SMA Male to Female Cable Extension Guide

Jan 22,2025

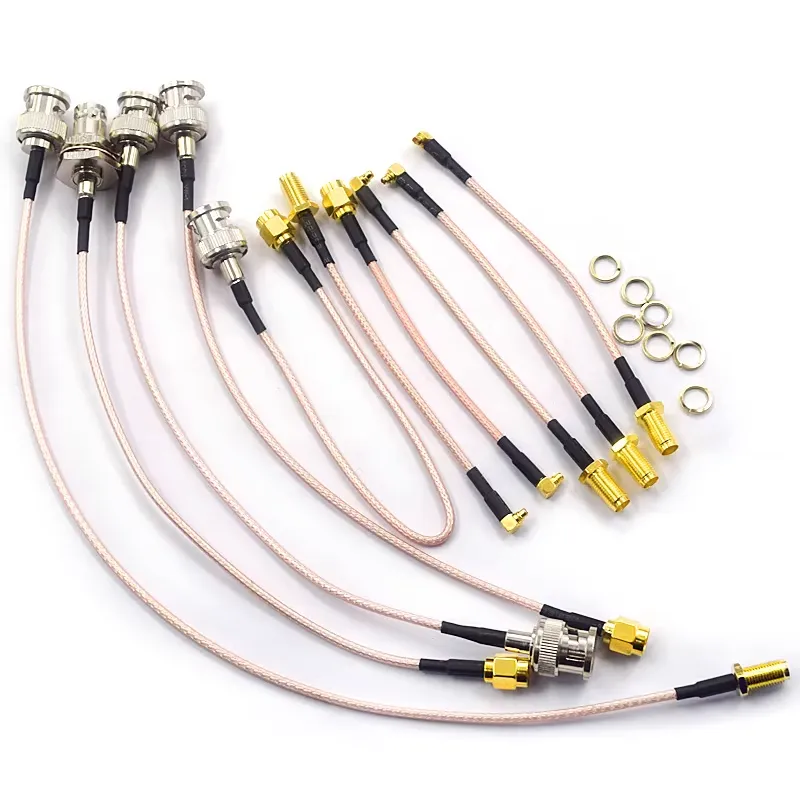

This image appears at the beginning to visually introduce the core argument—the importance of this cable lies in its long-term value of mechanical protection, not instantaneous electrical parameters. It might be a contrasting image: the left side shows an ideal RF testing scenario (a clear spectrum or stable S-parameters), symbolizing “initial good performance”; the right side shows a close-up of a slightly worn SMA female connector with changed metal luster due to frequent mating, symbolizing “mechanical degradation over time.” An SMA male-to-female cable bridges the two sides,暗示 its role is to isolate mechanical wear and protect the “pure” performance on the left. This echoes the text: “The link still worked… But performance drifted. Connectors loosened.”

Where does an sma male to sma female cable actually help in RF systems?

If you look back at most RF projects that aged poorly, the failure usually wasn’t dramatic. The link still worked. The radio still powered up. But performance drifted. Connectors loosened. Touching the cable changed readings just enough to be annoying.

That’s usually when someone realizes the cable choice was never really thought through.

The sma male to sma female cable sits in that exact gray zone. It looks trivial. It behaves passively. It’s easy to treat it as just another sma cable and move on. In practice, it often decides where mechanical stress lives in the system—and that matters more than most people expect.

This cable rarely fixes RF problems. It prevents mechanical ones from turning into RF problems later.

Why a male-to-female SMA extension behaves differently than a normal jumper

Following the subheading “Why a male-to-female SMA extension behaves differently than a normal jumper,” this should be a clear comparison schematic. The left side shows a standard Male-to-Male SMA jumper connecting two fixed SMA ports (e.g., on two PCBs), emphasizing its “linking” function. The right side shows an SMA Male-to-Female cable: its male end connects to a module depicted inside an “enclosure”; its female end extends outside the enclosure, exposed, with a hand shown connecting or rotating an antenna next to it. Arrows clearly indicate Torque and Side Load applied to the exposed female end, and a “wear” icon or annotation points there, visually explaining how this cable redefines the stress path and wear location.

A standard SMA jumper, typically male-to-male, connects two known endpoints. Both sides already define the interface. The cable just links them.

A sma male to sma female cable quietly changes that assumption. One end disappears into the system. The other end becomes the place where hands, tools, and antennas interact with the hardware.

That means the extension defines:

- where torque is applied,

- where side-loads occur,

- and which connector is expected to wear out first.

This difference doesn’t show up in S-parameters. It shows up a year later, when an SMA jack feels loose or intermittent. Engineers who’ve had to replace damaged SMA connectors tend to be more cautious here, especially once they understand how plug and jack designs age differently under real use. That distinction is covered well in discussions like this breakdown of SMA plug vs jack behavior and torque limits, and it’s the reason many teams stop treating male-to-female extensions as interchangeable with jumpers.

On the bench, both look the same. In the field, they don’t behave the same at all.

Three ways these cables actually get used

In real hardware, sma male to sma female cables almost always end up in one of three roles, even if the BOM doesn’t say so.

Sometimes it’s just an extension. The RF module stays buried inside the enclosure. The female end is moved outside so the antenna can be connected without stressing the board. Nothing fancy. This is common in routers, gateways, and SDR boxes.

Sometimes it becomes a panel feed-through. The female end is fixed at the enclosure wall. The male end connects internally to a module or a short coax. At that point, the cable is part of the mechanical design. Vibration, thermal movement, and assembly tolerances all matter. Engineers who already plan panel cutouts and grounding tend to lump these extensions mentally into the same category as bulkhead hardware.

And sometimes it’s used purely for instrument protection. Labs rarely document this, but it’s everywhere. A short sma male to sma female cable lives permanently on a spectrum analyzer or VNA. It takes the abuse. When it wears out, it gets replaced. The instrument connector stays untouched. This habit usually forms after someone has paid for a front-panel repair once.

Problems start when one cable SKU is expected to serve all three roles equally well. That usually works at first—and degrades quietly over time.

Where the sma rf cable extension really sits in the signal path

If you sketch the RF path instead of listing parts, the extension’s role becomes obvious:

RF module → short internal coax → sma male to sma female cable → antenna or instrument

That short segment decides where stress ends. Too short, and stress reaches the module jack. Too stiff, and the cable becomes a lever. Too long, and you add loss and routing problems for no reason.

Most engineers are comfortable estimating loss on an sma rf cable. Fewer stop to ask how that same cable behaves mechanically once the enclosure is closed and someone starts tightening connectors. Drawing the extension explicitly on the diagram tends to surface those questions early.

How should you choose length and cable type for sma male to sma female cables?

Think in length ranges first

This image is located in the “How should you choose length and cable type for sma male to sma female cables?” section. It is likely an infographic that systematizes the selection process. The chart might be divided into two parts. Top part: Divided into three columns by length, e.g., “Very Short (0.1-0.2 m)”, “Medium (0.2-0.5 m)”, “Longer (0.5-1.0 m)”, each with icons of typical applications (e.g., circuit board, test equipment, outdoor unit). Bottom part: Lists cable families (RG316, RG174, LMR-100, LMR-200) with concise icons or text describing their characteristics (e.g., “Flexible/Heat-tolerant”, “Ultra-thin/Easy routing”, “Low-loss/Stiffer”). Arrows or lines connect the application scenarios above with the recommended cable types below, possibly annotating key trade-offs (e.g., “Loss vs. Stiffness”). This image is a visual embodiment of the text’s advice to “think in length ranges first” and then “choose cable family.”

Across real products and lab setups, most sma male to sma female cables fall into a few buckets.

Very short runs, roughly 0.1–0.2 m, are common for board-to-panel transitions. They keep loss negligible and don’t introduce much leverage. Once installed, they’re almost invisible.

Mid-length runs, around 0.2–0.5 m, show up everywhere. Lab instruments. Desktop enclosures. Internal routing where a little slack prevents tight bends.

Longer runs, roughly 0.5–1.0 m, appear when connectors need to move for accessibility or thermal reasons. At this point, both loss and stiffness start to matter more.

Teams that lock exact lengths before deciding which bucket they’re in usually revisit the choice later, once strain relief and bend radius become real constraints.

Choosing the sma coax cable family

Once the length range is clear, cable family selection stops being abstract.

RG316 is a common default for short and medium extensions. It tolerates heat, bends reasonably well, and behaves predictably. Loss is higher than thicker cables, but manageable when kept short.

RG174 is thinner and easier to route. The tradeoff is attenuation, which climbs quickly with length. It’s best kept short and used where power levels are modest.

LMR-100 and LMR-200 offer lower loss per meter and make sense for longer extensions or tighter budgets. Their stiffness means they need support, or they’ll transfer stress directly to the SMA jack.

These are the same tradeoffs engineers already consider when selecting other RF jumpers. Many teams keep extension choices consistent with their broader coax strategy, often leaning on internal rules similar to those discussed in references like RG vs LMR cable selection for RF jumpers.

Loss expectations that actually hold up

Every extension adds loss. At 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz, a common working guideline is to keep extension loss under 3–4 dB, unless that penalty is explicitly budgeted.

This isn’t a spec limit. It’s a reminder. Radios and antennas are often tuned tightly. An unplanned sma rf cable extension can quietly reduce margin without tripping any obvious alarms during validation.

A lightweight selection matrix teams actually use

Some teams formalize extension selection with a simple matrix—not to over-engineer it, but to avoid repeating the same debates.

Inputs

| Item | Note |

|---|---|

| Use_case | Lab / Panel / Outdoor CPE / Router / Industrial |

| Frequency_GHz | Primary band |

| Required_length_m | Approximate |

| Max_extra_loss_dB | System budget |

| Expected_mating_cycles | Low / Medium / High |

| Environment | Indoor / Outdoor / Vibration / Temperature |

Quick check

Estimated_loss = Loss_per_meter × Required_length

Remaining_margin = Max_extra_loss − Estimated_loss

If the margin is healthy, the choice is fine.

If it’s tight, shorten the cable or step up to a lower-loss family.

If it’s negative, redesign early.

That’s usually enough to keep sma male to sma female cable choices sane across multiple projects.

Can you treat sma male to sma female cables as sacrificial extensions for instruments?

Most labs already do this. They just don’t always admit it in documentation.

Front-panel SMA connectors on spectrum analyzers, signal generators, and VNAs are not designed to be abused. They’re precise, expensive, and mounted to panels that were never meant to take constant side loads. Yet in day-to-day lab work, those connectors see exactly that: repeated connect-disconnect cycles, cables hanging at odd angles, adapters stacked on adapters.

This is where the sma male to sma female cable quietly becomes a protective component.

Why short extensions protect instruments better than adapters

Following the subheading “Why short extensions protect instruments better than adapters,” this should be a real lab scene photo. The focus is on the front panel of a Vector Network Analyzer (VNA) or Spectrum Analyzer, with a short, high-quality SMA Male-to-Female cable permanently attached to one of its SMA female ports. To emphasize its “sacrificial” nature, one or two old, worn-out cables of the same type with cracked jackets or loose connectors might be casually placed in the foreground, contrasting with the new cable on the instrument. An arrow or label might point out “Daily wear happens here” (old cable) and “Instrument port protected” (instrument panel). This image visually demonstrates a common but often undocumented best practice in labs.

Adapters look tempting. They’re rigid. They feel solid. They’re also unforgiving.

A rigid SMA adapter transfers torque and side load directly into the instrument jack. A short sma male to sma female cable, especially one using a flexible sma coax cable, does the opposite. It decouples motion. When someone bumps the cable or over-tightens slightly, the extension absorbs most of that stress.

Many labs standardize on short extensions—often in the 0.2 to 0.3 m range—and leave them permanently attached. The extension becomes the wear item. When it degrades, it gets replaced. The instrument stays untouched.

This practice aligns well with how connector mating cycles are typically specified in connector standards and summarized in references like the general overview of RF connectors. The takeaway is simple: connectors are not infinite-life components. Something has to wear first. Better that it’s the cable.

Stiffness matters more than loss in this role

For instrument protection, loss is rarely the limiting factor. Stiffness is.

A very low-loss but rigid cable can behave like a lever arm hanging off the front panel. Over time, that constant bending moment works against the SMA jack’s mounting hardware. A slightly higher-loss but more flexible sma coaxial cable often performs better mechanically, even if it looks worse on paper.

This is one of those cases where chasing the lowest attenuation number actively makes the system worse.

When sacrificial extensions should be mandatory

Some teams formalize rules around this after learning the hard way. Common triggers include:

- High-value instruments where connector repair is costly or slow

- Setups with frequent reconnects during calibration or production testing

- Shared labs where many users handle the same equipment

In those environments, a sma male to sma female cable stops being optional. It becomes part of the lab infrastructure, treated more like a consumable than a precision component.

Designing sma male to sma female cables for panel feed-through and enclosure transitions

Panel feed-through use looks straightforward on a schematic. In hardware, it rarely is.

Once a female SMA interface is exposed at an enclosure wall, the extension cable behind it becomes part of the mechanical load path. That changes how you should think about both the cable and the enclosure.

Panel interfaces are mechanical systems first

When a sma male to sma female cable terminates at a panel, the female end usually becomes the user-facing connector. Every antenna swap, every torque event, every vibration cycle passes through that interface.

At that point, the cable behind the panel is no longer “just wiring.” It defines how load is transferred into the enclosure. If the internal leg is too short, stress concentrates at the internal SMA jack. If it’s too stiff, vibration travels straight into the RF module.

Engineers who already think about enclosure grounding, sealing, and panel hardware tend to recognize this early. Those who don’t often discover it later, after intermittent failures appear.

Internal routing mistakes show up months later

Inside the enclosure, the internal leg of the sma coax cable is easy to underestimate. Sharp edges, tight bends, and pinch points rarely cause immediate failure. Instead, they create slow degradation.

Common mistakes include:

- Routing across unfinished metal edges

- Allowing the cable to be compressed by lids or brackets

- Ignoring minimum bend radius near the connector body

None of these typically fail during bring-up. They fail after vibration, shipping, or seasonal temperature changes. When that happens, the symptom often looks like RF noise or instability, not a mechanical fault.

RF and power harnesses should not be casual neighbors

Another recurring issue is proximity to power wiring. A sma rf cable running parallel to high-current harnesses over long distances invites coupling. The result is rarely catastrophic. Instead, noise creeps in just enough to reduce margin.

Good practice is boring but effective: separation where possible, short parallel runs where unavoidable, and deliberate grounding points when the environment is electrically noisy. These are the same principles outlined in broader electromagnetic compatibility discussions such as electromagnetic interference, applied at the enclosure level rather than the PCB.

Keeping sma male to sma female cables mechanically reliable over time

Torque control is not optional, even if it feels that way

SMA connectors tolerate less abuse than many users assume. Over-tightening doesn’t improve RF performance. It accelerates wear.

Clear guidance helps: whether tools are allowed, what torque range is acceptable, and where users should grip the connector. Telling installers to “tighten by feel” works only until it doesn’t.

Strain relief does more than tidy cables

A simple clamp or tie-down near the panel can dramatically extend connector life. The goal is not cosmetic. It’s to redirect load away from the SMA interface and into the cable jacket or enclosure structure.

This matters most for longer sma male to sma female cables, where the cable’s own weight becomes a constant load.

Validation should include motion, not just measurements

During validation, it’s worth doing something unglamorous: gently moving the cable while monitoring continuity or RF parameters. If performance changes with small movements, something is already wrong.

Catching that behavior early prevents field failures that are far harder to diagnose.

Aligning sma male to sma female cable SKUs with real RF system needs

A common long-term problem in RF product lines is that extension cables are treated as filler SKUs. They get added late, named inconsistently, and grouped by part number logic rather than by how they are actually used. That approach often survives early product launches, but it rarely survives scale. As systems expand across routers, gateways, outdoor CPEs, and lab setups, the same sma male to sma female cable ends up exposed to very different mechanical and environmental conditions. When expectations are unclear, small cable differences turn into field issues, inconsistent behavior, and avoidable returns.

Grouping extension cables by use case instead of catalog structure tends to work better. A lab instrument extension has different priorities than a panel feed-through inside an industrial enclosure. A sacrificial cable meant to absorb daily mating cycles does not need the same stiffness or environmental margin as one expected to sit behind a sealed panel for years. When SKUs are defined around scenarios—lab, panel, outdoor, high-temperature—the selection conversation becomes simpler. Engineers stop debating edge cases and start choosing cables based on what they are designed to survive.

SMA’s continued dominance in the roughly 1–6 GHz range reinforces this approach. The interface persists not because it is trendy, but because it is predictable. Tooling, mating behavior, and failure modes are well understood. As a result, sma male to sma female cable assemblies continue to be ordered as infrastructure rather than experimental components. Teams that already maintain internal SMA connector rules often extend the same logic to extensions, keeping assumptions consistent with broader coax practices such as those outlined in Coaxial cable structure, shielding and impedance basics.

Field replacement practices that actually reduce downtime

Treating extension cables as first-class components has a practical side effect: faster troubleshooting. In field diagnostics, replacing a sma male to sma female cable is often the quickest isolation step. It is inexpensive, fast, and reversible. Many intermittent RF issues—especially those triggered by movement, vibration, or temperature—disappear immediately once a worn extension is swapped out. Teams that document this explicitly in service procedures avoid unnecessary antenna, module, or radio replacements.

Spare planning works best when it reflects environment rather than theory. Installations with vibration, frequent reconnection, or rough handling justify higher spare ratios. Static indoor systems rarely do. Aligning spare quantities with actual stress conditions reduces both downtime and inventory waste, and it reinforces the idea that extension cables are consumables, not permanent fixtures.

FAQ

When should I choose an sma male to sma female cable instead of a male-to-male jumper?

Use a male-to-female extension when you want to relocate the interaction point of the RF system. Typical cases include panel feed-throughs, protecting internal SMA jacks, or creating a defined user-accessible connector while keeping the original port inside the enclosure.

Does adding an sma male to sma female cable always hurt RF performance?

Any additional cable adds some loss and another interface, but the impact is usually small when the extension is short and the cable family is chosen correctly. Most real-world issues associated with extensions are mechanical rather than purely electrical.

Is it reasonable to leave sma male to sma female cables permanently attached to test equipment?

Yes. Many labs intentionally leave short extensions attached to instruments as sacrificial interfaces. They absorb mating wear and mechanical stress, protecting the more expensive front-panel connectors.

Which cable types are best for panel feed-through extensions?

For short internal runs, flexible options such as RG316 are commonly used because they tolerate bending and temperature well. For longer feed-throughs or tighter loss budgets, lower-loss cables like LMR-100 or LMR-200 can be appropriate when properly supported.

Can a worn extension cable affect VSWR or stability?

Yes. Wear near the connector, micro-motion damage, or repeated over-tightening can all shift VSWR slightly. Swapping the extension is often the fastest way to determine whether the cable is contributing to unstable readings.

What information should be labeled on an sma male to sma female cable?

At minimum, label the frequency band, length, and cable family. Clear labeling helps installers and technicians distinguish lab extensions, panel feed-throughs, and outdoor cables without referring to documentation.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.