WiFi Antenna Extension Cable: Length Loss & Connector Matching

Jan 1,2025

Serving as the opening illustration of the article, this figure uses a specific, common hardware setup to visually introduce the core topic: the seemingly simple antenna extension cable is actually a key variable determining the field stability of Wi-Fi systems, especially at 5GHz/6GHz.

A wifi antenna extension cable almost never looks like the source of a weak wireless link. It’s passive, inexpensive, and usually added late in a project—often after the enclosure, antenna choice, and even regulatory planning already feel “finished.” In real Wi-Fi systems, especially at 5 GHz and 6 GHz, that last-minute extension often decides whether a link feels stable or quietly fragile. Nothing fails outright. Instead, higher MCS rates drop first, roaming becomes inconsistent, and coverage shrinks just enough to frustrate users without pointing clearly to the cause.

Field experience shows that most of these issues trace back to three small assumptions: misidentifying SMA vs RP-SMA, adding adapters for convenience, or choosing extension length without accounting for high-frequency coax loss. This guide focuses on how engineers avoid those traps in practice. It doesn’t rehash RF theory—you already know that—but walks through identification, matching, and length decisions the way they actually play out on routers, access points, and industrial gateways.

Is my jack SMA or RP-SMA—how do I tell in 10 seconds?

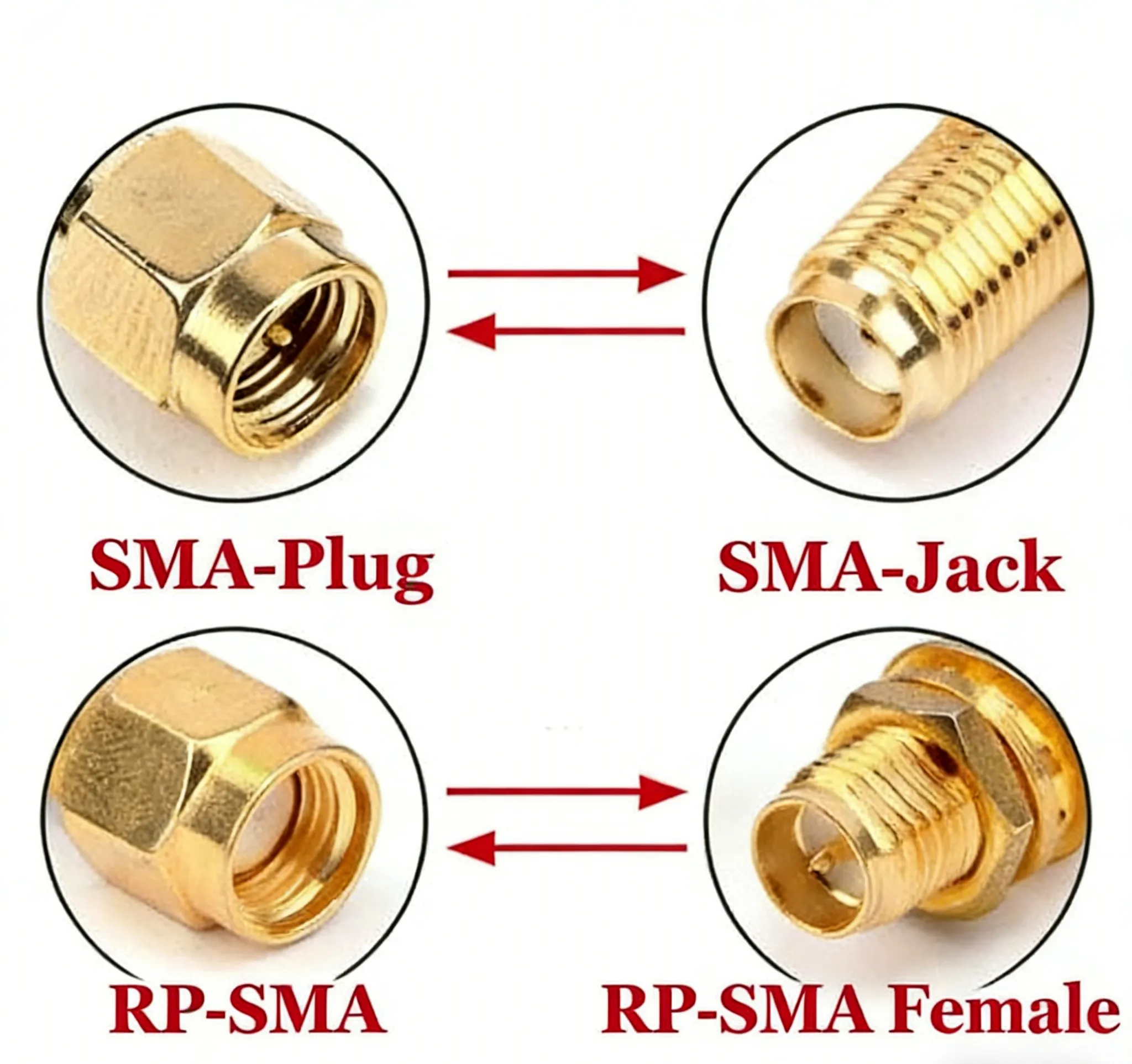

This figure is a key visual reference for connector identification. Through side-by-side comparison, it intuitively reveals the most fundamental physical difference between RP-SMA and SMA connectors: one has a center socket, the other a center pin. Combined with the textual check steps below, it provides a practical method for identification within 10 seconds.

Confusion between SMA and RP-SMA connectors remains one of the most common causes of wasted time and unnecessary returns in Wi-Fi projects. The mistake usually comes from trusting thread appearance alone. Threads are only half the story.

To identify the connector correctly, ignore labels and look at two physical features only: the outer thread and the center contact. External threads indicate a “male body,” internal threads a “female body.” Separately, a solid center pin means a male signal contact, while a hollow socket indicates a female signal contact. Combining those two observations gives a complete and unambiguous result.

An external thread with a pin is SMA male. An internal thread with a hole is SMA female. An external thread with a hole is RP-SMA male. An internal thread with a pin is RP-SMA female. Every SMA-family connector fits one of these four cases, with no overlap.

This is also why SMA and RP-SMA cause so much confusion: their shells are intentionally similar, while the center contact is reversed. Two connectors can screw together smoothly and still fail electrically. If both mating sides have pins—or both have sockets—the RF path is broken even though the threads engage. For background on how this standard evolved, the overview on the SMA connector explains the historical rationale, but in daily work the “thread × pin” check is faster and more reliable.

How do I match both ends without mistakes—what are the typical pairs?

Building upon correct connector identification, this figure provides practical matching guidelines. It clarifies conventions in different markets (consumer vs. industrial), helping engineers establish the correct “expected pairing” model when ordering or assembling.

Once the connector type is identified correctly, most Wi-Fi systems follow predictable pairing conventions. Knowing those conventions helps catch errors before cables are ordered.

Consumer routers and access points almost always use RP-SMA on the device side. The typical pairing is an RP-SMA female jack on the router with an RP-SMA male antenna. This convention is widespread across consumer Wi-Fi gear and explains why most off-the-shelf Wi-Fi antennas default to RP-SMA-M. If you want a deeper discussion of why consumer gear adopted this pattern and how to spot exceptions, the article RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Match & Ordering Guide covers those edge cases in detail.

Industrial and IoT equipment usually does the opposite. Gateways, embedded radios, and test instruments commonly expose an SMA female jack, paired with an SMA male antenna. Standard SMA is favored in these environments because documentation is clearer, adapters are easier to source, and mixed RF systems are easier to audit. This choice also simplifies panel mounting and sealed enclosures, which becomes important once antennas leave the PCB and pass through metal housings.

How long can I extend before 5 / 6 GHz range drops?

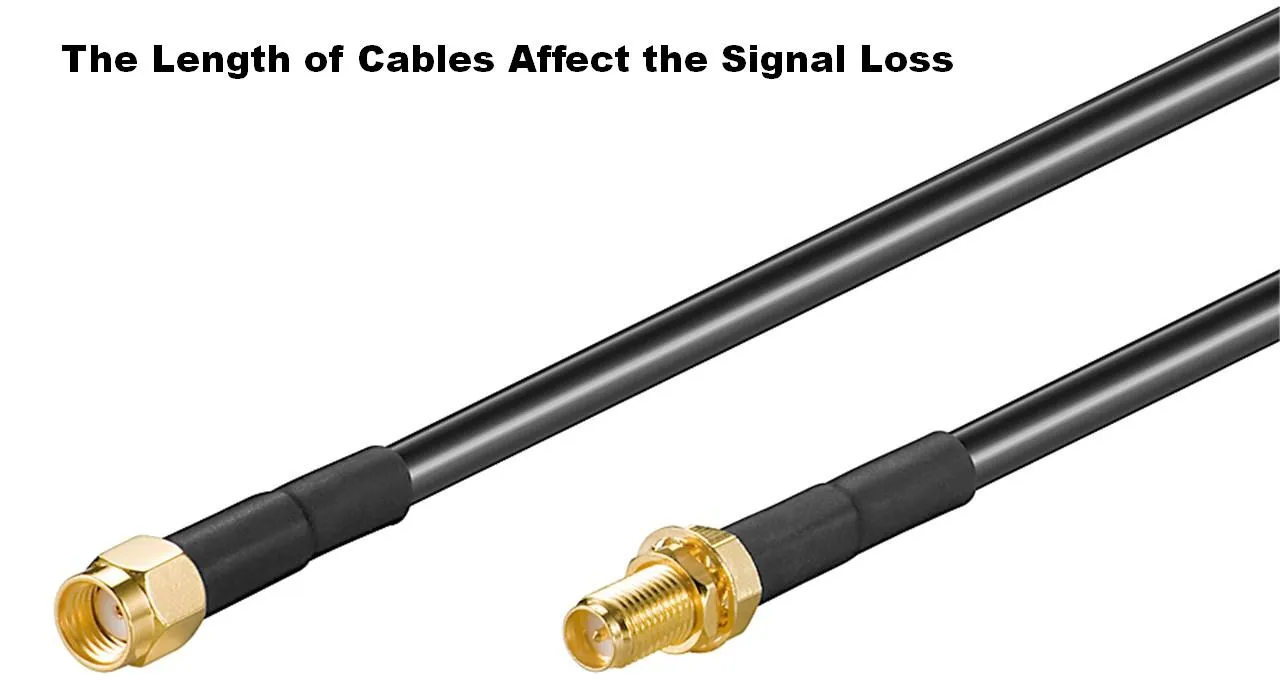

This figure is one of the core technical illustrations in the document, located in the “The Length of Cables Affect the Signal Loss” section. It transforms the theory of sharply increasing coaxial cable attenuation at high frequencies (5/6 GHz) into an intuitive visual warning through data curves, directly supporting the subsequent “Quick Estimator” and engineering recommendations on maximum safe extension lengths, emphasizing the necessity of meticulous length budgeting in high-frequency applications.

After connector matching, extension length is the next silent failure point. At 2.4 GHz, short extensions are often forgiving. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, the same assumptions break down quickly. Coaxial attenuation rises sharply with frequency, and thin cables amplify that effect.

A wifi antenna extension cable makes sense when it solves a mechanical or layout problem—moving an antenna out of a metal enclosure, clearing shielding cans, or improving line-of-sight. It becomes risky when added simply because “it’s only a short cable.” Loss accumulates in two places: along the cable itself and at every connector interface.

In field practice, engineers often budget approximately 0.2 dB per connector as a conservative estimate. Adapters count as connectors, and some introduce even more loss and reflection. At 6 GHz, two extra interfaces can negate the gain difference between antenna models, leaving the system worse off than before.

Extension Loss Quick Estimator

This estimator is not a substitute for lab characterization, but it is accurate enough to prevent poor design choices.

Inputs: operating frequency (2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz), cable type (for example RG178), length L in meters, number of connectors n, and whether an adapter is used.

Estimator:

Total Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

Typical field attenuation values for RG178 are approximately 1.5 dB/m at 2.4 GHz, 2.5 dB/m at 5 GHz, and 3.0 dB/m at 6 GHz. For example, a 0.5 m extension at 6 GHz with three connectors yields roughly 3.0 × 0.5 + 0.2 × 3 ≈ 2.1 dB of total loss. That is enough to cause visible throughput loss on marginal links.

In practice, extensions of 0.1–0.3 m are usually safe, 0.5 m is acceptable with clean connectors, 1 m often shows noticeable degradation at 5 GHz and above, and anything longer should trigger a redesign or a lower-loss cable choice. Teams that ignore this math often try to recover later with higher-gain antennas, which introduces new problems with pattern distortion or regulatory limits on effective radiated power. For broader antenna behavior and gain concepts, the general overview on radio antennas provides useful context without going deep into theory.

Do I need a panel feed-through—how do I size an SMA bulkhead correctly?

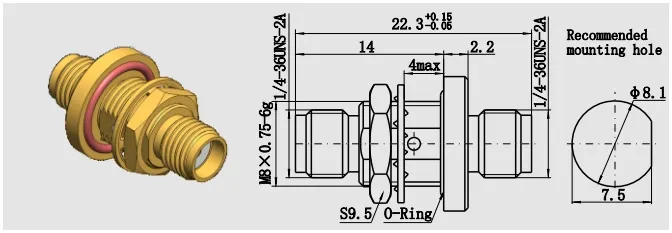

This figure concretizes the concept of a “bulkhead connector,” serving as a visual starting point for discussing “how to correctly select thread length.” It emphasizes that choosing a bulkhead connector is a mechanical engineering problem, not just an electrical connection one.

Once an antenna leaves the PCB and passes through a metal enclosure, the question is no longer electrical first—it’s mechanical. Many Wi-Fi range problems blamed on cables or antennas actually start with a poorly sized SMA bulkhead that loosens, leaks, or never fully seats.

A bulkhead connector is not “one length fits all.” The correct thread length depends on the full stack between the connector shoulder and the nut. That stack always includes the panel thickness, but it often includes more than engineers expect.

Stack height: panel, washer, gasket, and cap

To size a bulkhead correctly, measure the total stack height: the metal panel itself, any flat washer, any sealing gasket or O-ring, and any external waterproof cap or weather boot. Add these together and then add a small margin—typically 1 to 2 mm—to ensure full thread engagement. That margin matters. Too little thread and the nut barely grabs; too much thread and the connector may bottom out before the gasket compresses, defeating the seal.

This mistake shows up frequently on outdoor or semi-outdoor Wi-Fi equipment where a gasket is added late “just in case.” The electrical performance remains fine, but vibration or temperature cycling slowly loosens the connector over time.

If you’re working through enclosure decisions in more depth, the practical checklist in SMA Bulkhead Panel Drilling & IP67 Sealing in Practice walks through hole sizing, torque, and sealing trade-offs that don’t appear on datasheets.

Single-nut bulkhead vs flange mount

Electrically, a single-nut bulkhead and a 2-hole or 4-hole flange mount behave the same. Mechanically, they do not. A single nut is fast and cost-effective, and it works well for indoor equipment with low vibration. Flange mounts add anti-rotation and more consistent gasket compression, which makes them preferable for outdoor enclosures, vehicle installations, or any system that will be handled repeatedly.

Choosing between them is rarely about RF specs; it’s about how confident you want to be that the connector will still be tight a year from now.

What should I use inside the chassis: SMA antenna cable or a male-to-female jumper?

This figure supports the discussion on internal chassis routing. It provides a simple, memorable engineering guideline (5-10 times the outer diameter) to help designers avoid hidden failures caused by mechanical stress when routing in tight spaces.

Inside an enclosure, the goal changes again. You’re no longer optimizing for weather sealing or mechanical robustness, but for short, predictable RF paths that don’t degrade over time.

In most cases, a short male-to-female SMA antenna cable is preferable to chaining adapters. Every adapter introduces another impedance transition and another mechanical joint that can loosen. A single continuous jumper minimizes both.

Bend radius and strain relief—small details, real failures

Coaxial cables fail quietly when bent too tightly. A practical rule used in field builds is a minimum bend radius of 10× the cable’s outer diameter. For thin cables like RG178, this is still larger than many designers expect, especially near connectors.

Failures often appear months later as intermittent RSSI drops caused by fatigued center conductors near the connector crimp. Simple strain relief—tying the cable down so the connector doesn’t carry mechanical load—prevents this entirely.

Routing near metal and noise sources

Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack—what’s the real cost?

This figure serves as a strong visual warning, summarizing the problem of “adapter abuse.” It indicates that while each adapter solves an immediate mechanical problem, using them in series significantly increases insertion loss, reflection points, and failure probability, especially in high-frequency applications.

Adapters are tempting because they solve immediate mechanical mismatches. From a purely physical standpoint, adapting an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack works. From an RF standpoint, it’s a compromise.

Every adapter adds insertion loss and increases the chance of reflection, especially as frequency climbs. At 5 GHz and above, even small discontinuities matter. One adapter might be tolerable; two in series often push a marginal link over the edge.

Physical compatibility vs RF performance vs compliance

Another cost is regulatory. In certified products, EIRP margins are often tight. Adding loss through adapters can tempt teams to compensate by selecting higher-gain antennas later. That change can affect radiation patterns and compliance in ways that are far harder to justify during audits.

The preferred order of fixes in practice is simple: match the connector correctly first, shorten the cable run second, reduce the number of interfaces third, and only use adapters as a last resort. This approach keeps both RF performance and compliance predictable.

For background on why antennas behave this way at a system level, the general explanation of radiation and gain in the radio antenna overview is useful context without diving into equations.

Field takeaway before ordering anything

By this point, a pattern should be clear. Problems with wifi antenna extension cable assemblies rarely come from exotic RF effects. They come from small mechanical and routing decisions that compound quietly: a bulkhead that’s slightly too short, an adapter added for convenience, a jumper bent tighter than it should be.

None of these mistakes stop a system from working on day one. They show up later, when throughput drops, returns start coming in, or support teams can’t reproduce customer complaints.

What belongs on my PO so I avoid returns and rework?

This figure shifts the discussion focus from technical details to supply chain practices. It represents the physical product that will ultimately be ordered and delivered, emphasizing the importance of providing extremely clear technical specifications in the purchase order (PO) to prevent returns and rework due to vague descriptions.

By the time a wifi antenna extension cable reaches purchasing, most technical decisions are already made—or at least assumed. That’s exactly why errors slip through. Returns almost never happen because a cable is electrically defective; they happen because something was left ambiguous.

A connector that “looked right.”

A length that sounded close enough.

An assumption that SMA and RP-SMA were interchangeable.

The safest way to prevent that cycle is to treat the purchase order itself as part of the RF design.

Extension Cable Ordering Checklist

Before releasing a PO, every one of the following fields should be explicitly confirmed:

- Connector family: SMA or RP-SMA

- Signal gender: pin or hole (not just “male/female”)

- Ends: M–F, M–M, or F–F

- Cable type: for example RG178

- Length: 0.1–2 m (exact value, not a range)

- Bulkhead or flange: yes or no

- Waterproof cap or gasket: yes or no

- Quantity

- Panel thickness and hole diameter: required if a bulkhead is used

None of these items are redundant. Omitting any one of them forces someone downstream to guess, and guessing is how mismatched cables get built.

Copy-ready PO note (engineer-tested)

WiFi antenna extension cable, RG178, length 0.3 m.

Device end: RP-SMA male (external thread, hole).

Antenna end: RP-SMA female (internal thread, pin).

No adapters. Indoor use only.

This level of clarity eliminates interpretation on the supplier side and makes inspection trivial on receipt. Teams that adopt this habit typically see return rates drop to near zero.

How do all these decisions tie together in practice?

This figure serves as a summative visualization of the article's technical content, elevating the core message. It emphasizes that excellent design requires systemic thinking, treating connector identification, path length, mechanical installation, and internal routing as a whole to be weighed, rather than optimizing individual aspects in isolation.

By now, it should be clear that extension cables are not isolated components. Connector type, length, bulkhead choice, and routing all interact. Changing one often forces trade-offs elsewhere.

For example, adding a panel feed-through might improve mechanical robustness but increase connector count. Extending length to clear an enclosure wall might require a lower-loss cable to stay within the link budget. Swapping SMA for RP-SMA late in a project can cascade into antenna and compliance changes.

Engineers who consistently get predictable Wi-Fi performance tend to follow a simple hierarchy. First, identify the connector correctly—no assumptions. Second, keep the RF path as short and direct as the enclosure allows. Third, minimize interfaces. Everything else is secondary.

If you want a broader view of how cable choice fits into overall RF loss planning, it’s worth revisiting the system-level perspective in TEJTE’s RG Cable Guide, which ties coax selection, frequency, and attenuation together beyond just Wi-Fi use cases.

Final field perspective

A wifi antenna extension cable doesn’t fail loudly. It fails quietly, by shaving a few dB where you can least afford them. At 2.4 GHz, those losses are often survivable. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, they’re not.

The good news is that none of the solutions are exotic. Correct connector identification, realistic length expectations, proper bulkhead sizing, clean internal routing, and unambiguous ordering language solve the vast majority of real-world issues. These are habits, not advanced RF tricks.

When those habits are in place, extension cables stop being a variable you worry about. They become what they should have been all along: boring, predictable, and invisible in the final system.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell RP-SMA from SMA on my router without opening the case?

How long can a 6 GHz extension be before throughput drops noticeably?

Is a male-to-female jumper better than chaining two adapters inside a chassis?

What thread length should I choose for an SMA bulkhead on a 1.5 mm aluminum panel with a gasket?

Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack and still pass compliance (EIRP)?

What bend radius is safe for RG178 inside tight enclosures?

Should I add a waterproof cap for semi-outdoor installs, or is indoor hardware good enough?

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.