RG316 Coax Cable Guide for RF Modules & Test

Feb 13,2026

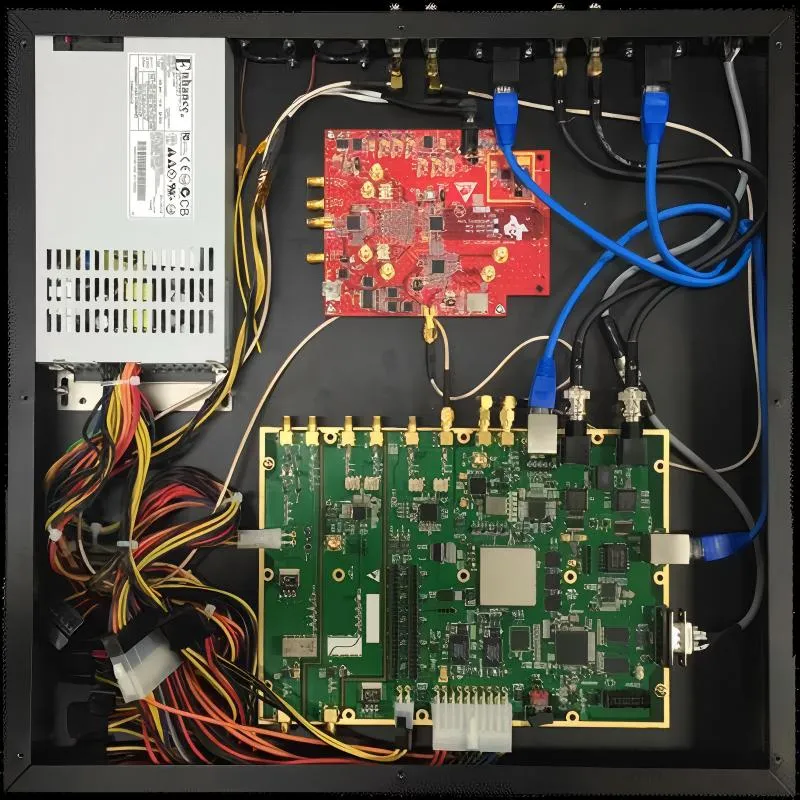

This introductory figure presents a standard RG316 coaxial cable assembly. The surrounding text establishes the guide's core premise: in RF hardware, cables are rarely blamed first, yet treating them as "passive background" is risky. RG316 occupies a specific niche—it is thin enough for dense enclosures, thermally stable due to PTFE dielectric, and flexible enough for repeated handling. The image visually anchors the discussion that follows, framing RG316 as an engineering choice rather than a casual catalog selection.

In RF hardware, cables rarely get blamed first. When a link loses margin or measurements drift, attention usually goes to active devices, antenna tuning, or layout tweaks. The coaxial cable connecting everything tends to be treated as passive background—something that either works or doesn’t.

That assumption is risky.

RG316 coax cable sits in a narrow but important niche. It’s thin enough to fit into dense enclosures, stable enough to survive high temperatures, and flexible enough for repeated handling. At the same time, it is often pushed close to its limits—used as internal jumpers, test leads, or short antenna feeds where small losses and mismatches actually matter.

This guide approaches RG316 coax cable as an engineering choice, not a catalog item. The goal is to help you decide when it makes sense, how to read its specs in practical terms, and where it fits relative to other small RG cables and common SMA cable assemblies used in RF modules and lab setups.

Clarify when RG316 coax cable is the right choice for your RF link

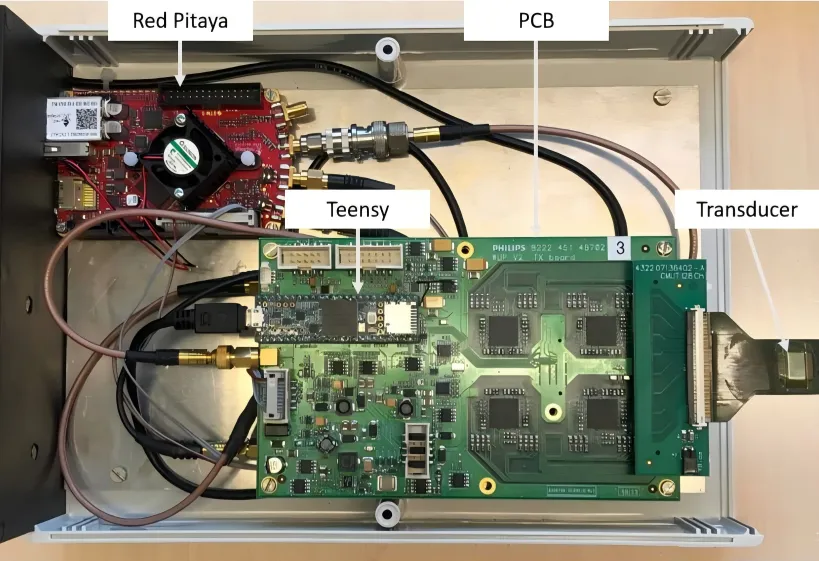

This figure, appearing in the section "Clarify when RG316 coax cable is the right choice," visually explains the cable's purpose. It contrasts RG316 with larger low-loss cables, showing that RG316 was never meant to compete on attenuation. Instead, its value lies in solving a different problem: providing reliable RF interconnects in environments where space is tight and thermal demands are high. The image helps engineers internalize that RG316 is often chosen despite its loss, not because of it.

Compare RG316 coax cable with other small RG cables in real projects

RG316 is often mentioned alongside RG174 and RG178, but real hardware quickly exposes their differences.

RG174 is popular because it’s inexpensive and easy to source. The downside shows up once temperatures rise or cables are reworked. Its polyethylene dielectric softens long before many RF modules reach their upper operating limits. Engineers who have debugged drifting impedance after enclosure heat soak usually learn this the hard way.

RG178 sits at the opposite extreme. It is thinner and also PTFE-based, which makes it attractive for ultra-compact layouts. In practice, its mechanical robustness is limited. Shields deform easily, and connector transitions become fragile unless strain relief is excellent.

RG316 coax cable lands between these two. Its PTFE dielectric gives it thermal stability similar to RG178, while its larger diameter and heavier braid tolerate handling, re-bending, and connector torque better. That balance is why RG316 shows up repeatedly in RF modules that must be serviced or tested more than once.

Map typical RG316 coax cable use cases in modules, jumpers, and test leads

This figure maps the three most common real-world applications for RG316 coax cable: internal RF module jumpers (board-to-board or module-to-panel), short test patch cords (SMA cable assemblies between instruments and DUTs), and adapter leads (MMCX or MCX cable assemblies transitioning to SMA interfaces). The surrounding text emphasizes that in these scenarios, the cable is rarely long—what matters is consistency. A jumper that behaves the same after the tenth reconnection as it did on day one saves time during debugging and validation. The image makes these distinct roles visually clear.

Most real-world uses of RG316 coax cable fall into three categories:

- Internal RF module jumpers, where board-to-board or module-to-panel links must bend around mechanical features

- Test patch cords, especially short SMA coax cable assemblies used between instruments and DUTs

- Adapter leads, such as MMCX cable or MCX cable assemblies transitioning from compact connectors to SMA interfaces

In these scenarios, the cable is rarely long. What matters more is consistency. A jumper that behaves the same after the tenth reconnection as it did on day one saves time during debugging and validation.

This is also why RG316 frequently appears in systems discussed in broader RF cable overviews, such as the internal wiring examples covered in RG cable guide. It’s not because RG316 is exotic—it’s because it reliably fills a gap other small cables struggle with.

Decide when RG316 is better than larger cables like RG58 or RG223

A common mistake is assuming RG316 can simply replace thicker 50-ohm cables everywhere. It can’t—and shouldn’t.

Larger cables like RG58 or RG223 win decisively on attenuation, especially as frequency and length increase. If your RF path runs several meters or operates near the top end of your band, RG316’s higher loss becomes difficult to ignore.

Where RG316 coax cable makes sense is when mechanical and spatial constraints dominate. Inside compact enclosures, behind front panels, or between closely packed modules, thicker cables introduce routing stress and assembly variability that often outweigh their lower loss.

In short, RG316 is usually chosen despite its loss, not because of it. The key is knowing when that compromise is acceptable.

How should you interpret RG316 coax cable specs for real hardware?

Read RG316 coaxial cable construction: conductor, dielectric, braid, jacket

A typical RG316 coaxial cable uses a silver-plated copper center conductor surrounded by a PTFE dielectric. This combination keeps resistance low at RF frequencies and maintains impedance across a wide temperature range.

The shielding is usually a silver-plated copper braid. Compared with single-braid designs found in cheaper cables, this provides more stable shielding effectiveness when the cable is flexed or routed near other harnesses.

The outer jacket is commonly FEP or PTFE. This is one of the reasons RG316 survives solder rework, hot enclosures, and repeated lab use better than PVC- or PE-jacketed options. The trade-off is slightly higher stiffness, which must be managed with proper bend radius and strain relief.

Translate key RG316 coaxial cable ratings into design limits

Several RG316 specs matter far more in practice than others:

- Impedance (50 ohms) defines how sensitive the cable is to connector geometry and termination quality

- Frequency range sets expectations, but attenuation—not cutoff—is what usually limits usable length

- Temperature rating determines whether loss and impedance stay stable over operating life

- Voltage rating is rarely limiting in RF modules, but can matter in test environments

What often gets overlooked is how these limits interact. A cable operating well within its frequency rating can still introduce unacceptable mismatch if connectors are poorly installed or the dielectric is damaged during stripping.

Connect RG316 coax cable specs back to SMA and MMCX assemblies

Once connectors are attached, you no longer have “just” RG316 coax cable. You have an RF assembly whose performance depends on how well the cable and connector geometries align.

This is especially relevant when RG316 is used in SMA cable or MMCX cable jumpers, where small tolerances dominate return loss. Many issues blamed on the cable itself turn out to be termination problems—something explored in more depth in related connector-focused guides like SMA coaxial cable structure and selection.

Plan RG316 coax cable length and loss for different frequencies

Estimate insertion loss for RG316 coaxial cable across common RF bands

| Frequency | Typical RG316 Loss (dB/m) | Practical Insight |

|---|---|---|

| 433 MHz | ~0.3 dB/m | Often negligible in short internal runs |

| 900 MHz | ~0.5 dB/m | Still forgiving for module-level links |

| 2.4 GHz | ~0.9 dB/m | Loss becomes visible in tight budgets |

| 5.8 GHz | ~1.4–1.6 dB/m | Length must be planned deliberately |

At higher frequencies, connector losses and impedance discontinuities can rival the cable loss itself. This is why “same-length” SMA RF cable jumpers sometimes measure differently once assembled by different vendors.

If you need a refresher on how attenuation scales with frequency in coaxial structures in general, the explanation of loss mechanisms in the coaxial cable overview provides useful background without being vendor-specific.

Balance RG316 cable length against link margin and system budget

A more useful question than “How long can RG316 run?” is “How much loss can my system tolerate?”

In RF modules, available link margin is often smaller than expected. Filters, switches, matching networks, and connectors all consume margin before the cable is even considered. When RG316 coax cable is added late, it becomes an easy scapegoat for problems that were really budget issues from the start.

For short test setups, margin is usually generous. For embedded products, especially battery-powered or low-power radios, every decibel matters. This is why RG316 works well in lab SMA cable jumpers but must be re-evaluated when moved into a product enclosure.

Acceptable margin expectations across common frequency bands

In practice, many RF teams converge on similar thresholds:

- ≥ 6 dB remaining margin

Comfortable. Cable choice is unlikely to dominate system behavior.

- 3–6 dB

Review required. Assembly quality, routing, and connector selection matter.

- < 3 dB

Redesign territory. Shorten the run, reduce connector count, or move to a lower-loss cable.

As frequency increases, the usable length of RG316 shrinks faster than most engineers expect. What feels trivial at sub-GHz becomes meaningful at 2.4 GHz, and restrictive at 5 GHz.

Convert lab patch-cord lengths into field-deployable RG316 assemblies

A common transition looks like this: a 30 cm RG316 SMA coax cable works perfectly on the bench. The same cable, once routed internally with two extra connectors and a tighter bend radius, suddenly shows higher VSWR or reduced sensitivity.

Nothing “mystical” happened. The environment changed.

When migrating from lab to product, always re-evaluate:

- Total connector count

- Actual routing length, not straight-line distance

- Bend severity near connectors

- Proximity to noisy harnesses

This discipline mirrors the system-level thinking recommended in broader RF interconnect discussions, such as those found in the SMA coaxial cable structure and selection guide.

Match RG316 coax cable with SMA, MMCX, MCX, and BNC interfaces safely

RG316 coax cable is commonly terminated with:

- SMA connectors for test equipment and antenna feeds

- MMCX or MCX connectors for compact RF modules

- BNC connectors in mixed RF or legacy measurement setups

Each interface imposes different mechanical and electrical stresses. SMA handles torque well but punishes over-tightening. MMCX tolerates rotation but dislikes side load. MCX sits somewhere in between.

Understanding these behaviors helps when designing transitions such as MMCX-to-SMA jumpers built on RG316, which are discussed in more connector-focused contexts like MMCX cable guide for RF modules and SMA transitions.

Avoid impedance and geometry traps when crimping or soldering RG316 cable

RG316’s PTFE dielectric is forgiving thermally, but unforgiving mechanically. Small errors compound quickly:

- Over-stripping exposes shield and alters impedance

- Under-crimping increases contact resistance

- Distorted braid paths create localized mismatch

Many assemblies pass continuity tests yet fail return-loss checks. This is why RF inspection, even at a basic level, is more valuable than visual inspection alone.

Design RG316-based MMCX and SMA jumpers for repeatable builds

For repeatable production, variation must be engineered out:

- Fixed strip dimensions

- Calibrated crimp tools

- Documented torque limits

Teams that standardize these details early spend far less time chasing “random” RF issues later.

How can you route and bundle RG316 coax cable to avoid interference?

Separate RG316 coax cable from noisy digital harnesses in compact enclosures

Despite good shielding, RG316 coax cable is not immune to coupling from fast digital edges or switching regulators. Parallel routing over even short distances can inject measurable noise.

Physical separation is the most reliable mitigation. Where separation is impossible, controlled grounding and orthogonal crossings reduce coupling more effectively than adding ferrites after the fact.

Control bend radius and strain relief for long-term reliability

A practical minimum bend radius for RG316 is several times its outer diameter. Tighter bends concentrate stress at the connector interface, where failures tend to appear first.

Repeated flexing near the termination is especially damaging. Strain relief is not optional—it’s part of the RF design.

Use RG316 cable ties, labels, and routing patterns for service-friendly designs

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.