RP-SMA Connector Guide: Avoid Mismatch & Returns

Dec 22,2025

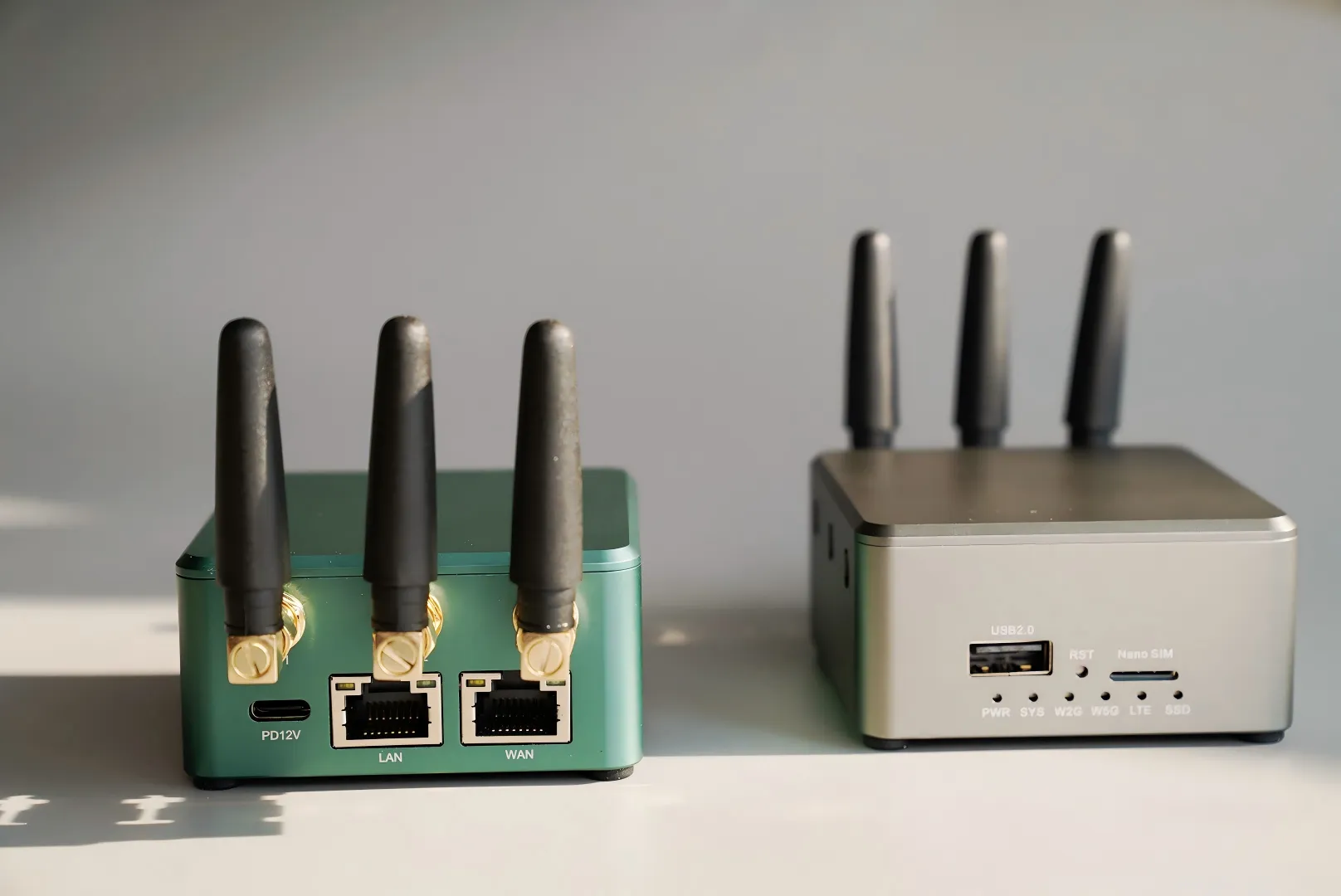

This figure is located at the beginning of the document as an introductory visual. It is likely a composite or scene image that vividly depicts the typical frustrating scenarios engineers or users face when installing, upgrading, or repairing equipment due to RP-SMA connector mismatches. For example, it might show a person trying to screw an antenna onto a router port but failing, or a desk scattered with connectors that look similar but have different polarities. Its purpose is to immediately resonate with the reader about the “RP-SMA puzzle” and introduce the identification, matching, and troubleshooting methods that will be explained step by step later.

Whether you’re wiring a Wi-Fi router, upgrading an IoT gateway, or repairing a bulkhead-mounted antenna, chances are you’ve run into the RP-SMA puzzle at least once. It looks simple—two threaded connectors that should fit—but one wrong detail can leave you twisting in frustration.

At TEJTE, our engineers see this problem weekly. Customers send back cables that “almost matched,” only to discover the pin and hole were reversed. The fix isn’t fancy equipment or calibration; it’s knowing how to read the connector by eye before you click “buy.”

This guide walks through that process step by step — identifying SMA vs RP-SMA connectors, matching antenna cables correctly, and avoiding common installation traps. You’ll also find a quick loss calculator, waterproofing tips, and a one-click order checklist used in TEJTE’s own assembly line.

If you’ve ever thought, “Why doesn’t this antenna fit my router?” — this article will finally make it make sense. Let’s start with the ten-second test every engineer should know.

Is My Port SMA or RP-SMA — How Can I Tell in 10 Seconds?

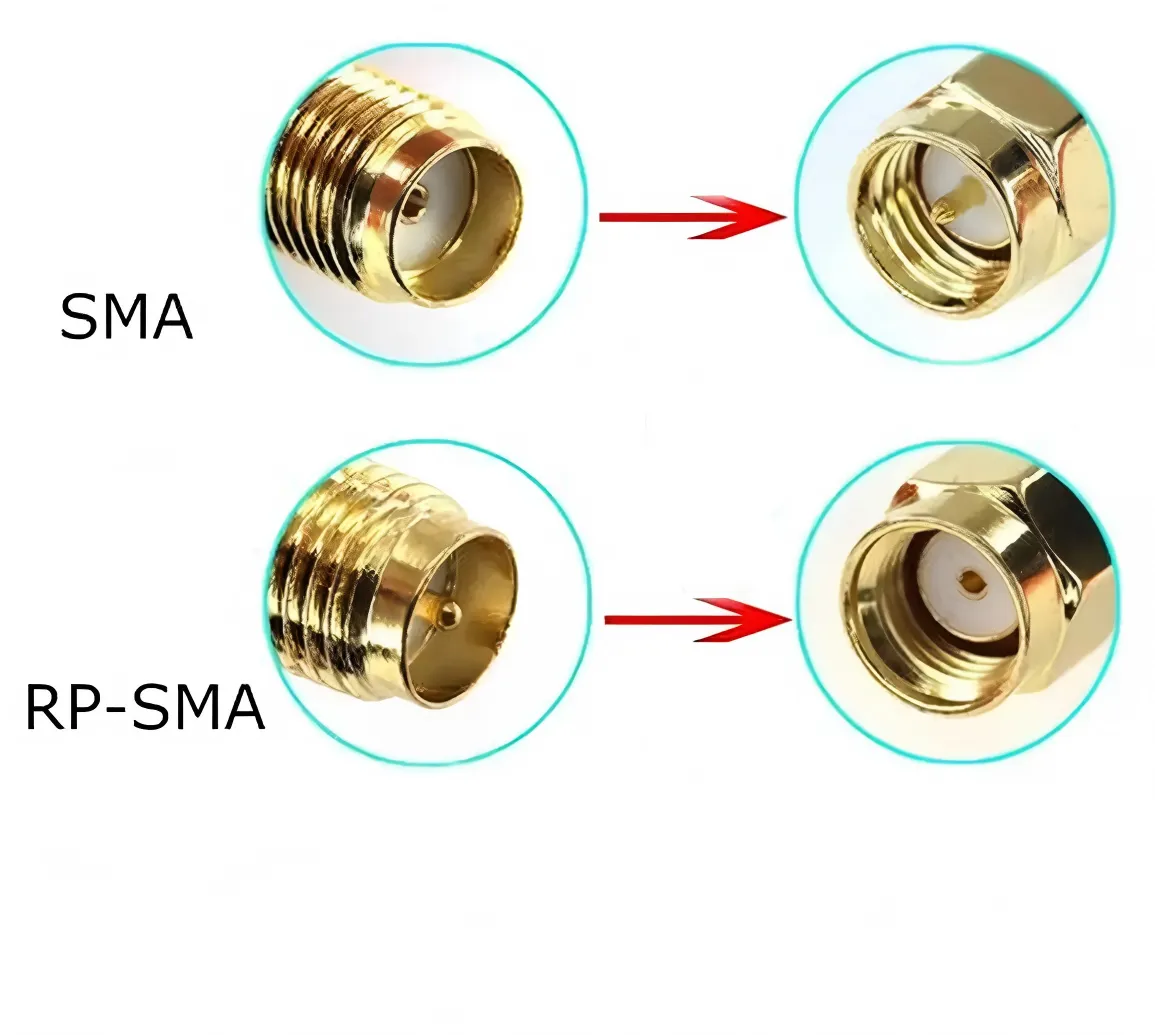

This figure is the key tool for answering the core question: “Is My Port SMA or RP-SMA — How Can I Tell in 10 Seconds?”. The figure likely arranges standard SMA and RP-SMA male and female connectors side by side or in close-up views. It uses clear arrows, circles, or highlights to mark the two decisive features: thread location (outer vs inner threads) and center conductor (pin vs hole). It is accompanied by concise text descriptions (e.g., “SMA Male: outer thread + pin”). This figure aims to translate complex terminology into intuitive visual inspection steps, allowing users to quickly and accurately identify connectors without tools or specialized knowledge, serving as the first line of defense against procurement errors.

If you’ve ever ordered an antenna online and it almost fits — you’re not alone. The difference between SMA and RP-SMA connectors looks trivial until you try to screw them together. That tiny mismatch is the reason so many returns happen in RF accessories.

Here’s a trick that engineers use on the bench. Forget the confusing “male” and “female” naming for a second — just look at two things:

- Does it have an outer thread or inner thread?

- Is there a pin or a hole in the middle?

Now decode it:

- SMA Male → outer thread + pin

- SMA Female → inner thread + hole

- RP-SMA Male → outer thread + hole (reverse)

- RP-SMA Female → inner thread + pin

Once you see it, you’ll never confuse them again. The “RP” literally means reverse polarity — the pin and hole are swapped.

Why do consumer routers still use RP-SMA? It’s a historical quirk. Years ago, U.S. regulators didn’t want people swapping antennas and breaking RF rules, so manufacturers switched to “reverse” connectors that weren’t compatible with professional SMA types. The rule eventually faded, but Wi-Fi hardware kept the design for consistency.

If you’re unsure, here’s a quick sanity check you can do right now:

- Router port = inner thread + pin → that’s RP-SMA female

- Antenna plug = outer thread + hole → that’s RP-SMA male

- Outer thread + pin? That’s standard SMA male — don’t force it.

Most listings online mix the labels. A seller might write “SMA-M” and show a picture of an RP-SMA part. Always trust the center contact, not the title. You can also cross-reference TEJTE’s Coaxial Cable Guide for mechanical specs — thread depth, dielectric type, and common misfits are all explained there.

One quick look saves hours of re-ordering and frustration. The pin never lies.

How Do I Match Antenna and Cable Ends — Male-to-Female or Male-to-Male?

This figure is located in the “How Do I Match Antenna and Cable Ends?” section. It is a connection schematic, typically using a common home Wi-Fi router system as an example. The figure clearly labels three key nodes: 1) Device Port (e.g., RP-SMA Female on the router backplate), 2) Extension Cable (with RP-SMA Male on one end and RP-SMA Female on the other), 3) External Antenna (RP-SMA Male). Arrows or lines are used to show the correct connection sequence (“male” to “female”) and polarity consistency among them. This figure aims to resolve users’ confusion about combining “male” and “female” connectors even after identifying the connector type. By visualizing the correct “chain,” it ensures both physical and electrical connectivity throughout the signal path are correct.

You’ve figured out the connector type. Great. Now comes the real puzzle: matching ends.

This is where people accidentally build “Frankenstein” cable chains that barely hold signal.

Let’s map the usual Wi-Fi setup first:

- Router or AP port: RP-SMA female (inner thread + pin)

- Antenna: RP-SMA male (outer thread + hole)

- Extension cable: RP-SMA male to RP-SMA female

That combination keeps polarity and gender consistent. It’s easy to remember: female at the device, male at the antenna. Now, if your device uses standard SMA instead, flip the logic. SMA-female on the board → SMA-male on the antenna.

This reversal is exactly what confuses first-time buyers.

A common mistake? Assuming a “male-to-female” SMA cable fits everything. Physically, it might screw in — but if the pin/hole polarity is off, you’ll have no contact at all. You might even think your antenna’s dead when it’s just mismatched.

Each extra adapter you stack adds about 0.2 dB of insertion loss. On paper, that sounds small, but at 5 GHz, every tenth of a decibel matters. Two adapters and an extension could cost you nearly a full dB — enough to cut your link margin.

When in doubt, draw it out:

Device → Cable → Antenna

Note “SMA” or “RP-SMA” and mark whether it’s male/female, pin/hole.

That sketch will instantly tell you if you need an adapter or if your setup already matches.

If you’re working on an IoT gateway or a test rig where cables chain through multiple adapters, consider the signal path length too. TEJTE’s Wi-Fi Antenna Cable Guide shows how connector count, cable type, and frequency stack together to affect real-world wifi antenna cable performance. Even a small mismatch adds return loss, which can creep up until your signal starts bouncing instead of transmitting.

Bottom line: fewer joints, shorter cables, better throughput. Your spectrum analyzer will thank you.

Bulkhead or Flange for Panel Mounting — How Do I Size the Thread?

Now let’s talk about mounting.

When your SMA or RP-SMA connector goes through a panel, you’ll have two main choices: bulkhead or flange-mount. Each fits a different mechanical philosophy.

This figure appears in the discussion on panel mounting selection. It is a comparative schematic that displays two mainstream panel mounting methods—Bulkhead and Flange—side by side. For the Bulkhead type, the figure might show a cross-sectional or exploded view of it passing through a panel hole, secured by a long threaded sleeve and an internal nut, possibly labeling components like “panel thickness,” “O-ring,” “washer,” and “nut.” For the Flange type, it shows how it is directly fixed to the panel via two or four screw holes, highlighting its features for vibration resistance and high-grade sealing. This figure helps users intuitively understand and choose the most suitable panel mounting solution based on enclosure thickness, sealing requirements (e.g., IP rating), and mechanical strength needs (e.g., vibration resistance).

Bulkhead connectors are the ones with a long threaded barrel and a nut on the other side. They’re compact, simple, and perfect for routers, modems, or sensor boxes. The key detail isn’t the connector type — it’s thread length.

You’re not just clamping metal to metal; you’re compressing a stack:

- Panel thickness

- O-ring or rubber gasket

- Lock washer

Let’s do some quick math.

If your panel is 1.2 mm thick, the O-ring adds 0.8 mm, and the washer adds 0.5 mm, you’ll need roughly 2.5 mm of usable thread just to secure it. Add a millimeter or two for safety. For thin enclosures (<2 mm), a 4 mm-thread bulkhead is fine. For thicker or double-layer panels, go with 6 mm.

This figure is specifically dedicated to showcasing the Flange connector product. It likely consists of two parts: on the left or top is a close-up product photo, clearly showing a typical 2-hole or 4-hole SMA/RP-SMA Flange connector, highlighting its robust housing, screw holes on the mounting ears, the interface threads, and possibly an attached sealing gasket. On the right or bottom is an installation schematic or cross-sectional view, demonstrating how the connector aligns with holes on the panel, is secured using screws, and achieves a seal against the panel, likely by compressing an O-ring or gasket. This figure visually communicates the core advantages of Flange connectors over Bulkhead types: stronger resistance to vibration and torque due to screw fixation, and more even sealing pressure, making them suitable for applications requiring high reliability and IP ratings, such as outdoor gateways, test equipment, or vehicular systems.

Flange connectors, on the other hand, use two or four screw holes to bolt directly to the case. They’re stronger and seal better under vibration. You’ll find them on outdoor gateways, RF test panels, or automotive gear. Two-hole flanges are small and handy; four-hole flanges handle weatherproof and high-torque applications.

Don’t rely on the threads for waterproofing. The seal happens at the O-ring compression, not the nut torque. For an IP67 setup, tighten until the rubber visibly compresses — roughly 0.6 N·m is enough. Go further and you risk bending the dielectric, which quietly wrecks VSWR even though the connector “looks fine.”

Need more field references? TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna Installation Guide shows real sealing stacks used in harsh conditions — great for understanding IP67 mounting and torque balancing in outdoor designs.

One last tip: check your panel cutout.

Most SMA bulkheads require a 6.4 mm hole. Some “mini bulkheads” use 6.0 mm, while heavy-duty versions might ask for 6.6 mm. Measure twice, drill once. Nothing feels worse than realizing your connectors spin freely because the hole’s 0.3 mm too wide.

How Long Can I Extend Before 5 GHz Range Drops?

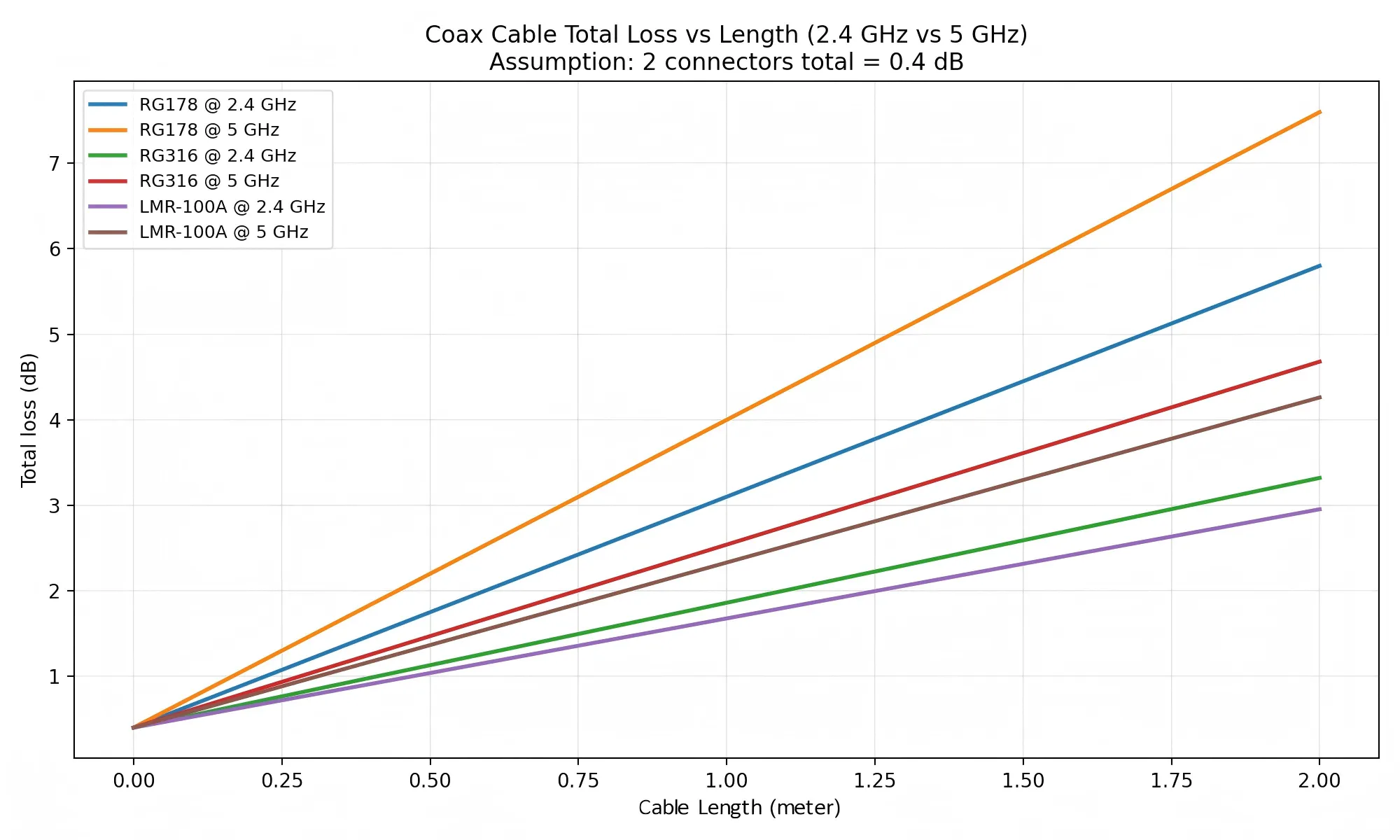

This figure is the technical basis for answering “How Long Can I Extend Before 5 GHz Range Drops?”. It is a professional two-dimensional line chart where the X-axis represents Cable Length (meters) and the Y-axis represents Total Loss (dB). The chart contains multiple colored lines, each representing the loss performance of a different cable model (e.g., RG178) at different frequencies (e.g., 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz). The chart clearly shows several key patterns: 1) For the same cable, loss increases with frequency (the 5 GHz line is above the 2.4 GHz line); 2) Thicker, higher-quality cables have lower loss (e.g., the RG316 line is below the RG178 line); 3) Loss increases linearly with length. This figure enables users to quantitatively assess the impact of increasing cable length on the system link budget, providing data support for decisions on whether to extend the cable and which cable type to choose.

RF engineers know this pain: you add a short SMA extension cable, and suddenly the 5 GHz link isn’t what it used to be.

At first glance, a half-meter lead looks harmless. But once frequency climbs, even small coaxial losses add up fast.

Let’s take a real example. A RG178 coaxial cable, common in router pigtails, loses about 0.6 dB per meter at 2.4 GHz and roughly 1.0 dB per meter at 5 GHz. Add two connectors (≈ 0.4 dB combined), and you’ve already spent more than a dB of your signal budget. That might sound small, but it can trim 10–15 % off your coverage distance.

At 2.4 GHz, you’ll hardly notice; at 5 GHz, it’s obvious.

So what’s “safe”?

Keep your total extension below 0.5 m whenever possible.

Beyond that, compensate with a slightly higher-gain antenna or lower-loss coax such as RG316 or LMR-100.

Longer doesn’t always mean worse — it depends on layout. If your cable sits near hot components or bends too tightly, loss increases further. Maintain at least a 10 × OD bend radius; for RG178 that’s around 18 mm. Sharp bends crush the dielectric and change impedance.

If you’re unsure about which cable grade to pick, TEJTE’s Coaxial Cable Guide lists typical attenuation curves across frequency bands and shows how small mechanical choices affect loss consistency.

Typical RG178 Loss and Bend-Radius Reference

| Frequency | Approx. Loss (dB / m) | Recommended Max Length | Minimum Bend Radius |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | 0.55 – 0.65 | ≤ 2 m | ≥ 18 mm |

| 5 GHz | 0.95 – 1.10 | ≤ 1 m | ≥ 18 mm |

| 6 GHz (Wi-Fi 7) | ≈ 1.25 | ≤ 0.8 m | ≥ 20 mm |

Do I Need Waterproofing — Cap Only or Full Sealing Stack?

If your device ever sits outdoors, or even near a humid wall, waterproofing your RP-SMA bulkhead isn’t optional. Many assume the metal thread keeps water out. It doesn’t.

The real barrier is the O-ring compression between the connector shoulder, washer, and panel face.

Here’s the correct order, inside-to-outside:

Cable → Connector → O-ring → Panel → Washer → Nut → Cap (optional)

That O-ring should compress about 15–20 % of its height — enough to seal, not enough to bulge. Use silicone grease sparingly to prevent sticking during future maintenance.

For IP67-grade sealing, you also need a waterproof cap when the port remains unused. TEJTE supplies rubber-lined SMA caps that maintain pressure and block condensation; details are covered in its Outdoor Omni Antenna Installation Guide. A cap alone won’t fix a loose bulkhead, but it’s the final layer that protects the threads.

Torque matters too. Most SMA bulkheads seal reliably at 0.6 – 0.8 N·m. Anything higher can distort the dielectric and slightly tilt the center pin. In lab measurements, even a 0.1 mm offset can shift return loss by > 1 dB. That’s why professional installers always use a small torque wrench, not just “finger tight.”

Outdoor / Humid Re-Torque Checklist

If you service gear in harsh environments, create a small routine check:

- Inspect O-ring for cracks or flattening.

- Clean metal threads with alcohol; avoid sand or oxide dust.

- Verify cap tightness after temperature swings (metal expands, seals relax).

- Re-torque lightly once a year or after seasonal humidity changes.

- Replace seals every 3–4 years — rubber ages faster than you think.

Many field failures blamed on “bad connectors” are actually leakage failures. Moisture creeps in, corrodes the inner contact, and the signal dies slowly over months. A $0.20 O-ring could have saved the entire link.

Mini-PCIe / M.2 Router Short Lead — What’s the Safe Extension Plan?

Modern mini-PCIe or M.2 Wi-Fi cards often use U.FL or IPEX micro-connectors that jump to an RP-SMA bulkhead on the chassis. Extending these leads looks tempting, but it’s easy to overdo.

Keep the U.FL to SMA pigtail as short as possible (10–15 cm typ.). Beyond that, signal reflections rise steeply because of the impedance transition from 50 Ω micro-coax to SMA bulkhead.

If you must extend further, do it after the bulkhead with a standard RP-SMA extension cable, not before. That keeps the fragile U.FL end untouched inside the enclosure. For tight builds, use low-loss coax rated for 5–6 GHz — LMR-100 or RG316 are good candidates.

For dual-band routers, expect around 0.8 dB loss per 0.5 m at 5 GHz. That’s fine indoors. Just avoid chaining multiple pigtails; each adapter adds loss, mismatch, and physical strain.

When planning your extension, revisit the Loss Estimator above and keep total loss under 1 dB if possible. It’s the sweet spot between convenience and performance.

Do Wi-Fi 7 and 6 GHz Rules Change Connector or Cable Choices?

Yes — but indirectly. The connectors themselves haven’t changed, yet the frequency range they carry has. Wi-Fi 7 (802.11 be) operates deeper into the 6 GHz band, which means insertion-loss tolerance tightens.

The U.S. Federal Register opened the entire 5.925 – 7.125 GHz range to Very Low Power (VLP) indoor devices, expanding what used to be partial access. For outdoor and enterprise links, standard-power 6 GHz operation now depends on Automated Frequency Coordination (AFC) databases — tested in early pilots by Cisco and Federated Wireless.

What does that mean for hardware?

- Keep total cable loss < 1.2 dB between radio and antenna.

- Prefer short RG316 or LMR-100 pigtails.

- Maintain connector VSWR ≤ 1.3 : 1 up to 7 GHz.

As deployment scales, enterprises start favoring IP67 bulkhead connectors to ensure outdoor compliance. You’ll find detailed sealing practices in TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna Guide.

While the connector series stays the same, the new spectrum leaves less room for sloppy cabling. A 1 dB error at 2.4 GHz is mild; at 6 GHz, it can mean certification failure.

Final Word

This figure is located in the “Final Word” section of the document. It is a summary infographic or schematic aimed at reinforcing the core recommendations of the entire guide. The figure might use icons, brief text, and arrows to visually summarize several key action points, for example: a magnifying glass pointing to the center of a connector (emphasizing observe the center pin/hole), calipers measuring panel thickness (emphasizing accurate measurement), a diagram of several connectors in series with a number annotation (emphasizing reduce connector count to lower loss), and possibly a flowchart or checklist icon representing “planning.” Its function is to provide a concise, memorable visual checklist after the user has read all the details, solidifying good engineering practice habits to ensure reliable future RF setups free from troubleshooting.

Choosing between SMA and RP-SMA is less about guessing and more about observation and planning.

Look for the pin. Measure your panel. Count your connectors.

Those habits separate reliable RF setups from endless troubleshooting.

If this article saved you from another mismatched order, you’ll probably enjoy the in-depth breakdowns in TEJTE’s Wi-Fi Antenna Cable Guide and Coaxial Cable Guide.Both expand on the same principles of loss budgeting and physical compatibility — essential knowledge for anyone wiring up Wi-Fi 6/7 or IoT hardware.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

1. How can I tell RP-SMA from SMA without opening the device?

Look at the center contact. If the router port has a pin, it’s RP-SMA female. If it has a hole, it’s SMA female. The thread direction doesn’t change — only the pin polarity.

2. Will a 0.5 m RP-SMA extension reduce 5 GHz throughput?

Slightly — expect about 0.9 dB loss for RG178 at that length. That equals roughly 10–15 % less range. Keep it under 0.3 m if possible.

3. What bulkhead thread length fits a 1.5 mm aluminum panel with a gasket?

Add up the stack: 1.5 mm panel + 0.8 mm gasket + 0.5 mm washer ≈ 2.8 mm. Choose a 4 mm thread connector for reliable compression and seal.

4.Can I mix an RP-SMA antenna with an SMA bulkhead using an adapter?

Physically yes, electrically risky. Adapters add 0.2–0.3 dB loss each and slightly distort VSWR. Use only when no other option.

5.Do Wi-Fi 7 and 6 GHz rules change the connector series I should use?

No new mechanical series — still SMA / RP-SMA — but specs are stricter. Target VSWR ≤ 1.3 : 1 and use low-loss coax under 1 m.

6. How can I avoid ordering the wrong RP-SMA cable type online?

Double-check polarity (pin / hole) and mount type (bulkhead / flange) before purchase. Use the Order Checklist above — copy it into your supplier notes to guarantee fit. TEJTE includes this step in all shipment inspections.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.