SMA Coaxial Cable Structure & Selection

Jan 23,2025

This image appears at the beginning to visually introduce the core dilemma—the SMA coaxial cable often becomes a problem source due to its underestimated timing and role. It might be presented as a project timeline or mind map: the left side lists and highlights early-decided “main drivers” like “RF chip,” “antenna selection,” “enclosure layout”; on the right or at the end, an icon of an “SMA coaxial cable” is placed in a later box, possibly labeled “afterthought” or “default choice.” An overlay of a downward-trending performance curve or increasing error bars might暗示 performance “drift” or margin reduction due to poor cable selection. This echoes the text: “On paper, the cable looks passive… small compromises quietly eat into margin.”

Where does an sma coaxial cable actually sit in your RF link?

Following the subheading “Where does an sma coaxial cable actually sit in your RF link?” this should be a clear system architecture block diagram. The diagram might divide the system into three “domains” represented by dashed boxes: PCB/RF Module Domain (containing chips and internal traces), Enclosure Interface Domain (containing bulkhead connectors), and External Environment Domain (containing antenna or test equipment). An SMA coaxial cable is drawn as the central physical link connecting these three domains, specially highlighted or bolded. Annotations like “Transition Layer” or “Impedance Continuity / Mechanical Stress Absorption” might be placed next to the cable, with arrows示意 signal flow and potential mechanical stress paths. This image visually demonstrates the cable’s role as a critical interface component.

Separate sma cable, sma coax cable and sma rf cable in real usage

Relate sma coaxial cable to rg316 coaxial cable and other 50-ohm families

Decide when sma coaxial cable is the right layer between PCB and antenna

Following the subheading “Decide when sma coaxial cable is the right layer between PCB and antenna,” this is likely a side-by-side comparison. Left Scenario: Shows a typical product interior view: an RF module on a PCB connects via a short SMA coaxial cable to a panel-mount SMA connector, which then connects to an external antenna. This scene might be labeled “Suitable: Modular, Testable, External Antenna”. Right Scenario: Shows a highly integrated device where the antenna element is printed directly on the PCB edge or is a chip antenna, connected to the RF chip via a microstrip line or direct connection. This scene might be labeled “Better: Space-Constrained, Fixed Path, High Integration”. The comparison aims to emphasize that cable use should be based on clear interface needs, not habit.

How do you read sma coaxial cable construction from a datasheet?

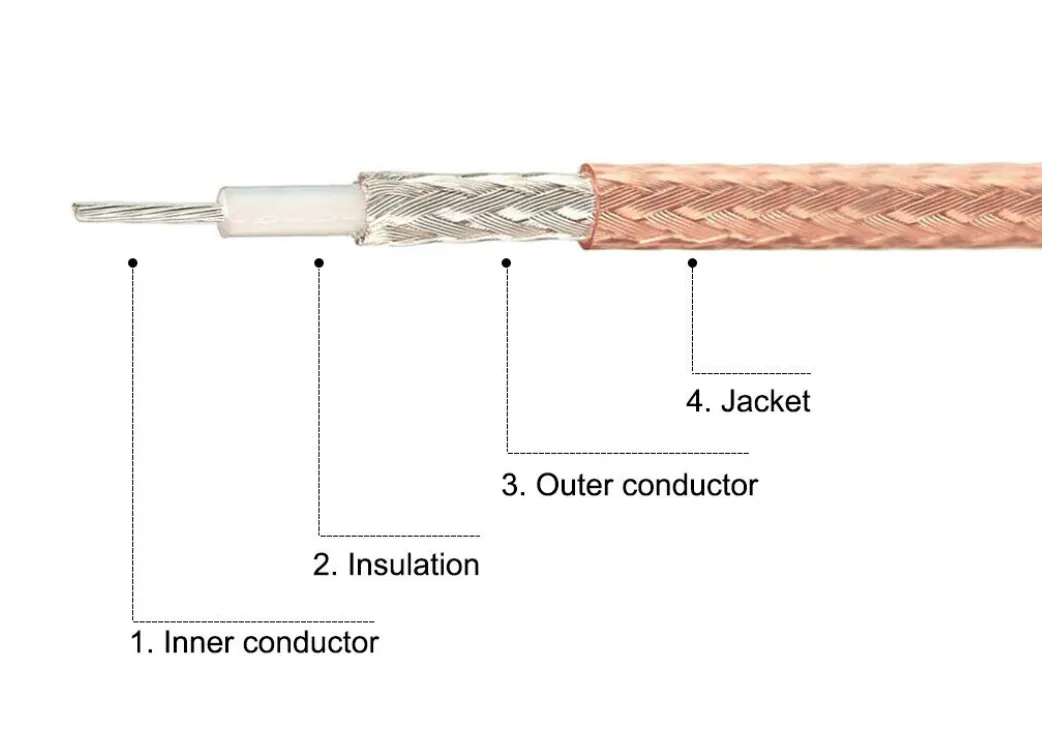

Break down inner conductor, dielectric, shielding and jacket step by step

This is an extension or variant of the structural diagram in Figure 4 or Figure 6, but with a greater focus on field failure mechanisms. It likely uses a vertically arranged exploded view, showing the four layers of RG316 from top to bottom or with arrow indicators: 1) Inner Conductor, 2) Insulation/Dielectric (PTFE), 3) Outer Conductor (Braid Shield), 4) Jacket (FEP). Beside each layer, there might be brief text explaining its primary function and how failure can initiate under stresses like overheating, excessive bending, vibration, or chemical exposure (e.g., excessive bending stresses the dielectric; vibration fatigues the braid; chemical exposure weakens the jacket). This diagram visually explains that RG316 reliability is “layered,” field failures usually begin in one layer and propagate, and the overlap of multiple stressors (bending, heat, vibration) accelerates degradation—interactions that are hidden by looking only at the headline temperature rating.

Link 50-ohm impedance to sma rf cable compatibility and VSWR

Compare sma coax cable OD and bend radius with rg316 coaxial cable

How can you plan sma coaxial cable loss before you lock the length?

Loss is where many RF designs quietly fail. Not through obvious breakage, but through small compromises that accumulate late in the project. A short sma coaxial cable often looks harmless by itself, yet at higher frequencies even fractions of a decibel can decide whether a link feels robust or fragile. Treating cable loss as something to estimate early, rather than something to measure after assembly, usually prevents painful redesigns.

From a fundamentals standpoint, coaxial cable attenuation is driven by conductor loss, dielectric loss, and frequency-dependent skin effects. These mechanisms are well explained in general RF references such as the overview of coaxial cable. What matters in day-to-day engineering work is turning those physical principles into a simple planning habit for sma coaxial cable runs, rather than relying on intuition or rules of thumb.

Define the key inputs for a sma coaxial cable loss planner

Calculate total loss, margin and maximum recommended length

Once the inputs are defined, the calculations are intentionally straightforward. Total cable loss equals attenuation per meter multiplied by planned length. Effective margin equals the original link margin minus that loss. From the same relationship, a maximum recommended length can be derived by dividing the available margin by the attenuation per meter of the selected cable. This logic follows the same principles used in insertion-loss budgeting described in measurement guidance from institutions like the National Institute of Standards and Technology, even though the planner itself remains lightweight.

The outputs are more valuable than the formulas. Total loss shows how much of the RF budget the cable consumes. Effective margin reveals whether the design still has room to breathe. Maximum length creates a hard boundary that helps prevent late-stage decisions that quietly push a design over the edge.

Turn planner results into simple “go / shrink / upgrade” decisions

How should you pair sma coaxial cable with antennas, modules and jumpers?

Connect sma coaxial cable segments to external sma antenna cable wisely

Following the subheading “Connect sma coaxial cable segments to external sma antenna cable wisely,” this should be a system-level connection diagram showing the complete path from source to radiation: RF Module -> (Loss: ? dB) -> Internal SMA Coaxial Cable -> (Connector Loss) -> Panel Bulkhead Connector -> (Loss: ? dB) -> External SMA Antenna Cable -> Antenna. Crucially, typical loss values might be annotated below each cable segment (e.g., Internal: 0.5 dB, External: 1.2 dB), with a calculation like “Total Loss = 0.5 + 0.2 + 1.2 = 1.9 dB” next to the overall path. An arrow or highlight might circle the “Internal SMA Coaxial Cable” segment with an annotation: “Optimizing this segment often yields the highest benefit.” This image emphasizes the importance of considering cable selection within the context of a system-level loss budget, not in isolation.

Decide when internal jumpers should be rg316 coaxial cable

Avoid impedance and connector mismatches when mixing sma rf cable with BNC, N, MCX or MMCX

How can you check sma coaxial cable assembly quality without a full RF lab?

Build a visual inspection checklist for sma cable ends

Use basic continuity and isolation tests before RF measurements

Recognize real-world symptoms of a bad sma coaxial cable

What recent industry trends are changing sma coaxial cable decisions?

Finished RF cable assemblies are becoming the default

SMA interfaces continue to define the RF boundary

Standard cable recipes reduce design friction

How can your team turn sma coaxial cable know-how into a repeatable workflow?

Start every design with impedance, frequency, and environment

Create standard sma coaxial cable recipes for common scenarios

Link sma coaxial cable decisions back to existing RF knowledge

Frequently Asked Questions

When does a sma coaxial cable become the bottleneck in an RF link?

It often becomes the bottleneck as frequency increases, cable length grows, or multiple cable segments are chained together. In marginal designs, even short runs can dominate the loss budget.

Is rg316 coaxial cable always the safest choice for sma rf cable runs?

RG316 is a strong default for short, reliable jumpers, but it is not ideal for long runs or higher power. Thicker 50-ohm cables are often more appropriate in those cases.

Can the same sma coaxial cable recipe be reused for lab and production hardware?

Sometimes, but lab cables emphasize flexibility and durability, while production wiring often prioritizes space and routing stability. Separate recipes usually work better.

How should sma coaxial cable choices be documented for reuse?

Short, recipe-style documentation works best. List cable type, length limits, connector pairs, frequency range, and typical loss, and reference related RF cable guidance where appropriate.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.