SMA Cable Use in RF Links and Antennas

Feb 15,2026

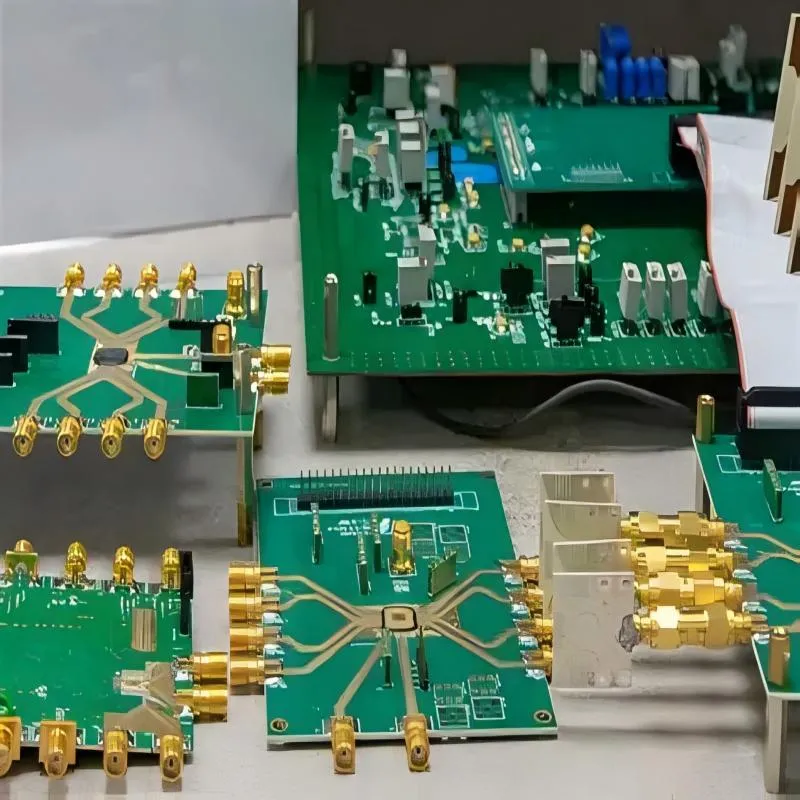

This introductory figure sets the stage for the entire guide. It likely shows a typical SMA-terminated coaxial cable assembly. The surrounding text explains that SMA cables rarely get attention—they don't amplify, filter, or radiate—yet they are often the root cause of RF issues blamed on antennas or radios. Loss grows over time, measurements shift when cables are touched, and field links fade after installation. The image visually introduces the component that, if treated as a commodity rather than a design element, quietly becomes the weakest link.

An SMA cable is one of those RF components that almost never gets the spotlight. It doesn’t amplify, filter, or radiate. It simply connects things that already “work.” And yet, across lab benches, rooftops, vehicles, and factory floors, it quietly shapes link margin, repeatability, and long-term reliability.

Most RF issues blamed on antennas or radios eventually trace back to the interconnect. Loss that grows over time. Measurements that shift when a cable is touched. Field links that look solid on paper but fade after installation. In many of those cases, the SMA-terminated coaxial assembly was treated as a commodity rather than part of the RF design.

This article takes a different angle. Instead of treating SMA cable as a generic accessory, it looks at how it behaves inside real RF links—how it interacts with RG316 coaxial cable, MMCX connectors, adapters, and antennas—and how to plan its use deliberately rather than reactively.

Why does SMA cable sit at the center of so many RF links?

Treat sma cable as a design decision, not a last-minute accessory

This figure visually illustrates the timing problem the guide addresses. It likely shows a design timeline where cable selection occurs late in the process, after critical decisions have already been made. The surrounding text warns that once a cable becomes permanent—mounted through a panel, routed along a chassis, or bundled into a harness—its loss, phase stability, and mechanical limits become fixed constraints. Changing it later means reworking metal, retesting compliance, or touching firmware. The image helps engineers recognize that treating cable as a design element early avoids this trap.

In a typical RF project, the cable decision shows up late. By the time an engineer reaches for an SMA jumper, the RF IC has already been selected, the antenna tuned, and the enclosure roughly defined. Early tests pass. The link closes. Nothing appears broken.

That sequence creates a blind spot. Once a cable becomes permanent—mounted through a panel, routed along a chassis wall, or bundled into a harness—it stops being flexible in both senses of the word. Its loss, phase stability, and mechanical limits become fixed constraints. Changing it later often means reworking metal, re-testing compliance, or touching firmware that was never meant to change.

Treating sma cable as a design element early avoids that trap. It forces questions that are easy to ignore at bring-up: How long is this run really going to be? Will it be moved or flexed in the field? Is this jumper part of a measurement path or part of the shipped product? Those answers matter far more than the connector type printed on the bag.

Map where sma cable appears: lab jumpers, antenna leads, internal harnesses

One reason SMA cable is underestimated is that it shows up in so many roles. On a bench, it’s a short jumper between a signal generator and a DUT. In a gateway, it’s an antenna lead exiting a metal enclosure. Inside a product, it might be a short internal harness bridging an RF module to a bulkhead connector.

Electrically, all of these are 50-ohm coaxial paths. Mechanically and operationally, they are completely different. A lab jumper might be mated hundreds of times. An antenna cable might never be disconnected after installation but must survive vibration and weather. An internal harness may be bent tightly and then left untouched for years.

When all of these are treated as “the same SMA cable,” it becomes difficult to reason about failure modes. Separating these roles conceptually—and often with different part numbers—helps prevent subtle issues later.

Understand 50-ohm RF chains vs mixed-impedance video or control paths

SMA connectors strongly imply a 50-ohm RF environment. Problems arise when that assumption leaks into mixed systems. It’s common to see test setups or field installations where RF, video, and control signals coexist physically, sometimes even sharing adapters.

A 75-ohm video coax with an SMA adapter may “work” in the sense that a signal passes, but reflections and return loss creep in quietly. Over short distances, the impact may be small enough to ignore. Over longer runs or higher frequencies, it becomes measurable.

Clear separation between true RF paths and everything else makes SMA cable behavior predictable. When an SMA-terminated assembly is used, the rest of the chain should be unambiguously 50 ohms—connectors, adapters, and cables included.

Map your RF signal path and locate every SMA cable segment

Trace the path from RF IC to antenna and mark each cable & connector

A simple but effective exercise is to trace the RF path end-to-end, starting at the RF IC output pin and ending at the antenna. Every transition belongs on that map: PCB launches, connectors, adapters, cables, bulkheads, and feed-throughs.

When engineers do this carefully, they often discover more transitions than expected. A short internal cable that was forgotten. An adapter added “temporarily” during testing that never got removed. A connector pair hidden behind a panel.

Each of those transitions contributes loss and reflection. Individually, the numbers look small. Together, they shape the usable margin of the link.

Separate short “jumper” sma coax cable runs from long feeder lines

Length changes everything. A 20-cm sma coax cable jumper between instruments behaves very differently from a 5-meter antenna run mounted on a mast. Short jumpers tolerate higher attenuation per meter because the absolute loss stays small. Long feeder lines do not.

Mixing these two use cases under the same assumptions leads to mistakes. A cable that is perfectly acceptable on the bench may quietly dominate the loss budget once it becomes part of an outdoor installation. Treating jumpers and feeders as separate categories avoids that confusion.

Tag segments that might use rg316 coaxial cable or other thin coax families

This figure likely depicts thin coaxial cable families, with RG316 as a prominent example. It appears in the section discussing how to tag segments that might use RG316 or other thin coax. The surrounding text acknowledges that in dense hardware, these cables often feel like the only option that physically fits. However, it also highlights the trade-off: at higher frequencies, RG316's loss per meter is significantly higher than thicker coax. The image makes this compromise visible, turning an implicit assumption into an explicit design consideration.

Thin coax families such as rg316 coaxial cable exist for good reasons. They are flexible, easy to route, and compatible with compact connectors. In dense hardware, they often feel like the only option that physically fits.

The trade-off is attenuation. At higher frequencies, RG316’s loss per meter is significantly higher than that of thicker coax. Tagging these segments explicitly during planning makes it easier to revisit them later when margins get tight. It turns an implicit compromise into a visible one.

For a deeper look at how RG316 behaves electrically and mechanically, see RG316 Coaxial Cable Specs, Loss & Uses.

How do SMA cable, RG316, and MMCX cable differ in practice?

Compare sma cable vs rg316 cable vs other 50-ohm coax families

This figure shows a specific SMA cable assembly: a right-angle male connector on one end, a straight female on the other, joined by RG316 coaxial cable. It is placed in the section comparing different cable families, alongside a similar assembly with RG58. The image helps engineers visually distinguish between assemblies that use different coax types behind the same SMA connectors. The surrounding text emphasizes that two assemblies both labeled "SMA cable" can perform completely differently—one may work at 1 GHz but fail at 5 GHz, while the other survives comfortably. The connector didn't change; the coax did.

This figure shows an SMA male to SMA male cable assembly constructed with RG58 coaxial cable. It serves as a direct visual comparison to Figure 4's RG316-based assembly. The surrounding text explains that RG58 solves a different problem—it offers lower loss but at the cost of increased bulk and reduced flexibility. In dense hardware, RG58 is often excluded before RF is even considered. The image helps engineers visualize the trade-off between loss and mechanical flexibility when choosing between different coax families for their SMA-terminated assemblies.

A lot of confusion starts with names.

Engineers talk about “SMA cable” as if it were a cable type. It isn’t. It’s a connector choice. What really defines performance is the coax sitting behind that connector. That might be rg316 cable, RG58, or a heavier low-loss line. All are nominally 50 ohms. They behave very differently once frequency and length creep up.

This is why two assemblies that both say “SMA cable” on the bag can perform nothing alike on the bench. One may look fine at 1 GHz and fall apart at 5 GHz. The other survives comfortably. The connector didn’t change. The coax did.

If you want a deeper reference point for what SMA itself guarantees—and what it doesn’t—the overview on Wikipedia’s SMA connector page is a useful baseline. It makes clear that SMA defines an interface, not cable performance.

Balance loss, diameter, and bend radius for compact RF hardware

Compact hardware forces trade-offs that spreadsheets don’t always show.

Thin coax routes easily. It slips past shielding cans. It bends where thicker cable simply won’t. That convenience is real, and in dense designs it often decides the outcome. But thin coax pays for that flexibility with loss.

There’s no universal rule here. Some designs can afford a few extra dB and gain mechanical simplicity. Others can’t. What matters is being honest about which side of that line your system sits on, instead of assuming all 50-ohm cable behaves “close enough.”

Use mmcx cable where board-level density matters more than connector torque

Threaded connectors are robust, but they consume space. In small RF modules, that space simply isn’t available. That’s where mmcx cable earns its place.

MMCX connectors trade torque strength for density. They are excellent inside enclosures where cables are short, supported, and rarely mated. They are a poor choice where users will twist, pull, or repeatedly reconnect them.

Many practical designs split the difference: MMCX at the module, SMA at the enclosure wall. The internal run stays compact. The external interface stays rugged. When this boundary is chosen deliberately, it works very well.

Decode product names: “sma coax cable”, “sma rf cable”, “rg316 coax cable”

Product listings are rarely precise.

“SMA coax cable” and “SMA RF cable” are usually marketing variants for the same thing: a coaxial assembly terminated with SMA connectors. The phrase tells you almost nothing about loss, shielding, or usable frequency.

“RG316 coaxial cable” is more meaningful because it names the coax family. Even then, quality varies widely depending on construction and termination.

When performance matters, the only reliable path is to ignore the headline name and look for measurable data: attenuation per meter, frequency sweep results, and connector construction details.

Choose SMA cable specs for frequency, power, and length

Set operating band and VSWR targets for sma rf cable runs

Frequency sets the tone for everything else.

A cable that behaves politely below 1 GHz can become unpredictable above 3 GHz. Loss rises. Return loss worsens. Small mechanical imperfections suddenly matter. This is where vague specifications stop being helpful.

Before selecting an sma rf cable, it helps to write down two simple targets:

How much loss can I tolerate?

How much return loss do I need to preserve?

Those numbers don’t need to be aggressive. They just need to exist. Without them, cable choice turns into a guess dressed up as experience.

Pick impedance, shielding, and jacket for your environment

Impedance is easy: 50 ohms, always.

Shielding and jacket choice are not. A bench jumper wants flexibility and low handling noise. An outdoor antenna cable wants UV resistance and moisture tolerance. An internal harness may care more about temperature rating than anything else.

Trying to satisfy all of those with a single SMA cable usually leads to quiet failures later—cracked jackets, unstable measurements, or corrosion you didn’t plan for.

Decide when rg316 coaxial cable is acceptable—and when it isn’t

RG316 coaxial cable is extremely forgiving mechanically. That’s why it shows up everywhere. Electrically, it’s less forgiving once length or frequency increases.

For short internal runs, RG316 is often the right answer. For long antenna feeds or higher-power links, it becomes a liability. The moment your margin starts to feel “tight,” RG316 is usually the first place to look.

If you want a more detailed breakdown of where RG316 fits and where it doesn’t, the discussion in RG316 Coaxial Cable Specs, Loss & Uses goes deeper into measured behavior.

Use a sma cable planning matrix to keep loss visible

Many RF problems survive because nobody ever writes the numbers down.

A simple planning matrix forces the issue. It doesn’t need to be fancy. It just needs to make loss and margin explicit.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| f_GHz | Operating frequency |

| P_out_dBm | Source or transmit power |

| L_m | Planned cable length |

| Cable_family | RG316, RG58, LMR-200, etc. |

| α_dB_per_m | Loss per meter at frequency |

| Conn_pairs | Connector or adapter pairs |

| Loss_conn_dB | Typical loss per pair |

| Total_path_loss_dB | Cable + connector loss |

| Margin_available_dB | Remaining link margin |

| Flag_ok | PASS if margin ≥ 6 dB |

Control loss and VSWR in SMA RF cable runs

Keep bend radius reasonable—especially near connectors

Most cable damage doesn’t happen in the middle of the run. It happens near the connector. Tight bends distort the dielectric and introduce local impedance changes that show up as return-loss ripple.

This is one of those issues that feels theoretical until you measure it. Then it becomes obvious.

Limit adapter stacks between mmcx connector and sma connector

Adapters solve problems quickly. They also hide them well.

One adapter is usually fine. Two may still behave. Three or four chained together often explain mysterious loss and poor repeatability. When possible, replace adapter stacks with a single pigtail or directly terminated assembly.

Measure long sma rf cable assemblies instead of assuming

If a cable matters, measure it.

A quick VNA sweep tells you more than any catalog description. Comparing a suspect cable against a known-good reference is often enough to identify damage, aging, or manufacturing variation.

Retire lab sma cable before it becomes a variable

Lab cables don’t fail loudly. They drift. Threads loosen. Center pins wear. The result is a cable that still passes signal but no longer behaves consistently.

If touching a cable changes your measurement, the cable has already overstayed its welcome.

Integrate SMA cable with MMCX connectors and adapters

Decide where mmcx connector and sma connector belong—on purpose

A common, reliable pattern is MMCX at the module and SMA at the enclosure boundary. It keeps boards small and external interfaces durable.

Problems arise when this boundary is accidental rather than designed. Then strain relief, grounding, and repeatability suffer.

Use mmcx to sma adapter assemblies sparingly

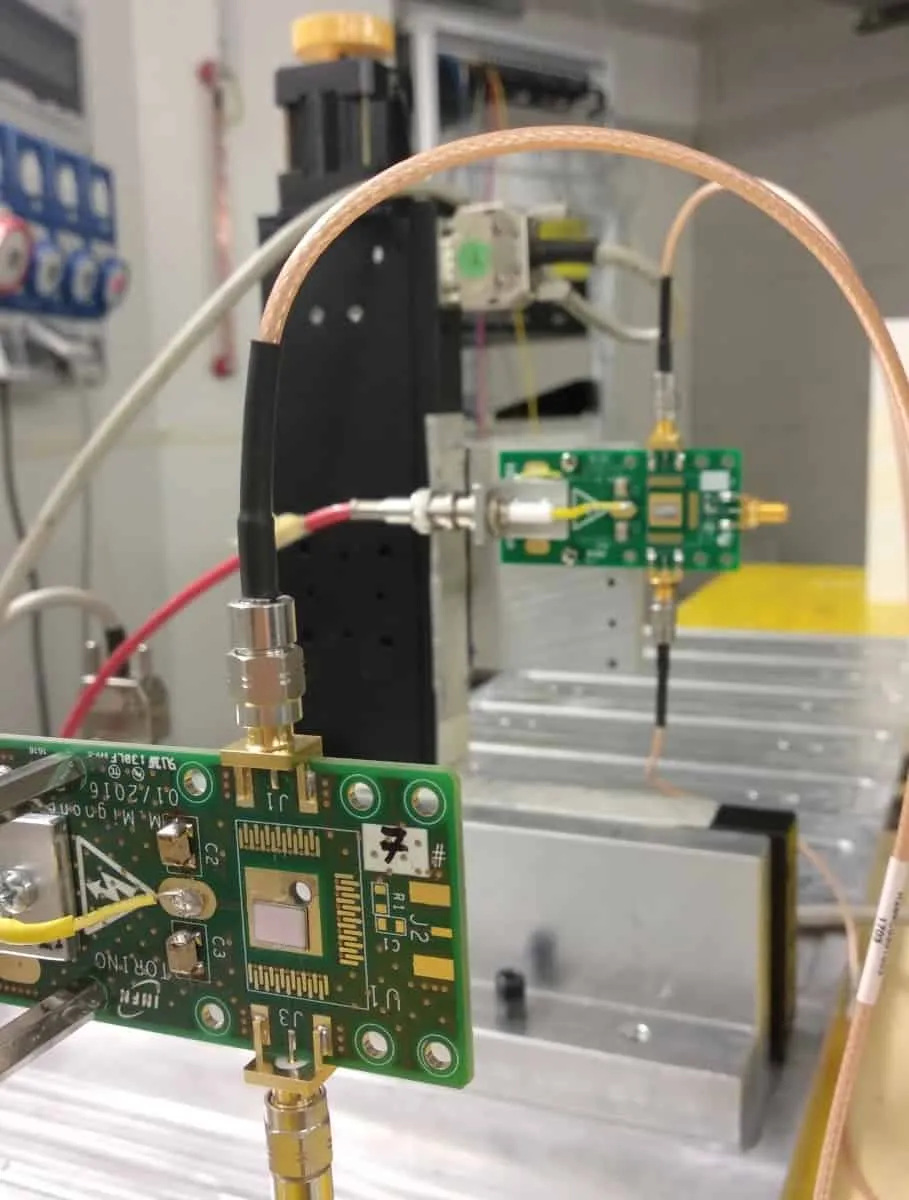

This figure depicts a rigid MMCX to SMA adapter. It appears in the section discussing how to integrate SMA cable with MMCX connectors and adapters. The surrounding text advises that rigid adapters stacked together invite both electrical and mechanical trouble. A single MMCX to SMA adapter or a short pigtail usually performs better and survives vibration more gracefully than multiple stacked adapters. The image visually reinforces this guidance, showing the type of component that should be used deliberately and sparingly in critical RF paths.

Route mmcx cable internally, then hand off to external sma cable

Verify 50-ohm continuity across every transition

Every connector, adapter, and jumper must maintain impedance. One weak link dominates return loss for the entire chain.

If you need a general impedance reference refresher, the background section of Wikipedia’s coaxial cable article is useful—not for specs, but for grounding the concepts.

Plan SMA cable for antennas, test setups, and field deployments

Size sma antenna cable for rooftop, vehicle, and gateway installations

Once an SMA cable leaves the bench and goes into the field, the rules change. Length becomes real length, not “about this long.” Temperature swings are no longer theoretical. Vibration is continuous, not occasional.

For rooftop and mast-mounted antennas, cable loss compounds quickly. A few extra meters routed “just to be safe” can erase link margin you assumed was there. In vehicle installations, flex and vibration matter more than absolute loss. A cable that looks electrically fine may fail mechanically long before it degrades RF performance.

This is why antenna cable planning should happen alongside enclosure and mounting design, not after it. Treat the SMA antenna cable as part of the mechanical system as much as the RF one. If you want a deeper antenna-focused discussion, the practices outlined in SMA Antenna Cable Best Practices align closely with what shows up in real deployments.

Design bench setups so sma cable does not dominate measurement uncertainty

On a test bench, cables should disappear into the background. If swapping a cable changes a result by more than expected, the setup is already compromised.

Short, known-good SMA jumpers are worth standardizing. Many labs keep one or two “reference” cables that are rarely moved and only used for verification. Everything else is compared against them. This simple habit catches problems early and keeps cable aging from creeping into data unnoticed.

Handle strain relief, grommets, and bulkhead feed-throughs around sma coax cable

Most SMA cable failures don’t happen in the middle of a run. They happen at transitions. Where the cable exits an enclosure. Where it bends sharply around a panel edge. Where vibration concentrates stress near the connector.

Strain relief, grommets, and properly mounted bulkheads are not accessories. They are life-extension tools. Ignoring them almost guarantees that a cable will become a maintenance item sooner than planned.

Document temporary vs permanent sma cable paths for technicians

Technicians treat cables differently depending on how they are labeled. A cable that looks temporary will be moved. A cable that looks permanent will be respected.

Clear documentation—sometimes as simple as a tag or drawing—prevents accidental changes during service or upgrades. This matters more than many teams expect, especially in shared or high-turnover environments.

Avoid common SMA cable mistakes in RF projects

Mixing 50-ohm sma cable with 75-ohm video coax in the same path

This mistake is common in mixed RF and video systems. Adapters make it physically possible. The system may even appear to work at first.

Electrically, it’s a compromise. Reflections increase. Return loss worsens. At higher frequencies or longer lengths, the impact becomes visible. Keeping RF and video paths clearly separated avoids a class of problems that are hard to debug later.

Over-using thin rg316 cable in long outdoor or high-power links

RG316 is convenient. That convenience is often mistaken for suitability.

In long outdoor runs or higher-power links, RG316’s attenuation and thermal limits become liabilities. These failures are rarely dramatic. They show up as reduced range, unstable links, or performance that degrades with temperature.

Reusing worn or poorly crimped assemblies in production tests

A bad cable in production testing is worse than no test at all. It creates noise in the data and erodes trust in results.

Production environments deserve dedicated, qualified SMA cable assemblies. Retired lab jumpers do not belong there, no matter how tempting it is to reuse them.

Confusing sma rf cable specs with marketing labels on patch leads

Low-cost patch leads often advertise impressive frequency ratings without meaningful test data. They may work adequately at low frequencies and short lengths, then fall apart quietly at the edges.

When performance matters, rely on measured specifications, not packaging claims.

Evaluate vendors and custom SMA cable assemblies

What to ask suppliers about test data, sweep frequency, and tolerances

A serious supplier can tell you how a cable was tested, over what frequency range, and with what tolerances. That information matters far more than brand names or plating descriptions.

If a supplier cannot answer basic questions about insertion loss or return loss measurement, that’s usually a signal—not a good one.

When to specify rg316 cable vs heavier low-loss coax in RFQs

RFQs should reflect reality, not convenience. Specify RG316 where flexibility and compact routing are required. Specify heavier, lower-loss coax where length, frequency, or power demand it.

Leaving cable choice vague invites substitutions that may meet the letter of the requirement but not the spirit.

Qualify mmcx cable and mmcx to sma adapter assemblies for vibration and shock

Standardize part numbers for sma cable across labs, production, and service

How are SMA cable assemblies evolving with 5G and IoT?

Higher-frequency sma cable requirements in 5G, Wi-Fi 6E, and small cells

As operating bands move upward, tolerances tighten. Phase stability, connector repeatability, and shielding quality matter more than they did at lower frequencies.

Assemblies that were “good enough” a decade ago often struggle quietly in modern systems. This isn’t because they got worse—it’s because requirements got stricter.

Growth of compact IoT modules using mmcx connector plus external sma cable pigtails

Compact IoT modules favor dense board layouts. MMCX connectors fit that reality. External antennas still demand SMA for durability and compatibility.

The result is a growing number of designs that rely on short MMCX pigtails handing off to external SMA cables. When executed well, this pattern balances density with field robustness.

RF coaxial cable assembly market trends—and why quality matters more now

Industry analyses consistently point to steady growth in RF coaxial cable assemblies through the early 2030s, driven by 5G infrastructure, aerospace systems, data centers, and IoT deployments. As volumes increase, quality variation becomes more visible.

In other words, cable quality matters more now not because cables are new, but because systems are less forgiving.

Answer practical questions about SMA cable selection (FAQ)

How long can an sma cable be at 2.4 GHz before loss becomes a problem?

Is rg316 coaxial cable a good choice for sma antenna cable outdoors?

Can I mix mmcx connector and sma cable in one RF link without hurting VSWR?

What is the difference between “sma cable”, “sma coax cable”, and “sma rf cable”?

How do I test whether an old sma cable assembly has gone bad?

When should I switch from rg316 cable to a thicker low-loss coax family?

Do I really need test-grade sma cable for my application?

Final takeaway

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.