WiFi Antenna Cable Matching, Length & Routing in Practice

Dec 27,2025

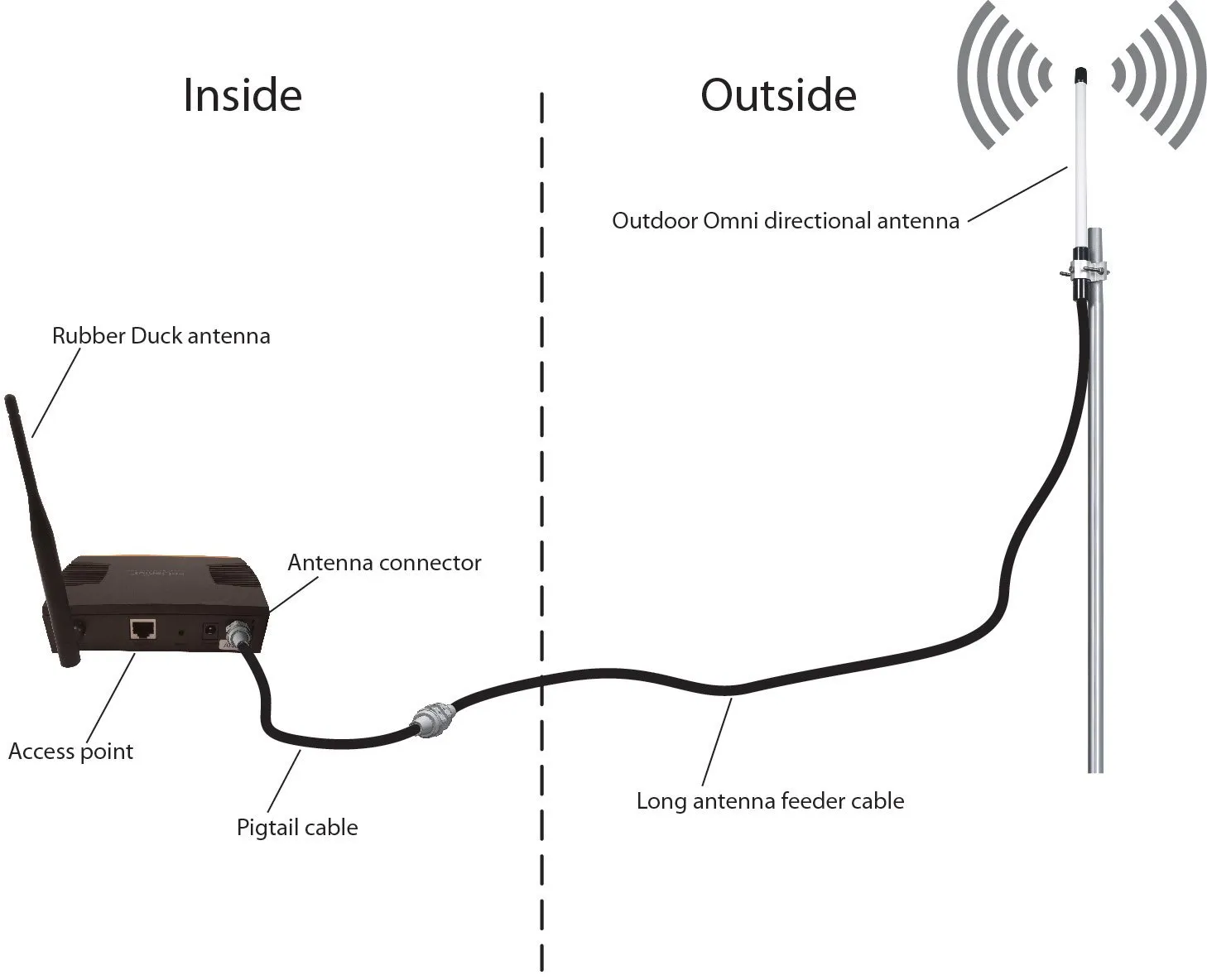

This figure is the introductory schematic at the beginning of the document. It depicts a typical wireless access point deployment scenario: the indoor part (Inside) shows a rubber duck antenna on the device connected via an antenna connector and a signal cable; the outdoor part (Outside) shows a connection to an outdoor omnidirectional antenna via a long antenna feeder cable. The figure visually introduces the document’s theme—the seemingly simple, often added-later antenna cable is a key detail that determines the performance stability of a product in real Wi-Fi systems, especially at 5GHz/6GHz.

A wifi antenna cable rarely looks like a design risk. It’s passive, inexpensive, and usually added late in the build. Yet in Wi-Fi systems, especially at 5 GHz and 6 GHz, that short length of coax often decides whether a product feels solid or frustrating.

Most field issues don’t come from bad antennas or radios. They come from small assumptions:

a connector that “should be SMA,” an extension added to clear a metal enclosure, or an adapter used because it was on hand.

This guide focuses on what actually causes trouble in real hardware. Not theory, not catalog definitions—just the matching, length, and routing decisions that keep Wi-Fi links predictable.

Is my jack SMA or RP-SMA—how do I tell in 10 seconds?

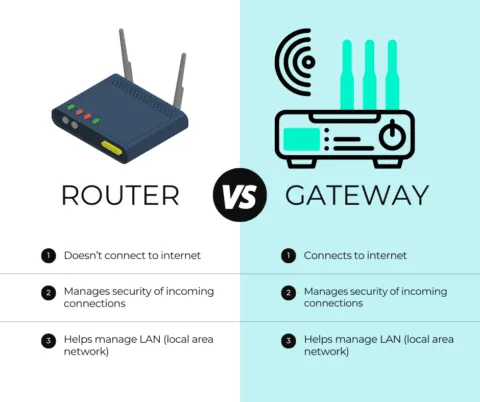

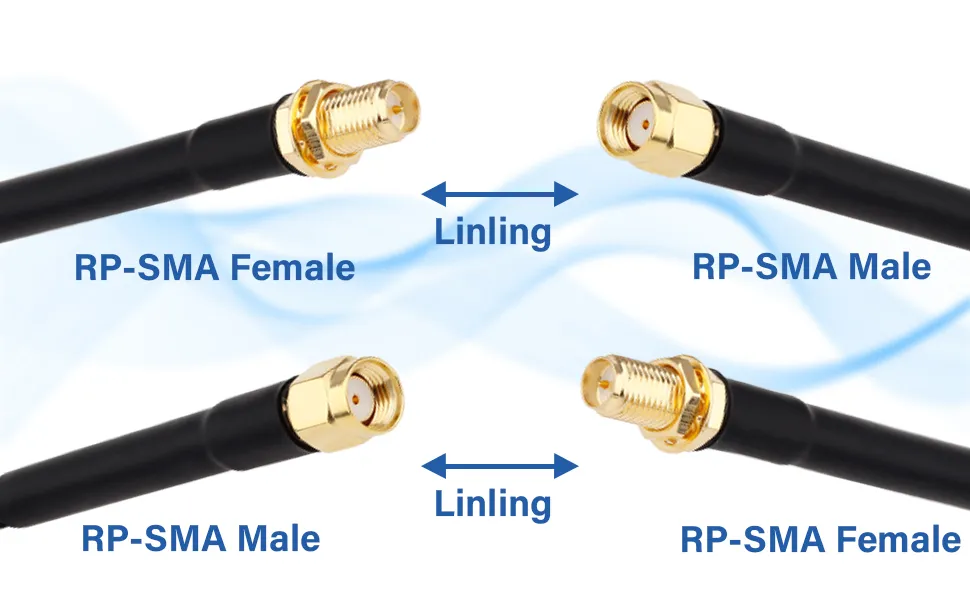

This figure is a core reference for quick and accurate identification of device port types. It juxtaposes four types: SMA female, RP-SMA female, SMA male, and RP-SMA male, providing a direct visual comparison for the reader. Combined with the “Thread X pin/hole quick ID” table below, the figure aims to help users bypass the misleading observation of threads alone. By focusing on the combination of the center conductor (pin or hole) and thread location (internal or external) on the connector face, it allows for unambiguous determination of the actual connector type within 10 seconds, preventing matching errors caused by guesswork or reliance on inaccurate product labels.

If you’ve ever stared at a router port wondering whether it’s SMA or RP-SMA, you’re not alone. The confusion is common because threads are misleading.

The fastest way to identify the port is to ignore names and look directly at the connector face.

Thread × pin/hole quick ID (device vs antenna)

| Center Contact | External Thread | Actual Type |

|---|---|---|

| Pin | Yes | SMA Male |

| Hole | Yes | RP-SMA Male |

| Hole | No (internal thread) | SMA Female |

| Pin | No (internal thread) | RP-SMA Female |

That’s it. Four combinations. No guessing.

This check works for routers, IoT gateways, antennas, and any wifi antenna cable you’re holding in your hand. It’s faster than opening a datasheet and far more reliable than product titles.

A common failure pattern looks like this:

the connector screws on cleanly, torque feels normal, but the link margin collapses. In almost every case, the center contact is mismatched.

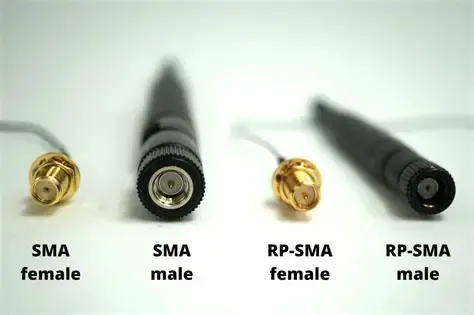

Common router/AP and IoT gateway habits

This figure appears in the section “Common router/AP and IoT gateway habits”. It likely uses a side-by-side illustration or infographic to compare the different trends in connector selection between consumer Wi-Fi routers/access points (often using RP-SMA female jacks) and industrial gateways, radios, or test equipment (more commonly using SMA female jacks). The figure may include icons for “Router” and “Gateway.” It aims to inform readers about industry habits as a reference, but simultaneously emphasizes that these trends are “not guarantees,” as manufacturers may quietly change connectors across revisions, necessitating actual verification before ordering cables.

There are trends worth knowing—just don’t treat them as guarantees.

- Consumer Wi-Fi routers and access points often expose RP-SMA Female jacks

- Industrial gateways, radios, and test equipment more commonly use SMA Female

- Antennas marketed “for routers” are usually RP-SMA Male

Manufacturers change connectors quietly across revisions. Always verify the actual port before ordering cables.

If you want a deeper comparison of connector logic and why these two types coexist, this breakdown of RP-SMA vs SMA is a useful cross-reference.

How do I match both ends of a wifi antenna cable without mistakes?

Male/Female mapping and typical pairs

This figure is a visual guide for the section “How do I match both ends of a wifi antenna cable without mistakes?”. It likely clearly illustrates the four interface types: SMA female, SMA male, RP-SMA female, RP-SMA male, and indicates the correct pairing relationships through connecting lines or labels. For example, an SMA female device port should be paired with an SMA male antenna, and an RP-SMA female router port should be paired with an RP-SMA male antenna. Its core purpose is to translate identified connector types into specific, actionable one-to-one matching rules. It emphasizes the correct workflow of defining the device port first before matching the antenna or cable, and warns against the risks inherent in vague labels like “sma antenna cable.”

Here are combinations that work reliably in the field:

- Router with RP-SMA Female port → antenna with RP-SMA Male

- RP-SMA Male to RP-SMA Female cable

- Gateway with SMA Female port → antenna with SMA Male

- SMA Male to SMA Female cable

Inside enclosures, a short sma male to female cable is commonly used to link a radio module to a panel feed-through. That jumper may only be 10–20 cm, but it still needs the correct gender and connector family.

Be cautious with vague labels like “sma antenna cable.” That phrase alone doesn’t specify:

- SMA vs RP-SMA

- pin vs hole

- which end is which

Spell it out every time.

RP-SMA vs SMA: key differences and mismatch risks

Electrically, SMA and RP-SMA behave the same when correctly paired. The risk is purely mechanical-human.

Mismatches typically lead to:

- Poor return loss and unstable VSWR

- Throughput drops at higher MCS rates

- Inconsistent performance across units

If a Wi-Fi product works on the bench but struggles in the field, connector pairing is one of the first things experienced RF engineers recheck.

How long can I extend before 5/6 GHz range drops?

This figure appears at the beginning of the discussion on extension cable length limitations. It likely uses a simple chart or annotated schematic to visually compare how quickly signal strength or effective range declines with increasing cable length across the 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, and 6 GHz bands. The figure may contain curves or bar graphs representing different frequencies. It aims to visually convey the document’s core point: while short extensions may be forgiving at 2.4 GHz, at 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, the same extension can cause significant performance loss. This leads into the subsequent discussion on when using an extension is justified and how to perform quick loss estimation.

When wifi antenna extension or SMA extension makes sense

A wifi antenna extension cable is justified when:

- The antenna must clear a metal enclosure

- Placement dramatically improves line-of-sight

- The alternative is mounting the antenna in RF shadow

It’s a poor choice when:

- The antenna could be repositioned directly

- You’re already near sensitivity limits

- Multiple adapters are involved

Each connector, each junction, chips away at margin.

Connector and adapter penalty

This figure is a concise visual reminder emphasizing the key concept of the “connector and adapter penalty.” It likely uses a prominent graphic (such as a connector icon labeled “≈ 0.2 dB loss”) or a simple link diagram to intuitively show that each mated RF interface (connector pair) or additional adapter introduces approximately 0.2 dB of insertion loss and reflection effects. Combined with the text below, the figure aims to make readers deeply understand that while the loss from a single interface is small, the cumulative effect of multiple interfaces (especially 2-3) can significantly erode the link budget at 5GHz/6GHz, thereby supporting the document’s recommendations to “avoid unnecessary adapters” and “use extension cables cautiously.”

Field measurements across many builds show a consistent pattern:

- ≈ 0.2 dB loss per connector or adapter

One adapter rarely kills a link. Two or three often do—especially at 5/6 GHz.

Extension Loss Quick Estimator

Inputs

- Frequency: 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz

- Cable length L (meters)

- Number of connectors n

- Adapter present (Y/N)

Estimator

Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency) × L + 0.2 × n

Typical experience-based attenuation (small coax):

- 2.4 GHz ≈ 0.9 dB/m

- 5 GHz ≈ 1.5 dB/m

- 6 GHz ≈ 1.8 dB/m

Outputs

- Estimated total insertion loss

- Suggested length tier: 0.1 / 0.3 / 0.5 / 1 / 2 m

What this means in practice

At 5 GHz and above, once extensions exceed ~1 m with multiple connectors, performance losses become noticeable. In many designs, shortening the run or changing the mounting approach produces better results than extending further.

Do I need a panel feed-through—how do I size an SMA bulkhead?

This figure is a mechanical guidance diagram for the selection and installation of SMA bulkhead connectors. In the form of an exploded view or cross-section, it clearly illustrates the composition of the “stack height” that determines the required connector thread length: starting from the thickness of the mounting panel, adding the internal washer/lock washer, the sealing O-ring or gasket, and the thickness of any external waterproof cap used. The figure aims to correct the common mistake of measuring only the panel thickness, guiding users to perform a complete mechanical stack-up calculation and leave a 1-2 mm margin. This ensures the lock nut has sufficient engagement length and compresses the seal evenly, achieving reliable mechanical fixation and environmental sealing, and preventing later failures due to improper sizing.

Once an antenna leaves the enclosure, you’re no longer just “running a cable.” You’re creating a mechanical interface that has to survive torque, vibration, and time. That’s where an sma bulkhead connector earns its place.

Many teams treat bulkheads as cosmetic hardware. In practice, they’re load-bearing RF components.

Stack height = panel + washer + gasket + cap

The most common bulkhead mistake is measuring only the panel thickness.

What actually matters is the total stack height:

- Panel thickness

- Internal washer or lock washer

- O-ring or gasket

- External sealing cap (if used)

A typical indoor aluminum enclosure might look like this:

- Panel: 1.5 mm

- Washer + O-ring: ~1.5–2 mm

- External allowance: ~1 mm

That puts the real requirement closer to 5 mm of usable thread.

Too short, and the nut barely engages. Too long, and sealing pressure becomes uneven. Neither fails immediately—but both fail eventually.

If you want a deeper dive into mechanical tolerances, sealing, and torque trade-offs, this practical write-up on SMA bulkhead panel drilling and IP67 sealing complements this section well.

2-hole / 4-hole flange vs nut locking

Both styles work. The difference shows up after deployment.

Nut-lock bulkhead

- Faster to assemble

- Lower BOM cost

- Adequate for indoor, low-vibration equipment

Flange-mount (2- or 4-hole)

- Better resistance to rotation

- More consistent gasket compression

- Preferred for mobile, outdoor, or vibration-prone systems

If a device will be shipped frequently or mounted on moving equipment, flanges reduce long-term connector fatigue. That’s not theory—it’s from returned hardware.

What should I use for internal runs: SMA male-to-female cable or SMA antenna cable?

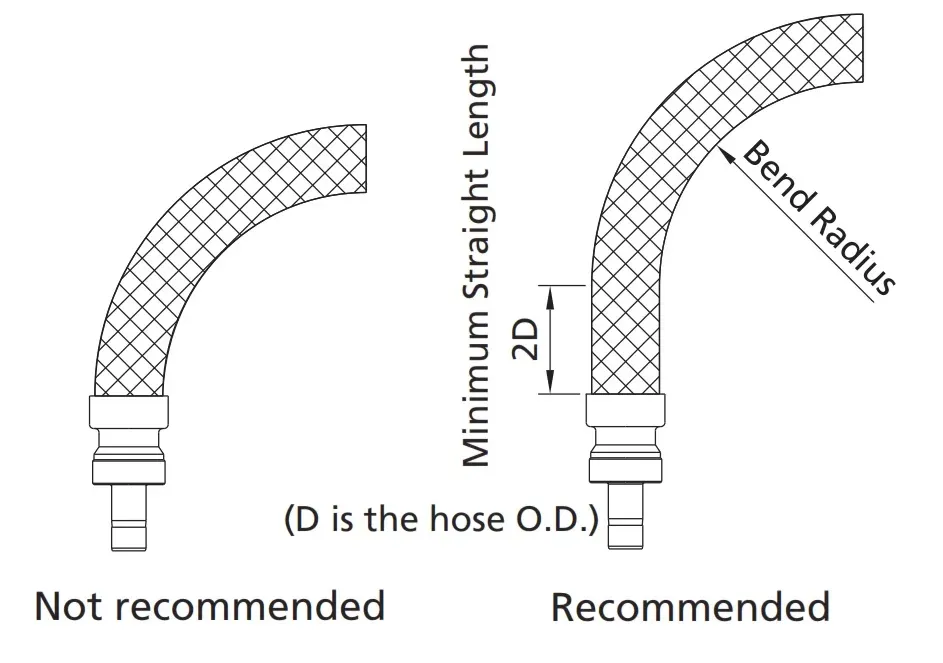

This figure is a visual guide for the routing practices of internal antenna cables (e.g., SMA male-to-female jumpers) within devices. It likely uses a side-by-side comparison of “Recommended” versus “Not recommended” to visually illustrate key principles: the left “Not recommended” side might show sharp cable bends (bend radius less than 10 times the cable outer diameter), direct stress on connections, or lack of securing; the right “Recommended” side shows smooth arc bends (complying with the ≥10x OD rule), using zip ties or clamps for strain relief near connectors, and leaving a small service loop. The figure emphasizes that within internal spaces, mechanical stress often becomes the dominant failure mode, and correct routing habits are crucial for long-term product reliability.

Bend radius, strain relief, and short jumpers

A safe, production-proven rule:

Minimum bend radius ≥ 10× the cable’s outer diameter

Tighter bends often pass initial testing. They fail later, after temperature cycles and vibration.

Short internal jumpers—often sma male to female cable assemblies—should:

- Avoid sharp corners

- Be secured near connectors

- Leave a small service loop where possible

A millimeter of slack beats a connector ripped off the PCB.

EMI, grounding, and routing discipline

Routing matters more than many expect.

Good habits that pay off:

- Keep RF jumpers away from switching regulators

- Avoid running parallel to high-speed digital lines

- Use smooth curves instead of hard angles

When EMI issues appear late in certification, the internal RF jumper is often part of the story—even if it “worked fine” in early prototypes.

Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack—what’s the cost?

This question comes up constantly, especially when inventory is limited.

The honest answer: yes, it works—but it’s rarely free.

Physical compatibility vs RF performance vs compliance

This figure appears in the discussion section “Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack—what’s the cost?”. It likely uses a simple block diagram or infographic to list the three main “costs” introduced by using an adapter: insertion loss, an additional impedance transition, and unit-to-unit variability. The figure may include connector illustrations and arrows representing signal attenuation. It aims to visually support the document’s core argument: adapters solve mechanical compatibility issues but not RF issues; they may be acceptable at low power or with ample link budget, but near sensitivity limits or regulatory thresholds, the introduced loss and reflection can affect link stability and Effective Isotropic Radiated Power (EIRP) compliance, and thus should be used with caution.

Adapters solve mechanical problems. They don’t solve RF ones.

Every adapter adds:

- Insertion loss

- Another impedance transition

- Unit-to-unit variability

At low power, that may not matter. At the edge of link budget or regulatory limits, it often does.

In regulated Wi-Fi systems, added loss sometimes tempts designers to raise conducted power to compensate. That’s where EIRP compliance becomes a concern.

If you’re unsure how connector choice interacts with antenna gain and radiated limits, this overview of antenna gain and radiation basics is a useful refresher.

When adaptation is acceptable—and when it isn’t

Adapters are reasonable when:

- Prototyping or validation

- One-off lab setups

- Very short runs with margin to spare

They’re a poor choice when:

- Shipping volume products

- Operating near sensitivity limits

- Chasing consistent performance across units

When possible, direct connector matching or a shorter cable usually outperforms any adapter stack.

Subtle issues engineers often miss

Not every failure shows up as “no signal.” Many show up as behavior changes.

A few patterns seen repeatedly in the field:

- Throughput instability rather than total drop

- Links that work at 2.4 GHz but struggle at 5 GHz

- Performance variation between otherwise identical units

In many cases, the root cause traces back to connector transitions—often a combination of extension length and adapters that looked harmless on paper.

Why cable decisions age products

One reason wifi antenna cable decisions matter is that they don’t age gracefully.

Radios improve. Firmware evolves. Enclosures stay the same.

A marginal RF path that passes today often becomes the bottleneck tomorrow.

That’s why experienced teams over-spec cable quality and minimize transitions early. It’s cheaper than revisiting mechanical design after deployment.

What belongs on my PO so I avoid returns?

This figure appears in the core chapter “What belongs on my PO so I avoid returns?”. As a product portfolio image, it likely displays, in a neatly arranged manner, the various physical components involved when ordering WiFi antenna cables. This may include cable samples of different lengths and interfaces (e.g., SMA male-to-female, RP-SMA male-to-female), individual SMA and RP-SMA male/female connectors, SMA bulkheads, lock nuts, washers, gaskets, and possibly even adapters. The purpose of this image is to provide readers with a visual reference, linking all the abstract parameters discussed earlier (connector type, gender, need for bulkhead, etc.) to specific physical products. This helps in accurately and unambiguously specifying the required items when completing the purchase order (PO) checklist, fundamentally avoiding returns caused by vague specifications.

If there’s one place where Wi-Fi antenna cable mistakes keep repeating, it’s the purchase order. Not because teams don’t understand connectors, but because details get shortened, implied, or assumed once the project moves fast.

A wifi antenna cable is rarely ordered in isolation. It’s bundled into a larger BOM, reviewed by procurement, then handed to a supplier who has never seen your device. If anything is ambiguous, it will be interpreted—not clarified.

That’s how returns happen.

WiFi Antenna Cable Ordering Checklist

Before releasing a PO, confirm every item below explicitly. If a field feels “obvious,” that’s usually the one that gets misread.

Checklist fields

- Connector family: SMA or RP-SMA

- Center contact at each end: pin or hole

- End configuration: M–F / M–M / F–F

- Cable type (example: RG178, RG316)

- Length (0.1–2 m, state exact value)

- Bulkhead or flange required: Y/N

- Waterproof cap or gasket: Y/N

- Quantity

- Panel thickness and hole diameter (if feed-through)

This list looks basic, but it covers nearly every failure mode seen in the field.

Copy-ready PO note

WiFi antenna cable, RP-SMA male to RP-SMA female, RG178 coax, 0.5 m length.

No adapter. No bulkhead.

Center contact verified. Intended for 5 GHz operation.

That short paragraph removes interpretation. It also makes supplier confirmation much faster.

Teams that standardize this wording tend to stop seeing cable-related RMAs altogether.

Why this checklist matters more at 5 and 6 GHz

At 2.4 GHz, Wi-Fi links often tolerate imperfect cabling. At 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, they don’t. Loss accumulates quietly, and margin disappears long before the link drops completely.

A connector mispair doesn’t always show up as “no signal.” More often, it shows up as:

- Reduced throughput under load

- MCS rates that refuse to hold

- Performance differences between identical units

These issues are expensive to diagnose later. Writing five extra words on a PO is cheaper.

If your design uses bulkheads or enclosure feed-throughs, it’s also worth revisiting mechanical assumptions alongside electrical ones. This is where earlier guidance on SMA bulkhead selection and sealing ties directly into procurement accuracy.

How cable decisions affect long-term product stability

One reason experienced RF teams obsess over cabling is that cable decisions age the product.

Radios improve. Firmware evolves. Antennas get revised.

But enclosure cutouts and cable routing usually don’t change after tooling.

A marginal wifi antenna cable choice that passes validation today often becomes the weak link a year later, when firmware enables higher data rates or additional channels. That’s why conservative choices—shorter runs, fewer adapters, direct connector matching—pay off over time.

It’s not about perfection. It’s about leaving margin.

FAQ — WiFi Antenna Cable

How can I tell if my router jack is RP-SMA connector or SMA connector without opening the case?

How long can a WiFi antenna extension be before 5 or 6 GHz throughput drops noticeably?

What thread length should I choose for an SMA bulkhead on a 1.5 mm aluminum panel with a gasket?

Is a male-to-female SMA extension better than using two adapters back-to-back?

Can I connect an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack and still pass compliance limits?

What bend radius is safe for RG178 in tight enclosures?

Should I strain-relieve the cable behind a panel, and what’s a simple method?

Closing note from the field

This figure accompanies the “Closing note from the field” at the end of the document and is a product application-related image. It is likely a field photograph or simulated scene showing a typical application of a WiFi antenna cable in a real environment. For example, it might show a cable correctly connected to a wireless router’s RP-SMA port with a proper strain relief loop, or depict a short SMA jumper neatly routed from a wireless module to a chassis panel bulkhead in an industrial gateway. The image aims to visually echo and reinforce the point made in the concluding text: the antenna cable is far from a passive accessory; it is an integral part of the RF path, mechanical design, and compliance. When chosen and installed deliberately—as shown in the image, with correct connector matching, tidy routing, and managed stress—it works silently to ensure system stability. Any improper handling, however, can become a performance bottleneck or point of failure. This application image grounds the entire guide’s technical advice into a concrete, successful practice scenario.

A wifi antenna cable is easy to overlook because it’s passive and familiar. In practice, it’s part of the RF path, part of the mechanical design, and part of compliance. When it’s chosen deliberately, nobody notices. When it isn’t, everyone does.

Match connectors visually. Keep extensions honest. Write unambiguous POs.

Those habits don’t just improve performance—they prevent late-stage surprises.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.