SMA RF Cable: Length, Loss Planning, and Practical Design

Jan 13,2025

Preface

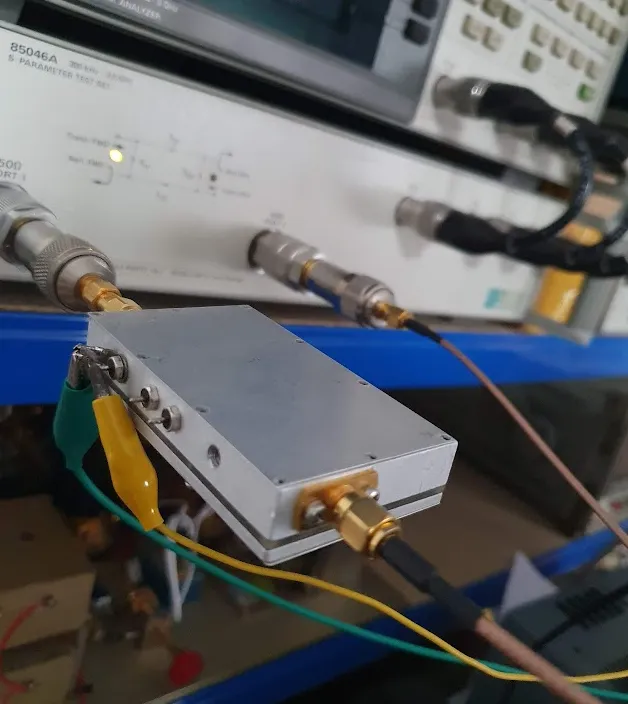

This opening graphic sets the thematic tone for the article. It likely uses a metaphorical or illustrative style (e.g., a cable in the background of a busy electronics scene) to convey the idea that SMA cables are frequently an afterthought in design reviews and system diagrams, yet their impact on real-world performance is significant and often only noticed when subtle issues arise.

An SMA RF cable usually enters a project quietly.

No one argues about it in early design reviews. It isn’t simulated with the same care as the antenna. It doesn’t get a block in the system diagram. Most of the time, it’s added after the radio works and the enclosure already looks finished.

That timing is the problem.

In the field, RF issues caused by SMA cables rarely look dramatic. Links don’t drop outright. Instead, range feels inconsistent. Throughput falls off earlier than expected. Measurements shift when someone touches the cable or reroutes it by a few centimeters. Everything is “almost fine,” which makes the root cause harder to pin down.

This article is written for engineers who have seen that pattern more than once. The goal isn’t to explain what SMA connectors are. It’s to look at how length, loss, and mechanical reality interact in SMA RF cable assemblies, especially in modern Wi-Fi, IoT, GNSS, and sub-6 GHz systems.

If you already work with coaxial cables broadly, think of this as a narrow, practical companion to general references like the RG cable guide. Same physics. Much tighter margins.

How should you position sma rf cable in your overall RF signal chain design?

Where does sma rf cable sit between chips, modules, feedlines, and antennas?

In real hardware, the sma rf cable almost never sits at a “clean” point in the RF path. It usually connects two things that were designed separately. A radio module on one side. An antenna, test instrument, or external RF box on the other.

A typical chain looks familiar:

RF chip or module → PCB transmission line → SMA connector → sma cable → antenna or equipment.

What’s easy to miss is that this cable is often the first removable RF element in the system. PCB traces are fixed. Antennas are usually selected and qualified. The SMA cable is the part people swap when debugging starts.

That makes it a diagnostic lever—and, unintentionally, a performance variable.

Once the RF path crosses a mechanical boundary (out of a shield can, through a panel, into free space), the sma rf cable becomes more than a jumper. It absorbs tolerance stack-ups, connector wear, and routing compromises that don’t show up in simulations.

Teams that treat SMA cables as part of the RF architecture—not just an accessory—tend to see fewer surprises late in the build.

How do sma cable runs differ between short internal jumpers and exposed antenna leads?

A 10 cm internal jumper and a 1 m antenna lead may look similar on a BOM, but they live very different lives.

Inside an enclosure, sma antenna cable runs are short and protected. Flexibility matters. Tight bends are common. Loss exists, but it’s rarely the limiting factor. Assembly speed and repeatability usually win.

Outside the enclosure, everything changes. Now the cable moves. It gets pulled during installation. It sees temperature cycles. The connector takes torque. In this role, the same thin cable that worked perfectly inside a router can become a long-term reliability risk.

This is why many experienced teams quietly maintain two mental categories:

internal SMA jumpers and external SMA antenna cables.

They may share connectors, but they don’t share priorities. Blurring that line is one of the easiest ways to accumulate hidden risk.

If your design pushes SMA cables through panels or toward external antennas, it’s worth aligning these decisions with antenna-focused guidance such as the SMA antenna cable selection guide, rather than treating everything as “just coax.”

When does the sma rf cable segment become the bottleneck in your RF budget?

At low frequencies, SMA cables are forgiving.

At higher frequencies, they are not.

At 900 MHz, you can often afford to be casual. At 2.4 GHz, that comfort shrinks. By 5–6 GHz, a meter of thin sma rf cable can quietly consume a meaningful chunk of your link margin.

This is where systems get fragile instead of broken.

The radio still transmits. The antenna still resonates. But small changes—cable routing, connector wear, even hand placement during testing—start to matter more than they should. When that happens, the cable is often the real bottleneck.

The key isn’t to avoid SMA cables. It’s to budget for them early, before enclosure geometry and antenna placement harden.

Which sma rf cable constructions make sense for different bands and enclosure constraints?

How do RG174, RG316, and RG58-based sma coax cable options compare in practice?

This visual comparison highlights the three most common coaxial cable families used in SMA assemblies. It likely contrasts their physical dimensions (thickness, flexibility), key material properties (dielectric), and summarizes their trade-offs: RG174 (thin, high loss), RG316 (balanced flexibility and temperature tolerance), and RG58 (thick, low loss). It reinforces the guide's message that these are not interchangeable choices and should be selected as part of frequency and mechanical planning.

Most SMA RF cable assemblies used in compact systems fall into three families: RG174, RG316, and RG58. All are nominally 50 Ω. All accept SMA connectors. That’s where the similarity ends.

RG174 is thin and easy to route. It fits where nothing else will. The trade-off is attenuation, especially as frequency climbs. RG316 improves consistency and temperature tolerance thanks to its PTFE dielectric, which is why it shows up so often in internal RF jumpers. RG58 is much thicker, but its lower loss per meter can buy back precious margin.

The mistake is assuming these choices are interchangeable. They aren’t. Engineers who treat cable family as part of frequency planning tend to make fewer late compromises.

If your organization already standardizes RG families using references like the RG cable guide, applying the same logic to sma coax cable assemblies keeps assumptions aligned across designs.

When is a slim sma coaxial cable worth the extra attenuation for tight spaces?

Slim sma coaxial cable is often chosen because there’s no alternative. Small IoT enclosures, automotive modules, and compact access points don’t leave room for thick coax.

In those cases, the decision isn’t wrong. It’s incomplete.

The difference between a stable design and a fragile one is whether the added loss was acknowledged upfront. If you knowingly trade margin for space—and compensate elsewhere—the system behaves predictably. If you ignore that trade, the cable becomes a silent constraint.

A good rule of thumb: if space forces a slim cable, treat the loss as a design input, not a post-hoc discovery.

How should connector grade and frequency rating steer your sma coax cable choice?

As systems move toward higher frequencies, connector quality stops being an afterthought. The sma rf cable is no longer defined only by copper and dielectric. Termination quality, tolerance control, and repeatability start to dominate.

Even designs operating below extreme frequencies are feeling this shift. Expectations shaped by high-frequency test equipment are pushing into everyday SMA assemblies. Better VSWR, tighter insertion loss spread, and clearer specifications are no longer “premium”—they’re baseline.

The practical takeaway is simple: cable and connector should be specified together. Treating them as independent parts is increasingly risky in modern RF systems.

How can you turn frequency and length into a concrete sma rf cable loss budget?

How do you read attenuation tables for sma rf cable at 900 MHz, 2.4 GHz, and 5–6 GHz?

Attenuation tables look harmless at first glance. A few numbers, usually expressed as dB per meter or dB per 100 meters. The problem isn’t the data itself—it’s how easily those numbers get mentally flattened across frequencies. Loss at 900 MHz and loss at 5 GHz do not scale linearly, even when the cable family stays the same. That behavior follows basic coaxial physics—skin effect, dielectric loss—which is summarized clearly in general references such as the overview of coaxial cable construction on Wikipedia.

What matters in practice is how fast those curves turn into real penalties once an sma rf cable leaves the datasheet and gets routed inside a product. For early planning, many teams rely on conservative, order-of-magnitude values rather than optimistic catalog numbers. The table below reflects the kind of approximations engineers actually use to avoid unpleasant surprises later.

| Cable family | ~900 MHz | ~2.4 GHz | ~5.8 GHz |

|---|---|---|---|

| RG174 | ~0.6 dB/m | ~1.1 dB/m | ~1.8 dB/m |

| RG316 | ~0.5 dB/m | ~0.9 dB/m | ~1.5 dB/m |

| RG58 | ~0.2 dB/m | ~0.4 dB/m | ~0.7 dB/m |

What link margin should you reserve specifically for sma antenna cable runs?

Experienced RF teams rarely leave SMA cable loss unbounded. Instead, they quietly assign it a fixed slice of the link budget early in the design. Not because the number is perfect, but because having a number forces discipline. Typical internal guidelines often look like this: sub-GHz systems keep cable loss comfortably under 1 dB; 2.4 GHz radios tolerate roughly 1–2 dB; 5–6 GHz designs often try to stay around or below 1.5 dB.

These aren’t universal limits. They’re guardrails. Once the sma antenna cable has an explicit allowance, decisions about length, routing, and cable family stop drifting. Without that boundary, cable loss tends to creep in small, invisible increments until margin disappears.

When should you upgrade from a single sma rf cable to a short pigtail plus low-loss feeder?

This diagram presents a best-practice solution for managing loss and mechanical stress in longer or higher-frequency runs. It visually separates the system into two segments: 1) a very short, flexible SMA cable (pigtail) directly connected to the device's sensitive SMA port, and 2) a longer, more robust, lower-loss feeder cable (like LMR series) that handles the majority of the distance and environmental exposure. This approach protects the board-mounted connector and optimizes overall link budget.

There’s a familiar moment in many projects when someone asks whether the SMA cable can simply be made longer. That’s usually the right time to step back. As frequency rises, extending a thin sma rf cable is rarely the cleanest solution. A more robust pattern is a very short SMA pigtail at the device, followed by a thicker, lower-loss feeder once the signal clears the enclosure.

This approach shows up repeatedly in RF installation practice and manufacturer guidance, including application notes from vendors like Times Microwave. Electrically, loss drops. Mechanically, stress moves away from the PCB connector. The limitation is timing—once enclosure geometry is frozen, this option may no longer exist, which is why it belongs in early planning rather than late fixes.

SMA RF Cable Loss & Margin Mini-Calculator

This mini-calculator isn’t meant to replace simulation or measurement. Its role is simpler: force a loss conversation early, before the cable becomes invisible. The inputs are frequency, cable family, length, and allowed loss. Attenuation per meter is pulled from an internal lookup table derived from published curves, then multiplied by length to estimate total loss. From there, the tool reports whether the cable fits the budget and back-calculates the maximum allowable length.

The value isn’t precision. It’s speed. It makes it immediately obvious when a seemingly small sma rf cable decision is already consuming margin the system can’t spare.

How do connector genders and end styles drive your sma rf cable assembly choices?

When should you specify a sma male to sma male cable versus other end pairs?

This is a standard product photo of an SMA male-to-male cable. The guide recommends this configuration as the cleanest solution when connecting two SMA female ports (common on RF instruments and many modules). It minimizes the number of interfaces, reduces potential for tolerance stacking and adapter-related losses, and simplifies lab troubleshooting.

This product photo shows an SMA male-to-female cable. The guide highlights its utility in scenarios like extending an antenna connection or feeding a signal through a panel bulkhead. This gender combination allows for a direct, adapter-free connection when one side has a female port (e.g., on a device) and the other side requires a male connector (e.g., for an antenna or bulkhead), preserving mechanical simplicity and electrical integrity.

Where does a sma male to sma female cable make antenna extensions cleaner?

How do straight, right-angle, and bulkhead ends change enclosure routing options?

What mechanical, thermal, and EMC rules keep sma rf cable runs out of trouble?

How tight can you safely bend sma coaxial cable without hurting long-term reliability?

How should you anchor sma antenna cable so torque never lands on tiny SMA pads?

What jacket and shielding choices matter in noisy or high-temperature environments?

How are market trends and new RF applications reshaping sma rf cable requirements?

Why is the RF coaxial cable assemblies market growing faster than general cabling?

One quiet shift over the past decade is that RF cable assemblies are no longer treated like generic wiring. They’re increasingly specified as functional RF components. Market analyses tracking RF coaxial cable assemblies consistently show higher growth rates than general-purpose cabling, largely because wireless systems are spreading into places where performance margins are thinner and tolerances tighter.

What’s driving this isn’t volume consumer electronics alone. It’s infrastructure density. More radios per device. More bands per product. More test points per system. Every one of those trends increases the number of short, pre-terminated RF interconnects. In many of those paths, sma rf cable assemblies become the most flexible way to bridge subsystems without redesigning PCBs.

The practical implication for engineers is subtle: expectations are rising. Assemblies that were once considered “good enough” now get scrutinized for repeatability, connector consistency, and documented performance limits.

How do precision >18 GHz assemblies push the limits of sma rf cable design?

At the extreme end of the spectrum, precision RF assemblies above 18 GHz often migrate to interfaces like 2.92 mm or similar. Yet the influence doesn’t stop there. Requirements from those environments—tight VSWR control, stable insertion loss, consistent phase behavior—are bleeding into high-quality SMA assemblies as well.

Even when systems operate well below those frequencies, customers and test engineers increasingly expect SMA cables to behave predictably across temperature, handling, and repeated mating cycles. The result is that sma rf cable design today is less forgiving of sloppy termination or loosely controlled cable stock than it was ten or fifteen years ago.

This isn’t about chasing laboratory-grade perfection. It’s about reducing variability in systems that already operate close to their margins.

How are 5G, IoT, and experimental research quietly increasing sma rf cable usage?

Not all growth comes from obvious places. In 5G and IoT deployments, SMA-terminated cables show up everywhere—inside gateways, in small cells, and in test setups used to validate radios before deployment. These cables are short, numerous, and often treated as disposable, yet their collective impact on system behavior is significant.

Outside commercial products, research environments also rely heavily on SMA cabling. Timing distribution, RF reference routing, and experimental setups in physics and communications research frequently use sma rf cable for its balance of bandwidth and convenience. Publications and lab notes shared through platforms like arXiv and ResearchGate show this pattern repeatedly, even when it isn’t the focus of the experiment itself.

The common thread is modularity. SMA cables make systems easy to reconfigure. That flexibility, however, increases the need for predictable behavior.

How can you standardize sma rf cable BOMs, tests, and documentation across projects?

What fields should every sma rf cable assembly line item include in the BOM?

Ambiguity is the enemy of repeatability. A well-specified sma rf cable line item removes guesswork before procurement ever starts. At minimum, experienced teams tend to lock down cable family, finished length, connector type and gender on both ends, connector orientation, impedance, frequency rating, jacket material, and intended use (internal or external).

These fields aren’t about bureaucracy. They exist because changing any one of them can subtly change RF behavior or mechanical reliability. Writing them down once saves repeated clarification later.

How do you define a simple incoming test routine for sma rf cable lots?

Not every cable warrants full RF characterization. For many production environments, a tiered approach works better. Visual inspection and dimensional checks catch obvious issues. DC continuity and insulation tests catch assembly errors. For higher-risk applications, spot-checking VSWR or insertion loss on a sample basis adds confidence without slowing the line.

The key is consistency. Even a simple test routine, applied the same way every time, dramatically reduces the chance that a marginal sma rf cable slips into a system unnoticed.

How can you document reference builds so future sma rf cable changes are low-risk?

Teams that ship multiple generations of hardware often keep a “golden” cable assembly on hand. Along with drawings and test notes, this physical reference becomes a baseline. When suppliers change or cable stock evolves, comparisons stay grounded.

This habit doesn’t eliminate risk, but it makes changes intentional rather than accidental.

Which recurring sma rf cable questions should your team settle before release?

Have you frozen maximum allowed cable loss per band and product family?

Do you have a standard sma antenna cable kit for labs, pilots, and field builds?

How will you capture sma rf cable issues into your next design checklist and FAQ?

FAQ

How long can a thin SMA RF cable like RG174 realistically be at 5 GHz before loss becomes painful?

In practice, even short runs add up quickly at that frequency. Many engineers start questioning RG174 once lengths approach a few tens of centimeters and use quick loss estimates to decide whether to step up in cable size.

Is it better to run one continuous SMA RF cable or break it into a short pigtail plus a thicker feeder?

For longer distances or higher frequencies, a short SMA pigtail followed by a lower-loss feeder usually performs better electrically and mechanically. The trade-off is planning effort, not performance.

Can I reuse the same SMA RF cable assemblies for both lab testing and field deployments?

You can, but many teams choose not to. Lab cables see frequent mating and bending. Field cables see environmental stress. Separating them reduces unexpected aging effects.

What is a reasonable loss budget to assign specifically to SMA antenna cable in a small IoT device?

It depends on band and link margin, but many designs aim to keep cable loss well below the realized antenna gain so the cable doesn’t negate antenna improvements.

How tight is “too tight” when bending an SMA coaxial cable inside a compact enclosure?

Meeting the published minimum bend radius is rarely enough near connectors. Applying a 2×–3× margin near SMA terminations significantly improves long-term reliability.

Do SMA male-to-male and male-to-female RF cables behave differently at high frequency?

When properly built, electrical differences are minimal. The real differences are mechanical—routing flexibility, adapter count, and how much stress ends up on the connector.

What information should I include so a vendor can build the exact SMA RF cable I need?

Cable family, length, connector gender and orientation on both ends, frequency rating, jacket material, temperature range, and whether the cable is used internally or externally. Clear specifications prevent silent substitutions.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.