SMA Bulkhead Cutout, Thread Length & Sealing Guide

Jan 6,2026

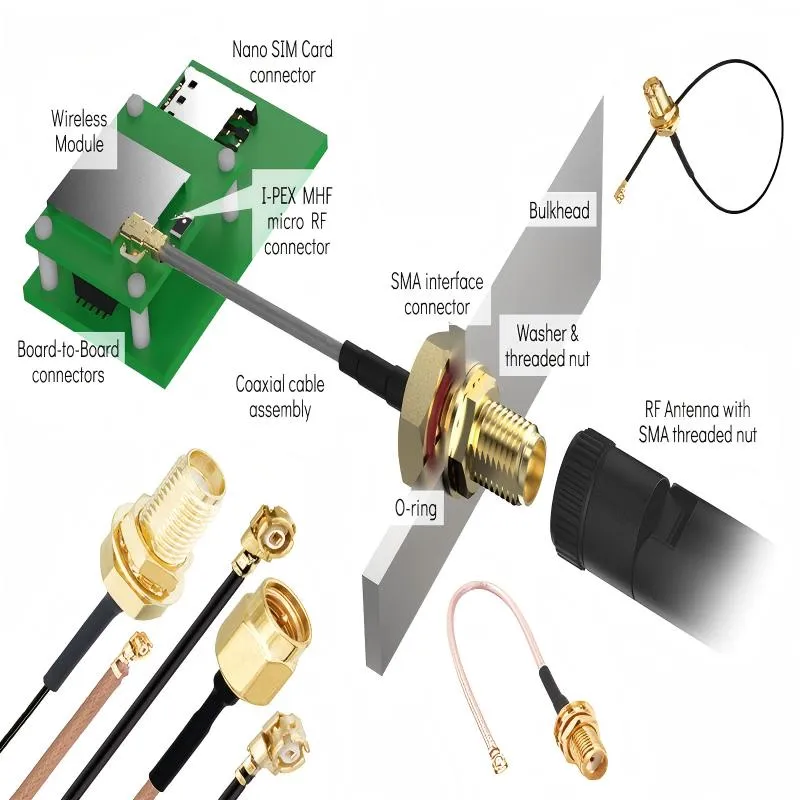

This exploded view diagram visually lists the complete connection chain from inside the device (wireless module, connectors) to the outside (antenna), including the SMA interface connector, coaxial cable assembly, O-ring, washer, threaded nut, and RF antenna with SMA threaded nut. It is used at the beginning of the article to establish a visual understanding of the overall SMA structure, emphasizing that it consists of multiple precision components, and neglect of any one link can lead to problems.

An SMA bulkhead connector almost never looks like a failure point during design review. It’s small, passive, familiar, and usually selected after the enclosure shape and antenna choice already feel “locked.” That’s exactly why it causes trouble later. In real products, bulkhead issues rarely announce themselves with dramatic failures. Instead, they show up as small, expensive annoyances: a connector that slowly loosens, a seal that passes lab testing but leaks after a season outdoors, or a radio link that looks fine on paper yet behaves unpredictably in the field. None of these problems come from advanced RF theory. They come from mechanical assumptions that were never written down.

This guide focuses on the practical mechanics of SMA bulkhead installation: how to size the panel hole correctly, how to choose thread length without guessing, and how to compress an O-ring enough to seal without destroying it. The intent is not to repeat datasheets, but to make the installation predictable the first time.

How do I size the panel hole and pick the right thread length without rework?

Measuring metal vs plastic vs stacked panels

With metal panels, measure the effective structural thickness. Surface finishes rarely add strength, but they do affect friction and how easily the connector rotates during tightening. Thin aluminum panels, especially those at or below 1.5 mm, are far less forgiving than they look once torque is applied.

Plastic enclosures behave differently. ABS and PC flex under load and creep over time. A plastic wall that measures 2.0 mm on a caliper may behave like something closer to 1.6 or 1.7 mm after compression. This is why plastic housings often need more thread engagement than their metal counterparts, even when the nominal thickness is the same.

For stacked panels—an outer shell with an inner bracket or reinforcement—the key is identifying where the O-ring actually seals. If the O-ring sits against the outer shell, only that layer defines the sealing thickness. The inner layer contributes to mechanical engagement, not waterproofing. Treating both as one continuous thickness is a common source of miscalculation.

A practical rule that holds up well in production is this: if the enclosure is plastic or composite, plan for an additional 0.5–1.0 mm of thread allowance compared with an equivalent metal panel.

Anti-rotation: round hole, keyed hole, or flange?

A single-nut SMA bulkhead relies on friction to resist rotation. That friction comes from the nut, the washer stack, and the panel surface. In low-vibration indoor equipment, this is often sufficient. Problems start when antennas are installed, adjusted, or replaced by hand. Every twist of the antenna transfers torque directly into the bulkhead body.

There are three common ways to manage this. Keyed or D-cut holes prevent rotation but complicate machining and tolerance control. Anti-rotation washers help, but only if the panel material is hard enough to resist wear. Flanged bulkheads move the load elsewhere entirely, transferring torque into the shear strength of mounting screws rather than relying on surface friction.

If the antenna will be handled frequently, or if the enclosure material is soft, moving to a 2-hole or 4-hole flange is less about overengineering and more about long-term stability.

How do I calculate thread engagement that’s secure but not over-compressed?

Bulkhead Thread Length Calculator

Instead of relying on visual judgment, use a simple additive model that reflects how the stack actually assembles:

L_required = t_panel + t_washer + t_gasket + h_nut + a_allow

Here, t_panel is the effective panel thickness, t_washer is the combined thickness of any flat or spring washers, t_gasket is the O-ring thickness after compression, h_nut is the usable thread height of the nut, and a_allow is an assembly allowance, typically 0.5–1.0 mm.

The output tells you two things immediately: whether a short, standard, or long bulkhead thread is appropriate, and whether you are approaching the point where a flanged connector would be mechanically safer. On production lines, one pattern repeats itself consistently: when the calculated value falls between two thread options, choosing the longer thread and tuning with washers almost always works. Choosing the shorter thread almost always leads to rework.

How do I achieve IP67 outdoors—what O-ring compression and torque should I target?

O-ring compression window and failure symptoms

For the elastomer O-rings commonly used in SMA bulkheads, an effective compression range of roughly 20–30% is a reliable target. Below that range, seals may pass initial tests but fail after temperature cycling or pressure changes. Above it, the rubber ages faster, rebound decreases, and long-term sealing performance degrades.

Over-tightening does not improve sealing. It shortens its lifespan. Under-compression often shows up as leaks after thermal cycling, while over-compression leads to flattened or cracked O-rings months later.

Tightening order and anti-loosening methods

Control matters more than brute force. A stable tightening sequence starts with hand-tightening until the O-ring first contacts the panel, followed by gradual torque application with a low-range wrench. After a short pause, a re-check confirms that the stack has settled.

Anti-loosening strategies depend on the environment. Light vibration can be handled with spring washers. Outdoor temperature swings often justify a medium-strength threadlocker. High-vibration environments usually push the design toward double nuts or flanged bulkheads. Torque alone does not prevent loosening; load distribution does.

When should I abandon a single-nut bulkhead and move to 2/4-hole flanges?

Vibration, shock, and backside reinforcement

This schematic explains, by comparing two structures, why flanged (2-hole or 4-hole) SMA interfaces are more reliable than single-nut types in environments with vibration, repeated handling, or soft material (e.g., plastic) enclosures. It visualizes how the single-nut design concentrates torque at one point (relying on friction), while the flange design evenly distributes the load through multiple screws, providing better long-term mechanical stability.

Flange screw selection, torque, and gasket stacking

Why does a connector that “fits” still fail? SMA vs RP-SMA in real ports

The 10-second identification rule: thread × pin or socket

This chart is a key tool for avoiding interface mismatch. It clearly shows the appearance characteristics of four connectors (SMA Male, SMA Female, RP-SMA Male, RP-SMA Female), focusing on two decisive attributes: thread type (external or internal) and center contact type (pin or socket). The article emphasizes that relying solely on labels or “looks like it fits” is insufficient to ensure correct electrical connection; matching must be based on this visual rule.

What mismatch looks like in the field

How do I choose extension length and reduce adapters on the outside run?

Once the bulkhead itself is mounted correctly, the next weak link is almost always the external run. Extension cables and adapters look harmless, especially when they’re short. At 2.4 GHz, that assumption often holds. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, it stops being true very quickly.

The core issue isn’t just insertion loss. It’s how loss, mismatch, and connector stacking interact. A short extension with one extra adapter can behave worse than a slightly longer cable with a direct connection. This is why extension planning needs to be intentional, not reactive.

5/6 GHz length tiers and the “shorter chain, higher margin” rule

This is typically a banded or stepped chart dividing extension cable lengths into key performance intervals (e.g., <0.3m, 0.3-0.5m, >0.5m). It visually illustrates that in high-frequency Wi-Fi applications, cable length does not have a linear impact but exhibits distinct performance “breakpoints.” As length increases, the erosion of link margin by loss and reflection intensifies, especially when combined with connector mismatch. It supports the article’s core argument that “shorter chains behave better than optimized chains with extra interfaces.”

At higher Wi-Fi bands, think in tiers rather than absolutes. For typical SMA antenna cables using common low-loss coax, several practical breakpoints show up consistently in testing.

Runs under roughly 0.3 m usually behave well enough to be ignored in system-level budgets. Between 0.3 m and 0.5 m, loss starts to eat into link margin, especially when combined with connector mismatch. Beyond 0.5 m, every additional connector and adapter needs to be accounted for explicitly. At that point, treating the extension as “just a cable” is no longer accurate.

A useful mental model is this: every time you add length or an interface, you’re spending margin. If the system has margin to spare, that’s fine. If it doesn’t, the first symptoms will appear at the highest data rates, not as a total link drop. This is why engineers often see devices that connect reliably at close range but fall apart under load or distance.

This schematic likely uses diagrams of chains from simple to complex, e.g., from a direct “device-antenna” connection to a multi-interface chain like “device-adapter-cable-antenna”. It visually conveys the article’s core idea: in high-frequency systems, reducing the number of interfaces (even if it means using a slightly longer single cable) often preserves performance better than using a shorter but more complex chain with multiple adapters. Performance degradation first manifests as reduced throughput at high data rates, not as a complete link drop.

Adapter penalties and when direct runs become mandatory

Adapters introduce two penalties at once. The first is insertion loss, which is usually small but cumulative. The second is reflection, which can be far more disruptive than the raw loss figure suggests. At 5/6 GHz, even modest return loss degradation can push a system out of its comfortable operating zone.

There are cases where adapters are unavoidable, such as transitioning between SMA and RP-SMA or accommodating legacy hardware. When that happens, the goal should be to keep the chain as short and as simple as possible. One adapter plus one cable is usually manageable. Two adapters plus a cable often isn’t.

In marginal systems—outdoor access points, directional antennas, compact gateways with limited RF headroom—direct runs matter. Replacing an adapter stack with a single correctly terminated cable often recovers more performance than switching to a thicker or lower-loss coax with extra interfaces.

Why does an RP-SMA antenna “work” on an SMA jack but still perform poorly?

This question keeps appearing because the failure mode is subtle. Mechanically, many SMA and RP-SMA combinations appear to mate. Electrically, they don’t.

The underlying issue is the center contact. SMA and RP-SMA intentionally invert the pin and socket arrangement. When mismatched, the connection may rely on incidental contact pressure rather than a designed interface. Sometimes it passes DC continuity checks. Sometimes it even radiates. Over time or under vibration, performance degrades.

The practical result is confusing behavior. RSSI readings may look acceptable at idle, but throughput collapses under load. Higher modulation schemes fail first. The system appears unstable rather than broken. This is why correct identification at the bulkhead matters just as much as correct sealing.

If you need a fast, repeatable way to identify ports before committing to cable assemblies or antennas, the field method outlined in RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Match & Ordering Guide avoids most of the common traps.

How do I document extension and bulkhead details so purchasing doesn’t bounce the order?

Bulkhead Ordering Checklist

A purchase order that clears on the first pass usually includes the following fields, explicitly written rather than implied:

Connector type (SMA or RP-SMA), center contact (pin or socket), cable type if applicable (for example, RG178), cable length, bulkhead or flange style with hole count, thread length option (short, standard, or long), panel thickness and hole diameter, waterproof cap requirement, and quantity.

The value of this checklist isn’t the list itself. It’s that it forces alignment between mechanical, RF, and procurement expectations. When these details are omitted, suppliers are forced to guess. When they’re written clearly, mistakes drop dramatically.

A simple practice that works well is to include a single consolidated note in the PO that combines interface, thread, sealing, and length in one line. That makes it difficult for any single detail to be misinterpreted downstream.

When does a single-nut bulkhead stop making sense from a system perspective?

The decision to move from a single-nut bulkhead to a flanged design is rarely about immediate failure. It’s about long-term behavior under real use.

Systems that live indoors, see little vibration, and rarely have antennas touched can often run single-nut bulkheads for years without trouble. The moment any of those conditions change, the margin shrinks.

Outdoor deployments, vehicle-mounted equipment, compact gateways with lightweight housings, and devices that are serviced in the field all apply repeated mechanical stress to the bulkhead. In those cases, the flange isn’t a luxury. It’s how you move stress away from friction interfaces that were never meant to carry it indefinitely.

What trends are tightening tolerances on bulkhead sealing and thread length?

Several recent deployment trends have quietly raised the bar for bulkhead design. Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 7 push more data through higher-order modulation, leaving less margin for mismatch and loss. The expansion of 6 GHz into outdoor and semi-outdoor environments increases exposure to temperature swings and moisture. At the same time, enclosures are getting thinner and lighter, often switching from metal to plastic or hybrid structures.

All of this compresses the acceptable tolerance window. A thread length that “usually works” becomes unreliable. An O-ring that was forgiving at lower frequencies starts to matter. Bulkhead installation moves from a mechanical afterthought to a system-level consideration.

This is also why bulkhead decisions increasingly sit alongside broader cable and loss planning rather than being treated as isolated hardware choices, something that ties naturally into system-level guides like the RG cable overview used as a hub reference in many designs.

What actually needs to be written on the PO so nothing gets held up or shipped wrong?

Most bulkhead delays don’t come from bad parts. They come from missing information. Somewhere between engineering and shipping, assumptions get made—and those assumptions are rarely the same on both sides.

“SMA bulkhead” by itself is not a specification. It’s a category. The moment a buyer, a warehouse clerk, or a contract manufacturer has to guess, you’ve already lost control of the outcome.

Why plastic enclosures change the rules more than most people expect

Plastic housings aren’t the problem. Treating them like thin metal is.

Under constant load, plastic relaxes. Under temperature cycling, it moves. Neither of those effects show up during initial assembly. They show up months later, when a connector that once felt solid starts to lose preload.

This is where many “mystery” field failures begin. The bulkhead itself hasn’t changed. The enclosure around it has.

Backing plates are one of the simplest ways to slow this process down. By spreading load over a larger area, they reduce localized deformation and help the joint hold its shape over time. Thread inserts can help with repeated assembly, but they don’t replace load distribution. If the enclosure is thin or lightweight, a flange often does more for long-term stability than increasing torque ever could.

Thread engagement margin also matters more with plastics. A design that barely meets engagement requirements on day one may fall below them once the material relaxes. Planning extra engagement from the start costs almost nothing and avoids chasing intermittent mechanical issues later.

At what point does sealing stop being “just mechanical” and start affecting RF behavior?

Water ingress is rarely binary. Most of the time, it’s gradual. Moisture finds its way in, sits where it shouldn’t, and slowly changes the electrical environment.

That’s why sealing should be viewed as part of the RF system, not just enclosure hygiene. Small changes in impedance around a bulkhead can increase reflections. Corrosion at the interface can raise contact resistance. None of this shows up as a clean failure. It shows up as degraded margins.

As operating frequencies climb and modulation schemes become more demanding, those margins shrink. A connector that still passes continuity checks may no longer support stable throughput. When engineers describe these problems as “RF instability,” the root cause is often mechanical drift that started at the bulkhead.

How do bulkhead choice, extension length, and connector type need to line up?

Reliable systems treat the bulkhead, the extension cable, and the antenna interface as one chain. Decisions made in isolation rarely hold up once the system is assembled.

The first step is always correct interface identification at the device port. Getting SMA versus RP-SMA wrong poisons everything downstream, even if the parts appear to fit. Once the interface is confirmed, the bulkhead style and thread length should match the enclosure material and how the antenna will be handled in real use, not just during assembly.

Extension length then becomes a margin decision. If the system has headroom, short extensions may be acceptable. If it doesn’t, reducing interfaces often helps more than upgrading cable type. These trade-offs are easier to manage when bulkhead decisions are made alongside overall cable planning rather than treated as a last-minute mechanical detail, which is why many teams reference broader hub material such as an RG cable overview when locking down final layouts.

Why recent deployments leave less room for “close enough” bulkhead installs

Several trends are tightening tolerances at the same time. Wi-Fi 6 and Wi-Fi 7 rely on higher-order modulation that is less forgiving of mismatch. The push into 6 GHz brings harsher environmental exposure. Enclosures continue to get thinner and lighter, often shifting toward plastics for cost and weight reasons.

Each of these trends reduces slack in the system. Practices that once worked by accident now sit right at the edge. Thread lengths that were “usually fine” need to be calculated. O-ring compression that was once forgiving needs to be controlled. Bulkhead installation stops being a background task and starts becoming part of system reliability.

Closing perspective: why SMA bulkheads fail quietly—and how to keep them boring

SMA bulkheads rarely fail in dramatic ways. They don’t burn out. They don’t snap in half. They just drift out of tolerance, one small assumption at a time.

The designs that hold up are not the ones with the most exotic hardware. They’re the ones where measurement, calculation, sealing, and documentation are all aligned. When panel thickness is measured correctly, thread engagement is calculated instead of guessed, O-rings are compressed intentionally, and purchase orders describe real installation conditions, bulkheads stop being a source of uncertainty.

That’s when they become what they were meant to be: boring, invisible, and reliable.

Frequently Asked Questions (SMA Bulkhead Installation)

How large should the panel hole be for an SMA bulkhead?

Is anti-rotation really necessary, or is it optional?

How much thread engagement is “enough” on a thin aluminum panel?

When does it make sense to move away from a single-nut bulkhead?

How tight should I compress the O-ring for outdoor sealing?

Can I safely run a half-meter extension cable at 6 GHz?

Why does an RP-SMA antenna sometimes seem to work on an SMA port?

What information should always be written on the purchase order?

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.