RP-SMA Antenna Guide: Router Matching, Gain & Extension

Dec 27,2025

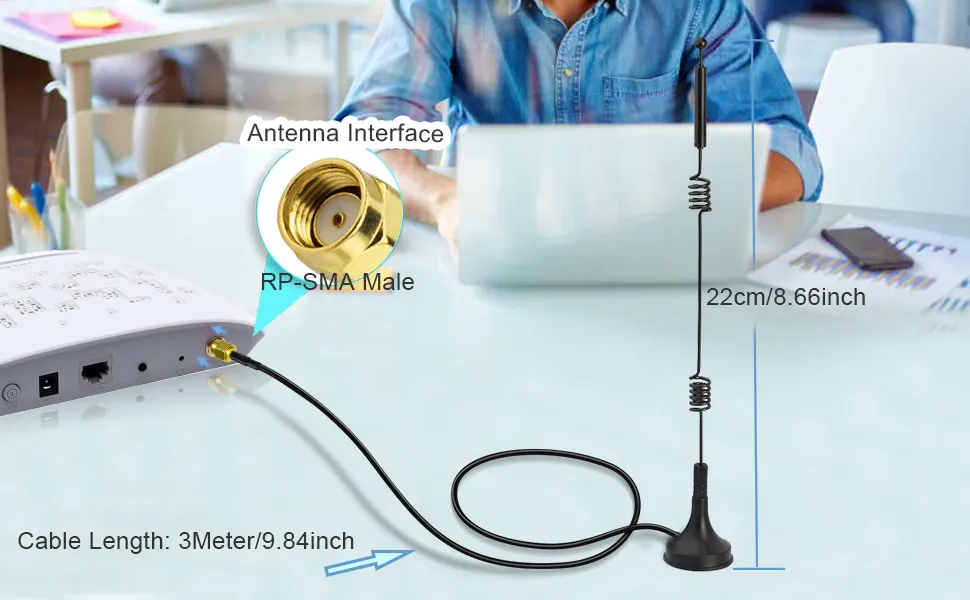

This figure serves as a physical sample at the beginning of the document, showcasing a typical RP-SMA antenna. It clearly labels the connector type (RP-SMA Male), partial cable length (22cm/8.66inch), and total cable length (3Meter/9.84inch). It visually introduces the document’s theme: in real-world deployments, seemingly minor details that are often assumed to be correct (such as connector type and cable length) are frequently the root cause of performance issues.

Routers and access points rarely fail because RF theory was misunderstood. Much more often, they fail because something small was assumed. A connector that looked right. An antenna that screwed on without resistance. A short extension added at the last minute because the enclosure layout changed.

Everything powers up. Throughput even looks fine on day one. Then range feels inconsistent. Higher MCS rates don’t hold. The link drops earlier than expected, especially at 5 GHz or 6 GHz. At that point, the problem is usually blamed on “interference” or “antenna quality,” even though the real cause sits right at the connector.

This article focuses on rp-sma antenna use in real router and access point deployments. Not lab theory, not idealized datasheets, but the checks that actually prevent returns and rework. We’ll talk about connector identification, correct pairing, antenna gain trade-offs, and extension cables—because at modern Wi-Fi frequencies, all of these interact.

If you already understand how coaxial loss scales with frequency and length, you’ll recognize some of the patterns discussed here. If not, the background physics are covered in the RG Cable Guide that many engineers use as a general reference when planning RF cable paths.

Is my router or AP jack RP-SMA or SMA—how do I tell fast?

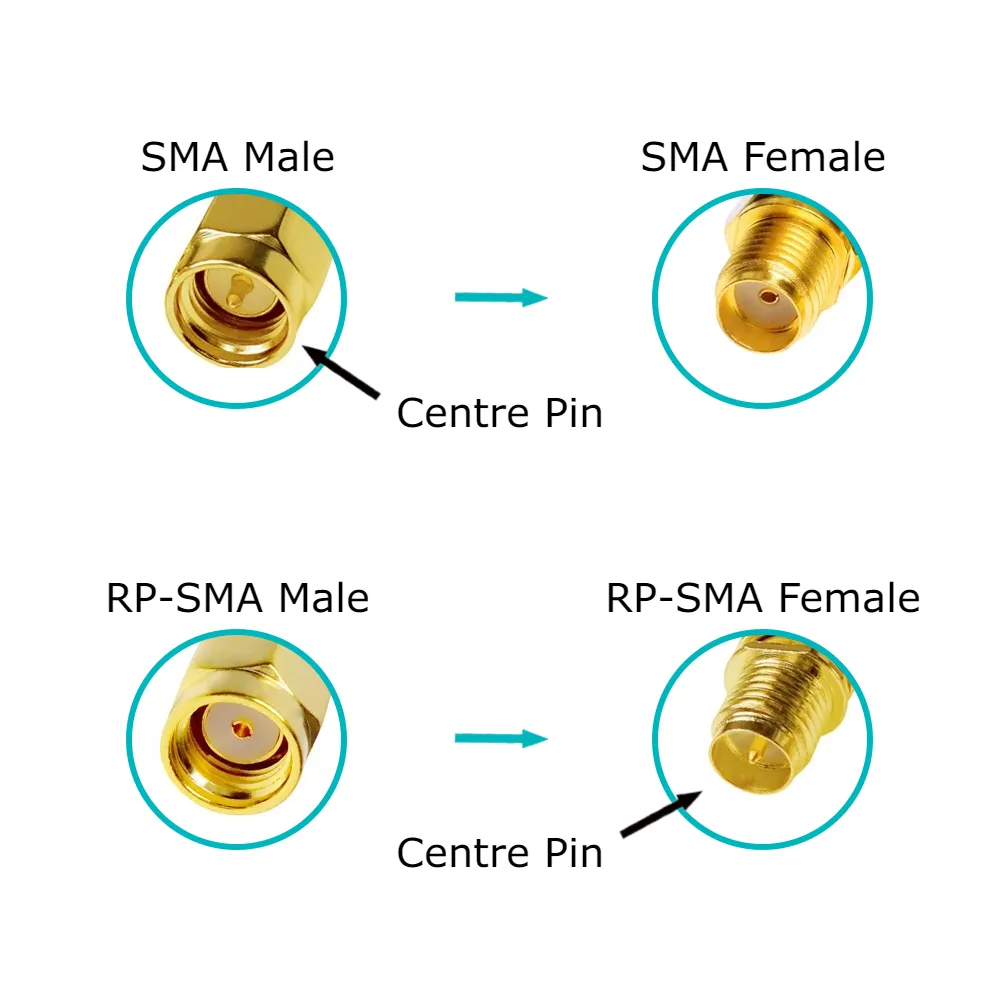

This schematic is a clear visual guide for quickly identifying and differentiating the gender and polarity of SMA and RP-SMA connectors. It compares SMA Male, SMA Female, RP-SMA Male, and RP-SMA Female side-by-side, clearly labeling their thread direction (external or internal) and the state of their center contact (with pin, with socket, hollow). This intuitive comparison is a key tool for avoiding ordering errors and interface mismatches, emphasizing the importance of checking both threads and pins.

Can I identify it in 10 seconds by thread × pin/hole? (device vs antenna)

Yes—if you check both features at the same time.

Start with the threads. External threads indicate a male body, while internal threads indicate a female body. Then look at the center conductor. A visible center pin means a male electrical interface; a recessed socket means female.

Where confusion starts is RP-SMA. The threads are identical to SMA. Only the center contact gender is reversed. That single design choice is responsible for most mismatches seen in the field.

| Interface | Thread location | Center contact |

|---|---|---|

| SMA male | Outside | Pin |

| SMA female | Inside | Socket |

| RP-SMA male | Outside | Socket |

| RP-SMA female | Inside | Pin |

This figure is a key visual reference for connector identification. Through side-by-side comparison, it intuitively reveals the most fundamental physical difference between RP-SMA and SMA connectors: one has a center socket, the other a center pin. Combined with the textual check steps below, it provides a practical method for identification within 10 seconds.

In practical terms, if your router or access point has external threads but no center pin, it is RP-SMA male. That observation alone resolves the majority of cases without any guesswork.

Installers often remember this with a simple rule: threads tell you the body, the pin tells you whether it’s SMA or RP-SMA. It’s not elegant, but it works under pressure.

Common router and AP connector habits—and why they exist

Most consumer Wi-Fi routers use RP-SMA connectors. This convention dates back to early regulatory strategies intended to discourage end users from attaching high-gain antennas that could push radiated power beyond limits. Over time, RP-SMA became the default for consumer gear, even as enforcement models changed.

Industrial gateways and enterprise access points are more likely to use standard SMA connectors. In those environments, antenna choice is controlled as part of the system design, and compliance is handled through documented configurations rather than connector deterrence.

The key point is that brand habits are trends, not guarantees. Models change, revisions happen, and assuming connector type based on product category alone is how mismatches slip through.

How do I match an rp-sma antenna to my device without mistakes?

Male/female mapping and the combinations that actually work

This figure appears in the chapter on “How do I match an rp-sma antenna to my device without mistakes?”. It is a pairing guide diagram, likely showing the correct combination: an RP-SMA male device port should be directly mated with an RP-SMA female antenna. The figure aims to translate the previously identified theoretical knowledge into concrete, actionable connection rules, emphasizing the correct pairing for a direct, low-loss connection and implicitly advising against the use of adapters.

For a direct, low-loss connection, the correct pairings are simple. An RP-SMA male device mates directly with an RP-SMA female antenna, while an SMA female device requires an SMA male antenna. When those conditions are met, no adapter is needed, and the RF path stays clean.

Problems begin when one of those conditions is violated. Common triggers include antenna datasheets that list only “male” or “female” without clarifying the center contact, extension cables ordered in M-M form by default, or adapters added simply because they were available.

There’s a reason experienced RF technicians repeat the same warning: if you didn’t need an adapter, don’t add one. Every additional interface introduces loss, reflection, and mechanical risk, whether or not it shows up immediately in a link test.

RP-SMA vs SMA mismatch—what really goes wrong

A connector mismatch rarely causes a dramatic failure. That’s what makes it dangerous. Instead, it introduces subtle degradation: higher return loss near the radio output, slightly worse VSWR, and reduced margin at higher modulation schemes.

At 2.4 GHz, systems often tolerate these imperfections. At 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, they don’t. Reflections close to the RF front end can destabilize rate adaptation long before RSSI appears problematic. From a regulatory perspective, mismatches also distort the assumed loss budget used to calculate effective radiated power, which matters more as power rules tighten.

If you want a deeper, connector-only comparison focused on physical identification and typical failure modes, this topic is expanded in the dedicated RP-SMA vs SMA identification guide, which many engineers use as a quick cross-check before ordering.

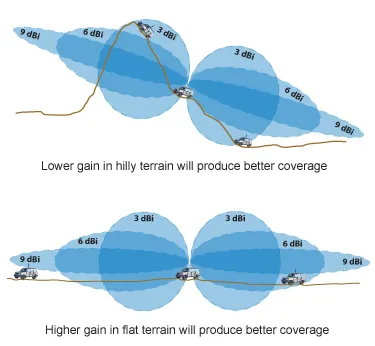

What antenna gain should I pick—how do indoor vs outdoor scenarios differ?

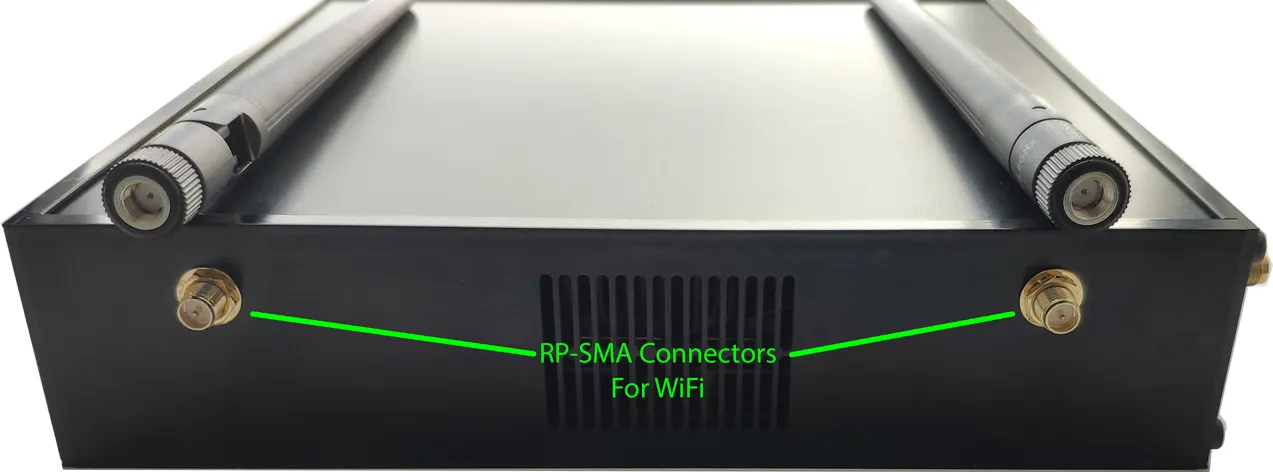

This figure provides a visual explanation of antenna gain selection. It contrasts two scenarios: the left side shows “hilly terrain” with text “Lower gain in hilly terrain will produce better coverage” and a radiation pattern; the right side shows “flat terrain” with text “Higher gain in flat terrain will produce better coverage” and a more focused radiation pattern. The figure intuitively conveys that antenna gain is not “the higher the better,” but rather about the redistribution of energy in space. Selection must be based on the actual deployment environment (terrain, indoor layout) to avoid common coverage misconceptions.

Antenna gain is one of the most misunderstood specs in Wi-Fi hardware. Not because it’s complex, but because it’s easy to oversimplify. Higher gain does not mean “stronger signal everywhere.” It means the same transmit power is redistributed more narrowly in space.

In real deployments, that redistribution can help—or quietly make things worse.

Low, medium, and high gain: what actually changes in coverage

Low-gain antennas in the 2–3 dBi range tend to produce a wide, forgiving radiation pattern. Indoors, this often translates into more consistent near-field coverage, fewer sharp nulls, and better performance when client devices are scattered across rooms at different elevations. Small apartments and single-room offices benefit from this more than most people expect.

Medium-gain antennas around 4–6 dBi flatten the vertical pattern and push energy outward. This is where many corridor deployments, long apartments, and single-floor layouts land. You gain reach without collapsing the vertical lobe too aggressively, which keeps dead zones manageable.

High-gain antennas, typically 7 dBi and above, narrow the vertical beam significantly. In open outdoor environments or long horizontal runs, this is useful. Indoors, it often backfires. Energy overshoots nearby rooms, floors above and below fall into nulls, and roaming behavior becomes erratic.

A common field mistake is installing a high-gain antenna on a desk-level router and then wondering why devices on the same floor but a few meters away perform worse than before. The antenna didn’t fail—the geometry did.

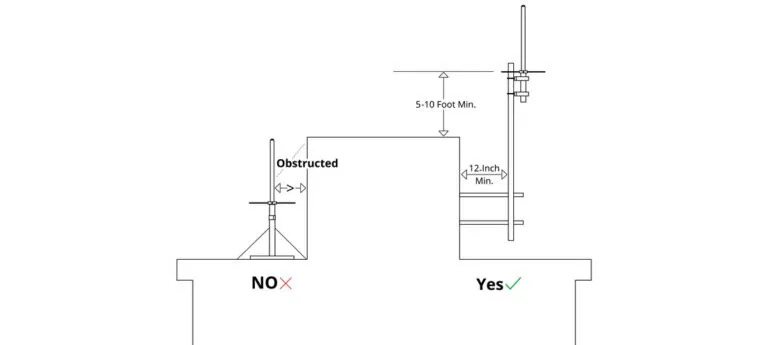

How enclosure edges, metal frames, and springs quietly detune antennas

This figure emphasizes the significant impact of the mechanical installation environment on antenna performance at modern Wi-Fi high frequencies (5/6 GHz). It likely depicts an antenna mounted inside a device, with its radiation field interfered by nearby metal enclosure edges, internal metal frames, or springs, causing its resonant frequency to shift or radiation pattern to distort. The figure visually supports the conservative installation spacing rules given in the document (e.g., keeping at least 10 mm away from large metal surfaces) and explains why short extensions or panel feed-throughs are sometimes needed to reposition the antenna.

At 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, mechanical context matters more than it did in earlier Wi-Fi generations. Antennas that look electrically correct on paper can shift noticeably once mounted near metal.

As a conservative baseline that holds up in production, many RF teams work with the following spacing rules:

- Keep the antenna at least 10 mm away from large metal surfaces

- Maintain 5 mm or more from enclosure edges and bezels

- Avoid running the antenna parallel and close to metal frames

These numbers aren’t magic. They’re empirical. They come from boards that passed validation only after antennas were moved a few millimeters away from a hinge, spring, or ground plane extension. When space is tight, designers often compensate with short extensions or panel feed-throughs—but those introduce their own trade-offs, which leads directly to the next decision.

How long can I extend before 5/6 GHz range drops?

When a Wi-Fi antenna extension cable makes sense—and when it doesn’t

This figure is a detailed specification illustration of an RP-SMA extension cable. It not only shows the physical cable but also clearly labels connector details (RP-SMA male with inner hole, female with inner pin), the coaxial cable model used (low loss RG174), characteristic impedance (50Ω), and length (6ft / 2m). It serves the discussion on “When does a Wi-Fi antenna extension cable make sense,” providing a concrete example of the specific technical parameters that need attention when considering an extension cable, implying that these parameters (cable type, length) will directly impact the link budget.

Short extensions are justified when the antenna needs to clear a metal enclosure, move away from a noisy ground reference, or exit through a panel. They are also common in lab setups and early prototypes.

What tends to cause trouble is using an extension “just for convenience.” A half-meter cable added because the antenna looks nicer on the other side of the router can easily cost more link margin than switching antenna models ever would.

The same logic applies whether you’re dealing with a wifi antenna extension cable, an rp-sma extension cable, or a standard sma extension cable. The physics don’t care about naming conventions.

Connector and adapter penalties you can’t see in the datasheet

Every mated RF interface introduces a small but real penalty. In planning, many engineers use ~0.2 dB per connector pair as a realistic estimate at microwave frequencies. That number includes both insertion loss and the reflection effects that show up once the system is assembled.

Two extra adapters can quietly erase the benefit of a higher-gain antenna. The system still works, but the margin is gone.

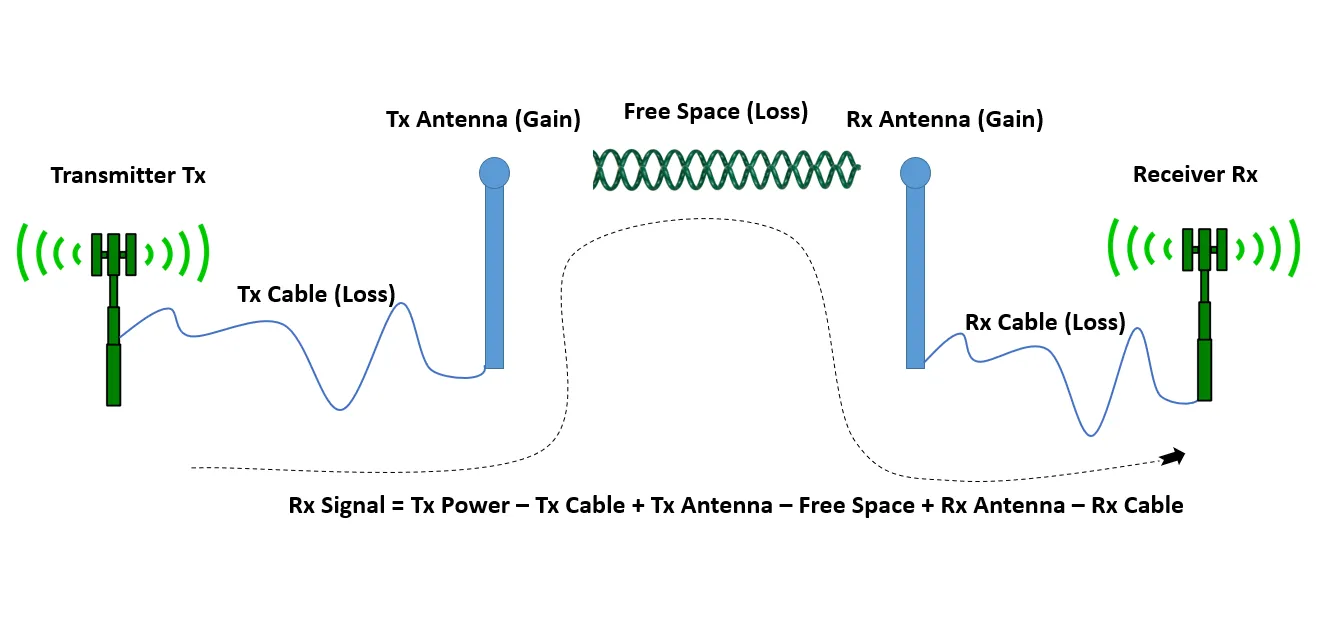

Effective EIRP Estimator

This figure is a system-level link budget calculation model schematic. In block diagram form, it shows the complete process of a signal starting from the transmitter (Tx), passing through transmit cable loss, transmit antenna gain, free-space path loss, receive antenna gain, minus receive cable loss, and finally arriving at the received signal strength. It includes key elements like “Tx Cable (Loss)” and “Rx Cable (Loss).” The figure aims to guide readers toward quantitative analysis rather than guesswork, by incorporating factors such as antenna gain, cable loss, and connector count into a unified estimation model to assess their net impact on Effective Isotropic Radiated Power (EIRP) and the final received signal.

Instead of guessing, it’s more reliable to estimate the net effect of antenna gain, cable loss, and connectors together.

Inputs

- Antenna gain, Gain_ant (dBi)

- Cable type (default: RG178)

- Cable length, L (meters)

- Number of connectors/adapters, n

- Frequency band (2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz)

Loss model

- LineLoss(dB) ≈ α(f) × L + 0.2 × n

- Effective EIRP = P_tx + Gain_ant − LineLoss

Typical RG178 attenuation (rule-of-thumb planning values):

| Frequency | Approx. loss (dB/m) |

|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | ~1.0 |

| 5 GHz | ~1.8 |

| 6 GHz | ~2.2 |

Worked example

A 5 dBi antenna connected through 0.5 m of RG178 with two connectors at 6 GHz results in roughly:

LineLoss ≈ 2.2 × 0.5 + 0.4 ≈ 1.5 dB

In other words, nearly one-third of the antenna’s gain is already gone before considering mismatch or detuning.

Interpretation bands many teams use

- ≤ 1 dB total loss: usually acceptable

- 1–2 dB: reconsider length or connector count

- ≥ 2 dB: redesign the layout or change cable type

Engineers familiar with coax behavior will recognize how quickly these numbers climb with frequency. If not, this is exactly why coax selection and routing are treated as a system problem in guides like the RG cable overview linked earlier.

Do I need a panel feed-through—and how do I size an SMA bulkhead?

How to calculate stack height without guessing

This figure is a guidance diagram for the mechanical installation dimensions of an SMA bulkhead connector. It likely takes the form of an exploded view or cross-section, showing the entire “stack” from the outside of the panel to the lock nut, including the thickness of the panel itself, any washers used, O-ring/gasket, and external weather cap. The figure aims to reframe the selection of a feed-through from an RF problem into a mechanical stack-up problem, emphasizing the reliable method of determining the required connector thread length by summing the thicknesses of all relevant components and adding a 1–2 mm margin to ensure proper engagement and sealing.

The most reliable way to size an sma bulkhead is to treat it as a mechanical stack-up problem, not an RF one. Start with the panel thickness. Add the washer(s), gasket or O-ring, and any external weather cap if used. Then ensure there is still enough thread engagement for the nut to seat fully under torque.

A practical rule many assemblers use is to add 1–2 mm of margin beyond the calculated stack height. Too short and the nut won’t seat. Too long and the O-ring may not compress correctly, compromising sealing. In aluminum panels around 1–2 mm thick, this margin often decides whether a unit passes environmental testing on the first build or comes back for rework.

If you’re planning outdoor or semi-outdoor installs, the mechanical side of this decision matters just as much as RF. Detailed drilling and sealing practices are discussed in the panel-mount workflow covered in SMA Bulkhead Panel Drilling & IP67 Sealing, which many teams reference when enclosure tolerances are tight.

2-hole vs 4-hole flanges: when the difference shows up

Two-hole flange mounts are usually sufficient for indoor equipment where vibration is minimal. They’re quicker to install and occupy less panel area. Four-hole flanges distribute stress more evenly and resist loosening under vibration or thermal cycling. In outdoor APs or equipment mounted on poles or machinery, that difference shows up over time.

The RF behavior is essentially the same. The decision is mechanical longevity and sealing reliability, not signal integrity.

Can I adapt an rp-sma antenna to an sma jack—and what’s the cost?

Physical compatibility is not RF equivalence

An adapter adds another impedance transition, another mechanical interface, and another tolerance stack. At 2.4 GHz, that often goes unnoticed. At 5 and 6 GHz, it becomes measurable. The added insertion loss may be small, but reflections close to the radio output stage affect link stability before RSSI numbers look alarming.

From a compliance standpoint, adapters also complicate assumptions about loss budgets. When effective loss changes, EIRP calculations shift, even if transmit power remains constant.

When adaptation is acceptable—and when it isn’t

This figure visually summarizes the applicable boundaries of adapters. It may use scenario comparisons (e.g., short-term testing vs. long-term outdoor deployment, low-power indoor vs. standard-power 6 GHz design) or risk level classifications to illustrate situations where the additional loss and reflection introduced by an adapter are acceptable (e.g., lab setups, temporary testing) versus those where they are high-risk and should be avoided (e.g., production environments, long-term stable operation, scenarios with strict compliance requirements). The figure echoes the document’s core advice: adapters should be a deliberate choice, not a default convenience.

Using an adapter is generally acceptable for short-term testing, lab setups, or low-power indoor deployments where margin is generous. It becomes risky in outdoor installations, standard-power 6 GHz designs, or any production build expected to remain stable for years.

When possible, replacing the antenna or cable with the correct termination is almost always the cleaner solution. Adapters should be a deliberate choice, not a default convenience.

What belongs on my PO to avoid returns?

Port Identification & Ordering Decision Tree

This figure is a systematic decision flowchart designed to avoid procurement errors. Presented in a tree structure, it starts with input information such as confirming the device port type, then proceeds through a series of logical judgments (e.g., whether an extension is needed, whether a panel feed-through is required, whether waterproofing is needed), ultimately outputting a list of correct component specifications (e.g., antenna interface type, extension cable type, bulkhead specifications, recommended cable length). The figure may include illustrative connector combination diagrams (e.g., SMA male-to-male, SMA male-to-RP-SMA male). It integrates all the previously scattered knowledge points into an actionable checklist, serving as a key tool for generating error-free purchase orders.

Inputs to confirm

- Device port type (SMA or RP-SMA)

- Center contact (pin or socket)

- Antenna interface

- Panel feed-through required (Y/N)

- Extension required (Y/N)

- Desired length (0.1 / 0.3 / 0.5 / 1 / 2 m)

- Waterproofing required (Y/N)

Decision logic

- Match electrical gender first (pin to socket)

- Match body thread second

- Add extension only if mechanically required

- Add bulkhead only if panel exit is required

Outputs

- Correct antenna termination

- Extension cable type (M-F / M-M)

- Bulkhead specification and thread length

- Recommended cable length

Copy-ready PO note

Router port: RP-SMA male (external thread, no pin).

Antenna: RP-SMA female, 5 dBi.

Extension: none required.

Panel feed-through: no.

Install as direct connection; no adapters.

That short paragraph prevents the majority of mismatches seen in fulfillment.

Do Wi-Fi 7 and 6 GHz updates change antenna or extension choices?

6 GHz VLP expansion—why margin matters more now

Recent regulatory updates from the Federal Communications Commission, published via the Federal Register, expand very-low-power operation across the 6 GHz band. This opens more deployment scenarios, especially for portable and indoor equipment, but leaves less room for unaccounted losses and reflections.

In practice, that means connector choice, extension length, and antenna placement matter more—not less—than in earlier Wi-Fi generations.

AFC pilots and enterprise outdoor implications

Standard-power operation under AFC is being validated through enterprise pilots involving companies such as Cisco and Federated Wireless. These deployments place tighter emphasis on documented EIRP budgets, clean RF paths, and mechanically stable installations, particularly for outdoor access points.

The takeaway for designers is straightforward: as regulation becomes more dynamic, assumptions become more expensive.

Frequently asked questions

How can I tell if my router uses RP-SMA or SMA without opening the case?

Check thread location and center contact together. External threads with no center pin indicate RP-SMA male.

What antenna gain should I use in a small apartment versus a long hallway?

Low to medium gain (2–5 dBi) usually performs better in small apartments. Long hallways benefit from moderate gain, but very high gain often creates indoor dead zones.

Will a 0.5 m extension reduce 6 GHz throughput more than 0.3 m?

Yes. At 6 GHz, the additional loss is often enough to reduce margin noticeably, as shown in the EIRP estimator in Batch 2.

Can I connect an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack using an adapter?

Physically yes, electrically with penalties. Adapters add loss and reflection and complicate compliance assumptions.

What bulkhead thread length do I need for a 1.5 mm aluminum panel with a gasket?

Measure the full stack height and add 1–2 mm margin to ensure proper nut engagement and seal compression.

Is RG178 flexible enough for tight enclosures?

Yes, but observe a bend radius of at least 10× the outer diameter to avoid long-term reliability issues.

Do Wi-Fi 7 and 6 GHz changes affect whether I should choose RP-SMA or SMA?

No. Connector type doesn’t change regulatory limits, but tighter margins make correct matching and clean RF paths more important.

Closing perspective

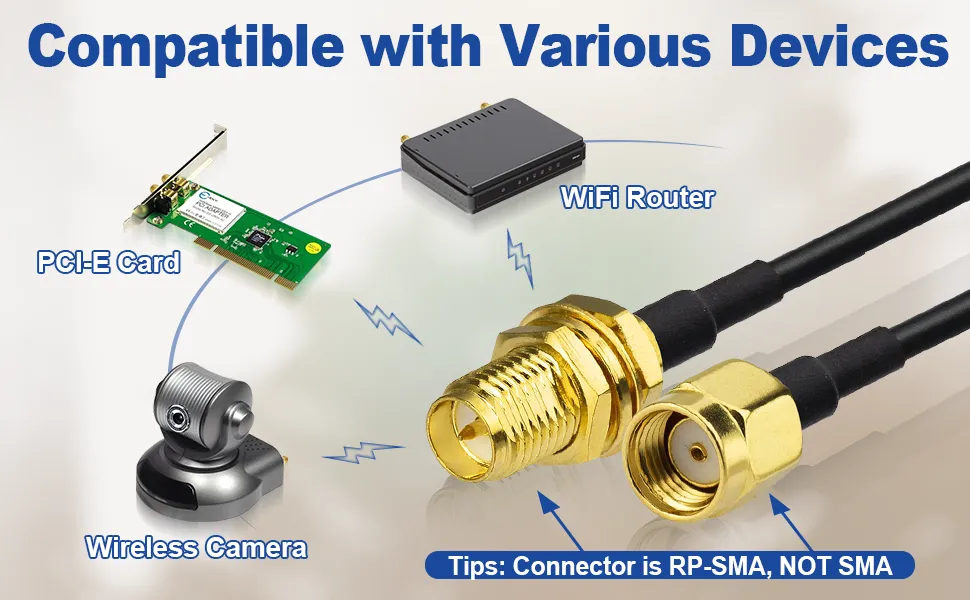

This figure is located in the “Closing perspective” section at the end of the document. It is a compatibility illustration, likely in the form of a collection or scene diagram, showing that RP-SMA antennas can be used with various common wireless devices such as PCIe cards, Wi-Fi routers, and wireless cameras. It prominently repeats the core identification point with “Tips: Connector is RP-SMA, NOT SMA.” The figure aims to reinforce the awareness of RP-SMA as a common standard for consumer-grade Wi-Fi equipment while reminding users to avoid confusion with standard SMA. It echoes the theme from the beginning of the document and emphasizes the overarching concept of treating the antenna path as part of the RF design.

RP-SMA versus SMA isn’t a branding issue. It’s a system detail that affects matching, loss, and long-term stability. Antenna gain, extension length, and connector count all interact, especially at 5 GHz and 6 GHz where tolerance for shortcuts is thin.

If there’s one consistent lesson across deployments, it’s this: treat the antenna path as part of the RF design, not an accessory added at the end.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.