SMA Cable Selection Guide for RF and Antenna Systems

Jan 9,2026

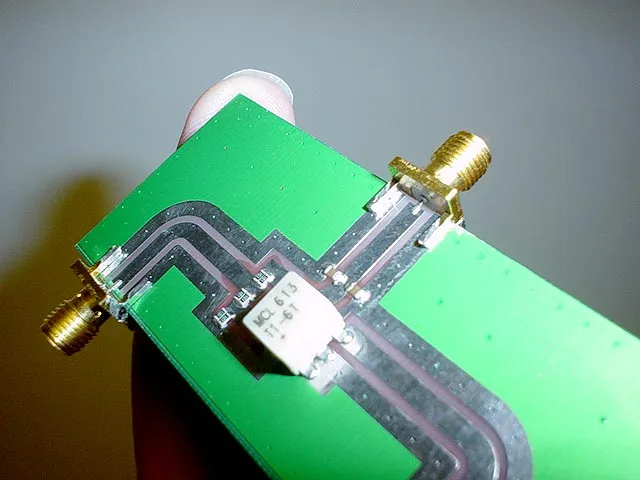

This diagram visually maps the critical yet often overlooked position of the SMA cable, connecting controlled environments (like PCBs) to uncertain external elements (like antennas and enclosures), highlighting its role as a boundary component.

In RF systems, failures rarely announce themselves clearly. The radio powers up. The antenna is connected. The link works—at least at first. Then range feels inconsistent. Higher data rates drop sooner than expected. Small changes in routing suddenly matter.

More often than not, the issue traces back to a sma cable that was treated as an afterthought.

An SMA cable sits at a deceptively quiet point in the signal chain. It is short. It is flexible. It usually gets added late, after the PCB, enclosure, and antenna already feel “done.” That timing is exactly why it deserves more attention, not less.

This guide focuses on how sma rf cable assemblies behave in real systems—where mechanical stress, connector pairing, and length planning matter just as much as datasheet loss numbers.

How does an SMA cable sit inside your RF signal chain?

Map SMA cable roles between PCBs, enclosures, antennas, and test gear

This graphic conceptualizes the SMA cable's function of transitioning signals from tightly managed PCB geometries to the variable conditions of the external world, such as vibration and temperature changes.

An sma cable is best understood as a boundary component. It marks the transition between controlled RF environments and everything outside them.

On one side, you have tightly managed structures: PCB microstrip, stripline, or module launch geometries. On the other side, you have uncertainty—enclosure tolerances, antenna placement, human handling, vibration, and temperature changes. The SMA cable bridges those two worlds.

In practical systems, sma rf cable assemblies most often serve three roles:

- PCB or RF module → enclosure wall

- Instrument or test port → device under test

- Panel bulkhead → external antenna or feeder transition

What matters here is not just signal transmission, but repeatability. A poorly chosen SMA cable can mask issues during early testing, only to become the weak link during compliance testing or field deployment.

This is why many RF engineers treat the SMA cable as part of the “external RF interface,” not just a passive jumper. If your project already includes an SMA connector strategy, it’s worth reviewing how that strategy connects to cable selection. A deeper connector-level discussion is covered in the SMA connector guide when dimensions and gender details need clarification.

Separate SMA RF cable from long feeder lines and tiny U.FL pigtails

This image shows a typical board-level interconnection cable, transitioning from a compact U.FL connector to a more robust SMA male connector, emphasizing its use for short, internal connections rather than external routing.

Not all coaxial cables that terminate in RF connectors serve the same purpose.

- U.FL / MHF / MCX pigtails are designed for board-level connections measured in centimeters. They prioritize compactness over durability.

- SMA cables typically operate in the 0.1–2 meter range, where flexibility and connector robustness matter.

- Long feeder cables such as RG58 or LMR-series lines prioritize low attenuation over distance and are rarely intended for repeated handling.

Confusing these categories is a common source of problems. Ultra-thin coax works well inside enclosures but fails quickly when routed through panels. Heavy feeder cable performs electrically but creates stress at small SMA connectors when used as a short jumper.

Field experience from production builds documented on tejte.com shows that many “mystery RF issues” disappear once each cable type is limited to its intended role.

Use SMA coax cable as the “last flexible segment” before bulkier coax

This photo depicts a common lab application where a short, flexible SMA cable is used to interface between a precision test instrument port and a passive component like an attenuator, absorbing mechanical mismatch.

A helpful way to frame sma coax cable selection is to think of it as the final flexible segment in the RF chain.

Typical architectures look like this:

- Test instrument SMA port → SMA cable → attenuator or load

- RF module → SMA cable → panel bulkhead → outdoor feeder → antenna

In both cases, the SMA cable absorbs mechanical tolerance and routing complexity so that stiffer coax does not stress connectors or PCB launches. That mechanical role is just as important as its electrical one.

When SMA cables are forced to act like feeder cables—too long, too stiff, or exposed to the environment—the system becomes fragile. Conversely, when feeder cables are used where an SMA jumper should be, connector fatigue and impedance irregularities often follow.

How should you select the coax type behind each SMA connector?

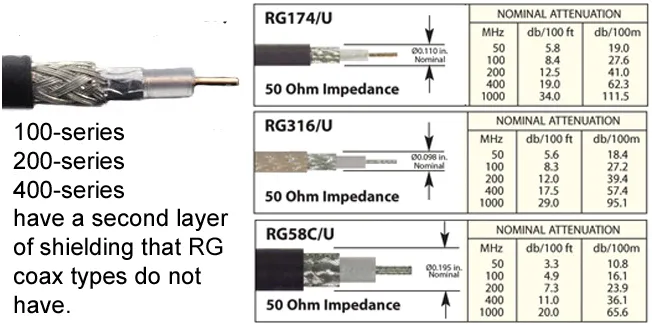

Compare RG316, RG174, 1.13, and RG58 for SMA coaxial cable builds

This chart provides a clear side-by-side comparison of key electrical and mechanical properties of popular coaxial cables, aiding engineers in selecting the appropriate type based on flexibility, loss, and durability needs for their SMA assemblies.

The coaxial cable hidden behind the SMA connector defines most of the assembly’s real-world behavior.

For sma coaxial cable builds, four families appear most often:

- 1.13 mm coax: extremely compact, very flexible, but high loss and limited durability

- RG174: lightweight and flexible, moderate loss, suitable for light-duty use

- RG316: PTFE dielectric, good thermal stability, balanced loss and flexibility

- RG58: thicker, lower loss per meter, mechanically stiff

Among these, RG316 has become the default for many engineers. It tolerates higher temperatures, survives repeated handling better than RG174, and avoids the extreme loss of ultra-thin coax. That balance explains why RG316-based sma rf cable assemblies dominate lab, router, and IoT device use.

RG58 still plays a role, but usually as a transition toward longer feeder lines rather than as a general-purpose SMA jumper.

Match coax families to indoor, outdoor, and in-box SMA cable runs

This infographic offers practical selection guidance, visually associating specific coaxial cable families (like RG316 or 1.13mm) with their ideal operational environments to ensure reliability and performance.

The same coax does not belong everywhere.

- Inside enclosures: 1.13 mm or RG316, depending on bend radius constraints

- Laboratory benches: RG316 or RG174 for durability and handling

- Outdoor transitions: short SMA cable → adapter → low-loss feeder

Choosing coax based purely on attenuation often leads to unnecessary stiffness or premature wear. Manufacturers and distributors consistently emphasize that environment and handling cycles should drive coax choice just as much as frequency.

For designs that mix multiple cable families, documenting those boundaries early helps avoid late-stage substitutions. If you are already planning mixed assemblies, the RF cable guide provides a broader view of how different coax families interact across an entire system.

Avoid mixing 50-ohm SMA cable with 75-ohm broadcast coax

This mistake still happens—usually because everything physically fits.

SMA connectors are designed for 50-ohm systems. Many broadcast and video coaxial cables are 75 ohms. Adapters make them mechanically compatible, but electrically mismatched.

Even short impedance discontinuities can increase return loss and introduce ripple, especially across wideband or higher-frequency systems. These effects often remain invisible at low data rates and only surface when margins tighten.

As a rule, if a system is built around sma cable assemblies, every coax segment in that path should remain 50 ohms unless a deliberate impedance transformation is part of the design.

What electrical specs actually matter on an SMA RF cable?

Set practical goals for loss and VSWR from DC to 6–7 GHz

In real systems, chasing the lowest possible loss is rarely productive. What matters is staying within predictable limits.

For most sma rf cable applications supporting Wi-Fi, LTE, GNSS, or sub-6 GHz 5G, engineers typically target:

- Total insertion loss that preserves link margin

- VSWR that remains stable across temperature and handling

- Repeatable performance from cable to cable

Short SMA cables rarely dominate loss budgets, but they do influence mismatch behavior. Poor connector transitions often contribute more to system degradation than the coax itself.

Rather than optimizing one parameter in isolation, experienced teams define acceptable ranges and validate consistency. That approach scales far better across production and testing.

Understand power handling and shielding needs for SMA RF cable

Although power handling is rarely the first limit in SMA cables, shielding quality often is.

Higher braid coverage reduces leakage and susceptibility, which becomes important in dense enclosures or multi-radio designs. , a slightly thicker sma coaxial cable with better shielding can outperform a thinner, lower-loss alternative.

Power, shielding, and mechanical durability interact. Ignoring any one of them usually shows up later as noise, instability, or unexplained drift.

How do you pick SMA cable end types and gender combinations?

Choosing the right coax is only half the job. In practice, many RF issues trace back to end-type pairing, not the cable body itself.

SMA connectors look deceptively symmetrical. Threads engage smoothly even when the pairing is wrong. That false sense of correctness is why connector gender errors often survive early testing and only surface later—when performance margins tighten.

Before selecting any sma cable, it helps to separate mechanical compatibility from electrical correctness.

For background on SMA connector structure and polarity, Wikipedia’s overview of the SMA connector provides a neutral reference point. What follows focuses on how those connectors behave once turned into real cable assemblies.

Use SMA male to SMA male cable for direct device-to-device and test links

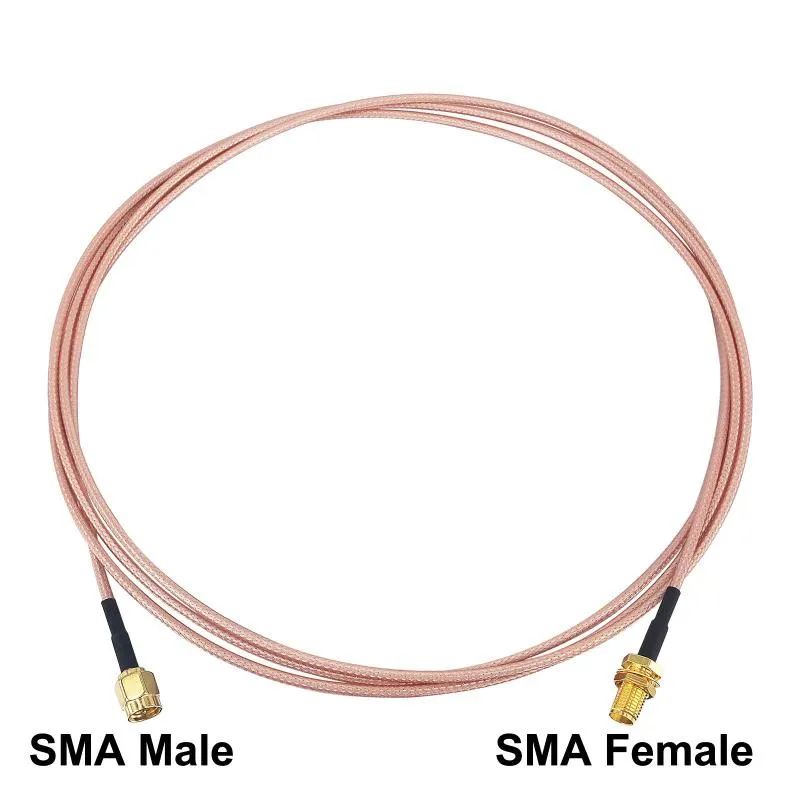

This image shows a standard SMA male-to-male test cable, which provides the most direct and reliable connection between two female ports, minimizing signal path discontinuities and adapter wear in lab or test scenarios.

The sma male to sma male cable is the cleanest solution when both endpoints present SMA female jacks.

Typical examples include:

- RF signal generator → DUT

- Spectrum analyzer → filter or attenuator

- Access point → RF load during validation

This configuration minimizes interface count. Every additional adapter introduces two more transitions: metal-to-metal contact, impedance discontinuity, and mechanical tolerance. At low frequencies, that rarely matters. Above a few gigahertz, it often does.

In lab environments where cables are frequently swapped, a direct sma male to sma male cable also reduces wear. Adapters tend to stay attached to instruments longer than cables do, accumulating mating cycles unevenly. Removing them from the chain simplifies maintenance.

For teams that regularly test different cable lengths or coax types, standardizing on a small set of M–M test cables often pays off faster than managing drawers full of adapters.

Use SMA male to SMA female cable for extensions and panel feed-throughs

This photo highlights an SMA male-to-female cable, essential for connecting a device port to a panel mount or for creating extensions. It acts as a mechanical decoupler, absorbing tolerances between components.

The sma male to sma female cable becomes essential once panels, bulkheads, or enclosure walls enter the picture.

Common scenarios include:

- Router SMA port → internal extension → panel bulkhead

- RF module → flexible jumper → enclosure wall

- Antenna relocation without PCB redesign

In these cases, the cable is no longer just a signal path—it is also a mechanical decoupler. It absorbs tolerance stack-up between PCB location, enclosure cutout, and external antenna orientation.

Stacking rigid adapters can work electrically, but mechanically it creates a lever arm that stresses the connector solder joints or bulkhead threads. Many enclosure-related failures traced in production systems disappear once those stacks are replaced with a short sma male to sma female cable.

If bulkhead selection is still open, it’s worth aligning cable end types with the bulkhead style early. A deeper discussion of panel transitions appears in the SMA bulkhead and extension guide.

Align SMA antenna cable builds with router, gateway, and module ports

This image focuses on an SMA cable designed for antenna connections, which must endure more rotation, torque, and environmental exposure than standard lab cables. It underscores the importance of specifying connector polarity (SMA vs. RP-SMA) explicitly.

An sma antenna cable is often treated as interchangeable with any other SMA jumper. Electrically, that is sometimes true. Mechanically and operationally, it often is not.

Antenna cables tend to see:

- More rotation and torque

- More environmental exposure

- More frequent reconnection

They also intersect with one of the most common sources of confusion in Wi-Fi and cellular products: SMA vs RP-SMA polarity. Many routers and gateways expose RP-SMA connectors by convention, while antennas and modules may use standard SMA.

A cable that “fits” mechanically can still invert polarity and silently degrade performance. This is why antenna-focused assemblies should be specified explicitly as sma antenna cable, with connector gender and polarity written out in full—not assumed.

If polarity conventions are still unclear in your system, the RP-SMA vs SMA identification guide provides a quick decision framework.

How should you plan SMA cable lengths, colors, and labels for real workflows?

This photograph demonstrates the value of standardizing cable lengths within an organization. Using a small set of defined lengths (like those shown) simplifies inventory management, procurement, and performance estimation for RF teams.

Cable problems are not always electrical. Many are logistical.

When multiple teams share lab benches, production lines, and field test kits, length chaos becomes a real risk. Engineers grab what’s nearby. Assemblies get repurposed. Over time, the system drifts away from its original intent.

Intentional planning around sma rf cable length, color, and labeling prevents that drift.

Define standard length tiers for SMA cable in labs and production

Most teams converge on a small set of practical lengths:

- 0.1 m

- 0.2–0.3 m

- 0.5 m

- 1.0 m

- 1.5 m

- 2.0 m

These tiers cover most routing scenarios without creating unnecessary SKUs. They also make loss estimation easier. When everyone knows that “0.5 m RG316” is the default, unexpected performance changes become easier to spot.

Custom lengths still exist—but they become exceptions, not the norm.

PTFE dielectric, braid coverage, and FEP sheath—how each layer fails in the field

RG316 reliability is layered. PTFE dielectric governs impedance stability. The braided shield provides RF containment and mechanical reinforcement. The FEP sheath protects against environment and abrasion. Field failures usually begin in one layer and propagate.

Excessive bending stresses the dielectric. Vibration fatigues the braid. Chemical exposure weakens the sheath. When these stressors overlap—tight bends near heat sources combined with vibration—degradation accelerates. Looking only at the headline temperature rating hides these interactions.

Use color sleeves and heat-shrink to distinguish cable roles

Color coding works because it reduces thinking under pressure.

Common patterns include:

- Black: antenna leads

- Blue: lab test cables

- Clear or brown: internal harnesses

The exact colors matter less than consistency. Once a convention is established, engineers can identify cable purpose at a glance—without reading labels or checking drawings.

Teams selling or sourcing cables through platforms like tejte.com often find that color options reduce mispicks just as effectively as part numbers.

Build label text that encodes band, length, and end types

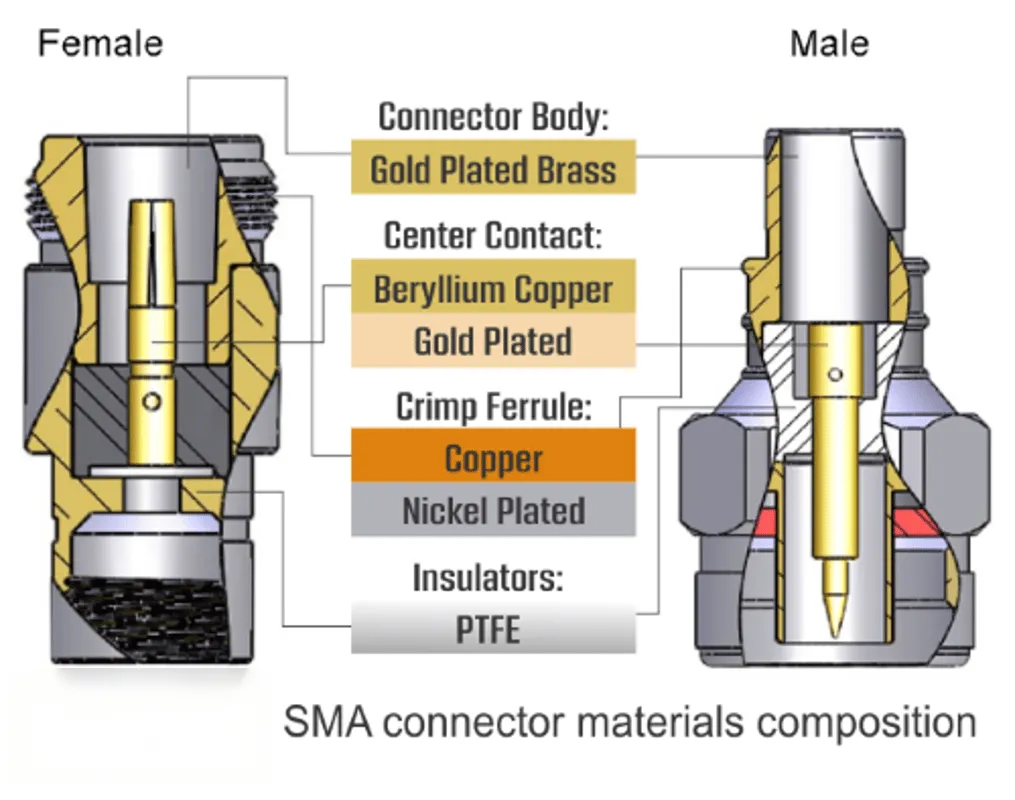

This technical diagram provides a detailed breakdown of the materials used in each part of a typical SMA connector (e.g., gold-plated brass body, beryllium copper center contact, PTFE insulator), which directly influences its electrical performance, durability, and cost.

Labels should answer the most common questions instantly:

- What band was this intended for?

- How long is it?

- What are the connector ends?

A practical example:

“2G4 SMA M–F 0.5 m RG316 – Router Antenna”

That single line prevents a surprising number of mistakes during assembly, test, and field support.

SMA Cable Ordering & Inventory Matrix

This matrix is designed to turn vague requirements into unambiguous specifications.

Inputs

| Field | Example |

|---|---|

| Application | Router antenna |

| Frequency band | 2.4 GHz |

| Estimated run length | 0.42 m |

| Coax type | RG316 |

| End A | SMA male |

| End B | SMA female |

| Usage type | sma antenna cable |

Derived logic

- Length tier:

- ≤0.15 m → 0.1 m

- 0.15–0.35 m → 0.3 m

- 0.35–0.75 m → 0.5 m

- 0.75–1.25 m → 1.0 m

- 1.25–1.75 m → 1.5 m

- 1.75 m → 2.0 m or custom

- SKU format:

SMA-[Coax]-[Band]-[Len]-[EndA][EndB]

Example: SMA-RG316-2G4-0P5-MF

- Estimated loss (simplified):

loss_dB ≈ loss_per_m(coax, band) × length_m-

Outputs

| Meaning | Output |

|---|---|

| Risk flag | OK / Check loss / Check bend radius |

| Notes | e.g., "panel sealing required", "indoor use only" |

How can you route and mount SMA antenna cables so they survive real deployments?

Routing is where otherwise “correct” sma cable choices quietly fail. Electrical specs may look fine on paper, but poor mechanical handling can shift impedance, fatigue connectors, or introduce intermittent faults that are almost impossible to reproduce on the bench.

Experienced teams treat routing and mounting as part of the RF design—not an afterthought delegated to final assembly.

Respect bend radius and strain relief rules for SMA coax cable

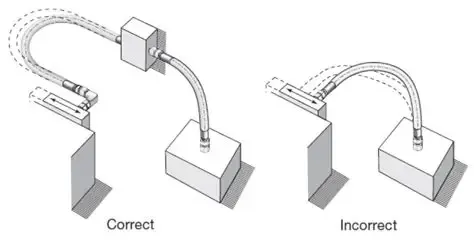

This instructional diagram contrasts proper and improper cable routing techniques. It emphasizes the critical need to maintain a generous bend radius (especially near connectors) and to use strain relief methods to prevent premature cable failure due to mechanical stress.

Every sma coax cable has a minimum bend radius, even if the datasheet does not highlight it prominently. A conservative field rule is no tighter than 10× the cable’s outer diameter, especially near the connector tail.

Violating this rule does not usually cause immediate failure. Instead, it leads to slow degradation:

- Micro-cracks in the dielectric

- Shield deformation that alters local impedance

- Increased sensitivity to vibration and temperature cycling

The most common mistake is forcing a sharp bend right at the SMA connector body to “make it fit.” That location sees the highest mechanical stress and the least tolerance for deformation.

A short strain-relief loop costs very little space and often doubles cable life.

Secure SMA antenna cable along panels, racks, and masts without crushing it

Cable ties are useful—and dangerous.

Over-tightening compresses the dielectric and shield, subtly changing impedance. At lower frequencies this may go unnoticed. At higher bands, especially above 5 GHz, it can show up as unexplained mismatch or drift.

Best practices include:

- Tie to the jacket, not the connector

- Use cushioned clamps near panels and racks

- Avoid tying cables at regular electrical intervals

When routing sma antenna cable outdoors or near vibration sources, spacing and restraint matter more than brute force. A cable that can move slightly often survives longer than one locked rigidly in place.

Plan outdoor transitions from SMA cable to thicker low-loss lines

SMA connectors and cables are rarely designed for long outdoor exposure. Their role outdoors is typically transitional.

A common and robust architecture looks like this:

- Device or enclosure → sma cable (short)

- Bulkhead or adapter → N-type or 4.3-10 connector

- Low-loss feeder → antenna

This approach limits environmental stress on the SMA interface while preserving flexibility inside the enclosure. For projects that involve mixed connector families, documenting the transition point early prevents last-minute substitutions that compromise sealing or performance.

For a broader view of feeder and outdoor coax considerations, the general coaxial cable overview on Wikipedia provides useful background context.

How are Wi-Fi 7, 5G, and IoT trends reshaping SMA cable choices?

Follow SMA RF cable growth in 5G and industrial IoT

Despite the emergence of newer RF connectors, sma rf cable assemblies continue to grow in demand. Market analyses published across 2024–2025 consistently point to SMA’s durability in:

- Sub-6 GHz 5G small cells

- Industrial IoT gateways

- Test and validation systems

The reason is not novelty, but familiarity. SMA remains well understood, widely supported, and mechanically forgiving compared to many high-density alternatives. As long as systems require flexible RF transitions, SMA cable assemblies remain relevant.

Note new FAKRA-to-SMA cable assemblies in automotive and industrial IoT

Automotive and industrial platforms increasingly bridge legacy ecosystems with modern RF modules. One visible result is the rise of hybrid cable assemblies—such as FAKRA-to-SMA—that allow existing infrastructure to interface with newer radios.

These hybrids reinforce an important point: SMA is no longer just a lab or Wi-Fi connector. It is part of a larger interconnect ecosystem that spans automotive, industrial, and test environments.

Teams that standardize their sma cable specifications early find it easier to integrate these hybrids without redesigning core RF paths.

Watch Wi-Fi 7 external antennas driving SMA antenna cable demand

Wi-Fi 7 platforms have pushed more designs toward external antennas to maintain MIMO performance and thermal margins. That trend increases reliance on consistent sma antenna cable quality.

As data rates rise, tolerance for variation shrinks. Length, shielding, and connector integrity that once felt “good enough” now show measurable impact. This is one reason many vendors are revisiting their SMA cable standards rather than treating them as generic accessories.

How do you turn SMA cable decisions into a clean spec and purchasing flow?

Capture all SMA cable parameters in one engineering spec sheet

A complete SMA cable spec usually fits on a single page:

- Frequency range

- Maximum acceptable loss and VSWR

- Coax type

- Length tier

- Connector gender and polarity

- Environmental limits

What matters is not the format, but completeness. Partial specs invite assumptions—and assumptions are where mistakes begin.

If connector styles or dimensions are still unclear, linking that spec back to a central reference such as the SMA connector guide keeps teams aligned.

Translate technical needs into PO language factories understand

Factories and distributors do not see intent. They see text.

Clear purchase descriptions reduce silent substitutions. For example:

SMA M–F, RG316, 0.5 m, 50 Ω, indoor antenna cable, black sleeve, labeled

That line communicates more than a drawing reference alone ever will. It also makes audits easier months later when parts need to be reordered.

Standardize SMA RF cable families across product lines

The most scalable approach is to define families of sma rf cable assemblies shared across products:

- One family for lab and validation

- One for internal harnesses

- One for antenna connections

Once those families are validated, they become building blocks. TEJTE’s own catalog organization on tejte.com reflects this philosophy, grouping cables by role rather than by one-off configurations.

What SMA cable questions should your team settle before sign-off?

Align engineering, test, and operations on shared SMA cable families

If engineering prototypes use one cable and production uses another, document why. If test benches require tighter specs than shipped products, make that distinction explicit.

Misalignment here rarely causes immediate failure—but it often causes long debugging sessions later.

Identify high-risk links where SMA RF cable deserves extra attention

Certain links consistently justify extra scrutiny:

- High-frequency paths

- High-power transmit chains

- Outdoor or mobile installations

- Interfaces with frequent mating cycles

In these cases, cable choice is not just about cost or availability. It is about long-term stability.

FAQ — Practical SMA Cable Questions

Is an SMA antenna cable just a regular SMA RF cable with a different label?

Electrically, often similar. Mechanically and environmentally, antenna cables usually face higher stress and benefit from stricter selection.

How long can an SMA cable run be before loss becomes unacceptable at 5 GHz and above?

With common RG316 assemblies, many teams aim to stay under one meter. Beyond that, reassessing architecture or coax choice is wise.

Do I really need low-PIM SMA RF cable for indoor systems?

Only in multi-carrier or higher-power environments. For most indoor and development systems, standard assemblies are sufficient.

What is the simplest way to document SMA cable assemblies so suppliers don’t make mistakes?

Combine connector gender, coax type, length tier, frequency intent, and usage role in one clear line—supported by a standard matrix.

Can one 50-ohm SMA cable safely cover DC to 6 GHz for every project?

Electrically, often yes. Practically, mechanical and environmental differences mean not every project should rely on the same cable.

Final note

A well-chosen sma cable rarely draws attention. That is exactly the point.

When cable selection, routing, and documentation are handled deliberately, RF systems become easier to validate, easier to scale, and far easier to support.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.