Rubber Duck Antenna Guide: Indoor Coverage, Gain & SMA Match

Dec 16,2025

Located at the beginning of the article, following the core question “Which rubber duck antenna form fits your device and space?”, this image concretizes the discussion about mechanical fit and installation stress in the text through an intuitive comparison of three common forms (straight, right-angle, bendable). It aims to help engineers understand that antenna selection is not just about matching electrical parameters, but also about the mechanical match between physical form, device enclosure space, connector layout, and usage scenarios (e.g., transport stress, routine repositioning). This is the first step in ensuring stable connections in real-world use.

Which rubber duck antenna form fits your device and space?

Pick straight vs right-angle vs bendable whips for tight enclosures

Positioned in the latter part of the guide, this summary image serves as a visual catalog, materializing the textual descriptions into physical products after all key technical parameters and selection points have been introduced. It helps engineers and procurement staff quickly grasp the diversity of products available from TEJTE, echoing the earlier “Ordering Matrix” or SKU list, and acts as a bridge connecting technical selection with final procurement decisions.

A straight rubber duck antenna works best when there’s enough vertical clearance—like routers or access points on open desktops. Right-angle types fit better in compact setups or wall-mounted gear where headroom is limited. If your device sits inside a crowded cabinet, a bendable whip lets you adjust the antenna direction while maintaining the same SMA or RP-SMA interface.

A right-angle model can cut stress on connectors during transport, while a flexible one can survive routine repositioning. The choice isn’t just ergonomic—it’s mechanical insurance. Each bend or angle alters the ground plane coupling, so test both orientations before finalizing your design.

Choose 2/3/5/6 dBi lengths to match desktop/handheld/corridor use

Length and gain walk hand in hand. A 2 dBi antenna offers a rounder radiation pattern—perfect for handhelds and close-range coverage. 3 to 5 dBi works well for desktop routers or gateways placed in open rooms. Go beyond 6 dBi, and you’ll gain more horizontal reach but sacrifice vertical coverage, which can create dead zones above or below the antenna plane.

For corridor-style coverage, 5 dBi is the sweet spot: it extends reach along hallways without introducing severe nulls at ceiling or floor height.

If your product must support both 2.4 GHz and 5/6 GHz Wi-Fi bands, double-check that the antenna is labeled dual-band—many “rubber ducky” antennas in online catalogs claim it but aren’t tuned for both.

How do you tell SMA from RP-SMA in 5 seconds?

Pin vs hole, inner vs outer thread: quick bench checks

This figure is central to the document, designed to help readers distinguish between standard SMA and Reverse Polarity SMA within 30 seconds. It clearly illustrates the four key types (SMA Male/Female, RP-SMA Male/Female) and highlights whether the center conductor is a pin or socket – the most critical factor for identifying polarity and preventing connection failures due to confusion.

Here’s the 5-second rule:

- SMA male → has a center pin and outer threads.

- SMA female → has a center receptacle (hole) and inner threads.

- RP-SMA male → has a hole but outer threads.

- RP-SMA female → has a pin but inner threads.

That reversal (“RP” stands for reverse polarity) was designed to meet FCC regulations years ago but still confuses new engineers. Never assume gender from the thread alone.

If you’re setting up a test bench, label your connectors using a simple color code: red for SMA, blue for RP-SMA. It reduces mix-ups when technicians swap antennas during validation.

For a more detailed comparison between SMA families, check SMA vs RP-SMA check on TEJTE’s blog—it outlines the mechanical and frequency limits of each style.

Labeling and color coding that prevent lab mix-ups

A small dab of paint or heat-shrink tubing on connectors prevents future confusion. In production lines, TEJTE recommends printing connector types directly on pigtail labels—“SMA-M,” “RP-SMA-F,” etc.—to eliminate rework. This becomes essential when both interface types appear on the same PCB for dual-band systems or regional variants.

Consistency matters. Even one mislabeled lot can lead to hundreds of field returns, especially if devices require 5 GHz high-gain omni antennas for regulatory testing.

Will a 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi rubber-duck meet your coverage target?

2.4 GHz vs 5/6 GHz expectations indoors; corridor vs open office

At 2.4 GHz, typical indoor path loss hovers around 4–6 dB per wall and about 60–70 dB across an average office. At 5 GHz, expect roughly 8–10 dB higher loss for the same layout, and 6 GHz climbs even faster. That’s why many integrators still choose rubber duck antennas for IoT base stations even in dual-band designs.

In a corridor, high-gain omnis (5–6 dBi) may look appealing, but they often overshoot ceiling-mounted devices. Conversely, low-gain models maintain smoother coverage gradients—less “ping-ponging” between APs. It’s always about trade-offs: gain increases range but narrows elevation lobes.

“High-gain omni” trade-offs: elevation nulls and dead-zone risks

A high-gain omnidirectional antenna compresses its vertical beamwidth, forming a flat donut pattern. While that extends horizontal reach, it also introduces “elevation nulls” above and below the main lobe. If your antenna sits close to users (like on a handheld), that’s bad news—signal strength can swing dramatically just by tilting the device.

Real-world measurements show that a 6 dBi rubber duck can create as much as 10 dB null depth directly above the antenna, enough to break video streams. That’s why TEJTE’s omni coverage optimization guide emphasizes measuring coverage at multiple heights, not just distances.

What cable and adapter choices quietly erase (or save) your link margin?

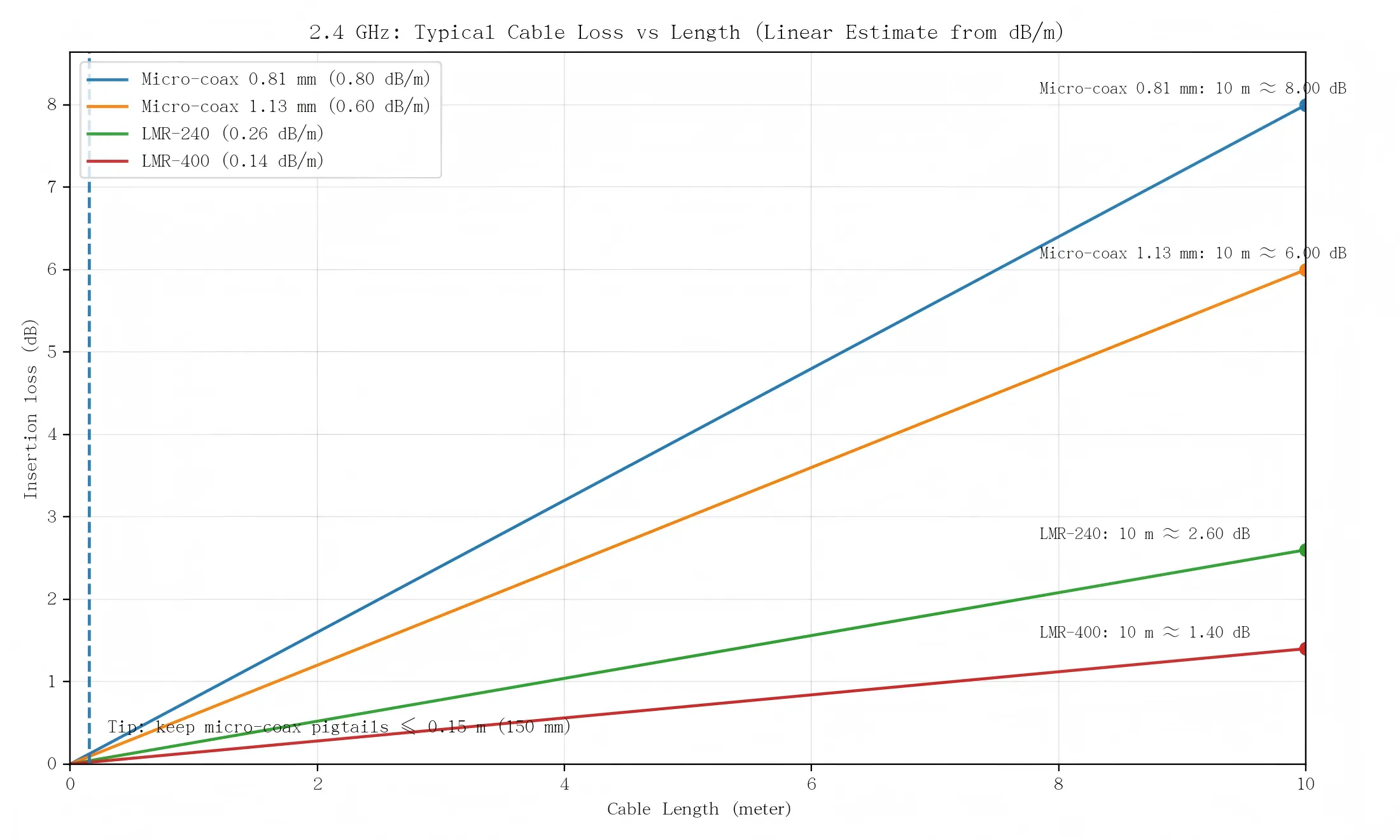

Micro-coax 0.81/1.13 vs LMR-240/400 loss @ 2.4 GHz; keep pigtails short

This image is positioned in the crucial chapter “What cable and adapter choices quietly erase (or save) your link margin?”. It visualizes the attenuation coefficients of different cables, directly supporting the argument that “cables are silent killers of link budget.” The chart clearly reveals the loss difference between micro-coax cables (0.81mm, 1.13mm) commonly used in small devices and the better-performing but bulkier low-loss cables (LMR series). It provides quantitative decision-making basis for engineers when selecting cable types and limiting pigtail length (e.g., “keep internal pigtails below 150 mm whenever possible”) during design, serving as an indispensable reference for optimizing overall RF performance.

At 2.4 GHz, approximate attenuation is:

- 0.81 mm coax → 0.8 dB/m

- 1.13 mm coax → 0.6 dB/m

- LMR-240 → 0.26 dB/m

- LMR-400 → 0.14 dB/m

Shorter is better. Every additional meter of micro-coax can cost 0.5–1 dB. In practice, keep internal pigtails below 150 mm (6 inches) whenever possible. Use bulkhead-mount SMA connectors to minimize bends and stress points.

If you’re routing through metal panels, consider LMR-240-UF (ultra-flex) or RG-316 with proper strain relief. TEJTE’s omni coverage optimization post explains how to factor cable loss into EIRP compliance.

Count connector pairs; VSWR/return-loss near antenna + enclosure

Each connector pair (male + female) adds roughly 0.15 dB loss, sometimes more if poorly torqued. For a portable device, even two extra pairs—say, between the module, extension, and antenna—can eat 1 dB total.

Always measure return loss (S11) after final assembly. The antenna may look fine standalone, but metal frames or shielding cans can detune it by several decibels. If VSWR exceeds 2.0, adjust placement or add a small plastic spacer between antenna and housing.

Where should you mount the rubber duck to avoid metal detuning?

Ground clearance near rails/heat-sinks; avoid battery/shield cans

Try to give the antenna breathing room. About 10–15 mm of air gap from any metal surface usually keeps detuning manageable. In compact IoT gear, that’s not much space, but it’s enough to stop the near-field coupling that drags the frequency downward.

If you can’t avoid metal, add a nylon spacer or even a short plastic standoff. Anything non-conductive helps break the capacitive coupling path.

Batteries are another silent offender. They reflect energy unevenly, so one side of your signal looks stronger than the other. Before freezing your design, walk around with a simple RSSI meter or Wi-Fi app—you’ll see the “shadow” right away.

For embedded projects, you can compare this with TEJTE’s FPC antenna layout & tuning guide; the same spacing logic applies inside plastic housings.

Separation from other antennas to reduce CCI/ACI

If your product carries both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, or perhaps a cellular module, crowding the antennas is asking for cross-talk. Keep at least ¼ wavelength between them—roughly 30 mm at 2.4 GHz—and rotate their polarization if you can.

That spacing alone can recover 2–3 dB of throughput that no firmware tweak will ever fix.

When space is tight, do a quick two-port S-parameter test; aim for 15 dB isolation or better. It’s not a luxury—it’s the difference between clean coexistence and random packet loss.

Can an outdoor omni outperform a rubber-duck in semi-outdoor areas?

IP/UV needs, bracket torque, and when to move to mast-mount omnis

A rubber-duck antenna can survive humidity for months, but UV and temperature cycling will slowly kill it. The plastic dries, the seal cracks, and one rainy night later, water seeps through the SMA joint. If your node stays outside even part-time, look for IP65 or IP67 housings and UV-stable ABS or fiberglass shells.

At that point, it’s smarter to jump to a mast-mount omni. You’ll gain mechanical rigidity, cleaner grounding, and less coupling from nearby walls. Torque matters here—tighten around 0.6–0.8 N·m; more than that risks crushing the dielectric or shifting the resonance.

A fuller discussion of these trade-offs appears in TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna Guide, which compares bracket hardware and sealing methods side by side.

Weatherproof transitions: cold-shrink & self-amalgamating tape basics

If there’s one place moisture loves, it’s the connector joint. Seal it before it starts leaking. Most field techs use cold-shrink sleeves; some prefer self-amalgamating tape. Wrap from the antenna base downward, overlapping each layer so water can’t creep inward.

Also watch your materials—mixing brass SMA connectors with aluminum panels creates galvanic corrosion. The fix is simple: use nickel-plated bulkheads or an O-ring-sealed adapter. A five-cent gasket saves a five-hour repair call.

Can you validate placement fast before freezing the BOM?

RSSI/throughput snapshots; A/B angle tests; hand-detune checks

Grab a laptop, open a Wi-Fi scanner, and log RSSI readings every couple of meters. Rotate the antenna at a few angles—0°, 45°, 90°—and watch what happens. You’ll quickly see where the nulls sit.

Now do a hand-detune test: touch the antenna while watching the signal drop. If you lose more than 3 dB, it’s too close to where users grip the device. Add a thin plastic spacer or shift the connector a bit higher. These tiny moves often fix what no gain boost can.

Sometimes lower-gain antennas actually perform better indoors. A 3 dBi version tends to give smoother coverage than a 6 dBi that creates dead spots near ceilings.

Cable-first fault isolation: cable → connector → antenna swap order

When the prototype underperforms, start simple. Swap the pigtail first; micro-coax often fails from kinks or crimp fatigue. If that doesn’t help, change the adapter. Only last should you replace the antenna itself.

This “outside-in” approach saves time. Most of us have wasted hours chasing phantom VSWR only to find a bad crimp. Keep a small bench kit—two gains, both connector genders, one spare LMR patch—and you’ll solve 90% of field issues in minutes.

How should you order so your PO is manufacturable and fool-proof?

Gain/length, connector gender, color/angle, cable type/length, labels

| Spec Field | Typical Values | Purpose / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Gain & Length | 2 / 3 / 5 / 6 dBi; 5-20 cm | Match coverage area |

| Connector | SMA / RP-SMA (M/F) | Verify gender & thread type |

| Orientation | Straight / Right-Angle / Bendable | Fit device layout |

| Color | Black / White | Quick ID for dual SKUs |

| Cable Type | 0.81 / 1.13 / LMR-240 / LMR-400 | Balance loss vs flexibility |

| Cable Length | ≤ 0.15 m internal; up to 1 m external | Keep short to save margin |

| Label | "SMA-M RA 5 dBi" etc. | Prevent mix-ups |

Compliance (RoHS/REACH), torque, lead time/MOQ, packaging & RMA marks

| Item | Typical Range | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Compliance | Required for EU export | RoHS / REACH cert |

| Torque Spec | Prevents connector damage | 0.6 – 0.8 N·m |

| Lead Time | Plan for customs buffer | 2 – 3 weeks |

| MOQ | Lower for prototypes | 50 – 200 pcs |

| Packaging | Keeps VSWR stable post-ship | Individual PE bag + label |

| RMA Marks | Simplifies traceability | SKU + batch ID + inspector code |

What changed in 2024–2025 for indoor omni choices?

Tri-band APs in offices; 2.4 GHz stays alive for IoT reach and power

Office networks now juggle three bands at once: 2.4 GHz for low-power sensors, 5 GHz for main traffic, and 6 GHz for heavy data bursts.

The irony? The oldest band remains the most forgiving. At 2.4 GHz, walls and furniture aren’t deal-breakers. Devices sip less power, and the link budget tolerates noise better. That’s why engineers still spec rubber-duck Wi-Fi antennas into new IoT boards even while marketing brags about “Wi-Fi 7 ready.”

From late 2024 onward, more vendors began selling standardized rubber-duck antenna SKUs — same gain, same connector options, pre-tested for multi-band use. It shortens RF validation and keeps procurement clean across regions.

Standardized SKUs and replacement kits for field maintenance

Field techs used to carry bags of mismatched antennas. Now, many distributors offer universal maintenance kits: four pieces that cover every common combination — SMA male/female, RP-SMA male/female — each labeled and color-coded.

That tiny change saves hours of frustration. A blue boot instantly tells you it’s RP-SMA; red means SMA. No need to unscrew anything to check.

For factories and integrators, the benefit is consistency. One PO code can fit multiple devices, and maintenance teams don’t need to cross-reference spreadsheets or open housings just to confirm connector gender.

Practical Tools for Engineers and Buyers

A. Rubber-Duck Wi-Fi Link-Budget Mini-Calculator

If that final number dips below 6 dB, it’s time to shorten the pigtail, upgrade to LMR-240, or move the antenna away from metal.

Remember, at 6 GHz every cable behaves roughly twice as lossy as it does at 2.4 GHz — so always check the worst-band case.

| Parameter | Formula / Example | Typical 2.4 GHz Case |

|---|---|---|

| TX Power | tx_power_dBm | 18 dBm |

| Antenna Gain | antenna_gain_dBi | 5 dBi |

| Cable Loss | loss_per_m × length | 0.6 × 0.15 = 0.09 dB |

| Connector Loss | 0.15 × pairs | 0.3 dB (2 pairs) |

| EIRP | TX - Loss + Gain | 22.6 dBm |

| Path Loss | path_loss_dB | 78 dB |

| RX Sensitivity | rx_sensitivity_dBm | -90 dBm |

| Link Margin | EIRP - Path - RX | 34.6 dB |

B. Rubber-Duck Ordering & Compatibility Matrix

| Gain / Length | Connector | Angle | Color | Cable Type / Length | Mount | Labeling Example | Compliance | Torque (N·m) | Lead Time | MOQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 dBi / 5 cm | SMA-M | Straight | Black | 0.81 mm / 0.1 m | Device | "SMA-M 2 dBi" | RoHS | 0.6 | 2 week | 100 pcs |

| 3 dBi / 11 cm | RP-SMA-M | Right-angle | Black | 1.13 mm / 0.15 m | Bulkhead | "RP-SMA-M RA 3 dBi" | RoHS + REACH | 0.7 | 3 week | 200 pcs |

| 5 dBi / 16 cm | SMA-F | Straight | White | LMR-240 / 0.5 m | Panel | "SMA-F 5 dBi" | RoHS | 0.8 | 2 week | 50 pcs |

| 6 dBi / 20 cm | RP-SMA-F | Bendable | Black | LMR-400 / 1 m | External | "RP-SMA-F 6 dBi Flex" | RoHS | 0.8 | 3 week | 100 pcs |

When every PO includes these details, there’s no confusion between batches, factories, or distributors.

Procurement teams often tell us these templates save entire email threads — no one needs to guess connector orientation or torque specs.

FAQ — Rubber Duck Antenna

Does a 6 dBi rubber-duck really improve indoor coverage?

Yes, but not everywhere. The beam flattens out, giving you longer horizontal reach while thinning the vertical lobes. In multi-floor buildings, that can leave “quiet spots” directly above or below. For even coverage, 3–5 dBi is usually safer.

How do I tell RP-SMA from SMA on a live device without tools?

Look for the center contact: a pin means SMA male, a hole means RP-SMA male. The reverse is true for female jacks. Don’t force them — a mismatched pair will never seat cleanly.

How long can I run 0.81 mm or 1.13 mm coax before it hurts performance?

Keep it under six inches (≈ 0.15 m). Past that, every centimeter chews away fractionally more signal than you think — nearly a full dB per extra foot.

Where should I put the antenna on a handheld unit?

Avoid the user’s grip zone. Even a sweaty palm detunes the antenna by shifting its impedance. Two centimeters of plastic standoff can restore several dB of return loss.

When should I ditch a rubber-duck for an outdoor omni?

If sunlight, condensation, or rain are routine. Anything beyond IP54 exposure calls for an IP67 weatherproof omni with sealed boots and a mast bracket.

What quick checks prove the position is solid before you freeze the BOM?

Run a few RSSI sweeps while rotating the unit 90 degrees, test with and without hand contact, and ensure VSWR stays under 2:1. Consistency matters more than absolute numbers.

How can I prevent SMA / RP-SMA confusion in the field?

Color-code heat-shrinks: red = SMA, blue = RP-SMA. Keep the same color logic across every batch, and print it in your internal maintenance sheets — a tiny system that stops expensive returns.

How can I check if my rubber duck antenna is well matched?

Measure the VSWR using a handheld analyzer. Anything under 2:1 is fine for field gear, and under 1.5:1 is excellent. A mismatched antenna wastes power and can overheat your RF chain.

Final Thoughts

In RF design, “simple” hardware is rarely simple. A rubber duck antenna may cost a few dollars, but it can make or break link quality once gain, connector, and cable interact with the enclosure.

If you take one rule from this guide, let it be this: check the mechanical fit before chasing dBs. It’s easier to re-crimp a cable than to redesign a housing.

When you’re ready to explore companion topics, these in-depth references round out the picture:

- Omni coverage optimization — fine-tune indoor coverage.

- IP67 outdoor omni guide — protect links in harsh zones.

- Mast-mount torque reference — bracket and sealing practice.

- Internal FPC alternative — space-saving internal options.

- Metal clearance rules — avoid detuning inside enclosures.

Together, these articles form TEJTE’s ongoing Wi-Fi Antenna series — designed for engineers who prefer numbers over hype and hardware that works the first time.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.