SMA Antenna Cable Length, Loss & Use Cases

Jan 21,2025

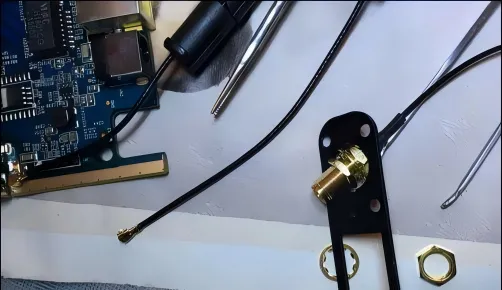

This image appears at the beginning to visually introduce the core argument—the mismatch between the importance of antenna cables and the attention they receive. It might be a contrasting image: the foreground clearly shows a Wi-Fi antenna (like a paddle or rubber duck) under discussion or test, with an engineer’s focus on it; in the background, an SMA antenna cable (perhaps coiled or tucked away) is blurred or unnoticed. This echoes the text: “the antenna gets most of the attention… the cable… is often treated as an afterthought,” aiming to shift this perception.

In many RF products, the antenna gets most of the attention. Engineers debate gain, radiation pattern, polarization, and placement. The cable that connects that antenna to the radio, however, is often treated as an afterthought.

That assumption usually holds—until it doesn’t.

In Wi-Fi routers, IoT gateways, and FWA CPEs, the sma antenna cable often becomes the quiet bottleneck in the RF link. It introduces loss, it sees mechanical stress, and it lives closer to the outside world than almost any other RF component. Understanding where this cable sits in the system, how long it can realistically be, and how to match it with the right coax family makes the difference between a link that barely passes and one that works reliably for years.

This guide focuses on practical engineering decisions. Not just theory, but how antenna cables behave in real products, real enclosures, and real deployments.

Where does an sma antenna cable sit in your RF link?

Distinguish sma antenna cables from generic sma cable runs

Following the subheading “Distinguish sma antenna cables from generic sma cable runs,” this should be an intuitive comparison image, possibly using a split-screen or side-by-side layout. The left side shows an external antenna cable: the connected antenna is being rotated or handled by a hand, the cable passes through an enclosure panel, and is exposed to potential temperature changes, vibration, or accidental pulls. The right side shows an internal jumper: it’s neatly secured between a PCB and an internal connector, inside a closed, dust-free, thermally stable device interior. Icons (e.g., a hand, thermometer, vibration symbol) might be used to emphasize the additional stress on the external cable, visually explaining why “many field failures attributed to ‘bad antennas’ trace back to antenna cables that were never designed for frequent handling.”

Electrically, many SMA cables look interchangeable. They share the same impedance, similar connectors, and comparable datasheet specs. That similarity is exactly why antenna cables are often underestimated.

A true sma antenna cable is usually exposed to conditions that internal sma cable runs never see. It sits closer to the enclosure wall, often passes through a panel bulkhead, and is handled repeatedly by users. Antennas are rotated, removed, upgraded, or replaced entirely. Every one of those actions applies torque and bending stress directly to the cable and its connectors.

Internal SMA jumpers, by contrast, are typically installed once and never touched again. They live in a relatively stable thermal and mechanical environment. Even if two cables use the same coax type, their real-world reliability profiles can be very different.

From experience, many field failures attributed to “bad antennas” or “unstable radios” trace back to antenna cables that were never designed for frequent handling. The electrical design may be correct, but the mechanical assumptions were not.

See how sma rf cable segments connect radio, enclosure, and antenna

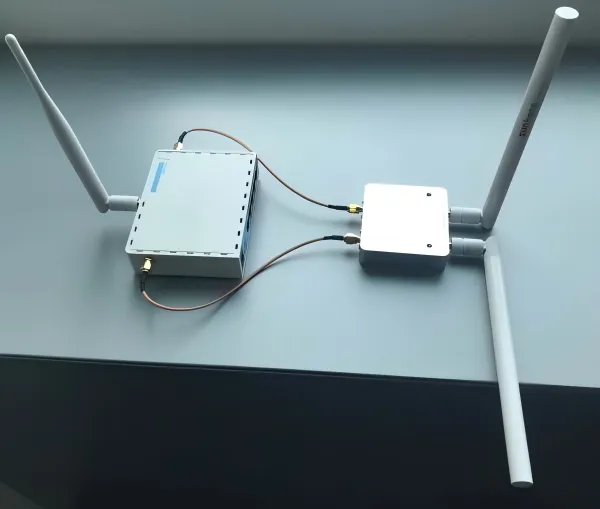

Following the subheading “See how sma rf cable segments connect radio, enclosure, and antenna,” this is likely a system block diagram or product exploded view that clearly shows the complete path from signal generation to radiation. From left to right, it might sequentially depict and label: RF Chipset/Module (on PCB), a short internal micro-coax or trace transition, an SMA bulkhead connector mounted on the metal enclosure (serving as a mechanical and electrical interface), an external SMA antenna cable, and finally the Antenna Element (e.g., rubber duck). Arrows or lines connect the segments, emphasizing this is an ordered “chain,” with the external antenna cable being the crucial bridge between the protected interior and free space.

In most products, the antenna connection is not a single uninterrupted cable. It is a chain of RF segments, each with a specific role.

A common architecture looks like this:

- RF chipset or module on the PCB

- Short internal micro-coax or trace transition

- SMA bulkhead mounted on the enclosure

- External sma rf cable or sma antenna cable

- Antenna element

This segmentation matters. The internal segment optimizes routing and impedance control. The bulkhead defines a mechanical interface and reference plane. The antenna cable bridges the protected interior to free space.

Problems arise when these segments are treated as interchangeable. For example, extending the external antenna lead without revisiting loss budgets often shifts the dominant loss from the radio front end to the feeder itself. In compact IoT gateways or SDR platforms, a seemingly small change in antenna cable length can move the system from “comfortable margin” to “barely working.”

If you want a broader view of how SMA cabling fits into mixed RF paths, the overview in SMA RF cable selection for mixed RF and antenna systems provides useful context before narrowing the focus to antenna-specific runs.

Decide when the antenna lead—not the antenna—is limiting your link budget

One of the most common RF troubleshooting mistakes is blaming the antenna first.

When range is shorter than expected or throughput drops earlier than simulations predict, antennas become the default suspect. In practice, the sma antenna cable often deserves the first look.

A simple diagnostic approach works surprisingly well: temporarily replace the existing antenna cable with a much shorter one. If RSSI or SNR improves noticeably without changing the antenna, the feeder was consuming more link budget than expected.

This effect becomes more pronounced at higher frequencies. At 5 GHz and above, every extra decimeter of sma coax cable matters. Connector losses add up as well. Two or three additional SMA interfaces can quietly erase several dB of margin, especially when tolerances stack up.

Before redesigning antennas or RF front ends, isolate the antenna cable variable. In many cases, shortening or upgrading the cable solves the problem immediately.

How do you choose coax types for sma antenna runs?

Compare sma coaxial cable options: RG316, RG174, LMR-100, and beyond

Choosing a coax family for antenna leads is always a trade-off between loss, flexibility, and survivability.

Below is a high-level comparison engineers commonly use during early planning:

| Cable family | Typical outer diameter | Flexibility | Relative attenuation | Typical antenna use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG316 | ~2.5 mm | High | Higher | Short runs, hot or dense enclosures |

| RG174 | ~2.8 mm | Very high | Higher | Tight routing, low mechanical load |

| LMR-100 | ~2.8 mm | Medium | Lower | Short outdoor feeders |

| LMR-200 / 240 | ~4.9-6.1 mm | Low | Much lower | Longer antenna runs |

RG316 is widely used because it tolerates heat and vibration well. Its PTFE dielectric and double shielding make it robust near power amplifiers and switching regulators. The trade-off is higher attenuation per meter.

LMR-style cables reduce loss significantly, but they are stiffer and less forgiving mechanically. Once routed, they tend to stay put. That’s an advantage for fixed outdoor feeders, but a disadvantage near user-accessible antenna ports.

For a deeper comparison of RG and LMR families across applications, the 50-ohm RG and LMR cable comparison guide provides a useful reference.

Match sma antenna cable length tiers to cable families

Thinking in length tiers helps avoid over-optimization.

- Short runs (below 0.3 m)

Loss is rarely the limiting factor. Mechanical flexibility and temperature rating dominate. RG316 is usually the safest choice.

- Medium runs (0.3–1 m)

Common in small access points, CPEs, and gateways. RG316, RG174, or LMR-100 can all work, depending on frequency and available margin.

- Longer runs (above 1 m)

Loss becomes unavoidable. At this point, thicker sma rf cable families or hybrid solutions make more sense than extending thin coax indefinitely.

This tiered approach prevents using overly thick cables where they add no benefit, and prevents thin cables from silently degrading higher-frequency links.

Balance flexibility, loss, and temperature around hot RF enclosures

Datasheets rarely capture the full thermal reality of deployed products.

Near RF power amplifiers, DC-DC converters, or sealed enclosures exposed to sun load, temperatures can climb higher than expected. In these environments, RG316-based sma coaxial cable often outperforms thicker, lower-loss alternatives simply because it survives longer.

Many teams discover this only after field returns show drifting VSWR or intermittent failures. The lesson is straightforward: a slightly higher-loss cable that remains stable over time is often preferable to a theoretically better cable that degrades under heat or vibration.

How can you plan sma antenna cable length and loss?

Before introducing a formal planner, it helps to establish realistic loss expectations.

At a system level, antenna feeders rarely get an unlimited budget. They compete with filters, matching networks, and environmental variability. For most Wi-Fi and sub-6 GHz systems, engineers converge on practical limits rather than absolute theoretical ones.

A commonly used guideline is:

- 2.4 GHz links: keep total antenna path loss under roughly 6–8 dB

- 5–6 GHz links: aim for 4–6 dB or less

These figures include both cable attenuation and connector losses. Exceeding them doesn’t guarantee failure, but it does reduce margin for fading, interference, and manufacturing variation.

Most RF teams don’t fail because they miscalculate something. They fail because no one ever wrote down a realistic limit.

Antenna cables are a good example. On the whiteboard, loss budgets look generous. In a finished product, that margin disappears fast—filters, matching networks, enclosure effects, connector tolerances, and real-world fading all take their share.

That’s why experienced engineers tend to work with rough but conservative rules instead of chasing perfect numbers.

Set practical loss budgets for 2.4, 5, and 6 GHz antenna links

In everyday Wi-Fi and sub-6 GHz systems, antenna feeders rarely deserve more than a small slice of the total link budget.

A common field-tested guideline looks like this:

- 2.4 GHz

Try to keep the entire antenna path—cable plus SMA connectors—within 6 to 8 dB.

- 5 GHz / 6 GHz

Once you move up in frequency, tolerance shrinks. 4 to 6 dB is a more realistic ceiling.

These numbers aren’t pulled from a standard. They come from watching what happens when margin runs out. Higher-order modulation schemes behave well right up until they don’t, and when feeder loss is the culprit, performance drops off a cliff instead of fading gracefully. That behavior is consistent with how modern wireless links trade robustness for capacity, something that’s easy to forget if you mostly look at datasheets instead of deployed systems.

Approximate per-meter loss for common sma antenna cable families

Early in a design, you don’t need tenth-of-a-decibel accuracy. What you need is a sense of scale.

Engineers usually work with rounded, slightly pessimistic values like these:

| Cable family | ~2.4 GHz | ~5 GHz |

|---|---|---|

| RG316 | ~1.2 dB/m | ~2.2 dB/m |

| RG174 | ~1.5 dB/m | ~2.8 dB/m |

| LMR-100 | ~0.7 dB/m | ~1.3 dB/m |

| LMR-200 | ~0.35 dB/m | ~0.65 dB/m |

These figures already assume real routing, not an ideal straight cable in free space. Tight bends, connector transitions, and manufacturing spread are implicitly baked in. If a design only works on paper with “best-case” loss numbers, it probably won’t survive first production.

If you want a wider view of how these cable families compare beyond antenna use, the overview in the 50-ohm RG and LMR cable comparison guide gives useful background.

Build a practical SMA Antenna Cable Length & Loss Planner

Instead of debating cable choices case by case, it helps to turn the decision into a repeatable check. This planner is intentionally simple—it’s meant for design reviews, quick sourcing calls, and sanity checks, not lab reports.

Inputs

- Frequency_GHz

Typical values: 2.4, 5, 5.8, 6

- Cable_family

RG316 / RG174 / LMR-100 / LMR-200

- Length_m

Total antenna cable length

- Connector_pairs

Count full SMA pairs along the antenna path

(radio to bulkhead = one pair, bulkhead to antenna = one pair)

- Max_allowable_loss_dB

How much loss the system can tolerate for the antenna feeder

Look-up values

- Loss_per_m_dB

Taken from typical attenuation ranges for the chosen cable

- Connector_loss_per_pair_dB

A practical default is 0.15–0.2 dB per SMA pair.

That aligns well with what most teams measure in everyday test setups, not just in controlled lab conditions.

Tier interpretation

- Margin ≥ 3 dB → Comfortable

Enough headroom for tolerances and environment.

- 0 to 3 dB → Tight

Works, but avoid extensions, adapters, or last-minute changes.

- Below 0 dB → Not recommended

Shorten the cable or move to a lower-loss family.

Walk through two real sma antenna cable cases

Case 1: 2.4 GHz home router

- RG316

- 0.3 m length

- 2 SMA connector pairs

- 6 dB allowable loss

Cable loss ≈ 0.36 dB

Connector loss ≈ 0.30 dB

Total ≈ 0.66 dB

This is why short RG316 antenna leads almost never limit indoor Wi-Fi performance.

Case 2: 5.8 GHz outdoor CPE

- LMR-200

- 1.0 m length

- 2 SMA connector pairs

- 4 dB allowable loss

Cable loss ≈ 0.65 dB

Connector loss ≈ 0.30 dB

Total ≈ 0.95 dB

The same length with RG174 would push the system close to the edge. On paper it might still “work,” but field margin would be thin.

How do you keep sma antenna cables mechanically reliable over time?

Use sma male to sma female cable deliberately at panel interfaces

A sma male to sma female cable is often treated as an afterthought, but it solves a very real problem: torque.

By fixing the male connector at the radio side and presenting a female interface at the enclosure wall, you prevent users from twisting the PCB connector every time they touch the antenna. Over months or years, that difference matters far more than a small change in insertion loss.

This approach is especially useful in products where antennas are user-replaceable or frequently adjusted.

Route sma coax cable to avoid stress you’ll never see in CAD

Most cable failures don’t happen in the middle of a run. They happen right behind the connector.

Sharp bends, pinched sections, and forced twists concentrate stress exactly where the shield and center conductor are weakest. A short service loop near the antenna interface, a smooth bend radius, and basic edge protection eliminate a large class of intermittent field issues.

These details rarely show up in schematics, but they show up in RMAs.

Protect sma antenna cables from heat, vibration, and moisture

Environmental stress accumulates quietly.

Heat accelerates dielectric aging. Vibration works the shield until it cracks. Moisture changes impedance long before corrosion is visible. In outdoor or vehicle-mounted systems, adding strain relief and controlled routing often does more for long-term RF stability than choosing the “best” cable on paper.

If you step back and look at antenna systems from a system-level perspective—as outlined in broader discussions of antenna systems and feeds—it becomes clear that mechanical design and RF performance are tightly coupled, whether we like it or not.

Where are sma antenna cables used across Wi-Fi, IoT, and FWA?

Follow sma antenna cables inside home Wi-Fi routers and mesh systems

In most home routers and mesh access points, antenna cables are short, cheap, and rarely questioned. That simplicity is misleading.

A typical consumer router uses one sma antenna cable per radio chain, routed from the RF section on the PCB to a panel-mounted SMA connector, and then to a rubber duck or paddle antenna. The length is usually well under half a meter, which keeps loss manageable even with thinner coax.

The hidden constraint is mechanical, not electrical. These devices live in homes where antennas get repositioned, bumped, or replaced. Over time, that repeated interaction stresses the antenna lead far more than an internal jumper ever would. That’s one reason RG316 and RG174 remain popular in this space despite their higher attenuation—they survive handling better.

As Wi-Fi generations evolve, the basic architecture stays the same, but margin shrinks. The antenna cable that was “good enough” for Wi-Fi 4 often becomes marginal for later standards, even when nothing else in the design changes.

Use sma rf cable in IoT gateways, industrial routers, and SDR gear

IoT gateways and industrial routers tend to blur the line between consumer and infrastructure hardware. They are often installed once and expected to run unattended for years, sometimes in harsh environments.

In these systems, the sma rf cable between enclosure and antenna is no longer just a convenience. It’s a reliability component. Vibration, temperature cycling, and exposure all matter. Engineers often choose cable families based as much on mechanical robustness as on insertion loss.

SDR platforms add another twist. Antennas are swapped frequently during development and testing. A poorly chosen antenna cable can become the first failure point, even when the radio itself is solid. That’s why many SDR users quietly standardize on a small set of antenna cable lengths and types instead of improvising with adapters.

For teams working across multiple RF products, it helps to keep antenna-specific decisions aligned with broader SMA practices, such as those discussed in SMA RF cable selection for mixed RF and antenna systems.

Support 5G FWA CPE and outdoor installs with robust antenna leads

Fixed wireless access changes antenna assumptions.

Instead of placing antennas where it’s convenient, FWA deployments place them where propagation is best—on rooftops, walls, or poles. That shift increases both antenna cable length and exposure. A sma antenna cable that works fine indoors may struggle once it’s routed through an exterior wall or mounted near a roofline.

As a result, many FWA CPE designs use a hybrid approach: a short, flexible RG316 or RG174 segment near the radio, transitioning to a thicker low-loss feeder for the longer outdoor run. This keeps stress off the radio connector while preserving link margin.

As FWA deployments continue to grow, antenna cables are no longer peripheral components. They become part of the system’s long-term reliability strategy.

How are Wi-Fi 7 and 5G trends changing antenna cable decisions?

See how Wi-Fi 7 tightens loss and VSWR tolerance

Wi-Fi 7 doesn’t fail gently.

With wider channels and higher modulation orders, small degradations in SNR have outsized effects on throughput. A few extra decibels of loss in an antenna cable can turn a “fast but stable” link into one that constantly rate-shifts.

What changes is not the connector or the coax type, but the tolerance for sloppiness. Antenna cables that were once selected by habit now need to be checked against real loss budgets. The basic physics hasn’t changed, but the system sensitivity has.

This aligns with broader trends in wireless evolution, where efficiency gains come at the cost of tighter RF margins, a pattern visible across modern standards described in general discussions of wireless communication systems.

Understand how 5G FWA shifts antenna placement and feeder length

5G FWA pushes antennas outward.

To reach customers beyond fiber coverage, providers rely on outdoor placement and line-of-sight improvements. That often means antennas mounted higher and farther from the radio unit. The result is longer feeders and more demanding antenna cable requirements.

Design teams increasingly accept that thin coax is no longer sufficient for the full run. Instead, they plan for transitions: thicker feeders where loss dominates, and short flexible segments where mechanical stress dominates. The sma antenna cable becomes a defined interface, not an improvised link.

Align sma antenna cable SKUs with evolving RF front-end layouts

Following the subheading “Align sma antenna cable SKUs with evolving RF front-end layouts,” this should be a product-oriented image. It might show a modern, highly integrated RF front-end PCB with carefully planned SMA connector locations. Neatly arranged beside it are 2-3 standardized SMA antenna cables of different lengths/types, each with clear labeling (e.g., “SKU101: LMR-200, 1m, SMA Male to Female”). Dotted lines or icons might indicate how these standard cables match different connector locations on the PCB. This image embodies a shift in design thinking from ad-hoc selection to standardized, modular part management, addressing the stricter layout requirements and faster product iteration driven by trends like Wi-Fi 7 and 5G FWA.

RF front ends are becoming denser and more integrated. Filters, LNAs, and PAs move closer together, and connector locations shift as layouts evolve.

Teams that predefine two or three standard antenna cable SKUs—each with known length, cable family, and connector configuration—adapt faster to these changes. Instead of redesigning the antenna path for every SKU variant, they swap between known-good antenna leads.

Over time, this kind of standardization reduces both engineering churn and field mistakes.

How can you standardize sma antenna cable parts, tests, and documentation?

Create a unified spec template for antenna cables

A simple template prevents ambiguity later. Most teams include:

- Target bands and use case (Wi-Fi, LTE, 5G, GNSS)

- Cable family (RG316, RG174, LMR-100/200)

- Nominal length and tolerance

- Connector genders and orientations

- Target insertion loss or VSWR at key frequencies

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s clarity.

Define basic acceptance checks for incoming antenna leads

Antenna cables rarely justify full swept measurements on every batch. Still, minimal checks catch most issues:

- Length verification

- Visual inspection of crimps and jackets

- Basic continuity and shield checks

- Spot S21 measurements on a small sample

Clear pass/fail criteria keep borderline parts from slipping into production.

Document installation and field-service rules explicitly

Many antenna problems start in the field, not the factory.

Installation guides should state which antenna cables are approved, which lengths are acceptable, and which substitutions are not. Clear guidance prevents technicians from extending cables with random adapters or replacing them with visually similar but electrically different parts.

Frequently Asked Questions

Do I really need a specific sma antenna cable, or will any SMA cable work?

Electrically, many SMA cables look similar. Mechanically and over time, antenna leads see far more stress. Treating them as generic cables often leads to premature failures.

How long can an sma antenna cable be before it hurts Wi-Fi range?

There’s no single cutoff, but once total feeder loss exceeds roughly 6–8 dB at 2.4 GHz or 4–6 dB at 5/6 GHz, range and throughput degrade quickly.

Is RG316 always better than RG174 for antenna use?

Not always. RG316 handles heat and vibration better, while RG174 offers more flexibility. The right choice depends on environment and length.

When should I use a sma male to sma female cable?

When you want to protect the radio-side connector and move all user interaction to the outside of the enclosure.

Can I join two antenna cables with an SMA adapter?

You can, but each additional interface adds loss and potential VSWR issues. For critical links, a single correct-length cable is usually better.

How should antenna cables be labeled for installers?

Including band, length, and cable family near the connector helps prevent mix-ups in the field.

Are sma antenna cables still relevant if a product uses internal antennas?

Yes. Many platforms later introduce external-antenna variants. Planning antenna cable strategy early makes those transitions easier.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.