SMA to BNC Adapter Selection Guide for RF Labs

Jan 11,2026

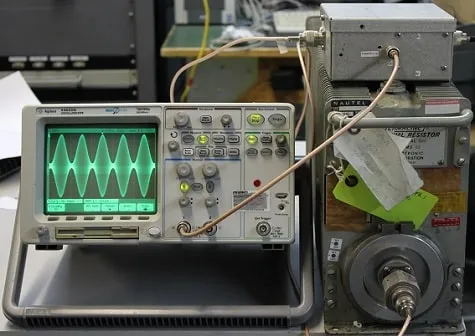

This opening graphic sets the stage by depicting an SMA to BNC adapter as a small, critical link in an RF measurement chain. It visually suggests that while the adapter is physically small and often overlooked, its quality and compatibility can be the hidden source of inconsistent or drifting measurement results.

In RF labs and radio projects, interface problems almost never announce themselves clearly. Signals still pass. Instruments still lock. Measurements look “reasonable enough” to move forward. Then someone touches the cable, rotates the adapter slightly, or swaps instruments—and the numbers shift.

In many of those cases, the root cause is not the radio, not the antenna, and not the instrument. It’s the small, usually ignored interface between them: the sma to bnc adapter.

This guide is written for engineers who already understand RF basics but want fewer surprises in real systems. It focuses on how sma to bnc adapter, bnc to sma adapter, and sma to bnc cable choices affect mechanical reliability, signal integrity, and long-term usability—especially in mixed lab and field environments.

Where does an SMA to BNC adapter actually sit in real RF and lab signal chains?

Map common paths between SMA-based boards and BNC-based instruments

This diagram illustrates the anatomy and application of a rigid gender adapter. It bridges the ecosystem mismatch: modern RF devices (with SMA jacks) and traditional lab instruments (with BNC ports). The description emphasizes material quality (brass, nickel/gold plating) and the mechanical torque mismatch this adapter must manage.

Modern RF hardware overwhelmingly exposes SMA ports. SDR boards, RF modules, evaluation kits, embedded radios, and wireless gateways almost all terminate in SMA female jacks. The reasons are practical: compact footprint, consistent impedance, and straightforward PCB integration.

Laboratory instruments, however, live in a different ecosystem. Oscilloscopes, spectrum analyzers, signal generators, and frequency counters still rely heavily on BNC connectors. They are robust, quick to connect, and mechanically forgiving—ideal for bench work.

This creates a very common signal path:

SMA-based device → sma to bnc adapter → BNC-based instrument

The adapter sits exactly at the boundary between two mechanical assumptions. On the SMA side, the connector is often board-mounted, lightly supported, and sensitive to torque. On the BNC side, the connector is usually chassis-mounted and designed to handle repeated mating and heavier cables.

That mismatch is why adapter choice matters more than it appears. When the wrong adapter is used, the SMA jack quietly absorbs forces it was never designed to handle. Over time, this shows up as intermittent contact, cracked solder joints, or subtle measurement drift that no amount of recalibration seems to fix.

If you’re already familiar with coax behavior across different RF cables, the same logic applies here. The adapter is part of the RF path, just like the cable. Treating it with the same level of intent avoids many downstream problems. For a broader view of how coaxial choices affect RF paths, the RG cable guide provides useful background that pairs well with adapter selection.

Separate pure SMA to BNC adapter roles from full SMA to BNC cable jumpers

This image visually contrasts the two main solutions for interface conversion. It supports the guide's argument: a rigid adapter is for stable, fixed connections, while a short flexible cable jumper acts as a mechanical buffer in environments with movement or misalignment, protecting delicate board-mounted SMA jacks.

Not every SMA to BNC conversion should be handled the same way. In practice, there are two distinct solutions that get lumped together:

- A rigid sma to bnc connector (solid metal adapter)

- A flexible sma to bnc cable, usually built with short RG316 coax

Rigid adapters are compact and inexpensive. They work well when equipment is fixed, alignment is clean, and the connection is rarely disturbed. On a stable bench setup—where the instrument and device remain in place for weeks—a single adapter is often sufficient.

Short cables serve a different purpose. They introduce flexibility into the system. In portable radios, teaching labs, or crowded benches where instruments are constantly moved, a short sma to bnc cable acts as a mechanical buffer. The coax absorbs motion instead of transmitting it directly into the SMA jack.

Many engineers default to rigid adapters because they appear “simpler.” In reality, cables often reduce long-term risk. This is especially true for board-mounted SMA connectors, which are not designed to carry sustained side loads. Similar tradeoffs are discussed in the context of SMA extension behavior in the SMA cable selection guide, and the same principles apply here.

Understand why adapter choice matters more at higher frequencies and tighter loss budgets

At low frequencies, almost any reasonable adapter will work. As frequency increases, small imperfections become measurable.

A typical high-quality bnc to sma adapter is designed for 50 ohm systems and rated somewhere between DC–3 GHz and DC–8 GHz, depending on construction. VSWR values commonly fall around 1.2:1 to 1.3:1. These numbers look small, and individually they are.

Problems arise when adapters are stacked or combined with long cables. Each interface introduces a small reflection. Each reflection adds to the overall mismatch. In wideband measurements or marginal RF links, this cumulative effect becomes visible.

Engineers often notice this first at 2.4 GHz or 5.8 GHz. The system still works, but noise floors rise slightly, calibration seems less stable, or repeatability degrades. In many cases, the root cause is not the radio or the instrument, but the chain of adapters quietly inserted between them.

How can you map SMA and BNC genders so the right adapter arrives the first time?

This photo showcases a specific gender configuration of adapter. It underscores the guide's critical point about avoiding gender ambiguity in specifications to prevent adapter stacking. This particular type (BNC female to SMA female) is less common but might be needed for specific instrument-to-instrument or device-to-device links.

Decode sma male to bnc female adapter use cases on scopes, generators, and analyzers

One of the most common adapter mistakes is gender ambiguity. Many BOMs simply say “SMA to BNC adapter” and assume the rest will sort itself out. It rarely does.

Consider a typical lab scenario:

- Instrument output: BNC male

- Device input: SMA female

The correct solution is a sma male to bnc female adapter. This creates a direct interface without additional gender changers or couplers.

If the wrong gender combination is ordered, engineers compensate in the lab by stacking adapters. The connection works, but the chain grows longer, heavier, and mechanically worse. What started as a one-piece solution turns into three parts, each adding loss and leverage.

This is why many teams now specify full gender and direction explicitly, especially when adapters are reused across projects.

Use sma female to bnc male adapter when reusing legacy BNC antennas and probes

Legacy equipment still has value. Many labs rely on older BNC antennas, probes, and fixtures that perform perfectly well within their intended frequency range.

When newer SDRs or RF boards expose SMA ports, the sma female to bnc male adapter allows that legacy hardware to remain useful. The key is understanding what you’re adapting.

Most RF SMA to BNC adapters maintain 50 ohm impedance. Many video-oriented BNC accessories are 75 ohm. The connector fits either way, but the system behavior does not. Quiet impedance mismatches often explain why “it works, but the numbers feel off.”

If your measurement chain is RF—not baseband video—confirm impedance before assuming compatibility.

Avoid gender chains that stack multiple SMA to BNC connector pieces together

This image serves as a warning example. It shows a messy, multi-piece adapter chain (e.g., BNC-SMA to BNC-SMA), which the guide identifies as a sign of mis-specification. Such chains introduce cumulative electrical discontinuities and create mechanical leverage that stresses connectors.

Every additional adapter in series adds two things: electrical discontinuity and mechanical leverage. A chain like BNC–SMA to BNC–SMA is almost always a sign that the original adapter was mis-specified.

In most cases, selecting the correct sma to bnc connector up front eliminates the need for stacking entirely. This simplifies the RF path, reduces stress on connectors, and improves repeatability.

If adapter chains are common on your bench, it’s worth stepping back and standardizing adapter types rather than continuing to compensate ad hoc.

When should you step up from a rigid SMA to BNC adapter to a short cable instead?

Compare stress and clearance between solid adapters and sma to bnc cable jumpers

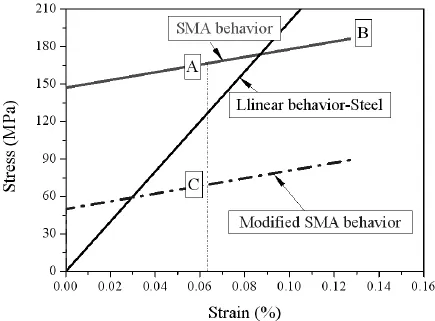

This technical graph, while mentioning "SMA" in the context of Shape Memory Alloy (not the connector), is used in the guide to analogize mechanical behavior. It likely illustrates how different materials (like a rigid adapter vs. a flexible cable) respond to strain (misalignment), supporting the argument for using flexible jumpers to absorb stress.

On paper, a rigid sma to bnc adapter looks ideal. It is short, direct, and electrically simple. In controlled bench environments, that is often true. The problem is that most real benches are not controlled environments for long.

In crowded racks, teaching labs, or field test setups, connectors rarely line up perfectly. Instruments are pushed back, radios are pulled forward, and cables get nudged during routine adjustments. A solid adapter turns every small misalignment into mechanical stress applied directly to the SMA jack.

A short sma to bnc cable changes that equation. The coax absorbs movement. The connectors stay aligned. The SMA jack no longer acts as a structural member.

This difference matters most on board-mounted SMA connectors. Unlike panel-mounted connectors, these jacks rely on solder joints and small pads for mechanical support. Repeated side loads do not usually cause immediate failure. Instead, they introduce micro-cracks that show up months later as intermittent behavior.

This is why many experienced labs quietly default to short cables whenever movement is expected. It is not about RF purity. It is about connector survival.

Choose appropriate coax (RG316, RG174, RG58) for sma to bnc cable assemblies

This photo presents the recommended flexible solution: a short, factory-assembled cable jumper. The guide discusses choosing the appropriate coaxial cable type (RG316, RG174, RG58) for such jumpers based on flexibility, loss, and application frequency.

Most SMA to BNC cable jumpers used in RF environments are built with 50 ohm coax. The differences between common cable types are practical rather than theoretical.

RG316 is the most common choice. It uses a PTFE dielectric, tolerates higher temperatures, and remains flexible over time. Its loss is higher than thicker cables, but acceptable for short runs at typical lab frequencies.

RG174 is thinner and more flexible, which helps in tight spaces. The tradeoff is higher attenuation, especially above 1 GHz. It works well for very short jumpers where clearance matters more than loss.

RG58 is thicker and mechanically robust. Its lower loss makes it attractive for longer runs, but its stiffness increases connector stress if used as a short jumper.

All three maintain 50 ohm impedance when properly constructed. The choice is less about “which is best” and more about matching handling, length, and frequency. If you need a refresher on how coax construction affects loss and flexibility across bands, the general overview in the coaxial cable article provides useful background without going into vendor-specific detail.

Set practical length limits so SMA to BNC cables don’t dominate your loss budget

Short cables are forgiving. Long ones are not.

In many RF labs, a working rule of thumb is simple:

- 0.3–0.5 m RG316: negligible impact below ~3 GHz

- Around 1 m: noticeable but often acceptable

- Beyond that: recheck the link budget

At 2.4 GHz, a short RG316 jumper typically introduces only fractions of a decibel of insertion loss. In most measurement and ISM-band applications, that does not meaningfully change results.

Where engineers get into trouble is assuming the same remains true as length increases. Once cables stretch past a meter—or when multiple adapters are added—the losses start to stack. At that point, it is worth revisiting attenuation data rather than relying on intuition.

The key idea is not to eliminate loss entirely, but to ensure the cable is not quietly consuming margin that the system cannot afford to lose.

How do RF specs like impedance, frequency, and VSWR limit your SMA to BNC options?

Keep 50 ohm impedance through sma to bnc connector and cable paths

Most RF SMA to BNC adapters are designed for 50 ohm systems. That aligns well with radios, SDRs, signal generators, and spectrum analyzers.

Confusion enters when BNC connectors from other domains are reused. In video and broadcast environments, 75 ohm BNC systems are common. The connectors mate mechanically with 50 ohm parts, but the impedance mismatch remains.

This mismatch does not always cause obvious failure. Signals still pass. Measurements still appear. The degradation shows up as subtle amplitude errors, frequency-dependent ripple, or inconsistent calibration.

If the system is RF-focused, the safest approach is to keep the entire path—device, adapter, cable, and instrument—at 50 ohms. For a broader explanation of why impedance consistency matters in RF systems, the overview in the impedance matching article provides a clear conceptual framework.

Check data sheets for DC–3 GHz vs DC–4 GHz vs DC–8 GHz adapter ratings

Not all bnc to sma adapter designs are equal. Frequency ratings vary significantly based on geometry, dielectric choice, and manufacturing tolerance.

Lower-cost adapters often specify DC–3 GHz. Mid-range designs extend to DC–4 GHz. Precision between-series adapters may be rated to DC–8 GHz or higher.

VSWR typically improves with higher-rated parts, especially near the upper end of their operating range. This matters in wideband measurements where flatness and repeatability are important.

Selecting an adapter rated just above your operating frequency is rarely sufficient. Margin matters, particularly when temperature, aging, and mechanical wear are factored in.

Consider power handling and voltage standoff when routing transmit signals through adapters

Adapters are passive, but they are not limitless.

Typical SMA to BNC adapters are rated for moderate RF power and voltage levels. This is adequate for receive paths, low-power transmitters, and most lab signal sources. Problems arise when higher-power transmit signals are routed through adapters that were never evaluated for that role.

Heat buildup, dielectric stress, and mismatch combine to shorten lifespan. In extreme cases, failure is not immediate but progressive, leading to unpredictable behavior over time.

If transmit power exceeds a few watts, it is worth reviewing adapter specifications carefully. Guidance from organizations such as the IEEE emphasizes the importance of derating passive components in RF power paths, even when connectors appear mechanically compatible.

What practices keep tiny board-mounted SMA jacks alive in a mostly-BNC world?

Use plug-saver sma to bnc adapter strategies on SDRs and handheld radios

This image demonstrates a practical reliability tip. It shows an adapter left semi-permanently on a sensitive, board-mounted SMA jack (like on an SDR). This sacrificial interface takes the wear and tear of frequent mating cycles, preserving the integrity of the more expensive and difficult-to-replace device port.

One quiet best practice in many labs is leaving an adapter or short cable permanently attached to sensitive devices.

Instead of repeatedly mating cables directly to a board-mounted SMA jack, engineers attach a sma to bnc adapter or short sma to bnc cable once and treat it as a sacrificial interface. Wear occurs on the adapter, not the device.

When the adapter loosens or degrades, it is replaced. The board survives.

This approach is especially common with SDRs and handheld radios that are frequently reconfigured during testing.

Support heavy BNC hardware so the SMA side never carries the load alone

BNC cables are thicker and heavier than SMA cables. Probes and adapters add mass. When that mass hangs directly from an SMA jack, the connector becomes a mechanical failure point.

Simple supports—clips, brackets, or cable ties—dramatically reduce stress. A short cable often serves the same role by decoupling weight from the connector.

This is not overengineering. It is respecting the mechanical limits of small RF connectors.

Label SMA to BNC cables and adapters to prevent silent impedance or gender mistakes

Many lab errors are not electrical. They are logistical.

Adapters look similar. Genders are easy to confuse. Impedance differences are invisible once connected.

Labeling adapters and cables reduces these mistakes. Color boots, laser markings, or even simple tags help teams reuse the correct parts consistently. The payoff is fewer measurement anomalies and less time spent debugging problems that are not really electrical at all.

Which industry trends are quietly increasing demand for sma to bnc adapter solutions?

Follow RF interconnect and RF connector market growth across telecom and aerospace

Connector adapters rarely get attention in market reports, yet they benefit from nearly every trend pushing RF systems forward.

Telecom infrastructure continues to densify. Aerospace and defense systems increasingly rely on modular RF subsystems. Medical and test equipment pushes toward higher bandwidth and tighter tolerances. Across these sectors, RF interconnect demand has shown steady growth over the past decade.

What matters here is not raw cable volume, but interface diversity. As platforms evolve faster than instruments, mismatched connector ecosystems become unavoidable. That is where between-series solutions like the sma to bnc adapter quietly scale.

Industry analyses on RF interconnect consistently highlight adapters as a faster-growing subcategory than bulk coax. The reason is simple: systems change interfaces more often than they replace entire signal chains. This aligns closely with broader discussions in the radio-frequency connector overview maintained by technical standards communities.

Note how SDR, education kits, and maker boards standardize on bundled SMA to BNC adapters

Another subtle signal comes from education and prototyping platforms.

Many modern SDR kits, university lab setups, and teaching-focused RF boards now ship with bundled SMA to BNC adapters or short jumper cables. This is not accidental. Designers know their boards will land in environments dominated by BNC instruments.

Rather than forcing users to improvise, vendors increasingly acknowledge that SMA on the device side and BNC on the bench side is the default hybrid model.

This normalization matters. Once adapters are assumed rather than optional, their selection quality directly affects user experience. Loose fits, poor VSWR, or mechanically fragile designs stop being edge cases and start becoming support issues.

Watch RF coaxial adapter segments grow faster than the broader coax market

While bulk coax demand tracks infrastructure investment cycles, adapter demand tracks system heterogeneity.

As RF systems span wider frequency ranges and mix legacy instruments with modern radios, adapters become permanent fixtures rather than temporary hacks. Market segmentation studies often point out that coaxial adapters—especially between-series types—outpace traditional cable growth in percentage terms.

In practice, this means adapter decisions deserve the same upfront attention as cable selection, not less.

How do you turn SMA to BNC choices into a clean, error-proof BOM and lab toolkit?

Capture port types, genders, and impedance in a single adapter line item

Most adapter mistakes originate in documentation, not design.

A line item that reads “SMA to BNC adapter” leaves too much to interpretation. By the time purchasing fills in the blanks, the engineering intent is already diluted.

A robust adapter description should include:

- Connector types on both ends

- Gender on both ends

- Direction (device side vs instrument side)

- Impedance (50 ohm)

- Frequency class (for example, DC–4 GHz)

This level of clarity eliminates adapter stacking and reduces rework during integration.

SMA to BNC Adapter & Cable Selection Matrix

This product photograph visually complements the selection matrix. It likely displays a range of physical solutions discussed in the guide, such as rigid SMA to BNC adapters and flexible cable jumpers with different connector genders (e.g., SMA male to BNC male). It serves as a tangible reference to help users identify and specify the correct component for their application, moving from abstract criteria to concrete product examples.

| Input Category | Example Value |

|---|---|

| Port A type & gender | SMA female on SDR board |

| Port B type & gender | BNC female on oscilloscope |

| Usage mode | Bench-fixed |

| Center frequency | 2400 MHz |

| Expected RF power | 1 W |

| Equipment movement | Rare |

Derived recommendation

- Item type: single sma to bnc adapter

- Gender combo: SMA male → BNC male

- RF risk score: Low

- Mechanical risk score: Low

| Input Category | Example Value |

|---|---|

| Usage mode | Portable / classroom |

| Equipment movement | Frequent |

| Center frequency | 915 MHz |

Derived recommendation

- Item type: 0.3–0.5 m sma to bnc cable

- Coax: RG316

- Mechanical risk score: Low

- RF risk score: Low

Risk scoring logic (simplified)

- Mechanical risk increases with rigid joints and movement

- RF risk increases with frequency, adapter count, and transmit power

The goal is not precision math, but consistency. When teams apply the same logic, adapter choices stop being ad hoc.

What SMA to BNC questions should your team answer before hardware and lab setups are frozen?

Decide which ports stay native SMA or BNC and which live behind adapters

Some ports should never see adapters. Others can tolerate them indefinitely.

Agreeing on this early prevents adapter creep, where temporary fixes become permanent without review. This mirrors broader system-integration principles described in engineering lifecycle discussions such as the systems engineering overview.

Agree on a standard SMA to BNC adapter kit for every bench, SDR, and field kit

Standard kits reduce friction.

Instead of scavenging adapters from neighboring benches, teams benefit from a defined set:

- A small number of sma to bnc adapter units

- A few bnc to sma adapter variants

- One or two short sma to bnc cable jumpers

Consistency improves repeatability and shortens setup time.

Capture recurring SMA to BNC issues as part of your project-specific FAQ

If the same adapter question comes up repeatedly, it belongs in documentation.

This prevents institutional knowledge from living only in one engineer’s memory and ensures new team members make the same decisions for the same reasons.

Frequently Asked Questions

Will a BNC to SMA adapter change the impedance of my test setup?

A properly designed adapter preserves 50 ohm impedance. Mismatch usually comes from mixing 75 ohm components.

How many SMA to BNC adapters in series are acceptable for RF measurements?

One is ideal. Two may be tolerable. More than that should trigger a redesign.

Can I use the same SMA to BNC adapters for radios and lab instruments?

Yes, as long as frequency and power ratings cover both applications.

Does a SMA to BNC cable introduce more loss than a simple adapter at 2.4 GHz?

Short RG316 cables typically add only fractions of a decibel and are acceptable in most cases.

Should student labs standardize on rigid adapters or cables?

Short cables with a plug-saver strategy generally survive better in teaching environments.

Final note

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.