Schottky Diode Practical Applications and Design Guide

Dec 26,2025

This figure serves as the introductory graphic for the document, acting as a guiding schematic to visually present the common locations of Schottky diodes in a complete hardware design. It likely depicts Schottky diodes quietly situated near connectors, regulators, or signal pins, echoing the point made at the beginning of the document: although easily overlooked during schematic design, these components often determine the robustness, efficiency, and signal integrity of a product in practice, and are key to preventing circuits from operating at their limits or exhibiting anomalous behavior.

A schottky diode usually doesn’t get much attention when a circuit is first sketched. It sits quietly near a connector, a regulator, or a signal pin, looking interchangeable with half a dozen other diodes in the parts drawer. Yet in finished hardware, these parts often end up deciding whether a product behaves politely—or spends its life flirting with edge cases.

Most engineers don’t learn this from datasheets. They learn it after a board comes back warm for no obvious reason, or when a signal that looked clean in simulation starts misbehaving once cables, temperature, and real switching edges enter the picture. Swap a PN rectifier for a Schottky and efficiency improves. Replace a slow clamp with a fast Schottky and ringing softens. Add a small Schottky near an interface pin and unexplained latch-ups disappear. These aren’t abstract effects; they show up on the bench.

This article focuses on how schottky diodes are actually used in working designs, not how they’re categorized in theory. We start from application roles, then move into symbols, polarity, and the schottky diode characteristics that genuinely affect power paths and signal integrity. A recurring reference is BAT46WJ, not because it is special, but because it represents a class of small-signal, high-voltage Schottky diodes that are frequently misapplied as “tiny rectifiers.” For readers dealing with polarity-sensitive paths, this discussion aligns naturally with practical protection topics covered in Reverse Polarity Protection Diode Design Guide and Reverse Polarity Protection Circuit Design Guide.

How can you quickly map schottky diode use cases?

In day-to-day design work, engineers rarely think in terms of device families. They think in terms of roles. A schottky diode may appear across power, protection, and signal sections of a schematic, but the intent behind each placement is usually very different.

Rectifier diode / schottky rectifier diode.

When efficiency matters at low voltage, a schottky rectifier diode is often the first upgrade from a standard rectifier diode. The lower forward drop reduces conduction loss directly, which is why Schottkys dominate 3.3 V and 5 V rails. The tradeoff—higher leakage and lower reverse-voltage capability—is usually acceptable in tightly controlled DC environments.

Flyback diode.

Any switched inductance needs a safe discharge path. A flyback diode provides it. In this role, reverse recovery behavior often matters more than absolute current rating. Schottky diodes are attractive at low to moderate voltages because they recover almost instantly, reducing switching loss and limiting voltage overshoot.

Clamping diode.

A clamping diode is not meant to conduct continuously. It waits for a fault or transient and then intervenes briefly. Schottkys are common here because they conduct early and respond quickly, making them suitable for MOSFET gate protection, interface pins, and sensitive analog inputs.

Signal diode.

In detection, envelope tracking, or waveform shaping, a signal diode must be fast and predictable. Current is modest; capacitance and recovery behavior dominate. Small-signal Schottkys are often chosen because they introduce minimal delay and distortion compared with PN devices.

Across these roles, the same fundamental contrast applies. Compared with a conventional PN rectifier, a schottky diode offers lower forward voltage and negligible reverse recovery, while accepting higher leakage and limited reverse-voltage headroom. This is exactly where BAT46WJ sits. With a 100 V reverse rating, a forward current rating of 250 mA, a forward drop around 0.85 V at rated current, and a reverse recovery time measured in nanoseconds, it clearly belongs to the small-signal Schottky category rather than power rectification. Manufacturer guidance from Nexperia and distributor data from DigiKey consistently position devices like this in signal conditioning, light protection, and auxiliary roles rather than main rectifier stages.

How should you read the schottky diode symbol and real-world polarity marks?

On paper, a schottky diode symbol looks almost identical to that of an ordinary diode. The difference is subtle: the cathode line is stylized or bent to indicate a metal–semiconductor junction. On a crowded schematic, that distinction is easy to miss, and in simple circuits it rarely causes trouble.

Problems tend to appear when designs become layered. Protection networks that mix Schottky clamps, Zener references, and TVS devices rely heavily on correct polarity assumptions. Confusing one symbol for another can quietly undermine an otherwise sound protection strategy.

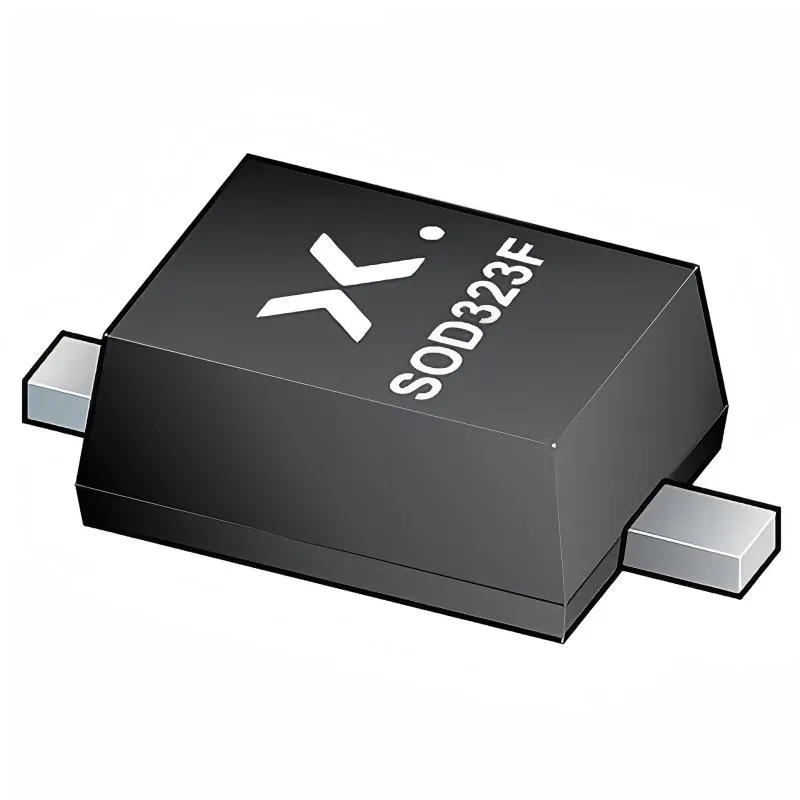

Even when the schematic is correct, real-world polarity mistakes often happen at the PCB level. Small packages such as SOD-323F rely on laser markings or chamfers to indicate the cathode. On BAT46WJ, the cathode stripe must align with both the schematic symbol and the footprint pin mapping.

A pattern that shows up repeatedly in design reviews is frustratingly consistent: the schematic is correct, the BOM lists the intended part, but the footprint library has the pins reversed. Once assembled, a flipped schottky diode in a tiny package may pass visual inspection and only reveal itself through abnormal leakage, unexpected heating, or protection paths that simply do not work.

Designers who have been burned by this tend to reinforce polarity visually. Align the silkscreen cathode mark with the package marking and keep it outside the copper pads. Automated optical inspection systems are far more reliable when silk and package cues agree.

Which schottky diode characteristics actually matter for power and signal integrity?

This figure serves as a physical reference image for the SOD-323F package devices discussed in the document. It is likely a close-up photo of a BAT46WJ or similar Schottky diode, clearly showing the actual dimensions, form factor, and crucial polarity marking (such as the laser stripe or chamfer indicating the cathode) of this small surface-mount package (SOD-323F). This image supports the textual discussions on “how to read real-world polarity marks” and “SOD-323F layout,” providing readers with an intuitive visual reference to understand the importance of correct identification and placement of such components in PCB design and miniaturized assembly.

Datasheets can be overwhelming, but only a handful of parameters consistently shape real-world behavior. Understanding these characteristics in context helps avoid misusing otherwise excellent parts.

Reverse voltage (VR).

Reverse rating is a hard boundary. BAT46WJ’s 100 V capability is not intended for high-voltage rails; it provides margin against transients. Cable inductance, hot-plug events, and switching edges can all push nodes well beyond their nominal levels. Many engineers design with a two-times peak-voltage guideline to keep Schottkys safely out of avalanche operation.

Forward current (IF).

Average current ratings tell you where a device does not belong. A 250 mA rating makes it clear that BAT46WJ is not a power rectifier. Instead, it fits roles where conduction is brief or limited: signal clamps, auxiliary flyback paths, or light reverse-polarity assistance.

Forward voltage (Vf).

Forward voltage defines conduction loss and clamp behavior. The relationship is simple—Vf multiplied by average current—but the consequences are not. In low-voltage logic rails, tens of millivolts matter. In protection paths, Vf determines how early a clamp begins to conduct and how much stress it diverts.

Reverse leakage (IR).

All Schottkys leak, and leakage increases rapidly with temperature. In high-impedance nodes or always-on systems, this can shift bias points or inflate standby power. It is often overlooked early and only noticed during thermal testing.

Reverse recovery and capacitance.

With a reverse recovery time on the order of a few nanoseconds, BAT46WJ behaves almost like an ideal diode compared with many fast recovery diodes that still store charge. Its modest junction capacitance keeps it usable in fast digital and RF-adjacent signal paths without excessive loading.

At a system level, while high-power automotive and EV designs increasingly rely on SiC Schottky devices, small-signal silicon Schottkys remain indispensable on the board, quietly shaping signals and absorbing fast transients where power levels are modest but timing is critical.

Schottky vs Fast Recovery vs Zener Selection and Loss Matrix

Engineers don’t usually argue about diodes in abstract terms. The disagreement almost always starts when something on the board runs hotter than expected, or when a scope trace refuses to calm down. At that point, names like schottky diode, fast recovery diode, or zener diode stop being categories and start becoming suspects.

The table below exists for that moment. It doesn’t rank devices. It simply puts typical numbers next to typical roles, using representative parts such as BAT46WJ to anchor the discussion in reality rather than preference.

| Device | Technology | VR (V) | IF (A) | Vf @ IF | trr (ns) | IR @ VR | Cd (pF) | Package | Common Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAT46WJ | Schottky diode | 100 | 0.25 | ~0.85 V | ~5.9 | µA range | 21-39 | SOD-323F | signal diode, clamping diode |

| FR107 | Fast recovery diode | 1000 | 1.0 | ~1.1 V | ~500 | low | high | DO-41 | flyback diode |

| BZX55-5V1 | Zener diode | 5.1 | — | — | — | — | — | DO-35 | voltage clamp |

On paper, the math is trivial. Conduction loss follows P = Vf × I_avg. Leakage loss grows with VR × IR, usually showing up only once temperature rises. Switching loss becomes visible when reverse recovery charge meets real switching frequency. What matters is not the formula, but which term dominates your board.

In low-voltage rails, conduction loss shows up immediately as heat. In flyback paths, reverse recovery decides how much ringing you’ll see. In protection networks, the question is rarely loss at all—it’s whether the clamp reacts before the silicon downstream does.

Once those questions are answered honestly, the device choice usually makes itself.

How should you choose between a rectifier diode and a schottky rectifier diode in rectifier designs?

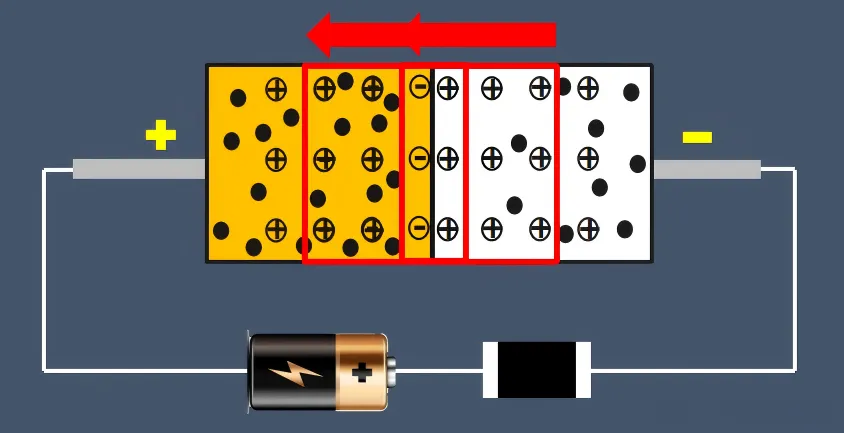

This figure appears in the discussion of rectifier diode selection in Section 7. It is not a simple schematic but rather likely an operational diagram combining current flow arrows with thermal distribution(or simulated thermal imaging). This image visually demonstrates how current flows through the diode during rectifier operation and how the resulting power loss (e.g., I × Vf) translates into localized heat. Its purpose is to visualize the core practical insight emphasized in the text: “if the diode is expected to run warm in steady state, it probably shouldn’t be a small-signal Schottky.” It helps designers understand the importance of thermal evaluation and component selection in rectification applications.

Rectifier choices are often made too early and revisited too late. Many designs start with a generic rectifier diode simply because it feels safe. Sometimes that’s the right call. Often, it’s just habit.

A conventional rectifier tolerates abuse well. High reverse voltage, thermal stress, and occasional overload rarely kill it outright. That robustness is why it still dominates mains rectification and high-voltage DC rails.

A schottky rectifier diode plays a different game. It trades voltage headroom for lower forward drop. On a 5 V or 3.3 V rail, that trade is almost always favorable. On a 24 V rail, it may not be.

This is where misunderstandings creep in. Not every schottky diode is a rectifier, and not every Schottky belongs anywhere near an AC input. BAT46WJ is a good example. Its current rating and package size make its limits obvious once you stop reading the name and start reading the numbers. It can clean up small DC paths, bias networks, or auxiliary rectification. It cannot replace a power rectifier, and it was never meant to.

A simple rule that holds up surprisingly well: if the diode is expected to run warm in steady state, it probably shouldn’t be a small-signal Schottky. If it only conducts briefly or lightly, then a Schottky may be exactly what you want.

How do you choose between schottky and fast recovery diodes in flyback and clamping roles?

Flyback paths and clamps tend to expose diode weaknesses quickly. Inductors are honest that way.

In a flyback diode role, voltage stress sets the outer boundary. If the reverse voltage is high, a fast recovery diode is often the only practical option. Its recovery isn’t ideal, but it survives. When voltage is moderate, a schottky diode often produces cleaner switching simply because it doesn’t store charge that has to be removed later.

That difference shows up on the scope long before it shows up in thermal calculations.

Clamping is a different problem. A clamping diode doesn’t care about efficiency. It cares about timing. It needs to turn on before the protected node crosses a dangerous level. Schottkys are popular here for a reason: low forward drop and fast response mean the clamp engages early.

Zeners complicate the picture. They add predictability but respond more slowly and dissipate more energy once active. In many real designs, the solution is not either–or, but both: a Schottky to catch fast edges, backed by a Zener to define a hard ceiling.

BAT46WJ tends to land comfortably in this mixed territory. Its voltage rating gives margin, its recovery time avoids additional ringing, and its capacitance stays low enough not to distort nearby signals. Used this way, it complements higher-energy protection parts rather than competing with them, a pattern also discussed in system-level protection notes such as Reverse Polarity Protection Circuit Design Guide.

How should you design and lay out BAT46WJ-class SOD-323F devices in signal diode applications?

Once a schottky diode is used as a signal diode, placement stops being a minor detail and starts becoming the design itself. At this scale, parasitics are no longer abstract. A few millimeters of trace or an oversized pad can easily dominate the diode’s electrical behavior.

Devices like BAT46WJ tend to appear in signal chains where current is limited but edge speed is not. Envelope detection, logic-level clamping, line termination helpers, and waveform shaping all fall into this category. In these cases, junction capacitance and recovery behavior matter far more than current rating. A diode that looks fine on paper can quietly distort edges or delay clamping simply because it sits too far from the node it is meant to protect.

The electrical reasons are straightforward. Extra trace length adds inductance, which delays conduction during fast transients. Larger copper areas increase parasitic capacitance, loading the signal and softening edges. Both effects become visible once rise times drop into the nanosecond range. This is why a Schottky clamp placed “nearby” often behaves very differently from one placed directly at the pin.

Polarity handling deserves equal attention. In SOD-323F packages, the cathode marking is small, and silkscreen mistakes are easy to make. A reversed small-signal Schottky rarely fails dramatically. Instead, it leaks, clamps late, or behaves inconsistently across temperature. These are the failures that consume the most debugging time because nothing looks obviously wrong.

Designers who have seen this once tend to treat small-signal Schottkys the same way they treat high-speed passives: tight placement, short loops, clean return paths, and unambiguous polarity marking. That discipline usually matters more than the exact part number.

How should you draw the line between schottky diode vs zener diode for protection and regulation?

The discussion around schottky diode vs zener diode is often framed as a choice, but in practice it is more accurately a boundary. Each device addresses a different failure mode, and problems begin when one is expected to solve the other’s problem.

A Schottky diode reacts quickly. It conducts early, limits fast excursions, and does so with very little delay. What it does not do is define a precise voltage. A Zener diode does the opposite. It establishes a relatively stable clamp level, but it reacts more slowly and dissipates more energy once active.

Because of this, many practical protection networks quietly use both. A Schottky handles fast edges before they propagate into sensitive silicon. A Zener defines the absolute ceiling once the transient lasts long enough to matter. Timing versus accuracy is the real distinction, not performance versus quality.

BAT46WJ fits naturally into the fast-edge side of this boundary. In logic protection, interface clamping, or light reverse-polarity assistance, it can steer current away from vulnerable nodes without adding much capacitance. Once surge energy rises beyond what a small-signal Schottky should absorb, the design has crossed into Zener or TVS territory regardless of preference.

The most common mistake is expecting a Schottky to behave like a precision regulator, or expecting a Zener to react like a fast switch. When each device stays within its natural role, protection circuits tend to become simpler and more predictable.

How do you verify, test, and accept schottky diode designs at the product level?

Verification is where assumptions finally meet hardware. A schottky diode that looks ideal on a datasheet can still behave differently once temperature, tolerances, and real waveforms enter the picture.

Bench testing usually begins with direct measurements. Forward voltage should be checked at the actual operating current, not only at datasheet reference points. Leakage should be measured at elevated temperature, because that is where Schottkys reveal their character. A device that appears quiet at room temperature may quietly draw more current than expected at 85 °C.

Thermal observation follows naturally. Even small-signal packages can warm quickly if conduction or leakage is underestimated. Infrared imaging or a simple thermocouple often shows whether a diode is operating comfortably or living on borrowed margin.

Application-level tests tend to be more revealing than component-level checks. In rectification paths, efficiency and waveform shape usually tell the story. In flyback diode or clamping diode roles, the oscilloscope shows whether voltage spikes are truly being limited or merely reshaped. In signal diode applications, linearity and distortion are often the deciding factors.

For production acceptance, clarity matters more than exhaustiveness. BOM notes should specify reverse voltage class, forward current expectations, forward drop range, and package type rather than listing only a part number. That single step prevents many substitution-related failures during sourcing and manufacturing.

FAQ

How do I choose a Schottky rectifier diode for low-voltage, high-current DC outputs?

When current is high and voltage is low, the decision usually starts with heat, not theory. A Schottky rectifier diode is attractive because its lower forward voltage directly reduces conduction loss, which shows up immediately on the thermal image. That said, the current rating alone is not enough. You need to look at how Vf rises with current and temperature, not just the headline value.

Reverse-voltage margin still matters, even on low-voltage rails. Spikes from cables, connectors, or inductive loads can exceed nominal levels. Package size and thermal resistance often become the limiting factors before the silicon does. If the diode is expected to conduct continuously, it should be physically sized so it never feels “warm but acceptable.” In practice, that usually means it is already too small.

What do the Schottky diode symbol markings on tiny SMD packages like SOD-323F actually mean?

On schematics, Schottky symbols differ only slightly from standard diode symbols, which makes mistakes easy. On tiny packages like SOD-323F, the physical marking matters more than the drawing. The cathode is typically indicated by a laser stripe or chamfer, not by pin numbers that are visible after assembly.

Problems often arise when footprint libraries are reused without verifying polarity conventions. The schematic can be correct, the BOM correct, and the board still wrong. Once assembled, a reversed small-signal Schottky may not fail catastrophically. Instead, it leaks, clamps late, or behaves inconsistently, making the fault harder to diagnose.

When is a Schottky clamp diode better than a Zener diode for overvoltage protection?

A Schottky clamp diode is usually the better choice when timing matters more than precision. It turns on quickly, limits fast voltage excursions, and protects sensitive nodes from brief spikes. This makes it suitable for logic pins, MOSFET gates, and analog inputs.

A Zener diode defines a more predictable clamp voltage but reacts more slowly and dissipates more energy once active. In many real designs, neither device is sufficient alone. A Schottky handles fast edges, while a Zener establishes the final ceiling. When surge energy increases further, both must give way to a TVS or higher-energy protection element.

How can I estimate conduction and leakage losses for a Schottky diode such as BAT46WJ in my design?

The calculation itself is simple; the challenge is knowing which term dominates. Conduction loss is roughly the forward voltage multiplied by average current. For a small-signal device like BAT46WJ, this is rarely critical unless the diode conducts continuously.

Leakage loss often appears later, during thermal testing. Leakage increases rapidly with temperature and can quietly inflate standby power. The practical approach is to calculate both losses and then validate them on the bench using real operating conditions rather than idealized datasheet points.

What layout mistakes commonly cause signal-diode applications to fail at high frequencies?

At high edge rates, placement dominates behavior. A Schottky used as a signal diode may be electrically correct but ineffective if it sits too far from the node it is meant to protect. Extra trace length adds inductance, delaying conduction and raising peak voltage.

Large pads and long loops increase parasitic capacitance, loading the signal and softening edges. Polarity errors make matters worse, because a reversed clamp may partially work and obscure the real issue. Designers who treat signal diodes like high-speed passives usually avoid these failures.

How do recent SiC Schottky diode developments affect design choices in automotive and EV systems?

SiC Schottky diodes have changed expectations at high voltage and high power. Their low switching loss and high reverse-voltage capability make them attractive in traction inverters, onboard chargers, and PFC stages.

At the board level, however, silicon Schottkys remain dominant. Small-signal protection, interface clamping, and auxiliary paths do not benefit from SiC’s voltage capability and cannot justify its size or cost. In practice, the two technologies coexist, each serving a clearly defined electrical role.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.