WiFi Antenna Extension Cable: Loss, Length & End Types

Jan 7,2025

Preface

This is typically a schematic or photo of a flexible coaxial cable with standard SMA connectors, placed next to the “Preface” section. It aims to visualize the core object of discussion in this article—the antenna extension cable—and implies that this seemingly simple, inexpensive, often added-late passive component is precisely a common cause of “silent” performance degradation (e.g., in throughput, stability) in Wi-Fi links at 5GHz and 6GHz bands, setting the stage for the specific problem analysis that follows.

A wifi antenna extension cable rarely looks like a design risk. It’s passive, inexpensive, and usually added late—often after the router, access point, enclosure, and antenna choice already feel “done.”

That timing is exactly why it causes problems.

In real deployments, especially at 5 GHz and 6 GHz, antenna extensions quietly decide whether a Wi-Fi link feels solid or fragile. Range shrinks first. Then higher data rates stop holding. Nothing looks broken. Everything still screws together. Yet throughput drops, roaming becomes erratic, and installers start chasing firmware or antenna “gain” that isn’t actually the root cause.

Most of these issues don’t come from RF theory mistakes. They come from small assumptions:

“The connector fits, so it must be right.”

“It’s only a short cable.”

“Adapters don’t really matter.”

This guide is written from the field side of Wi-Fi design. It focuses on what actually fails in production, how to identify SMA vs RP-SMA ports correctly, when an extension cable is truly necessary, how far you can extend before loss becomes visible, and how to pair end-types so installations don’t come back for rework.

If you want a broader view of coax loss behavior across cable families, see the internal hub guide on coaxial loss and cable structure overview before diving deeper here.

Verify the port first: is your device SMA or RP-SMA?

Before discussing length, routing, or cable type, one check matters more than all others combined: is the port SMA or RP-SMA?

Misidentifying this single detail is still the most common cause of underperforming Wi-Fi links that otherwise look “correct.” The reason is simple—SMA connector and RP-SMA connector interfaces share the same outer thread size. Mechanically, they feel compatible. Electrically, they are not.

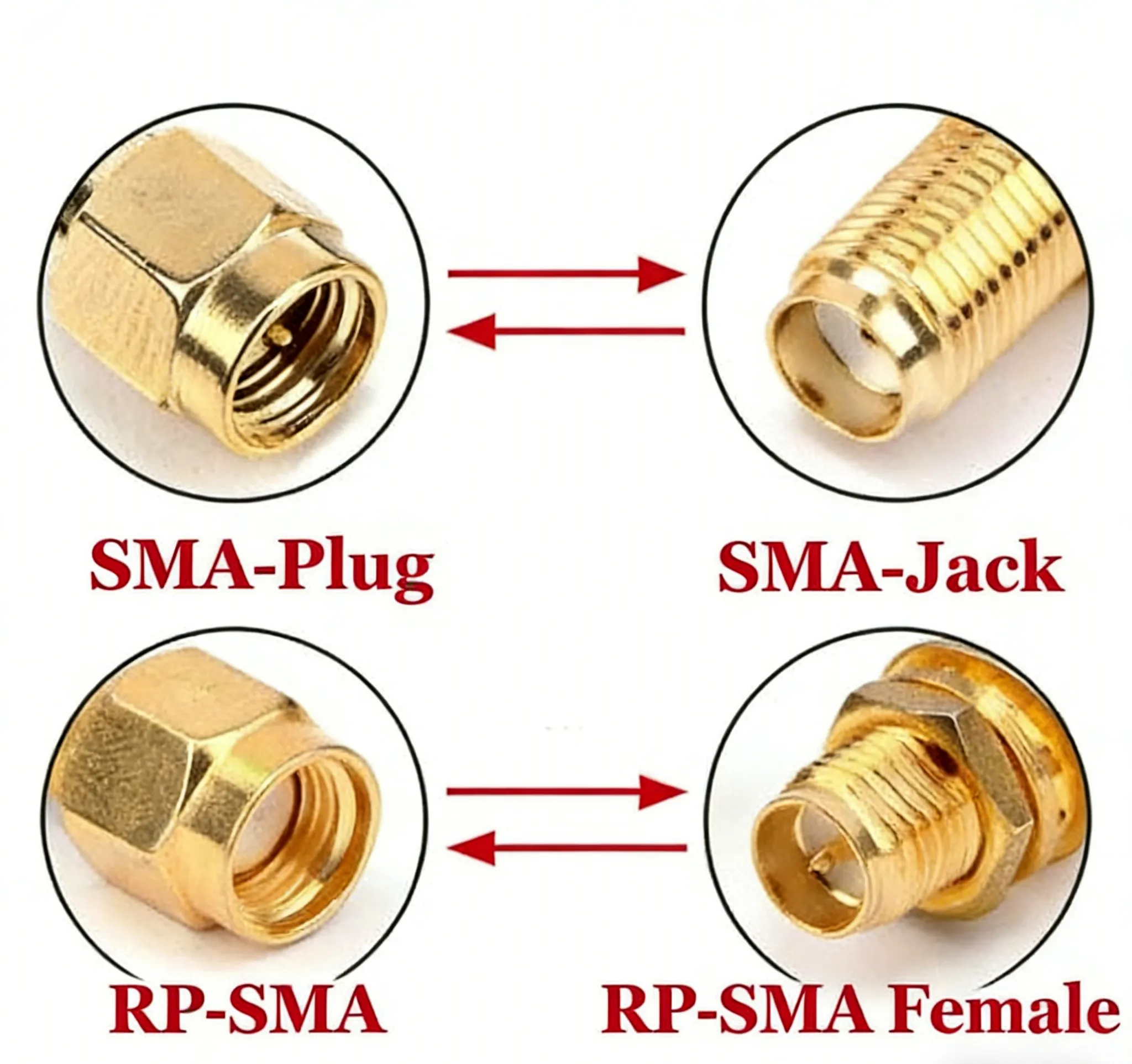

Thread × pin/hole quick ID (device vs antenna)

This image is presented in a 2x2 matrix table format, possibly supplemented with simplified connector outline drawings. It systematically shows the four connector types formed by the combination of two key features: “External/Internal Threads” and “Center Pin/Socket.” This diagram is a visual summary of the “four-quadrant check” and the subsequent quick identification table in the text. Its core purpose is to teach engineers to rely on objective physical characteristics rather than product photos or part labels for accurate and fast identification of SMA vs. RP-SMA interfaces, thereby preventing the most common ordering and pairing mistakes at the source.

| External thread | Center contact | Interface |

|---|---|---|

| Male thread | Pin | SMA Male |

| Male thread | Hole | RP-SMA Male |

| Female thread | Hole | SMA Female |

| Female thread | Pin | RP-SMA Female |

Two practical habits reduce mistakes:

- Use a flashlight. Center pins on worn ports are easy to miss.

- Identify both ends before ordering. A correct antenna connected through a mismatched extension still fails electrically.

This quick check eliminates most rp-sma vs sma errors before they happen.

Why “screws on but underperforms” happens

Building upon correct connector identification, this figure provides practical matching guidelines. It clarifies conventions in different markets (consumer vs. industrial), helping engineers establish the correct “expected pairing” model when ordering or assembling.

A mismatched SMA to RP-SMA connection will usually tighten without resistance. From the outside, everything feels normal. Inside the connector, the center conductors fail to mate properly.

What follows is predictable:

- Inconsistent or missing center contact

- Elevated return loss and poor impedance continuity

- Increased sensitivity to vibration and temperature

- At 5/6 GHz, immediate throughput degradation

This is why users often report that a wifi antenna cable “works but feels weaker than before.” The radio is fine. The antenna is fine. The connector interface is not.

For a deeper breakdown of identification errors and ordering pitfalls, you can cross-reference RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching & Ordering, which focuses specifically on connector-level mistakes.

Decide the strategy: when do you really need a wifi antenna extension cable?

A wifi antenna extension cable is not inherently bad. It’s just frequently used without a clear reason. In well-performing systems, extensions are added because the mechanical layout demands it, not because they feel convenient.

The fastest way to decide is to ask one question:

Does the antenna need to move across a physical boundary that the radio cannot?

If the answer is yes, an extension is justified. If the answer is “it would just be cleaner,” pause and reconsider.

Wall, rack, and outdoor runs — and the “minimum adapters” rule

This schematic, likely in a panel or composite format, depicts several common scenarios where antenna extension cables play a key role: e.g., a router installed inside a metal cabinet requiring an extension cable to bring the antenna outside for signal; an antenna needing to penetrate a wall or structural beam for line-of-sight; or an antenna separated from the main unit in an outdoor deployment. This image visually answers the question “When do you really need an antenna extension cable?” emphasizing that extensions exist due to mechanical layout demands, not merely for convenience. At the same time, it implies that in these scenarios, the design focus should be on minimizing the number of interfaces, not on shortening the cable at all costs.

Extensions are usually unavoidable when:

- A router or AP is mounted inside a metal rack or cabinet

- The antenna must clear shielding, doors, or structural beams

- Outdoor placement is required for line-of-sight or coverage shaping

- Regulatory or safety rules require separation from users or electronics

In these cases, the design goal is not “shortest cable at all costs.” It’s fewest interfaces. Each additional adapter or connector pair adds loss, mismatch risk, and long-term reliability exposure.

A clean extension path typically looks like this:

Device port → single extension cable → antenna

What causes trouble is the slow creep of adapters after the fact:

Device → adapter → extension → adapter → antenna

Even if each connection looks acceptable on its own, the chain is not.

When switching to an internal sma antenna cable is the better option

If the antenna relocation is entirely inside the enclosure, an internal sma antenna cable often outperforms an external extension.

This applies when:

- The antenna only needs to move a few centimeters

- The enclosure already provides RF-transparent windows

- Mechanical clearance, not distance, is the constraint

Replacing a short extension plus adapters with a single internal jumper usually results in:

- Lower insertion loss

- Better return loss

- Less connector stress during assembly

Many “marginal” Wi-Fi links stabilize immediately after this change—without touching firmware, antennas, or power settings.

How far can you extend at 5/6 GHz before throughput tanks?

Connector and adapter stacking penalties

| Common cable type | Loss per ft @ 900 MHz | Loss per ft @ 2.4 GHz | Loss per ft @ 3.4 GHz | Loss per ft @ 5.1-5.8 GHz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LMR-100 | 0.23 dB/ft | 0.39 dB/ft | 0.47 dB/ft | 0.643 dB/ft |

| LMR-400 | 0.228 dB/ft | 0.391 dB/ft | 0.532 dB/ft | 0.641 dB/ft |

| RG-174 | 0.314 dB/ft | 0.602 dB/ft | 0.769 dB/ft | 1.113 dB/ft |

| RG-178 | 0.55 dB/ft | 0.89 dB/ft | 1.02 dB/ft | 1.38 dB/ft |

| RG-58 | 0.137 dB/ft | 0.258 dB/ft | 0.328 dB/ft | 0.479 dB/ft |

Cable loss is only part of the story. Every mated interface contributes its own penalty.

A conservative, deployment-safe rule used by many RF teams:

- ≈ 0.2 dB per connector or adapter interface

That number includes contact loss, mismatch, and real-world assembly variance. It’s not worst-case—but it’s realistic.

Stack three or four interfaces, and you’ve already burned nearly a decibel before counting cable loss.

Length–Loss Quick Estimator

Inputs

- Frequency band: 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz

- Cable type (example: RG178)

- Cable length L (meters)

- Number of intermediate connectors/adapters n

Estimator

Total Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

Typical attenuation values for RG178

| Frequency band | α (dB/m) |

|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | ~ 1.0 |

| 5 GHz | ~ 1.8 |

| 6 GHz | ~ 2.2 |

What the loss actually means for throughput

| Total added loss | Observed impact | Recommended action |

|---|---|---|

| < 1 dB | Minor, often invisible | Leave as-is |

| 1–2 dB | Noticeable at higher MCS | Shorten cable or reduce adapters |

| > 2 dB | Clearly degraded | Change cable type or layout |

For most wifi antenna extension cable deployments at 6 GHz using RG178, the following holds true in practice:

- 0.1–0.3 m: Very safe

- 0.5 m: Usually acceptable with clean connectors

- 1 m: Sensitive; works only if interfaces are minimal

- >1 m: Expect visible throughput loss

This is why sma extension cable length tiers matter more at higher bands than at 2.4 GHz, even when everything “meets spec.”

For a deeper background on how coax structure affects attenuation across RG families, the internal reference coaxial loss and cable structure overview provides useful context.

Pair it right the first time: what end-types avoid returns?

Router and access point defaults

This is likely a close-up schematic showing the back or top of a typical home wireless router, highlighting its antenna interface(s). The image would clearly label the device port as RP-SMA Female and the matching external antenna as RP-SMA Male. This diagram is used to illustrate the dominant connector convention in consumer Wi-Fi equipment, explaining that this design (reversed center contact) is often intended to reduce the likelihood of users connecting uncertified high-gain antennas. Understanding this convention helps engineers avoid mistakenly applying it to industrial or IoT devices that use the SMA standard.

Most consumer Wi-Fi routers and access points ship with:

- Device port: RP-SMA Female

- Antenna: RP-SMA Male

This convention reduces the chance of users connecting non-certified antennas, which is why rp-sma antenna interfaces dominate consumer gear.

Industrial and IoT defaults

Industrial radios, gateways, and embedded modules more often use:

- Device port: SMA Female

- Antenna: SMA Male

The choice is deliberate. SMA reduces accidental cross-compatibility with consumer antennas and gives designers tighter control over system configuration.

Adapters vs compliance (EIRP trade-offs)

Adapters do more than add loss. They also affect effective isotropic radiated power (EIRP).

- Added loss reduces radiated output

- That can help with compliance

- But it also reduces coverage margin

If compliance is part of your design constraints, treat adapters as a designed element, not an afterthought. Relying on random adapter stacks to “fix” power issues usually creates inconsistent field results.

For a focused discussion on connector pairing errors and ordering checks, see RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching & Ordering.

Plan the panel feed-through: how to spec an SMA bulkhead correctly?

Once the antenna leaves the enclosure, the panel interface becomes a mechanical, electrical, and environmental boundary. This is where sma bulkhead selection matters far more than most designs anticipate.

A bulkhead that is “almost right” often works on day one—and then degrades quietly under vibration, thermal cycling, or repeated handling.

Hole size and stack-up math that actually works

This is a cross-sectional schematic showing the detailed stack-up of an SMA bulkhead connector installed through a panel. The image clearly labels the thickness or height of each component: panel thickness, flat washer (if used), compressed O-ring thickness, nut engagement length, and safety margin. This diagram visualizes the “practical stack-up calculation” formula described in the text, emphasizing that specifying a bulkhead by thread size alone is insufficient. The entire mechanical stack must allow for proper torque application, effective sealing, and contact stability; otherwise, it can lead to installation stress, seal failure, or performance degradation under long-term vibration.

Specifying a bulkhead by thread size alone is not enough. What matters is whether the entire stack-up allows proper torque, sealing, and contact stability.

A practical stack-up calculation looks like this:

Total required thread length =

- Panel thickness

- flat washer (if used)

- O-ring (compressed, not free height)

- nut engagement length

- safety margin (≈1–2 thread pitches)

If the thread is too short, installers compensate with torque. That stresses the dielectric and deforms the connector interface.

If the thread is too long, sealing suffers and the connector may rock under vibration.

This is why panel failures often show up months later as intermittent RSSI drops rather than obvious mechanical damage.

For a deeper, dimension-focused breakdown, see SMA Bulkhead: Panel Hole Size, Thread Length & Sealing.

Single-nut versus flange styles: when anti-rotation matters

Bulkhead styles solve different problems:

- Single-nut bulkhead

- Faster assembly

- Smaller footprint

- Suitable for fixed indoor equipment

- 2-hole / 4-hole flange bulkhead

- Prevents connector rotation

- Better vibration resistance

- Preferred for vehicles, machinery, and outdoor enclosures

In real deployments, rotation damage often starts electrically, not mechanically. The connector looks tight, but the internal contact alignment has already shifted.

Route inside the chassis without stressing the coax

Bend radius, strain relief, and sharp-edge avoidance

A simple rule that holds across most small coax types:

- Minimum bend radius ≥ 10× cable outer diameter

Beyond that:

- Add strain relief near connectors

- Keep distance from sharp sheet-metal edges

- Avoid routing that flexes during lid removal

These steps don’t improve performance on day one. They prevent degradation six months later.

Why one sma male to female cable beats two back-to-back adapters

This is a schematic or photo of a short jumper cable with an SMA male connector on one end and an SMA female connector on the other. It might be compared side-by-side with the complex solution of two back-to-back adapters plus a short jumper. This image aims to support a key recommendation in the text: when internal device connections or direction changes are needed, using a single SMA male-to-female jumper cable is far superior to using two back-to-back adapters. This approach reduces the number of mated interfaces, improves return loss consistency, handles vibration better, and simplifies assembly and inspection. It is an effective method for solving many “random” Wi-Fi performance issues at higher frequency bands.

Two adapters plus a short jumper look modular. Electrically and mechanically, they are inferior.

A single sma male to female cable:

- Reduces mated interfaces

- Improves return loss consistency

- Handles vibration better

- Simplifies assembly and inspection

In troubleshooting, replacing back-to-back adapters with one jumper resolves a surprising number of “random” Wi-Fi complaints—especially at 5 GHz and above.

This is one of those fixes engineers usually learn only after field returns.

What belongs on the PO so warehousing won’t bounce it?

Extension cable PO checklist

Presented in a tabular format, this image is a visualization of the “Extension cable PO checklist” from the text. The table lists the key fields that must be explicitly specified, such as: Connector family (SMA/RP-SMA), Center contact (Pin/Hole), End configuration (M–F/M–M), Cable type (e.g., RG178), Exact length, Bulkhead/flange requirement, Waterproof cap, etc. This diagram emphasizes that ambiguous purchase orders are a primary cause of delays and incorrect shipments. Using such a checklist forces alignment between engineering, procurement, and warehousing, eliminating guesswork downstream and significantly reducing fulfillment delays and rework.

| Field | Example |

|---|---|

| Connector family | SMA / RP-SMA |

| Center contact | Pin / Hole |

| End configuration | M-F / M-M |

| Cable type | RG178 |

| Length | 0.3 m |

| Bulkhead or flange | Yes / No (2-hole / 4-hole) |

| Waterproof cap | Yes / No |

| Quantity | 20 |

Copy-ready PO note

RP-SMA Male to RP-SMA Female, RG178, 0.3 m, no intermediate adapters, non-bulkhead, no waterproof cap.

Clear notes like this eliminate most fulfillment delays and rework.

Practical FAQs

How can I confirm RP-SMA vs SMA on a router without opening the case?

Use the thread and center-contact check with a flashlight. No disassembly is required.

At 6 GHz, which RG178 lengths are still safe?

0.3 m is very safe. 0.5 m is usually acceptable. 1 m works only with minimal connectors.

Is a single M-to-F jumper better than two back-to-back adapters?

Yes. Fewer interfaces mean lower loss and better long-term stability.

What O-ring compression should I target for an SMA bulkhead?

Enough to seal without forcing torque. Over-compression usually causes more harm than under-compression.

Can I use an RP-SMA antenna on an SMA jack and still meet EIRP limits?

Only with a proper adapter—and the added loss must be accounted for explicitly.

What bend radius is acceptable for RG178 around standoffs?

At least 10× OD. More space improves longevity.

Which PO fields prevent warehouse rejection?

Connector family, pin/hole, end configuration, cable type, and length—always.

Closing perspective

A wifi antenna extension cable is never just “extra wire.”

At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, it becomes part of the RF system whether you intend it or not.

Correct port identification, disciplined length control, minimal adapters, proper bulkhead selection, and clean internal routing are what separate stable deployments from fragile ones. None of these steps are complicated—but skipping any one of them shows up later as lost throughput, inconsistent range, or unexplained returns.

If you want to sanity-check connector pairing and ordering logic across projects, the companion guide RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching & Ordering remains a useful cross-reference.

Design it once. Install it cleanly. And the Wi-Fi link will behave the way the datasheet promised.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.