SMA to N Cable Guide for Outdoor Antennas and RF Feedlines

Jan 12,2026

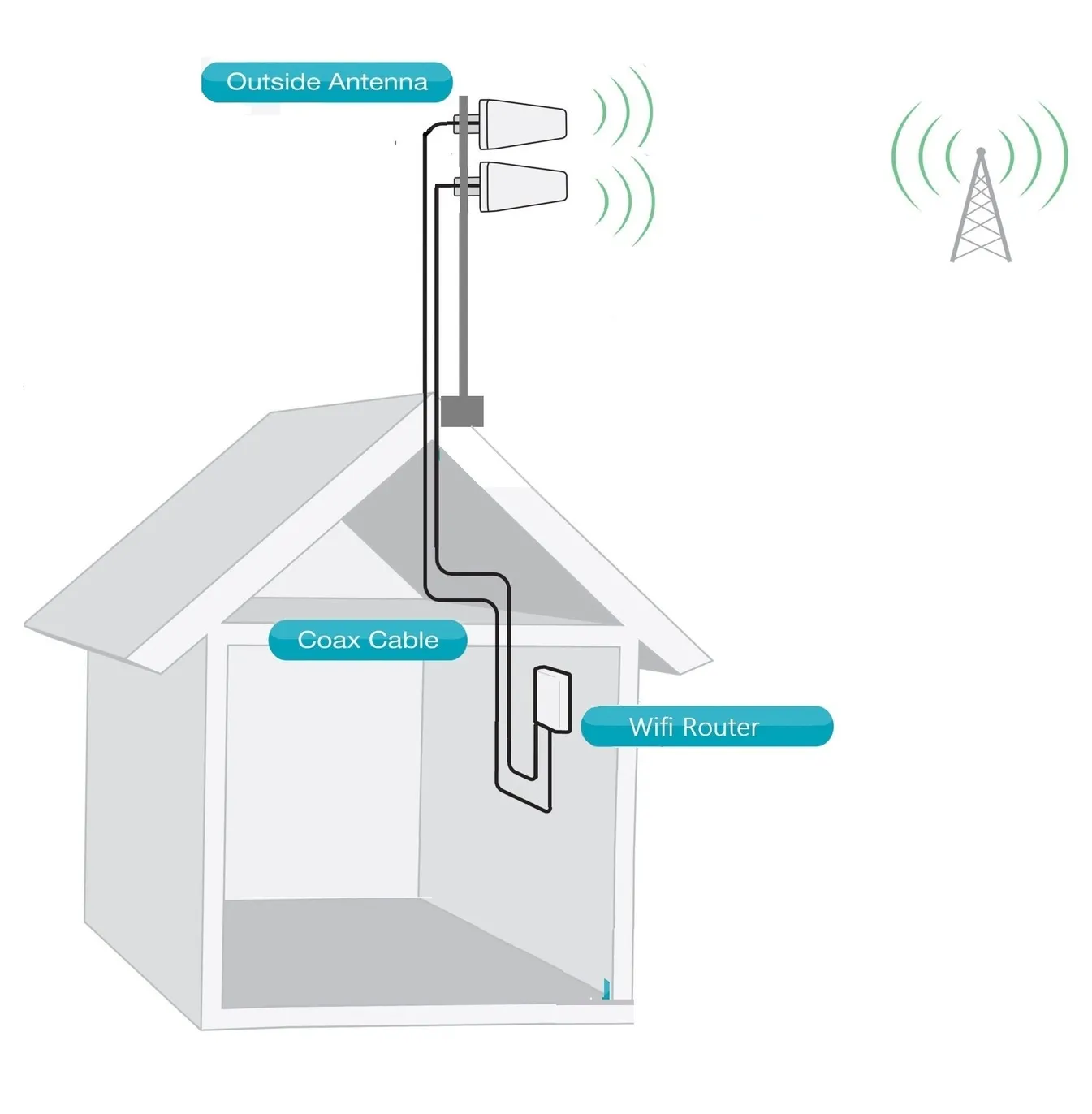

This introductory graphic establishes the core application scenario for SMA to N cables: bridging the gap between indoor RF devices (with SMA ports) and outdoor, robust antenna/feedline systems (with N-type ports). It highlights the cable as a critical transition component, not just a passive jumper.

Where does an SMA to N cable belong in real antenna and RF feedline layouts?

This diagram provides a concrete example of the cable's use case. It visually maps the signal path from an indoor device (router with SMA) through the cable to an outdoor N-type antenna, emphasizing the cable's role in crossing the environmental boundary.

In most RF projects, the SMA to N cable doesn’t show up on the first schematic. Engineers usually start with the radio, the antenna, and the enclosure. Only later—often when the hardware is already built—does the mismatch become obvious: the device speaks SMA, while the rooftop hardware expects N-type.

That moment matters more than it looks.

SMA and N connectors aren’t interchangeable choices made for convenience. They belong to different physical environments. SMA is compact, lightweight, and ideal for indoor electronics. N-type connectors, on the other hand, were designed for mechanical strength, outdoor exposure, and higher RF power. The sma to n cable exists precisely to bridge that divide without compromising either side of the system.

In real deployments—Wi-Fi access points, LTE/5G fixed wireless, SDR installations, or private RF links—the cable is not just a signal path. It becomes part of the mechanical structure. How and where you place the SMA–N transition determines whether the system survives weather, vibration, and time.

Mapping indoor SMA-based devices to outdoor N-type antennas and lightning arrestors

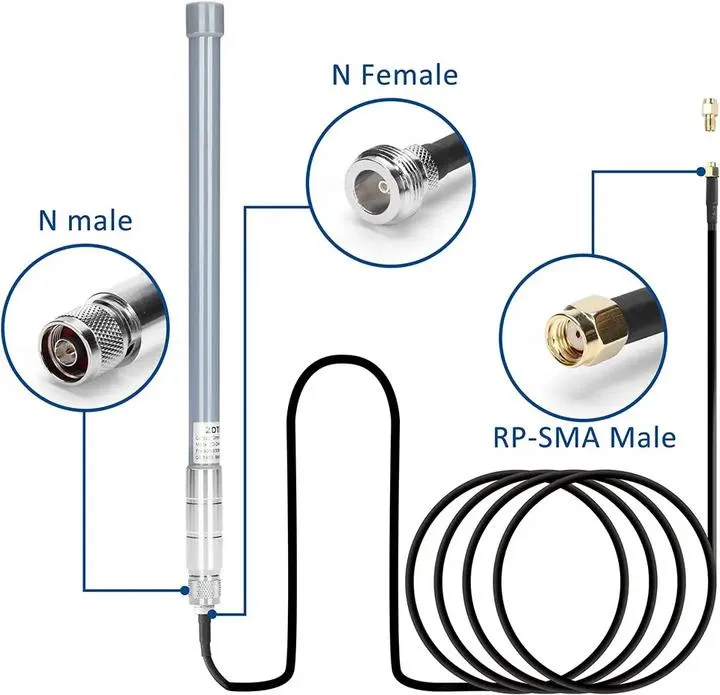

This product photo shows a common rigid adapter type. The guide uses it to illustrate the indoor side of the transition, often placed at the device or inside a cabinet before the feedline goes outside. It contrasts with the more robust cable assemblies recommended for outdoor transitions.

A typical deployment looks deceptively simple:

- Indoor router, CPE, radio module, or SDR with an SMA connector

- Wall or cabinet penetration

- Outdoor coaxial feedline

- Lightning arrestor

- Rooftop or mast-mounted antenna

What’s often overlooked is that this chain crosses two environments with very different constraints. Indoors, temperature is stable, moisture is controlled, and cables rarely move. Outdoors, connectors face UV exposure, rain, wind-induced vibration, and continuous mechanical load.

This is where the sma to n cable earns its place. By keeping the SMA end inside and transitioning to N-type before the cable enters the outdoor section, you allow each connector to operate in the environment it was designed for.

This same architecture shows up repeatedly in RF planning guides, including our broader discussions on coax routing and connector placement in the RG Cable Guide. The takeaway is consistent: outdoor robustness starts with connector choice, not just cable loss.

Separating lab-only sma to n adapter use from field-grade cable assemblies

This image visually distinguishes the two main hardware approaches. It underscores the guide's key message: a bare adapter is sufficient for controlled lab/rack environments, but a purpose-built cable assembly with outdoor-rated coax and proper strain relief is essential for reliable field deployments where mechanical stress and weather are factors.

In lab environments, a bare sma to n adapter is perfectly reasonable. Test benches, racks, and shielded rooms are controlled spaces. Cables are short. Loads are predictable. Adapters don’t see tensile stress or moisture ingress.

Problems start when that same logic is carried into the field.

An sma to n adapter is a rigid mechanical junction. When mounted outdoors or near a mast, it becomes a lever arm. Any movement in the cable transfers stress directly into the connector interface. Over time, that stress shows up as loosened threads, degraded return loss, or—in worse cases—physical damage to the SMA port on the device.

A properly built sma to n cable assembly, by contrast, distributes stress along the cable. The N connector handles outdoor exposure and mechanical load, while the SMA connector remains protected inside an enclosure or cabinet. This distinction is subtle on paper, but very obvious after a few seasons in the field.

Identifying when relying on an n to sma adapter at the mast is asking for trouble

This is likely a clear product shot of the recommended solution—a factory-assembled cable with an SMA connector on one end and an N-type connector on the other. It represents the integrated, reliable alternative to problematic adapter stacks at the mast or outdoor entry points.

One of the most common failure patterns in outdoor RF systems is the “adapter stack” at the mast:

N-type antenna → n to sma adapter → SMA jumper → indoor-grade coax

It works. Until it doesn’t.

Water intrusion is the usual culprit, but not the only one. Wind-induced motion creates micro-movements at the adapter interface. Temperature cycling slowly relaxes threaded connections. Each extra interface adds insertion loss and a new impedance discontinuity.

Experienced installers tend to follow a simple rule:

If it’s outdoors, keep it N-type.

That means using an SMA to N cable where the transition happens indoors, not at the mast. If you need to extend or reroute later, you still have a robust N-type interface to work with outside.

How should you choose between an SMA–N adapter and a full SMA to N cable run?

At first glance, adapters feel cheaper and simpler. One part instead of a custom cable. No lead time. No length decisions.

In practice, the choice is less about cost and more about system boundaries.

Using bare sma to n adapters only for short, rigid indoor transitions

There are situations where a bare adapter is the right tool:

- Connections entirely inside a rack or enclosure

- Short jumper lengths, typically under one meter

- No exposure to vibration, weather, or cable weight

For example, transitioning from an N-port instrument to an SMA jumper on a test bench is a textbook adapter use case. The adapter stays rigid, the cable is light, and nothing moves once connected.

In these scenarios, an adapter can actually reduce complexity. You avoid custom cable lengths and keep the system modular.

Preferring dedicated sma to n cable assemblies for outdoor-facing N connectors

Once the N connector is expected to see weather, strain, or continuous load, the balance shifts.

A dedicated sma to n cable allows you to:

- Place the SMA connector where it’s protected

- Use outdoor-rated coax (RG58, LMR-200, LMR-400)

- Control bend radius and strain relief from the start

This approach is standard in rooftop deployments and is echoed in many best-practice discussions around SMA cable routing, including our SMA Cable Selection Guide for RF and Antenna Systems. The pattern is consistent: adapters stay inside, cables handle transitions.

Avoiding stacked n to sma adapter chains when a single proper cable will do

Every additional adapter introduces three risks at once:

- Extra insertion loss

- Another impedance transition

- A mechanical failure point

Stacking adapters is rarely intentional. It usually happens incrementally—one quick fix at a time. But when you step back, a single sma to n cable of the correct length often replaces the entire chain.

From a system reliability standpoint, fewer interfaces almost always win.

What coax type and length actually make sense for SMA to N cables outdoors?

Thinking about length before loss becomes a surprise

This informational graphic provides practical, at-a-glance guidance. It likely illustrates how signal attenuation increases with length and frequency for common cable types, helping engineers make preliminary decisions about which coax is suitable for their planned run before detailed calculations.

Loss isn’t dramatic at first. A few meters here, a connector there—it all feels manageable. But RF systems fail by accumulation, not catastrophe.

As a rough planning reference:

- RG316 should stay within a few meters at higher frequencies

- RG58 is workable up to roughly 10–15 meters for Wi-Fi and LTE

- LMR-400 comfortably supports 30 meters or more, depending on band and budget

These aren’t limits. They’re warning signs. Once you approach them, it’s time to calculate instead of guessing.

What coax type and length actually make sense for your SMA to N cable outdoors?

This technical image focuses on a specific, high-performance coaxial cable type (LMR-400) often recommended for longer outdoor SMA to N runs. It likely shows key specs like inner/outer conductor materials, diameter, frequency rating, and typical loss values, providing concrete data for selection.

At planning time, exact loss numbers aren’t always necessary. What matters is knowing the order of magnitude and how it scales with length and frequency.

Typical attenuation ranges (rounded, real-world planning values):

| Coax Type | ~900 MHz | ~2.4 GHz |

|---|---|---|

| RG316 | High (~1.5-2.0 dB/m) | Very high |

| RG58 | ~0.6-0.7 dB/m | ~0.9-1.1 dB/m |

| LMR-400 | ~0.12-0.15 dB/m | ~0.20-0.23 dB/m |

These numbers align with manufacturer data and independent summaries commonly referenced in RF design discussions. Wikipedia’s overview of coaxial cable loss mechanisms—dielectric loss, conductor loss, and skin effect—explains why frequency matters so much, even when the cable length stays the same.

The takeaway is simple:

doubling frequency doesn’t just double loss—it often amplifies it enough to erase your link margin if the cable choice is marginal.

Translating loss numbers into practical length decisions

Engineers often ask, “How long is too long?” The honest answer is: it depends on what you can afford to lose.

A common informal budget is 3 dB for feedline loss. That’s already half your power gone. 6 dB is usually where problems become visible.

Using that lens:

- RG316 reaches 3 dB in just a few meters at 2.4 GHz

- RG58 reaches 3 dB around 4–6 m at 2.4 GHz

- LMR-400 can stay under 3 dB even past 12–15 m

This is why many real installations evolve toward a hybrid architecture: a short SMA jumper indoors, then a long, low-loss N-terminated outdoor feedline. That approach is discussed more broadly in our Coaxial Cable Ultimate Guide, where connector choice and cable loss are treated as a single system decision.

Setting realistic maximum lengths in Wi-Fi, LTE, and 5G systems

Practical guidance—not hard limits—looks like this:

- Wi-Fi 2.4 GHz

RG58 works for short rooftop runs, but LMR-400 quickly pays for itself beyond ~10 m.

- Wi-Fi 5 / 6 (5 GHz)

Loss climbs fast. RG58 becomes marginal even at moderate lengths. LMR-400 is usually the safe baseline.

- LTE / 5G Sub-6

Link budgets are tighter. Long sma to n cable runs should assume low-loss coax from the start.

When systems “almost” meet spec, the cable is often the silent culprit.

Which RF limits define the safe operating window for SMA to N cables and connectors?

Keeping the entire SMA–N chain strictly at 50 ohms

Most RF infrastructure operates at 50 Ω for historical and practical reasons. Mixing in 75 Ω components—sometimes unintentionally—introduces reflections that don’t always show up as total failure, but do show up as instability.

Wikipedia’s overview of impedance matching explains the principle clearly: mismatches create standing waves, raising VSWR and reducing effective power transfer.

In an SMA to N cable context, this means:

- 50 Ω coax

- 50 Ω SMA connectors

- 50 Ω N connectors

Even a single 75 Ω adapter hidden in the chain can degrade performance enough to matter at higher frequencies.

Checking frequency ratings for sma to n adapter and connector hardware

Between-series adapters often advertise impressive frequency ceilings—sometimes 6 GHz, sometimes 11 GHz or higher. Those numbers assume ideal conditions and short, rigid connections.

In real systems, frequency performance depends on:

- Mechanical tolerances

- Connector wear

- Assembly quality

This is why relying on “it looks like the right connector” is risky. Especially in Wi-Fi 6E or 5 GHz-plus systems, marginal connectors become visible much sooner.

For background on connector families and their frequency behavior, the Wikipedia page on the N connector provides useful historical and technical context without marketing noise.

Respecting power and voltage limits on SMA and N interfaces

Power handling is where SMA and N truly diverge.

- SMA connectors are compact, but their dielectric and pin geometry limit continuous power, especially at lower frequencies with high voltage swing.

- N connectors were designed for higher power and outdoor use, with larger contact areas and better heat dissipation.

Using a long RG316 SMA to N cable in a higher-power installation is a common mistake. The cable may survive electrically, but the SMA interface often becomes the weakest link—long before the N end shows stress.

How do you route and weatherproof SMA to N cables so they survive outside?

Keeping N connectors outside and SMA connectors inside

This principle is worth repeating because it works.

By keeping the SMA connector inside a cabinet, enclosure, or indoor space, you avoid exposing a fine-pitch interface to moisture and temperature cycling. The N connector, with its more robust design, handles the outdoor environment instead.

This approach mirrors recommendations found in general RF installation practices and aligns with guidance discussed in coaxial feedline references.

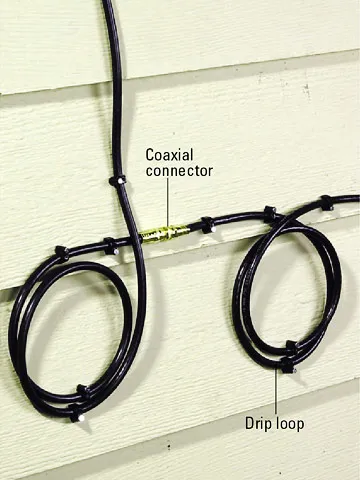

Applying proven weatherproofing methods at outdoor N joints

This instructional image addresses a critical field practice. It demonstrates how to properly seal outdoor N-type connections (like those on an SMA to N cable) against moisture ingress using materials like self-amalgamating tape and UV-resistant boots, which is essential for long-term reliability.

Even though N connectors are designed for outdoor use, secondary sealing dramatically improves longevity.

A typical field-proven sequence:

- Self-amalgamating (self-fusing) tape as the primary seal

- UV-resistant outer tape or boot

- Periodic inspection and re-sealing if needed

The goal isn’t to make the joint indestructible. It’s to slow water ingress enough that corrosion never gains a foothold.

Adding strain relief, drip loops, and bend-radius control

This diagram illustrates best practices for physically installing and routing cables outdoors. It shows how to form a drip loop to shed water away from connectors and how to secure the cable to prevent its weight from stressing the connector interface, both crucial for preventing weather and vibration-related failures.

Mechanical stress kills RF cables quietly.

Good installations usually include:

- Drip loops so water runs off before reaching connectors

- Strain relief so the cable’s weight doesn’t hang on the connector

- Bend radius control, especially for stiff cables like LMR-400

Ignoring these details often leads to intermittent faults that only appear during wind, rain, or temperature swings—the hardest kind to debug.

What recent deployment trends are quietly increasing demand for SMA to N cable assemblies?

If you look at recent RF projects—not datasheets, but real installations—the growth of sma to n cable usage feels almost inevitable.

Not because the connector itself changed, but because where radios are installed has changed.

RF hardware is moving outward, not upward

Traditional macro towers still exist, but much of today’s RF growth happens closer to the edge:

- Rooftop Wi-Fi coverage for campuses and warehouses

- Fixed wireless access (FWA) units mounted on buildings

- Private LTE / 5G nodes for factories and logistics sites

- Outdoor IoT gateways placed near sensors, not core racks

In these layouts, the radio is often protected indoors or inside a weather-rated cabinet, while the antenna must sit outside for coverage. That physical separation creates a recurring interface problem: SMA at the device, N-type at the antenna.

This pattern aligns closely with the historical division of RF connectors described in general references on RF connector families. SMA dominates compact device interfaces. N-type remains the workhorse for outdoor feedlines. The sma to n cable simply becomes the most practical bridge between the two.

Why low-loss outdoor coax is no longer “optional”

A decade ago, it was common to try a thinner cable first and “upgrade if needed.” That mindset has largely disappeared.

Modern systems operate with tighter link budgets. Higher modulation schemes, higher frequencies, and denser deployments leave less margin for guessing. As a result, installers increasingly default to low-loss coax—often LMR-400 class—for any outdoor run of meaningful length.

Once that decision is made, using a proper sma to n cable assembly becomes the cleanest option. It avoids the temptation to patch together adapters later, which almost always introduces more problems than it solves.

Fewer improvised fixes, more standardized cable kits

Another noticeable shift is how teams manage spares and replacements.

Instead of keeping bins of loose sma to n adapters, many organizations now standardize on a small set of cable assemblies: fixed lengths, fixed connector genders, fixed cable types. When something fails, the replacement is known in advance.

This approach doesn’t show up in marketing brochures, but it shows up clearly in maintenance logs.

How do you turn SMA to N cable requirements into something procurement can actually order?

Start by documenting the RF path, not the part number

Before selecting a cable, experienced teams usually document the path itself:

- Device port (SMA male or female)

- Antenna or arrestor port (N male or female)

- Operating bands and maximum frequency

- Approximate RF power

- Installation environment (indoor, rooftop, mast)

Putting this on paper—often in a simple table—immediately exposes mismatches. It also makes later discussions with suppliers much more efficient.

Use naming conventions that prevent accidental substitutions

Ambiguous names cause real-world mistakes. Clear ones prevent them.

For example:

- CBL-LMR400-SMAF-NM-10m-50R

- ADP-SMAF-NM-50R-6G

Even without a formal ERP system, this kind of naming makes it obvious whether someone is ordering a full sma to n cable or just an adapter.

A simple SMA–N cable loss & length planner

At this stage, most teams benefit from a quick estimation tool—not a simulator, just a guardrail.

Inputs

- Frequency band

- Cable type

- Length (m)

- Number of additional between-series adapters

Assumptions

- Cable attenuation based on typical published values

- Each extra adapter contributes ~0.1 dB of loss

Core calculation

- Cable loss = attenuation × length

- Connector loss = adapter_count × 0.1 dB

- Total feedline loss = cable loss + connector loss

This is a direct application of basic link budget principles, simplified enough to use during early planning or purchasing discussions.

The value isn’t mathematical precision. It’s preventing surprises.

When does a custom SMA to N cable become the sensible option?

This product photo exemplifies a custom cable solution. It likely shows a neatly assembled cable with specific length, connector types (SMA and N), and possibly a ruggedized jacket, representing the outcome when standard lengths are insufficient and a tailored assembly is ordered to fit exact mechanical and environmental requirements.

Custom cable assemblies are often treated as a last resort—something you do only when volumes are high or off-the-shelf options fail completely. In real RF projects, that assumption doesn’t hold up very well.

Most teams don’t move to a custom sma to n cable because they want something special. They do it because the standard options quietly start working against the system instead of with it.

Sometimes the signal is fine, but the cable routing is awkward. Sometimes the electrical margin looks acceptable on paper, yet the mechanical layout feels forced. Those are usually the early signs that a standard cable is no longer the best fit, even if it technically “works.”

Situations where standard lengths create more problems than they solve

This shift usually happens for practical reasons, not theoretical ones.

A custom sma to n cable often makes sense when:

- Excess cable length would need to be tightly coiled or bent to fit the enclosure or rooftop layout

- Connector orientation (straight vs. right-angle) determines whether the cable clears a wall, gland, or strain relief

- Outdoor exposure requires a specific jacket or additional mechanical support that standard assemblies don’t provide

- Multiple identical systems need repeatable routing so installation doesn’t become a one-off exercise each time

A small but common example: a standard 5 m cable technically fits, but leaves 1.5 m of unused slack near the entry point. That slack gets tied down, bent too tightly, or left to move in the wind. None of those outcomes are great long-term.

In cases like that, adapting a stock cable with extra sma to n adapters usually increases mechanical risk instead of reducing cost.

What to include when reaching out about a custom build

When teams do decide to request a custom sma to n cable, the most effective requests are usually the simplest ones.

At a minimum, it helps to specify:

- Cable type and impedance (for example, RG58 or LMR-400, 50 ohms)

- Exact length, based on the real routing path—not just straight-line distance

- Connector types, genders, and orientations at both ends

- Intended frequency range and approximate RF power

- Installation environment (indoor, rooftop, mast-mounted, temperature exposure)

A small, experience-based tip: measurements taken from an early mock-up or temporary install are often more reliable than enclosure drawings alone. Many custom cables are ordered after a first build for that reason.

Most teams already have this information in their system diagrams or installation notes. Reusing that material when contacting a supplier or technical support channel usually shortens the process and reduces back-and-forth.

What final checks keep SMA to N cable choices from turning into field failures?

Verify the fundamentals one last time

- Entire chain is 50 ohms

- Connector genders match the actual hardware

- Frequency rating comfortably exceeds operating band

These checks are basic, but they catch a large percentage of avoidable errors.

Decide where standardization actually helps

Capture field issues while they’re still fresh

This image shows another variant of the rigid adapter, this time with an N-type connector as the starting point. It's placed in the FAQ/closing section, likely as a reference for the specific component mentioned in questions about when adapters are acceptable (short, indoor transitions). It reinforces the distinction between adapters and full cable assemblies.

FAQ

How long can an SMA to N cable realistically be at 2.4 or 5 GHz?

It depends on cable type. RG58 becomes limiting quickly at higher frequencies, while LMR-400 supports much longer runs within typical loss budgets.

Is RG316 a good choice for permanent outdoor SMA to N installations?

Generally no. It’s better suited to short internal jumpers or high-temperature environments.

Can a 75-ohm N cable be reused in a 50-ohm system with an adapter?

Not recommended. Impedance mismatch introduces reflections and long-term reliability issues.

Where should a lightning arrestor be placed in an SMA–N feedline?

Typically on the outdoor N-type section, near the antenna or building entry point, with proper grounding.

When is an n to sma adapter acceptable instead of a full cable assembly?

Only for short, indoor transitions where environmental and mechanical stresses are controlled.

Closing perspective

A well-specified sma to n cable doesn’t stand out when everything works. That’s the point. It quietly preserves link margin, protects connectors, and removes variables that don’t need to exist.

Most “RF mysteries” aren’t mysterious at all. They’re the result of small architectural shortcuts taken early—and paid for later.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.