SMA Antenna Cable Selection for Real Deployments

Jan 6,2025

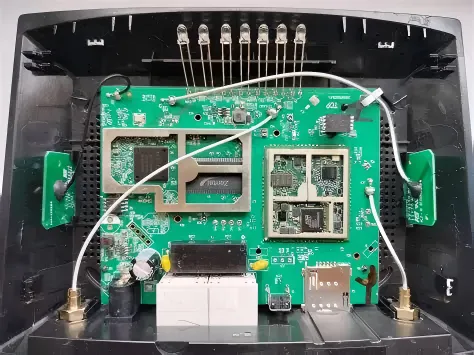

This is typically a simple diagram of an SMA cable or connector, placed below the article title. It aims to visualize the core component - the “SMA antenna cable” - emphasizing that although it appears passive and inexpensive, it has a decisive impact on link performance, EIRP compliance, and mechanical reliability in real deployments (especially in Wi-Fi, Sub-6 GHz products), setting the stage for the detailed discussion that follows.

An sma antenna cable rarely feels like a critical design decision.

It is passive. It is inexpensive. And in many projects, it gets chosen after the antenna, the radio module, and even the enclosure are already locked.

That timing is exactly why it causes trouble.

In Wi-Fi, sub-6 GHz, and compact RF products, the antenna cable quietly determines whether a link holds higher data rates, stays within EIRP limits, and survives vibration and rework. Most field issues don’t come from cables that won’t screw on. They come from cables that do screw on—yet introduce loss, mismatch, or mechanical stress that only shows up later.

This guide focuses on what actually matters in practice:

how to identify SMA vs RP-SMA correctly, how to pair both ends of an sma antenna cable with minimal return risk, and how to choose lengths that stay stable at 5 GHz and 6 GHz without chasing ghosts during validation.

How do I tell SMA from RP-SMA in 10 seconds before ordering?

This chart is the core tool for quickly and accurately distinguishing between SMA and RP-SMA connectors. It divides connectors into four quadrants based on two key features (Thread location: internal/external; Center contact: pin/socket), corresponding to SMA Male, SMA Female, RP-SMA Male, and RP-SMA Female. The article emphasizes that intuitive assumptions like “antenna = male” are highly error-prone and identification must strictly follow this visual rule to avoid ordering mistakes and electrical mismatch.

Most ordering mistakes happen right here. Not because the standard is complicated, but because visual assumptions sneak in.

You do not need datasheets, calipers, or to open the enclosure. You only need to look at two things—always in this order:

- Where the threads are

- What the center contact looks like

Everything else is noise.

Thread × pin/hole quick ID (device vs antenna)

Use the four-quadrant check below. It works on device jacks, bulkheads, pigtails, and antennas.

- External thread + center pin → SMA male

- Internal thread + center socket → SMA female

- External thread + center socket → RP-SMA male

- Internal thread + center pin → RP-SMA female

That’s it.

A common mental trap is assuming that “antenna = male.”

That assumption fails immediately with RP-SMA, which deliberately reverses the center contact while keeping the thread familiar.

If you want a deeper background reference, the definition is covered in standard references such as the SMA connector overview, but for ordering purposes, the four-quadrant rule is faster and more reliable.

Look-alike trap: mechanical fit ≠ RF compatibility

One of the most expensive lessons teams learn is that thread engagement does not guarantee electrical correctness.

Certain SMA and RP-SMA combinations will feel like they almost fit. Some even fully tighten with the help of tolerances. The problem shows up electrically:

- Return loss degrades

- VSWR rises

- Higher-order modulation drops first

- Range looks fine at 2.4 GHz but collapses at 5 GHz or 6 GHz

If a system passes basic bring-up but struggles to hold throughput under load, mismatched SMA/RP-SMA connections are worth checking before touching firmware or antennas.

How should I pair both ends of an sma antenna cable to avoid returns?

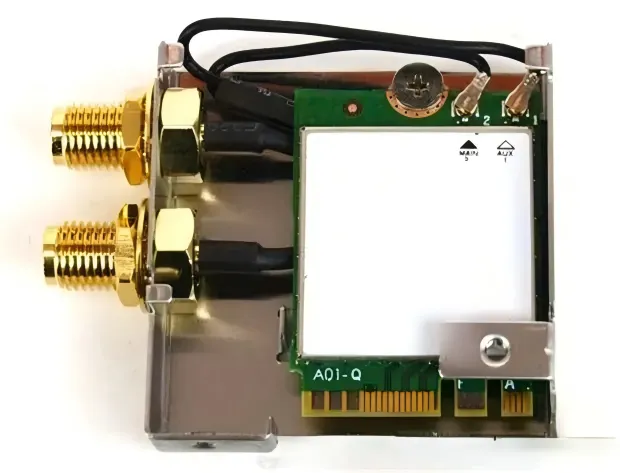

This is a close-up photo showing the IO bracket area of a PCIe expansion card (or a module of similar form factor). One or more SMA interfaces (most likely SMA female jacks) are clearly visible, possibly with an antenna connected or showing the surrounding metal shielding and mounting structure. This image serves to concretize the abstract concept of a “device port,” allowing readers to visually understand how SMA antenna connectors are integrated and used in actual PCIe hardware products such as Wi-Fi cards or IoT gateway modules, providing a real-world context for the subsequent discussion on cable pairing (e.g., running a cable from the SMA-F port of a PCIe card).

Once the port type is confirmed, the next risk is how many interfaces you stack.

Every additional interface—adapter, coupler, gender changer—adds loss and tolerance. In RF, those tolerances multiply faster than most people expect.

Typical chain: device SMA-F → cable SMA-M to SMA-F → antenna SMA-M

This is the most common low-risk pairing in real products:

- Device port: SMA-F

- Cable: SMA-M to SMA-F

- Antenna: SMA-M

Why this works well:

- No adapters in the signal path

- Clear mating direction

- Easy visual inspection during assembly

- Predictable insertion loss

From a warehousing perspective, this combination also reduces picking errors. There is one cable, one antenna, and no loose adapters that can be forgotten or swapped.

Boundary with rp-sma antenna: when to re-terminate or adapt

RP-SMA antennas are extremely common in Wi-Fi ecosystems, especially around routers and access points. Problems start when an RP-SMA antenna is paired with an SMA device port “just for testing.”

You have two options:

- Short-term / prototype:

Use a single SMA to RP-SMA adapter. Accept the added loss and keep it temporary.

- Production / validation:

Re-terminate the cable or switch the antenna to a native SMA version.

In production, adapting permanently is almost always the wrong choice. One adapter becomes two. Two become three. Before long, the link margin you thought you had is gone.

If you’re already comparing connector standards, the matching logic is discussed in more depth in RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching & Ordering Guide, which complements this article without overlapping its focus.

How long can I go at 5/6 GHz before throughput drops?

This is a high-quality comparison photo placing four key SMA/RP-SMA connectors (SMA Male, SMA Female, RP-SMA Male, RP-SMA Female) side by side. The image specifically highlights the two identification points: 1) Thread Location (on the external sleeve or inside the internal cavity); 2) Center Contact (protruding pin or recessed socket). It may include arrows or labels for annotation. This image is the visual core of the article's “10-second identification rule” and “four-quadrant rule,” designed to help engineers skip datasheets and, through direct visual observation, avoid confusing SMA and RP-SMA standards when ordering cables or antennas, thereby preventing electrical performance degradation due to interface mismatch.

Cable length is where theoretical comfort meets practical limits.

At low frequencies, an extra few decimeters rarely matter. At 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, they absolutely do—particularly inside compact enclosures where every connector and bend adds stress.

When sma extension cable / wifi antenna extension cable choices matter

You’ll see several names used interchangeably in catalogs:

- sma extension cable

- wifi antenna extension cable

- wifi antenna cable

The labels are marketing language. What matters is still the same three variables:

- Frequency

- Cable type

- Total electrical length including connectors

A “Wi-Fi” label does not change physics.

Length–Loss Estimator (engineering quick check)

Inputs

- Frequency: 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz

- Cable type: e.g., RG178

- Length (L): meters

- Number of intermediate connectors or adapters (n)

Rule-of-thumb formula

Estimated Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

- α depends on cable construction and frequency

- Each connector or adapter typically contributes ~0.2 dB

Outputs

- Recommended length tier (0.1 / 0.3 / 0.5 / 1 / 2 m)

- Expected throughput impact

- Optimization action: shorten, switch to lower-loss cable, or remove adapters

Practical length tiers (RG178, internal routing)

| Band | Conservative length | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | ≤ 1 m | Usually tolerant |

| 5 GHz | ≤ 0.5 m | Adapters start to hurt |

| 6 GHz | ≤ 0.3 m | Direct paths preferred |

These are not theoretical limits. They are experience-driven thresholds where teams stop chasing unexplained drops.

For a broader view of coax loss behavior across cable families, you can cross-reference the internal hub RG Cable Guide, which provides loss context without duplicating this article’s selection logic.

How do I spec a sealed SMA bulkhead for panel feed-through?

This schematic details a sealed SMA bulkhead assembly with an O-ring, including the connector body, washer, lock nut, etc., and may show a cross-sectional view of its installation on a metal or plastic panel. It is used to introduce discussions on key mechanical reliability issues such as bulkhead selection (round hole + anti-rotation key vs. flanged), O-ring compression, thread engagement, and torque control. The article emphasizes that bulkhead failures are mostly long-term mechanical issues rather than instant electrical faults, so they must be carefully designed and selected like mechanical fasteners.

Panel feed-throughs look deceptively simple. Drill a hole, insert a connector, tighten a nut.

In reality, this is one of the most failure-prone points in an RF enclosure.

A poorly specified SMA bulkhead doesn’t usually fail electrically on day one. It fails mechanically over time. Vibration loosens it. O-rings cold-flow. Threads gall. Eventually, the connector rotates just enough to stress the coax or compromise the seal.

That’s why bulkhead selection needs to be intentional, not an afterthought.

Hole size and anti-rotation: round + key vs 2-hole / 4-hole flange

There are two reliable approaches, and each fits a different enclosure style.

- Round hole with anti-rotation key

This is common in machined or molded housings designed specifically for RF connectors. The key prevents rotation without adding extra fasteners. Assembly is fast, but the enclosure must be designed for it.

- 2-hole or 4-hole flange bulkhead

This approach trades speed for robustness. The flange mechanically locks the connector to the panel, making it far more resistant to vibration and repeated mating cycles. In industrial or mobile equipment, this is often the safer choice.

What rarely works well is a plain round hole with no anti-rotation feature. Even if it survives initial testing, it tends to loosen in the field.

If you want a deeper, panel-focused breakdown, SMA Bulkhead: Panel Hole Size, Thread Length & Sealing expands on this topic without overlapping the cable-selection logic here.

O-ring compression, thread engagement, and torque discipline

Waterproofing failures almost never come from “bad O-rings.” They come from misuse.

Three rules hold up in practice:

- Moderate compression beats maximum compression

An O-ring should be compressed enough to seal, not crushed. Over-compression accelerates aging and reduces elasticity.

- Thread engagement matters more than torque

Full, clean thread engagement distributes load. Excess torque on partial engagement just damages threads.

- Anti-loosening beats over-tightening

A light thread-locking compound or a locking washer does more for long-term reliability than extra torque ever will.

When bulkheads fail in the field, the root cause is usually mechanical—not RF. Treat them like mechanical fasteners first, RF components second.

How should I route inside the chassis without stressing the coax?

By comparing correct and incorrect routing methods, this diagram visualizes several key internal routing guidelines: maintaining a generous bend radius (typically ≥10x cable OD), placing strain relief points before the connector, and avoiding tight contact with metal walls to maintain consistent impedance and reduce unpredictable ground paths. It emphasizes that seemingly neat assemblies can hide long-term reliability risks (e.g., fatigue, impedance mismatch), and good internal routing is fundamental to ensuring the cable’s long-term stable operation under vibration and temperature cycling.

Internal routing is where neat-looking assemblies quietly turn into long-term problems.

Coaxial cable does not like being forced. It tolerates gentle curves. It resists sharp decisions.

Bend radius rule (≥10× OD) and strain relief placement

The “10× outer diameter” rule isn’t conservative folklore. It’s a boundary between elastic deformation and long-term damage.

Bends tighter than that may work electrically at first, but they introduce:

- Impedance irregularities

- Shield deformation

- Accelerated fatigue near the connector crimp

Good routing does two simple things:

- Keeps bends smooth and gradual

- Places strain relief before the connector, not at it

A cable that is supported a few centimeters away from the SMA connector will outlast one that hangs freely and flexes at the joint.

Spacing from metal walls and EMI grounding hygiene

It’s tempting to press coax against a metal wall and assume “more shielding is better.” That assumption doesn’t always hold.

Very tight proximity to metal edges can:

- Alter the effective impedance locally

- Increase coupling at discontinuities

- Create unpredictable ground paths

In practice, leaving a small, consistent clearance and grounding intentionally—rather than accidentally—produces more repeatable results.

If EMI issues appear late in validation, routing is often a faster fix than changing antennas or radios.

Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack—what’s the penalty?

Short answer: yes.

Engineering answer: yes, but you pay for it.

Added loss vs compliance risk (EIRP)

Each adapter introduces additional insertion loss. As a working estimate, many teams budget ~0.2 dB per adapter.

That sounds small. It rarely stays that way.

Adapters tend to stack:

- One for gender

- One for standard (SMA to RP-SMA)

- One more because inventory had it on hand

At 5 GHz or 6 GHz, that stack shows up as reduced link margin. In regulated systems, it also pushes EIRP closer to compliance limits in unpredictable ways.

Mechanical compliance is easy to check. Radiated performance is not.

For regulatory context on how antenna gain and system output interact, general RF background references such as antenna fundamentals provide useful conceptual grounding—but they don’t replace system-level testing.

Prefer direct match, shorter runs, fewer adapters

If an adapter is unavoidable, treat it as temporary.

In production designs, the hierarchy of fixes is simple:

- Match connector standards directly

- Shorten the cable

- Remove intermediate adapters

Every step in that direction buys back margin that firmware and tuning cannot.

What belongs on my PO so warehousing won’t bounce it?

Most ordering delays don’t come from supply shortages.

They come from ambiguous purchase orders.

From a warehouse perspective, SMA-related returns are frustratingly predictable. The cable arrives. The length is right. The connector looks right—until someone checks the center contact and realizes the end type was never specified clearly.

A clean PO removes interpretation. It turns an RF cable from a guess into a deterministic part.

SMA antenna cable ordering checklist

| Field | What must be stated |

|---|---|

| Connector standard | SMA or RP-SMA (explicit) |

| Center contact | Pin or socket |

| End configuration | M-F, M-M, or F-F |

| Cable type | RG178, RG316, etc. |

| Length | Exact length (m or mm) |

| Bulkhead / flange | Yes/No; 2-hole or 4-hole |

| Sealing | O-ring / waterproof cap (Yes/No) |

| Quantity | Integer, not "as needed" |

Copy-ready PO note template

Use one line. Say everything once.

SMA-M to SMA-F antenna cable, RG178, 0.3 m, non-bulkhead, no adapter, with waterproof cap, Qty 50

This format scales. It works for prototypes and for pallets. Most importantly, it leaves no room for interpretation.

If your team already maintains connector-related purchasing standards, this checklist aligns cleanly with broader ordering guidance found in hub-style references like RG Cable Guide, without duplicating that material.

Frequently asked engineering questions

These questions reflect what engineers actually ask after first bring-up—not marketing FAQs.

How can I confirm SMA vs RP-SMA without opening the enclosure?

Check thread location first, then the center contact. External thread plus pin is SMA male; external thread plus socket is RP-SMA male. No disassembly required.

What length tiers are safe for 6 GHz with RG178 inside a compact chassis?

In practice, 0.3 m or shorter is the conservative limit, especially if any adapters are present.

Is one M–F jumper better than two back-to-back adapters?

Almost always. One continuous jumper removes two interfaces and reduces both loss and tolerance stack-up.

Can I pass EIRP compliance using an RP-SMA antenna on an SMA jack?

Sometimes, but margins shrink quickly. Each adapter changes both loss and radiated characteristics. Validate, don’t assume.

Final field notes: why this cable deserves more respect

An sma antenna cable doesn’t amplify signals.

It doesn’t decode packets.

It doesn’t run firmware.

Yet it sits at the intersection of mechanics, RF performance, and regulatory compliance. When it is chosen casually, it quietly erodes margin. When it is specified deliberately, it disappears—which is exactly what you want.

If you take nothing else from this guide, take this ordering mindset:

- Identify the connector standard correctly

- Minimize interfaces

- Keep length honest at higher frequencies

- Say everything once, clearly, on the PO

Do that, and this cable will stop being a variable in your system.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.