity check.

Most labs settle on a simple routine:

- Look at the connectors closely

- Check continuity and shield integrity

- Flex the cable gently while watching the measurement

- Run a quick S11 or S21 sweep if the setup allows

This takes minutes. It catches bent center pins, loose crimps, and shipping damage before the cable becomes “trusted.”

Detect intermittent faults caused by flexing and connector wear

Intermittent RF faults are the worst kind. They vanish when you stop touching the cable.

Many of them come from worn SMA connectors or internal shield breaks that only show up under movement. The fix is not fancy instrumentation. It’s motion.

Measure while moving the cable. Rotate the connector slightly. Watch for jumps. If the result changes when nothing else does, the cable has already told you the truth.

In practice, replacing a questionable SMA cable often restores measurement confidence faster than recalibrating everything else.

Schedule periodic retests for frequently used lab SMA cables

Cables don’t fail loudly. They drift.

A lab jumper that looked fine last year may now add an extra fraction of a dB. Another may behave differently depending on how it’s bent. None of this triggers alarms.

Teams that care about repeatability schedule periodic checks for heavily used sma cable assemblies. Quarterly is common. Marginal cables are retired instead of compensated for.

This habit prevents slow erosion of trust in the measurement setup.

Track SMA cable trends in 5G, IoT, and test equipment

Follow how private 5G and IoT gateways still rely on SMA connectors

Despite all the talk of newer RF interfaces, SMA cable assemblies are still everywhere in private 5G nodes and IoT gateways. The reasons are boring—and that’s why they matter.

SMA is small. It’s familiar. It works well enough below millimeter-wave frequencies. Supply chains understand it. Installers expect it.

That combination keeps SMA relevant long after more exotic options exist.

Understand new low-loss and phase-stable SMA coax cable offerings

What has changed is the cable itself. More sma coax cable options now emphasize phase stability and thermal consistency rather than just attenuation.

These cables show up in MIMO calibration, phased arrays, and test environments where small phase shifts matter. They are not universal upgrades. They are targeted tools.

Using them everywhere rarely helps. Using them where phase repeatability matters often does.

Anticipate how higher frequencies push SMA cable closer to its limits

As operating frequencies climb past 6 GHz, SMA stops feeling forgiving. Loss increases quickly. Connector repeatability becomes visible. Small mechanical inconsistencies matter more.

This is where designers start evaluating alternatives like 2.92 mm interfaces. The transition is gradual, not binary, but planning should acknowledge the edge.

Background material on SMA geometry and interface assumptions is summarized well in the general SMA connector overview on Wikipedia, which provides historical and dimensional context without vendor bias.

Apply an SMA cable selection scorecard to your next project

SMA Cable Selection Scorecard

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Project_ID | Project or product name |

| Band_GHz | Operating center frequency |

| P_out_dBm | Output power |

| Cable_family | Cable family (e.g. RG316 coaxial cable, RG174, low-loss 195) |

| Cable_length_m | Estimated cable length |

| Atten_dB_per_m | Typical attenuation at Band_GHz |

| Conn_count | Number of connector pairs |

| Conn_loss_dB_per_pair | Typical loss per pair (0.1–0.2 dB) |

| Env_factor | Indoor = 0; Industrial = 0.05; Automotive/Outdoor = 0.1; Harsh = 0.2 |

| Loss_total_dB | Total path loss |

| Required_margin_dB | Required system margin |

| Margin_actual_dB | Remaining margin |

| Risk_score | Normalized risk score (0–1) |

| Recommendation | Design action |

Core calculations

- Loss_total_dB ≈ Atten_dB_per_m × Cable_length_m + Conn_count × Conn_loss_dB_per_pair

- Margin_actual_dB = Required_margin_dB − Loss_total_dB − (Env_factor × 3)

- Risk_score = min(1, max(0, (Required_margin_dB − Margin_actual_dB) / Required_margin_dB))

Interpretation

- Risk_score < 0.3 → cable choice is unlikely to limit the system

- 0.3–0.7 → monitor; consider shorter runs or a different family

- ≥ 0.7 → redesign recommended

Define the inputs you can estimate early

Use the scorecard to compare SMA cable families

Set team-wide thresholds

FAQ

How long can an SMA cable run at 2.4 GHz before loss becomes a problem?

There is no single length. Start from allowable loss and work backward using the cable’s attenuation.

Can I mix RG316 coaxial cable and cheaper SMA cables in one system?

Yes, but total loss and mechanical behavior must be evaluated together.

Is “SMA RF cable” different from “SMA coax cable”?

In most datasheets, no. The terms usually describe the same 50-ohm assemblies.

When should I switch to low-loss or phase-stable SMA cables?

When frequency, length, or phase repeatability becomes a limiting factor.

Are SMA antenna cables automatically outdoor-rated?

No. Jacket material and sealing determine weather resistance, not the connector.

What quick checks help verify an SMA cable before measurements?

Visual inspection, continuity, gentle flexing, and a basic S-parameter sweep.

Is stacking many SMA adapters safe?

A small number may work. Larger stacks increase loss and mechanical risk and usually justify redesign.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.