RG316 Cable Internal Routing & High-Temperature Reliability

Jan 9,2025

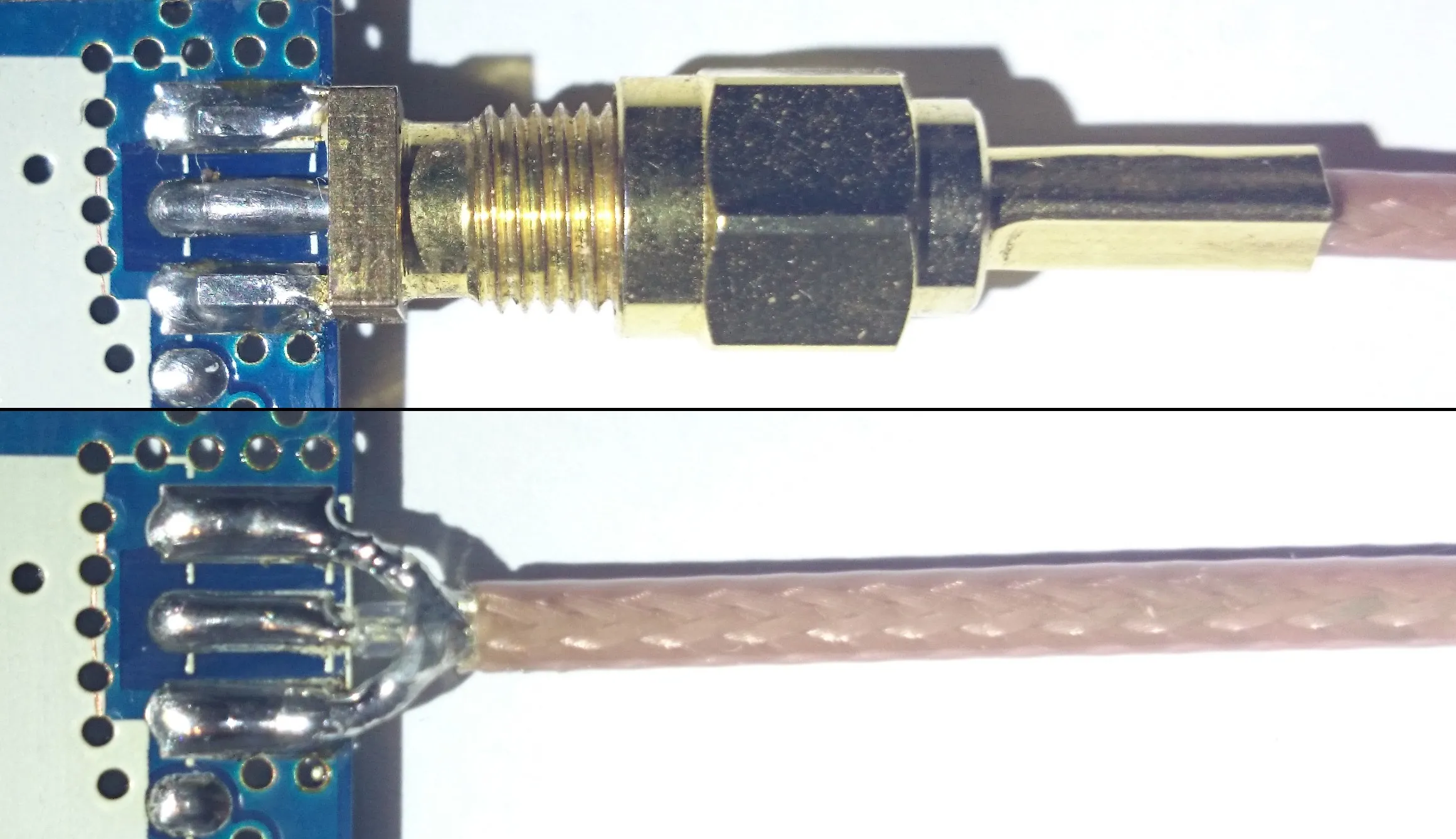

This image typically shows a schematic or cross-sectional view of an RG316 cable snaking through the interior of a typical electronics chassis (e.g., router, gateway). It likely depicts the cable connecting an RF module on a PCB to a bulkhead connector on the chassis panel, navigating through constrained spaces and near potential heat sources (e.g., heat sinks). This image aims to visualize the article’s core focus—how RG316 cable “fits” and is reliably routed within the “already locked” compact, high-temperature environment—and implies that it often passively absorbs unintended stresses like design tolerances and vibration, leading to later “gradual RF instability” rather than immediate failure.

In most hardware projects, RG316 cable is not selected because it is optimal. It is selected because it fits. The enclosure is already constrained, the RF path is already defined, and something flexible is needed to connect two fixed points. RG316 is thin enough, heat resistant enough, and familiar enough, so it gets used.

Internally, that short cable ends up doing more work than intended. It absorbs misalignment between PCB and panel. It takes up assembly tolerance. It sees vibration that was never assigned to it on the drawing. None of this is obvious during bring-up. Problems appear later, usually as gradual RF instability rather than a clean failure.

Length loss and link budget behavior are addressed elsewhere and are not repeated here. For attenuation-driven decisions, see RG316 coax cable jumpers: length and loss planning. This text focuses only on routing, temperature, and mechanical survival inside the enclosure.

Where does RG316 cable make the most sense inside real products?

Map typical internal use cases for RG316 cable in IoT, industrial, and telecom devices

This diagram, likely in a panel or composite schematic format, depicts typical “short internal runs” for RG316 cable in real products. Specific scenarios may include: 1) a bridging jumper between an RF module on a PCB and a panel connector on the chassis; 2) an RF jumper between two boards where alignment is imperfect; 3) a short link between different shielded sections inside a device. The image may be accompanied by simple device outlines (with labels like “TEJIATE”, “TEDDATE” hinting at device types). This diagram aims to answer the question “Where does RG316 cable make the most sense inside real products?” It emphasizes that its applications are driven by geometry and temperature, not by pursuing long-distance RF efficiency, and it is often used in survival scenarios where space is tight and temperature is elevated.

Across IoT gateways, industrial controllers, and telecom equipment, RG316 cable usually appears in short internal runs. PCB RF module to panel connector. Board-to-board RF jumpers where alignment is imperfect. Short links between shielded sections. In test fixtures, the same cable shows up because it tolerates heat better than soft-jacket micro-coax.

These applications are driven by geometry, not frequency. RG316 is chosen because thicker coax will not route through the space and because PVC-based alternatives degrade near heat sources. It is rarely selected for long RF paths. It is selected to survive where space is tight and temperature is elevated.

Decide when rg316 coaxial cable is “good enough” vs when a heavier coax family is safer

This is likely a horizontally arranged chart or a set of side-by-side cable cross-section/physical photos comparing various RG series cables including RG174, RG316, RG58, RG405, RG402, RG142. The image may annotate their outer diameters, colors (e.g., RG316 has a white variant), or key characteristics. This diagram is used to visually illustrate RG316’s position within the cable spectrum—more heat-resistant/robust than RG174, but thinner and more flexible than “heavier” cables like RG58, LMR. It supports a key argument in the text: RG316 works reliably only within a narrow envelope of short length, limited mechanical load, and controlled routing; once conditions deteriorate (e.g., continuous vibration, increased length), heavier cable families (e.g., RG58, LMR) degrade more slowly. RG316’s failure mode is “drift,” not abrupt breakage.

rg316 coaxial cable works reliably only within a narrow envelope. Short length. Limited mechanical load. Controlled routing. When any of those conditions drift, failures become more likely.

Once internal runs extend, or vibration becomes continuous, or the cable is expected to carry any structural load, heavier coax families degrade more slowly. RG58 and LMR cables are harder to route but tolerate abuse better. RG316 does not fail abruptly. It drifts. That drift is difficult to diagnose after deployment.

Engineers comparing these families across applications usually start from the broader context in the RG Cable Guide and then narrow down based on enclosure constraints.

Use rg316 coax cable as the last short run between PCB modules and panel connectors

One pattern holds up repeatedly. rg316 coax cable is most reliable when it is used only as the final flexible segment. The PCB is fixed. The enclosure connector is fixed. RG316 bridges the misalignment.

This prevents stress from transferring into PCB pads and solder joints. When degradation occurs, it remains confined to a replaceable cable assembly. Many failures attributed to “bad connectors” originate from stress passing through a cable that should never have carried it.

How should you plan RG316 cable routing and bend limits in CAD?

Translate enclosure CAD into realistic RG316 cable routes and keep-out zones

CAD routing for RG316 almost always looks better than reality. Curves are smooth. Clearances are exact. Installation is not modeled. Hands, tools, and cable stiffness are missing.

Routing should be treated as intent. Keep-out zones near fasteners and sharp edges matter more than symmetry. Extra length is not waste. Paths that only work when the cable is pre-shaped accumulate stress before the unit ever powers on.

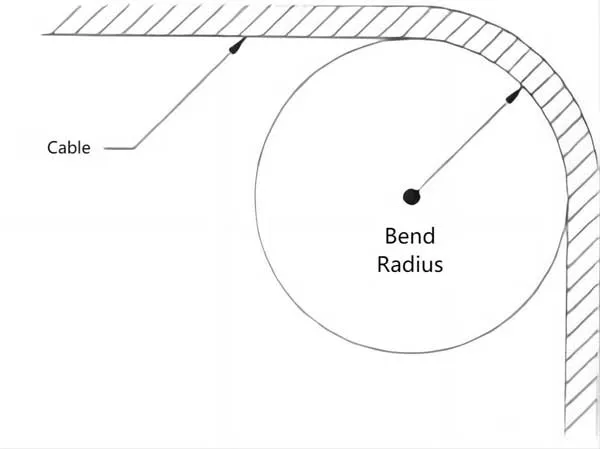

Choose practical minimum bend radii based on harness standards (6–10× OD rules)

This image consists of two parts: On the left is a clean schematic showing a cable segment bending around an arc, clearly labeling the definition of Bend Radius (typically the distance from the arc’s center to the cable’s centerline). On the right or below, there might be a calculation formula or numerical example, calculating that for RG316 (OD ~2.5mm), the lower boundary for minimum bend radius is around 15mm (6x OD), while for robust designs expected to survive vibration and rework, it’s recommended to be closer to 20-25mm (8-10x OD). This diagram applies the general guidelines from the harness industry specifically to RG316, emphasizing that bends tighter than this do not cause immediate visible damage but accumulate internal strain, leading to long-term impedance stability drift and difficult-to-trace failures.

Harness standards converge on the same guidance: minimum bend radius between six and ten times cable outer diameter. For RG316 cable, with an outer diameter near 2.5 mm, this places the lower boundary around 15 mm. Designs expected to survive vibration and rework typically push closer to 20–25 mm.

Bending tighter than this does not show immediate damage. PTFE does not crease. The jacket remains intact. Internal strain accumulates. After thermal cycling, impedance stability begins to drift. These failures are slow and rarely traced back to routing.

If a bend already looks aggressive in CAD, it will be worse once assembled.

Avoid “impossible to assemble” paths that look perfect in 3D but ignore technician hands

This schematic uses an exaggerated or typical scenario to show a routing path for an RG316 cable inside an equipment chassis. The path itself might appear smooth and elegant in the 3D model, but the image highlights how it ignores practical assembly feasibility: e.g., the connectors need to be installed in a specific order for the cable to pass through a narrow hole; or a bend in the path requires “twisting” the cable after one end is already fixed. The diagram might use dashed lines, arrows, or shaded areas to indicate the ignored space needed for “technician hands and tools.” This image serves as a warning: if the RG316 cable must be forced into position during assembly, the routing assumption is wrong. This introduces variability, uneven stress, and ultimately leads to early failure.

Some failures have nothing to do with RF. They come from assembly. Cable paths that only work if connectors are installed in a specific order, or bends that require twisting the cable during installation, introduce variability. Variability becomes uneven stress. Uneven stress becomes early failure.

If RG316 must be forced into position, the routing assumption is wrong.

RG316 Routing Risk Matrix

To make routing risk visible during design review, a simple RG316 routing risk matrix is often sufficient.

Inputs typically include segment length, minimum bend radius, cable outer diameter (≈2.5 mm), ambient temperature class, vibration level, and number of connector pairs. Bend ratio is calculated as min_bend_radius / (6 × cable_od). Tighter bends, higher temperatures, stronger vibration, and more connectors increase the score.

Low scores indicate routing that is unlikely to cause reliability issues. Medium scores suggest improving bend radius or adding strain relief. High scores usually justify rerouting or switching to a mechanically stronger cable family such as RG58 or LMR. The matrix does not replace judgment. It forces the conversation to happen early.

How can you keep RG316 cable reliable in hot, chemically harsh spaces?

Understand FEP jacket temperature and chemical limits for RG316 cable

RG316 cable is usually labeled as a high-temperature coax, and materially that is true. PTFE dielectric and FEP outer jacket tolerate temperatures far beyond what PVC or PE jackets survive. Many datasheets quote ratings approaching 200 °C.

That number is a material ceiling, not a comfortable operating point. Running RG316 near that limit continuously accelerates aging in ways that are not visually obvious. The jacket may look unchanged while dielectric properties slowly shift. In equipment expected to operate for years, many teams implicitly derate RG316 and try to keep continuous exposure closer to the 125–150 °C range.

Another issue is temperature uniformity. Internal thermal models usually describe average enclosure temperature. RG316 rarely lives in average conditions. It passes through localized hot zones, often created by components that cycle on and off. These local gradients matter more than the headline temperature rating.

Route rg316 cable away from MOSFET hot zones, regulators, and braking resistors

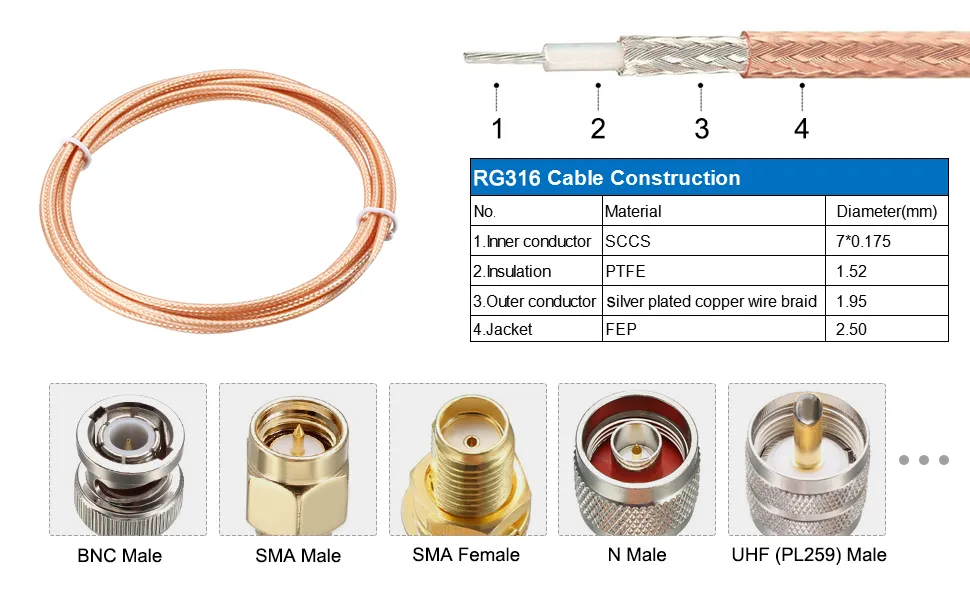

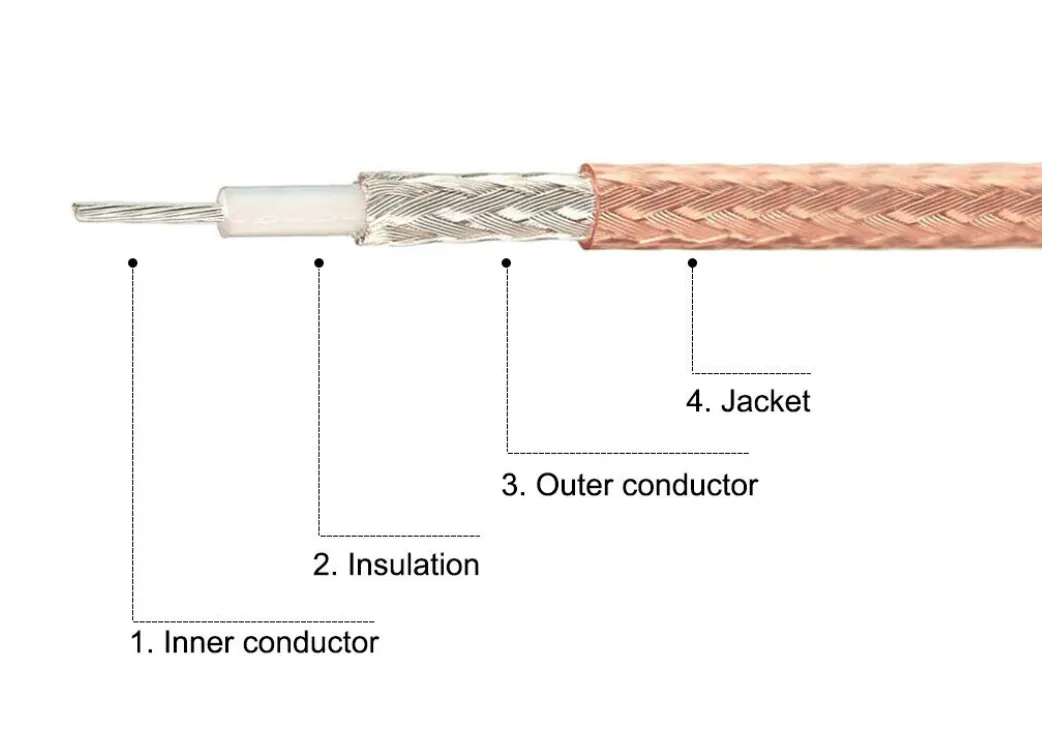

This image adopts a left-text-right-image or top-bottom combined layout. On the left or top is a clear table detailing the four-layer structure of RG316 cable: 1) Inner Conductor (material e.g., SCCS, diameter), 2) Insulation/Dielectric (PTFE), 3) Outer Conductor (Silver-plated copper braid), 4) Jacket (FEP), possibly including diameter data for each layer. On the right or bottom, physical images or icons of common connector types for RG316 cable assemblies are displayed, such as BNC Male, SMA Male, SMA Female, N Male, UHF (PL259) Male. This diagram links the cable’s intrinsic construction to its external interface flexibility, explaining both the physical origin of its high-temperature tolerance and flexibility, and its ability to adapt to various device ports through different connectors. It also provides the structural knowledge base for the subsequent discussion on keeping cables away from heat zones like MOSFETs.

Most heat-related failures involving rg316 cable come from proximity rather than ambient temperature. Power MOSFETs, linear regulators, braking resistors, and DC-DC converters create small but intense hot regions. Routing RG316 directly across these areas concentrates thermal stress into short cable sections and, more critically, into connector terminations.

Even small changes help. Shifting the cable a few millimeters away from a heat source can reduce radiant heating significantly. In tight layouts, a slightly longer route is usually safer than hugging a hot component. When designers later investigate degraded RF performance, these proximity decisions are often invisible in the schematic but obvious in the physical layout.

Handle oils, coolants, and cleaning chemicals that can slowly attack cable jackets

FEP resists many chemicals, but resistance is not immunity. In industrial and automotive environments, RG316 cable may be exposed to oils, coolants, flux residues, or cleaning agents over long periods. These substances rarely cause immediate damage. Instead, they soften the jacket or reduce its abrasion resistance.

The failure pattern is gradual. The cable survives until vibration or handling exploits a weakened area. Where chemical exposure is expected, routing should avoid low points where fluids collect and fixation points where chemicals remain in contact with the jacket. In some systems, adding a secondary sleeve or moving the cable slightly is more effective than switching cable type.

How do you control vibration and motion so RG316 cable survives?

Secure RG316 cable in vehicles, industrial machines, and compact test fixtures

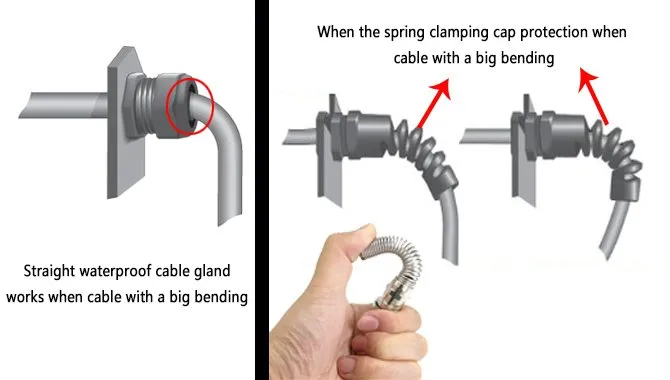

This schematic shows two cable fixation/protection solutions for vibration-prone environments. The first solution: Spring clamping cap protection, used when the cable is subject to big bending; it likely uses elastic elements to absorb vibration energy and prevent excessive movement at the bend point. The second solution: Straight waterproof cable gland, also used for cables with big bending; it provides a robust, sealed through-panel fixation point to eliminate micro-motion and stress concentration at the cable root. Arrows or annotations in the image may explain their working principles. This diagram supports the discussion in the text on securing RG316 cable in vibrating environments like vehicles and industrial machinery, emphasizing that effective control is mechanical, involving minimizing unsupported spans and using appropriate clamps, grommets, or tie mounts to limit oscillation without crushing the PTFE dielectric.

Vibration does not usually break RG316 cable outright. It works on it over time. The most common damage appears near connectors and fixation points, where the shield experiences repeated micro-bending. Long unsupported spans amplify motion and increase fatigue rate.

Effective control is mostly mechanical. Unsupported lengths should be minimized. Fixation points should limit oscillation without locking the cable rigidly in place. Hard anchoring immediately at the connector tends to concentrate stress where the cable is least tolerant.

Use clamps, grommets, and tie mounts without crushing the PTFE dielectric

Over-constraining RG316 causes its own problems. PTFE dielectric tolerates heat but does not recover from localized compression. Narrow clamps, sharp-edged mounts, or tightly cinched ties can deform the cable enough to alter impedance locally.

Good fixation spreads pressure. Wide clamps, soft grommets, and tie mounts that allow slight slip reduce stress concentration. Zip ties should locate the cable, not carry load. If the cable is structurally restrained by a tie, the design assumption is already wrong.

Plan for flex cycles and connector retention in moving joints and hinged panels

When RG316 cable passes through hinged panels or moving joints, static bend rules no longer apply. Flex life becomes the limiting factor. The bend radius must be increased significantly, and the flex zone must be controlled.

Random bending is far more damaging than controlled bending. Cables should flex in one plane, at one location, with sufficient radius. Connector retention also matters. Micro-motion at the connector interface accelerates loosening and shield damage. In these cases, strain relief near the connector is not optional.

Focus on RG316 cable construction details that actually affect reliability

Inner conductor: silver-plated CCS or copper, and what changes in real use

Not all RG316 cable is built the same. Inner conductors may be silver-plated copper-clad steel or silver-plated copper. Electrically, both perform well at RF. Mechanically, they behave differently.

Stiffer cores transmit more stress to terminations under vibration and bending. Softer copper cores tolerate motion better but stretch more under load. In static applications the difference is minor. In vibrating or flexing environments, it becomes noticeable. Neither option is universally better. The surrounding mechanical context determines which failure mode appears first.

PTFE dielectric, braid coverage, and FEP sheath—how each layer fails in the field

This is an extension or variant of the structural diagram in Figure 4 or Figure 6, but with a greater focus on field failure mechanisms. It likely uses a vertically arranged exploded view, showing the four layers of RG316 from top to bottom or with arrow indicators: 1) Inner Conductor, 2) Insulation/Dielectric (PTFE), 3) Outer Conductor (Braid Shield), 4) Jacket (FEP). Beside each layer, there might be brief text explaining its primary function and how failure can initiate under stresses like overheating, excessive bending, vibration, or chemical exposure (e.g., excessive bending stresses the dielectric; vibration fatigues the braid; chemical exposure weakens the jacket). This diagram visually explains that RG316 reliability is “layered,” field failures usually begin in one layer and propagate, and the overlap of multiple stressors (bending, heat, vibration) accelerates degradation—interactions that are hidden by looking only at the headline temperature rating.

RG316 reliability is layered. PTFE dielectric governs impedance stability. The braided shield provides RF containment and mechanical reinforcement. The FEP sheath protects against environment and abrasion. Field failures usually begin in one layer and propagate.

Excessive bending stresses the dielectric. Vibration fatigues the braid. Chemical exposure weakens the sheath. When these stressors overlap—tight bends near heat sources combined with vibration—degradation accelerates. Looking only at the headline temperature rating hides these interactions.

Mil-spec vs commercial RG316: when the tighter spec justifies the price

Mil-spec RG316 cable assemblies typically offer tighter dimensional control, more consistent braid coverage, and more extensive screening. That consistency matters when failure is unacceptable or when assemblies are inaccessible after deployment.

In controlled commercial environments, standard industrial-grade RG316 often performs adequately. The premium for mil-spec is justified when temperature extremes, vibration, and long service life overlap. The decision is rarely about RF performance alone. It is about variability and confidence over time.

Can you mix RG316 cable with RG58 or LMR runs safely?

Keep the entire path at 50 ohms while changing cable families

Use RG316 cable only for tight internal runs and RG58/LMR for long or outdoor segments

This diagram, through side-by-side comparison or a system schematic, clearly distinguishes the roles of RG316 and LMR100 (as a representative of the RG58/LMR family). The image might visually show the RG316 Coax Cable as slender and flexible, annotated as suitable for short internal routing due to its flexibility and heat tolerance. The LMR100 Coax Cable appears relatively thicker and more robust, annotated as suitable for long or outdoor segments due to its lower loss and stronger mechanics. The diagram might also place them within a simple system block diagram, showing RG316 used for the internal jumper from PCB to bulkhead connector, and LMR100 for the longer connection from the bulkhead to the external antenna. This image aims to illustrate a common and stable design pattern: Reserve RG316 for short internal routing where flexibility and heat tolerance matter, and use RG58/LMR for longer or external segments, thereby leveraging their respective strengths and simplifying both mechanical design and field service.

Document transitions clearly so technicians don’t swap cables blindly

Turn RG316 cable reliability targets into a simple test plan

Define basic acceptance tests: continuity, insulation resistance, and VSWR at key bands

For RG316 cable, acceptance testing is usually simple. Continuity checks confirm that the center conductor and shield are intact after termination. Insulation resistance screens out damage caused during stripping or crimping. These two tests alone eliminate most early failures on short internal harnesses.

VSWR or return-loss checks should be done only at frequencies the product actually uses. Short RG316 runs can look acceptable at low frequency even when routing or termination has already compromised high-frequency behavior. Testing at an irrelevant band adds effort without adding confidence. The intent is to verify that the installed cable behaves like a short, well-controlled interconnect, not to characterize the cable itself.

For systems where link margin is tight, teams often cross-check results against expectations already established during jumper-level analysis, such as those outlined in RG316 coax cable jumpers: length and loss planning.

Add environmental tests: temperature cycling, vibration, and bend-fatigue for rg316 coax cable

Electrical tests alone do not expose most long-term rg316 coax cable issues. Temperature cycling reveals where differential expansion loads the cable or its terminations. Failures tend to appear during transitions rather than during steady soak.

Vibration testing highlights whether fixation points are placed correctly. Shield fatigue almost always initiates near connectors or clamps. If the cable survives vibration without measurable RF change, routing is usually acceptable.

Bend-fatigue testing matters only when the cable moves in service. When it does, the test must mirror the real motion. Random bending produces noise, not insight. Defined bend locations and repeatable motion expose the actual failure mode.

Decide when to require 100% testing vs audit sampling for production lots

Not all RG316 assemblies carry the same risk. Short internal jumpers that remain accessible after assembly can often be handled with audit sampling. Harnesses buried inside sealed enclosures cannot.

The decision is rarely about cost per test. It is about replacement cost and downtime. A single field return usually outweighs the cost of screening an entire lot. Treating all RG316 cables as identical risk is where most test strategies break down.

Use recent micro-coax and RG316 market behavior in design choices

Note how micro-coaxial cable assemblies are growing with 5G, IoT, and aerospace

The increased use of RG316 cable and similar micro-coax types follows enclosure pressure, not RF novelty. Radios move closer to antennas. Power density increases. Internal temperatures rise. The RF interconnect is forced into smaller volumes with less thermal margin.

Micro-coax adoption reflects that constraint. Designers accept narrower mechanical margins in exchange for routing flexibility and temperature tolerance. RG316 remains common because it occupies a workable middle ground, not because it excels in any single dimension.

Track RF coaxial cable assemblies demand in telecom, automotive, and medical systems

Telecom, automotive, and medical equipment increasingly rely on short internal RF links rather than long external feeders. These systems value predictable aging behavior over peak performance. A cable that behaves the same after years of thermal cycling is preferred to one that looks ideal during initial test.

This is one reason RG316 continues to appear alongside heavier families rather than being replaced by them outright. For broader context across cable families and application boundaries, teams often revisit the overview in the RG Cable Guide during architecture reviews.

Use RG316 cable where miniaturization and high temperature intersect

Which RG316 cable questions should be settled before release?

Summarize pre-release checklist items for internal RG316 harnesses

Before release, the following points should not be debated. Minimum bend radius must be respected in the assembled state, not just in CAD. Fixation points must limit vibration rather than lock the cable rigidly. Routing must avoid local heat sources rather than relying on average enclosure temperature. Connector transitions must be supported so the cable is not carrying unintended load.

If any of these rely on “it should be fine,” the design is not finished.

Align design, manufacturing, and field teams on when RG316 is mandatory vs optional

Most RG316-related field issues originate after handoff. Manufacturing substitutes a visually similar coax. Field service replaces a failed cable with what is available. These decisions are usually made in good faith.

Drawings and specifications need to state clearly where RG316 cable is required and where alternatives are acceptable. Ambiguity leads to silent design drift.

Lead into recurring questions raised during reviews and service

FAQ

How tight can RG316 cable be bent inside a finished enclosure?

Six times the outer diameter is commonly tolerated for static routing, but this leaves little margin. Designs exposed to vibration or temperature cycling usually require larger radii to remain stable over time.

Is RG316 cable truly suitable for continuous high-temperature operation?

Material ratings allow high temperatures, but continuous operation near the upper limit accelerates aging. Many systems keep long-term exposure well below the headline rating and rely on RG316 primarily for short, hot internal segments.

What actually causes most RG316 failures in the field?

Tight bends near connectors, vibration-induced shield fatigue, routing through localized hot zones, and mechanical load transferred into PCB pads are the most common contributors. These issues develop gradually.

When should RG316 cable be replaced in fixtures or 24/7 systems?

Replacement is usually triggered by measurable RF drift, visible jacket degradation, or changes after vibration or thermal cycling. Time alone is rarely the deciding factor.

Can RG316 be replaced with RG174 or RG178 during service?

Only after verifying temperature rating, attenuation, and mechanical behavior. These cables are not interchangeable in environments involving heat or vibration.

What information should never be missing from an RG316 internal harness drawing?

Cable type, length tolerance, minimum bend radius, connector orientation, fixation locations, expected temperature and vibration class, and acceptance tests. Missing information tends to be filled later with assumptions.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.