SMA Female to BNC Male: Direction, 50Ω Matching & Bench Applications

Dec 01,2025

Figure serves as the visual anchor for the entire article. By presenting a realistic lab scene, it allows readers (especially engineers) to quickly engage with the technical context. The soft lighting and depth of field emphasize professionalism and practicality, laying an intuitive foundation for the subsequent in-depth discussion of adapter technical details.

It’s easy to underestimate how much a small adapter defines an entire signal chain.

A simple SMA female to BNC male piece looks harmless, but get the direction wrong and the waveform on your scope might never show up.

Every RF engineer eventually learns this lesson — sometimes the hard way — when a test setup quietly refuses to behave because of one flipped interface.

These adapters sit at the intersection of two connector worlds: threaded SMA ports used on high-frequency modules, and bayonet-locked BNC connectors found on oscilloscopes and analyzers.

Their job sounds simple — bridge those two standards while keeping a perfect 50-ohm match — but the geometry, gender, and even the order of connection matter far more than you’d think.

If your lab uses oscilloscopes, signal analyzers, or RF evaluation boards, you’ll likely need one of these adapters.

They show up everywhere — from 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi prototypes to automotive EMI tests — linking delicate SMA jacks on DUTs to the robust BNC inputs on measurement gear.

And yet, one misplaced order or a swapped direction can throw the entire measurement budget off.

Are You Sure You Need SMA-F to BNC-M in This Chain?

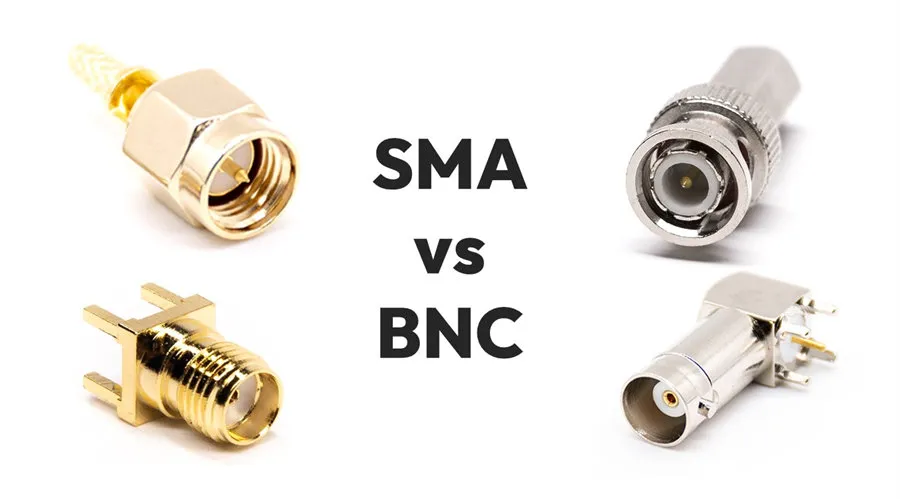

Figure addresses a common yet error-prone issue in RF connections—directionality. It translates the abstract concepts of “gender” and “direction” into an intuitive mapping diagram, helping engineers avoid mistakes caused by interface confusion when planning signal chains or purchasing, emphasizing the precision of technical documentation.

It sounds like a trivial detail — SMA female to BNC male — but this direction decides whether your signal ever reaches the instrument.

On every RF bench, there’s a quiet rule: never assume connector direction until you’ve looked twice at both gender and thread type.

The SMA side uses threaded coupling, where the female jack has external threads and a central hole; the BNC side, by contrast, secures with a quick bayonet twist and a male center pin.

Mix them up once, and you’ll end up forcing mismatched parts or stacking extra bnc to sma adapters, which only add loss and instability.

Before you order, verify three simple but critical things:

- Port gender — SMA female (hole) or SMA male (pin).

- BNC side — male plug or female jack.

- Signal flow — instrument to cable to DUT, or the reverse.

A common trap: both ports are female — for example, a scope’s BNC-F front end connected to a module’s SMA-F jack.

That combination actually calls for a BNC male to SMA male adapter, not the SMA-F to BNC-M type.

One small mismatch like that can create a cascade of confusion later in procurement and calibration.

If your setup involves multiple instruments, take a moment to sketch a port-mapping table — instrument end, cable end, and DUT end — marking each as “M” or “F.”

You’ll catch errors long before they cost you test time.

A veteran engineer once joked that half of all “RF signal issues” start as “RF gender issues.”

He wasn’t wrong.

Consistency saves both time and money.

At TEJTE, engineers maintain a standardized port map across all benches:

- Scopes and analyzers to BNC-F ports

- Modules and DUTs to SMA-F jacks

- Adapters and jumpers to bridge between them

Following that logic, every chain makes visual sense — and nobody reaches for the wrong adapter mid-test.

If you’re unsure which direction matches your hardware, refer to TEJTE’s SMA–BNC adapter series for verified direction codes and drawings before placing an order.

Verify “port gender vs. pin/hole” and direction before ordering

In purchasing documents, the line “SMA Female to BNC Male (50 Ω)” should never be abbreviated to “SMA-BNC.”

That shorthand hides directionality and gender — the most common cause of wrong shipments.

If you’re working with offshore procurement teams, always attach a photo or drawing.

Even better, add a checklist field:

| Field | Example | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | SMA-F to BNC-M | Match exact port genders |

| Impedance | 50 Ω | Avoid 75 Ω video BNC |

| Orientation | Straight | or Right-Angle |

| Cable family | RG316, RG58 | Choose based on frequency & loss budget |

| Length | 0.3 m / 0.5 m / 1.0 m | Keep short for stability |

Map instrument BNC ports to DUT SMA jacks without stacking adapters

In a perfect setup, you’d have one interface from scope to DUT.

Yet labs often accumulate adapter chains like a mechanical Jenga tower:

BNC-M to SMA-F to SMA-M to cable to SMA-F to DUT.

Every interface adds 0.05–0.2 dB loss at 1 GHz — small individually, but destructive when you’re chasing ±0.5 dB budgets.

Instead, plan your bench around minimum transitions.

Use a direct SMA to BNC cable assembly when possible.

Not only does it simplify routing, but it also improves repeatability during calibration.

TEJTE’s coaxial cable assemblies provide off-the-shelf SMA to BNC combinations pre-tested for 50 Ω match and mechanical torque.

If you frequently swap modules, color-code the cables (gray for scope, blue for DUT) and tag the direction — you’ll thank yourself later.

How Do You Keep a True 50-Ω Match from Scope to DUT?

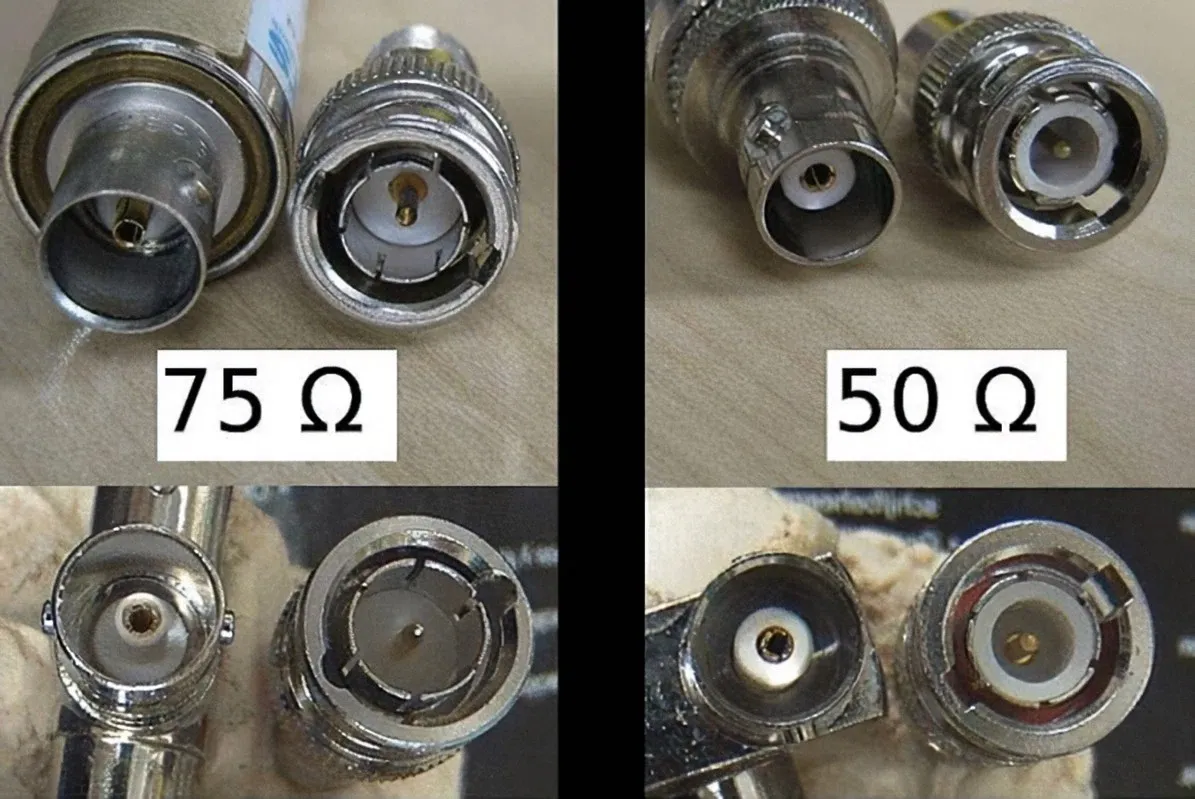

Figure is an important technical warning graphic. It visually explains the root cause of impedance mismatch, the “silent killer.” The comparative format allows readers to instantly understand the importance of choosing the correct cable. The accompanying waveform schematic visualizes the abstract concepts of reflection and loss, effectively enhancing the article's instructional value.

In the RF world, impedance mismatch is a silent killer.

When your 50-ohm chain includes even one stray 75-Ω BNC lead, the reflection ratio (Γ) jumps to 0.2 — that’s about 1.7 dB of mismatch loss.

You might not see it on the oscilloscope, but your calibration drift and measurement repeatability will.

That’s why all BNC cables on an RF bench must be explicitly marked “50 Ω”.

Video cables — those used for CCTV or broadcast — are almost always 75 Ω, and their thinner dielectric causes higher mismatch above 1 GHz.

In test and measurement (T&M) applications, mixing them is never worth the temporary convenience.

Don’t mix 75-Ω video BNC in RF benches; spot-and-replace checklist

To audit your setup, trace the signal from the instrument to the DUT:

- Inspect each cable jacket — “RG-58” or “RG-59”? (The latter is 75 Ω.)

- Check connector labels — some adapters are dual-impedance, and that’s a red flag.

- If you see unknown brands or broadcast leftovers, replace them.

Here’s a quick visual reminder:

| Cable Family | Impedance | Common Use | Replace If Found |

|---|---|---|---|

| RG58 | 50 Ω | Lab / RF test | Keep |

| RG316 | 50 Ω | Compact / Flexible | Keep |

| RG59 | 75 Ω | Video / CCTV | Replace |

| RG6 | 75 Ω | Long-distance video | Replace |

Small mismatches accumulate — one 75 Ω lead might shift your S-parameter baseline or distort rise-time measurements beyond tolerance.

Many labs now implement annual connector audits, labeling all 50 Ω chains with yellow heat-shrinks.

Use short 50-Ω jumpers when the bench is frequently reconfigured

Every time you rearrange instruments, you risk stretching coax runs or twisting connectors.

For benches that change daily, short 0.3 – 0.5 m jumpers with flexible coax (RG316 or RG223) maintain return loss under 25 dB even after hundreds of cycles.

Longer or stiffer cables (like RG58) tend to torque the BNC barrels and loosen SMA threads over time.

Engineers often underestimate how much mechanical stress degrades the signal chain.

At TEJTE’s test labs, SMA female connectors that survived a year of constant swapping show visible thread wear when overstressed.

A smart approach is to reserve a fixed “reference jumper set” for calibration only, and separate the “daily use” cables for experiments.

Adapter or Cable — Which Is Cleaner at 2.4 / 5 GHz?

Adapters are seductive — small, cheap, and instantly available.

But above a few gigahertz, every adapter behaves like a small cavity resonator.

The insertion loss may still read 0.1 dB on paper, yet its phase ripple and return loss degradation can be ten times more damaging than the spec sheet suggests.

So the rule of thumb:

- For static setups (fixtures, rarely moved): a good BNCT to SMAF adapter works fine.

- For dynamic benches (frequent re-patching): use a short SMA to BNC cable assembly instead.

When a 0.3–0.6 m SMA to BNC cable beats a plug-in adapter

Figure focuses on solution selection in engineering practice. It goes beyond simple component display to the level of system configuration. By juxtaposing two common practices, it guides readers to consider the optimal choice for different application scenarios (static fixture vs. dynamic test bench), reflecting a design mindset that moves from part recognition to system optimization.

Imagine a network analyzer connected to a DUT board through a single adapter.

It looks clean, until vibration or cable weight shifts the SMA port sideways.

A 0.5 m jumper acts as a mechanical buffer — absorbing strain while preserving electrical length.

Here’s a comparative view based on TEJTE’s RG316 assemblies (at 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz):

| Configuration | Length | IL @ 2.4 GHz | IL @ 5 GHz | Return Loss | Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Adapter | 0 m | 0.08 dB | 0.12 dB | 28 dB | Poor (rigid) |

| 0.3 m Jumper (RG316) | 0.3 m | 0.18 dB | 0.29 dB | 30 dB | Excellent |

| 0.5 m Jumper (RG316) | 0.5 m | 0.28 dB | 0.46 dB | 28 dB | Good |

| 1.0 m Jumper (RG316) | 1.0 m | 0.52 dB | 0.83 dB | 26 dB | Fair |

Notice how the loss grows linearly with length, yet the mechanical stability increases dramatically.

In practice, the 0.3 – 0.5 m range gives the best compromise between loss and repeatability.

When a BNCT to SMAF adapter is acceptable (low-movement fixtures)

Figure returns from the application scenario to the product itself. The white-background close-up has the quality of product photography, highlighting the device's craftsmanship and reliability. It conveys a message to readers: in scenarios where adapters are acceptable, choosing a product with fine craftsmanship and solid materials, as shown in the picture, is the foundation for ensuring RF performance.

For stationary test fixtures — where cables aren’t constantly moved — adapters still make sense.

A high-quality 50 Ω adapter with gold-plated contacts maintains return loss better than 25 dB up to 6 GHz.

The key is to avoid mixing old and new adapters; oxidation and micro-scratches accumulate small mismatches.

TEJTE’s SMAF-BNCM units, for example, use precision-machined brass with nickel or gold finish and meet MIL-STD mechanical torque specs.

They’re rated up to 500 mating cycles, ideal for semi-permanent connections between panels and instruments.

That said, even the best adapter can’t rescue a bad chain.

Always count interfaces:

one interface = one reflection source.

Keep it under three from instrument to DUT for high-frequency measurements.

Will Right-Angle vs Straight Ends Change Results?

Right-angle and straight connectors don’t just change cable geometry — they change how mechanical stress distributes across your setup.

When a BNC male is inserted into a crowded oscilloscope front panel, side-loads can twist its bayonet lock, slightly altering contact pressure.

At high frequencies, even that tiny movement modifies return loss by a few dB, particularly on older scopes with loose jack tolerances.

Straight connectors provide the shortest electrical path.

Their benefit shows up above 5 GHz, where phase consistency and minimal parasitics matter.

However, straight ends protrude further and often force the cable to bend sharply.

That bend can be worse than the connector difference itself — a tight 15 mm radius on RG316 may induce 0.1 dB additional loss per turn.

Right-angle connectors, by contrast, relieve mechanical strain.

They make the setup neater, reduce leverage on the BNC barrel, and often survive hundreds of insertions without loosening.

In many TEJTE bench trials, the SMA female to BNC male right-angle assemblies maintained the same 0.3 dB insertion loss at 2.4 GHz as their straight counterparts — but they lasted 40 % longer under repeated flexing.

So which should you choose?

If your bench has fixed rack instruments, go straight for pure electrical fidelity.

If you’re frequently re-patching or working inside compact enclosures, go right-angle and save the ports from mechanical fatigue.

Strain Relief and Side-Load on BNC Barrels

Every oscilloscope port suffers eventually from side-torque.

A heavy coax hanging vertically creates constant leverage.

Right-angle ends distribute this load horizontally, preventing wear on the internal bayonet spring.

For SMA interfaces, strain relief collars or flexible boots add similar protection.

At TEJTE, technicians often add a small loop near the connector — a gentle cable arc acts like a spring and isolates micro-vibrations.

Such practices aren’t glamorous but directly extend connector life and measurement stability.

Mechanical integrity and RF integrity are two sides of the same coin.

Panel Clearance vs Return-Loss Budget Trade-offs

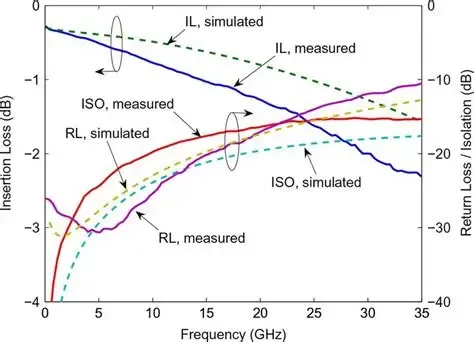

Figure elevates the article's technical discussion to the level of quantitative analysis. The graph provides trends of key performance parameters, enabling readers to make decisions based on data rather than just rules of thumb. The annotation of “PASS/FAIL” regions in the graph is particularly practical, directly linking theoretical curves to engineering budgets. It is a powerful tool for guiding design verification and fault diagnosis.

When working with rack panels or compact test fixtures, right-angle BNC connectors solve clearance issues.

They route cables cleanly, but they also introduce slightly longer internal pin transitions.

At frequencies below 3 GHz, the difference is negligible (< 0.05 dB).

At 6 GHz and beyond, some adapters exhibit an extra 0.1–0.2 dB insertion loss.

Still, engineers accept this small penalty to maintain safety margins and mechanical convenience.

If your return-loss budget allows > 24 dB, the trade-off is perfectly reasonable.

The key is consistency: don’t mix straight and right-angle parts randomly within the same calibration path.

How Long Can the Run Go Before IL and Ripple Show Up?

Loss scales almost linearly with length — but ripple, reflections, and phase errors don’t.

They build up once the total electrical length approaches a significant fraction of the wavelength.

At 5 GHz, one wavelength in RG316 (velocity factor ≈ 0.7 c) equals about 42 mm.

A 0.5 m cable already contains more than ten wavelengths, so any mismatch turns into standing-wave ripples on your trace.

Engineers often use a rule-of-thumb insertion-loss budget:

keep total IL below 1 dB between the scope and DUT at your working frequency.

That includes cable attenuation, connector losses, and mismatch losses.

Below is a simplified loss summary based on TEJTE’s tested RG316 and RG58 assemblies (50 Ω):

| Length (m) | RG316 @ 2.4 GHz | RG316 @ 5 GHz | RG58 @ 2.4 GHz | RG58 @ 5 GHz |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.3 | 0.18 dB | 0.29 dB | 0.10 dB | 0.17 dB |

| 0.5 | 0.28 dB | 0.46 dB | 0.16 dB | 0.28 dB |

| 1.0 | 0.52 dB | 0.83 dB | 0.30 dB | 0.52 dB |

| 2.0 | 1.00 dB | 1.62 dB | 0.60 dB | 1.04 dB |

You can see how RG58 stays slightly lower in loss thanks to its thicker conductor and dielectric, but RG316 wins in flexibility and routing space.

At 5 GHz, keeping runs under 0.5 m is ideal unless you compensate with better cable families (e.g., RG223 or low-loss PTFE types).

Presets for 0.3 / 0.5 / 1.0 m with RG316 / RG58 Families

| Preset | Frequency Range | Recommended Cable | IL Target (dB) | Return Loss (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Bench | ≤ 3 GHz | RG316 | ≤ 0.3 | ≥ 28 |

| Standard Bench | ≤ 5 GHz | RG316 / RG58 | ≤ 0.5 | ≥ 26 |

| Long Run | ≤ 2 GHz | RG58 / RG223 | ≤ 1.0 | ≥ 24 |

Such presets simplify BOM management and calibration.

Procurement teams can simply pick a preset code — for example “SMA-F to BNC-M, RG316, 0.5 m, 50 Ω” — and every unit will perform identically.

You can reference compatible assemblies directly from TEJTE’s RF coaxial cable line.

Keep Interface Count Low; Torque Notes for Repeatability

Each mated pair adds roughly 0.1 dB insertion loss and a possible 1 dB return-loss degradation.

In a chain with four interfaces, that’s already 0.4 dB lost before considering cable attenuation.

More critical than the number itself is repeatability — loose SMA torque changes VSWR unpredictably.

Follow a consistent torque range (typically 0.8–1.1 N·m for SMA) using a torque wrench.

BNC connectors don’t use torque, but ensure the bayonet click feels firm; too loose means degraded contact, too tight indicates wear.

When calibrating VNAs or oscilloscopes, re-tighten all SMA ends each session and label any that feel rough.

Mechanical feel often predicts RF stability.

Can You Estimate Insertion / Return Loss in Two Minutes?

Many engineers delay validation until the signal looks wrong.

But a quick estimation can tell you if your chain is within budget — without ever touching a VNA.

A simple calculator or spreadsheet, like the one below, lets you check whether your SMA female to BNC male path still meets your loss and return-loss targets.

At TEJTE, internal teams often use this mini-planner before committing to a test build.

It models cable attenuation, connector loss, and mismatch reflection, producing an instant Pass/Fail verdict.

SMA-F to BNC-M Direction & Match Planner

| Input Fields | Example | Unit / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 5 | GHz |

| Length | 0.5 | m |

| Cable Family | RG316 | RG316 / RG58 / RG223 |

| Interface Count | 3 | adapters + cable ends |

| Per-Interface Loss | 0.10 | dB @ 1 GHz |

| VSWR | 1.20 | - |

| Loss Budget | 1.0 | dB |

| Return-Loss Target | 25 | dB |

Formulas

| Parameter | Formula | Description / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Cable Loss (dB) | α family (f) × Length | Frequency-dependent attenuation of the cable (e.g. RG316 ≈ 1.6 dB/m @ 5 GHz) |

| Interface Loss (dB) | Interface Count × IL if | Sum of connector or adapter losses (typically 0.05–0.20 dB @ 1 GHz per interface) |

| Mismatch Loss (dB) | −10 · log10(1 − ρ2) | ρ = (VSWR − 1)/(VSWR + 1); represents reflection from impedance mismatch |

| Total Insertion Loss (dB) | Cable Loss + Interface Loss + Mismatch Loss | Overall signal attenuation along the SMA-BNC chain |

| Return Loss (dB) | 20 · log10((VSWR + 1)/(VSWR − 1)) | Measures impedance-matching quality — higher = better |

| Pass Condition | IL total ≤ Loss Budget AND Return Loss ≥ Target | System passes when both thresholds are satisfied |

Example Calculation

At 5 GHz using RG316 (α ≈ 1.6 dB/m):

- Cable Loss = 1.6 × 0.5 = 0.8 dB

- Interface Loss = 3 × 0.10 = 0.3 dB

- Mismatch Loss = 0.043 dB

Total IL = 1.14 dB to FAIL (above 1 dB budget)

At the same frequency with RG223 (α ≈ 1.1 dB/m):

- Cable Loss = 1.1 × 0.5 = 0.55 dB

- Interface Loss = 0.3 dB

- Total IL ≈ 0.85 dB to PASS

This two-minute evaluation keeps every bench consistent.

Before you finalize any SMA-F to BNC-M order, fill these fields once and confirm the numbers line up with your budget.

Actions: Shorten Run / Reduce Adapters / Upgrade Cable Family

If your chain fails the quick test, three corrective levers exist:

- Shorten the cable. Each 0.1 m reduction in RG316 saves ~0.16 dB at 5 GHz.

- Reduce interfaces. Replace stacked adapters with one direct SMA–BNC jumper.

- Upgrade cable family. Move from RG316 to RG223 or low-loss PTFE coax.

These small tweaks often recover 1 dB or more of headroom — enough to clean up ringing and flatten S-parameter sweeps.

This process takes less time than re-running a full calibration and pays off in more predictable measurements.

What’s New in T&M That Pushes Cleaner SMA to BNC Practices?

Modern test and measurement gear keeps raising bandwidth ceilings, forcing engineers to revisit their once-safe connector habits.

New oscilloscopes and VNAs expose every mismatch that older 1 GHz setups would have hidden.

Here’s a look at what’s changed across major manufacturers.

Keysight 1.6 T Optical Sampling Scopes: Bandwidth Exposes Tiny Mismatch

Keysight’s optical sampling family (e.g., 1.6 T-bit analyzers) pushes frequency coverage into multi-hundred-GHz ranges.

At these speeds, even a 1 mm discontinuity can distort signal edges.

Keysight’s own app notes emphasize that shorter RF paths and single-impedance chains are now mandatory.

For everyday engineers, it means using single-adapter or short-jumper solutions — the same rule this guide promotes.

SIGLENT SDS5000X HD: More Channels, Stricter Organization

With 8-channel, 1 GHz scopes like the SIGLENT SDS5000X HD , bench density is increasing.

Each extra channel multiplies the need for compact 50-Ω jumpers over rigid adapter stacks.

TEJTE’s SMA-to-BNC short cables keep instruments accessible while maintaining phase alignment.

RIGOL DS80000: Multi-GHz Workflow and Mechanical Stability

RIGOL’s DS80000 series extends bandwidths up to 13 GHz .

At those levels, mechanical alignment matters as much as electrical design.

Loose BNC barrels or mis-torqued SMA threads introduce reflections that appear as false harmonics.

Hence, most high-speed labs now adopt dedicated SMA–BNC assemblies tested to ±0.1 dB repeatability.

Anritsu ShockLine VNA: Faster Sweeps, Earlier Fault Detection

The ShockLine VNA series supports simultaneous port sweeps, so any mixed-impedance link reveals itself instantly during calibration.

A single 75 Ω segment creates a visible dip, saving time before full test runs.

Such tools reinforce the discipline — standardize on 50-Ω SMA to BNC paths and minimize transitions.

The Trendline: Precision T&M Rewards Discipline

Across all brands, one pattern repeats: as bandwidth climbs, interconnect discipline becomes performance.

Details like direction, torque, and cable family define measurement credibility.

That’s why modern procurement forms — like those used at TEJTE — embed these parameters directly.

A 30-second check at order time prevents hours of debug later.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How do I verify I’m buying SMA-F to BNC-M and not the reverse?

Check gender and direction carefully: SMA female = outer thread, central hole; BNC male = plug with center pin.

Add this line to every PO: “Direction: SMA-F to BNC-M (50 Ω, straight).”

2. When is a short SMA to BNC cable better than a plug-in adapter?

If your bench changes often, a 0.3–0.6 m jumper is mechanically and electrically better than a rigid adapter.

Loss difference is minor (~0.2 dB), but repeatability and strain relief are far better.

3. My BOM says “BNC STR plug / SMA STR plug / 0.25 m” — what does it mean?

Both ends are straight plugs, one BNC plug and one SMA plug, with 0.25 m of 50-Ω coax.

Confirm port genders — many instruments use BNC female and DUTs use SMA female, so a male-to-male jumper is needed.

4. Can I mix a 75-Ω BNC lead temporarily?

5. Can I order SMA-F at the DUT and BNC-M at the scope with color-coded boots?

6. Does a right-angle BNC end add significant loss at 5 GHz?

7. What’s the practical max length at 5 GHz on RG316?

Closing Note

The difference between a good and great RF measurement often hides in the connectors.

Choosing the correct SMA-F to BNC-M direction, maintaining a pure 50-Ω chain, and controlling length, torque, and strain aren’t details — they’re fundamentals.

With modern scopes reaching multi-GHz bandwidths, even 0.1 dB mismatch can distort reality.

When in doubt, check direction twice, plan the chain, and lean on reliable assemblies from trusted sources like TEJTE’s RF Adapter & Cable Series.

Your waveforms — and your calibration logs — will thank you.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.