Reverse Polarity Protection Circuit Design Guide

Dec 26,2025

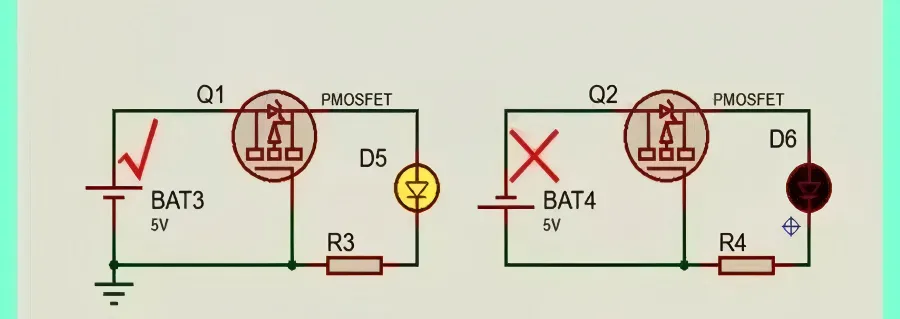

This figure serves as the introductory schematic of the document, showcasing an example of a reverse polarity protection circuit involving multiple components (e.g., Q1, Q2 P-MOSFETs, R3, R4 resistors, D5, D6 diodes, BAT3, BAT4 batteries). It is not a specific complete design but acts as a visual lead-in to the document's theme: how reverse polarity protection circuits are handled in practice. It emphasizes their importance at the intersection of power integrity, thermal limits, and long-term reliability.

Reverse polarity damage rarely makes a scene. Most of the time, nothing dramatic happens—no sparks, no smoke. A connector gets flipped, power flows the wrong way for a fraction of a second, and a board that looked perfectly healthy moments earlier is suddenly beyond repair.

That’s why a reverse polarity protection circuit shouldn’t be treated as a checkbox feature. In real products, it sits at the intersection of power integrity, thermal limits, and long-term reliability. When the design is right, it quietly does its job. When it isn’t, it becomes the kind of failure that shows up months later in the field and is nearly impossible to reproduce on demand.

This guide focuses on how reverse polarity protection is handled in practice—from early architecture decisions to design choices that survive repeated bench testing and small production runs.

How do I quickly choose between a diode, MOSFET, or ideal-diode controller?

The fastest way to lose time is to start by comparing parts. A more reliable approach is to step back and look at system context first, letting that eliminate entire classes of solutions before any datasheet ever comes into play.

Before opening a component library, I usually walk through three questions that narrow the design space quickly and predictably.

What kind of power source am I protecting?

This circuit diagram appears in the discussion section about “What kind of power source am I protecting?”. It displays a simple power input circuit fragment (e.g., 5V IN, connector, switch, diode D2, resistor R14) to help illustrate how the power supply topology (single-supply, dual-supply, battery-powered, hot-plug capable, etc.) fundamentally determines which reverse polarity protection solutions are viable or not. It visually emphasizes the importance of making decisions based on system context early in the design phase, rather than by directly comparing components.

The supply topology quietly determines what will and won’t work. In a single-supply system with fixed wiring and modest current, a diode-based reverse polarity protection circuit is often sufficient. It may not be elegant, but it is predictable and forgiving, which counts for a lot in early-stage hardware.

Dual-supply systems or designs with redundant inputs change the equation. Here, diode losses start to matter, both in terms of voltage drop and heat. MOSFET-based approaches—or eventually ideal-diode controllers—tend to scale better as current increases.

Battery-powered systems with hot-plugging are where many designs that “worked on the bench” fall apart. Intermittent contact and uncontrolled reverse current paths demand tighter control, often pushing the design toward PFET or controller-based solutions. From experience, reverse polarity events in these products are frequently caused by partial insertion rather than someone forcing a connector backward, which makes startup behavior especially critical.

Which constraint dominates: cost, efficiency, or thermal headroom?

You can usually optimize two of these. Rarely all three.

Cost-driven designs still favor diodes. They require few parts, minimal layout effort, and allow fast bring-up. Efficiency-driven designs, on the other hand, benefit far more from MOSFET-based reverse polarity protection once current rises above a few hundred milliamps. Thermally constrained designs sit somewhere in between, but even a low forward voltage diode can become problematic once current climbs past an amp and copper area is limited.

If your protection choice actively works against your primary constraint, it will almost always come back to bite you later—typically during validation rather than design review.

Three scenarios that show up again and again

Some patterns repeat across industries. Low-power sensor boards under a few hundred milliamps usually tolerate a low forward voltage diode without issue, as the voltage drop rarely threatens regulation. At the other end, 12 V industrial loads in the 1–5 A range expose the limits of diode-only solutions quickly, making MOSFET-based reverse polarity protection the practical baseline. Battery-powered equipment with user-accessible connectors often benefits from PFET high-side solutions or ideal-diode controllers to reduce reverse current and unpredictable startup behavior.

When teams try to push diode-only approaches into higher-current designs, the problems tend to surface as thermal stress and shrinking voltage margins. Those trade-offs—especially around loss and heat—are discussed in more detail in our analysis of real-world diode-based reverse polarity protection trade-offs in the Reverse Polarity Protection Diode Design Guide, which pairs well with this section when deciding how far “simple” can realistically go.

How do I set acceptable limits for Vf and RDS(on) under tight drop budgets?

Estimating diode loss without overthinking it

For diodes, the math is straightforward. The voltage drop is approximately equal to the forward voltage Vf, and power dissipation is simply Vf multiplied by load current. Where designs often go wrong is assuming datasheet values reflect real operating conditions.

Consider a common example: a diode with a forward voltage of 0.45 V carrying 2 A of current dissipates roughly 0.9 W. On a compact PCB, that single component can easily become the hottest spot on the board. Datasheet Vf is usually specified at 25 °C, but junction temperature rises quickly in small packages, and effective losses often end up higher than early calculations suggest.

MOSFET loss: smaller numbers, different pitfalls

MOSFET-based reverse polarity protection looks attractive because the apparent voltage drop is much lower. The equations are simple—voltage drop equals current times RDS(on), and power loss equals current squared times RDS(on). The challenge is temperature.

As the MOSFET heats up, RDS(on) increases. Ignoring that shift leads to optimistic results that rarely hold up on real boards. A common early-stage correction many engineers apply is to assume an effective RDS(on) about 1.3 times the 25 °C datasheet value. This factor isn’t especially conservative; it reflects what typically happens on standard FR-4 boards without aggressive thermal design.

Brown-out margins and UVLO awareness

It’s always safer to work backward from the system’s minimum operating voltage. If Vout equals Vin minus the protection drop, and that value dips below Vmin even briefly, resets and intermittent failures become likely. A surprising number of “mystery resets” traced back during validation turn out to be nothing more than underestimated voltage drop in the reverse polarity protection circuit.

One final oversight is worth calling out. Loss calculations are often done at steady-state current, but failures frequently happen at startup, when inrush or transient current briefly doubles. If your protection barely survives nominal conditions, it probably won’t survive repeated hot-plug events in the field.

What extra transients must I consider on a 12 V reverse polarity protection circuit?

Once a design moves onto a 12 V rail, reverse polarity protection stops being a purely static exercise. On paper, the voltage is still well within the comfort zone of most diodes and MOSFETs. In real hardware, though, the problems usually arrive through the wiring rather than the silicon.

Most 12 V systems are fed through cables, sometimes long ones. Those cables store energy, and they release it when current changes abruptly. A reversed connector that is quickly corrected, or a loose plug that chatters during insertion, can generate short but sharp voltage excursions. These events are easy to miss during bench testing because they don’t look dramatic, yet they are exactly what slowly degrade protection components.

This is why a 12v reverse polarity protection circuit that looks fine under steady-state conditions can still fail after weeks of normal use.

Cable inductance and why it matters during reverse events

Cable inductance becomes visible only when current is forced to change quickly. During a reverse connection or a sudden unplug, the energy stored in the cable has to discharge somewhere. If the reverse polarity protection stage is the first solid junction it encounters, that stage absorbs the stress.

Over time, repetitive stress shows up as leakage increase, threshold drift, or outright breakdown. The schematic never changes, but the margin quietly disappears. This is one of the reasons reverse polarity protection in 12 V systems must be evaluated during connect and disconnect events, not just with a static reverse voltage applied.

TVS coordination is about order, not just presence

Adding a TVS diode is often treated as a checkbox item. What matters more than its presence is where it sits in the current path. If the TVS is placed electrically behind the reverse polarity protection device, fast transients may never reach it in time.

In practice, a more robust ordering is to place the TVS immediately after the connector and ahead of the reverse polarity element. That way, high-frequency spikes are clamped before they can propagate through a MOSFET body diode or a diode junction that was never intended to handle surge energy.

The clamping voltage also has to be coordinated with the voltage ratings of the downstream device. Poor coordination can lead to both devices conducting simultaneously under stress, concentrating energy instead of dissipating it. This interaction is often overlooked when reverse polarity protection is designed in isolation.

Inductive loads add a return-path problem

Relays, solenoids, and motors complicate reverse polarity protection because they store energy magnetically. When power is removed—especially during a fault or reverse event—that energy looks for a path back to the source.

If the reverse polarity protection circuit does not provide a controlled return path, the current may flow through unintended structures, including MOSFET body diodes or parasitic paths inside the PCB. These currents are rarely catastrophic in a single event, but they shorten component life.

This is why in many industrial designs, reverse polarity protection is considered together with flyback diodes and transient suppression rather than as a standalone block.

How do I drive the gate and avoid body-diode pitfalls in PFET reverse polarity protection?

PFET-based reverse polarity protection remains popular because it provides high-side protection while keeping the system ground stable. For communication-heavy or mixed-signal designs, that advantage is hard to ignore. Most failures, however, come from gate-drive mistakes rather than from MOSFET selection.

Early prototypes often appear to work because they have not yet encountered stressful conditions such as slow input ramps or repeated hot-plugging.

Gate reference mistakes don’t fail loudly

In a high-side PFET configuration, the source follows the input voltage. The gate must be referenced to that moving node, not to ground. When the gate is inadvertently tied—directly or indirectly—to ground, the PFET can partially turn on under reverse or slow-ramp conditions.

The result is intermittent conduction that depends on timing, temperature, and ramp rate. These failures are notoriously difficult to reproduce on demand, which is why they often escape early validation.

A well-defined gate bias, with clear pull-up or pull-down paths and controlled discharge behavior, is essential for predictable PFET reverse polarity protection.

Body diode conduction during startup is easy to underestimate

Every MOSFET includes a body diode, and in reverse polarity protection circuits, that diode may conduct before the gate reaches its intended bias. This typically happens during hot-plug events or slow-rising input voltages.

Even brief body-diode conduction can partially charge downstream bulk capacitors. When the PFET finally turns on, the system experiences an unexpected inrush profile. Brown-out detectors and UVLO circuits may react poorly, creating resets that look unrelated to the protection circuit at first glance.

Designers sometimes address this with RC networks on the gate. Others decide that once these edge cases matter, discrete PFET solutions are approaching their limits.

High-side versus low-side: the ground reference trade-off

Low-side MOSFET protection simplifies gate drive, but it shifts the system ground during faults. In digital-only systems, that may be tolerable. In mixed-signal, RF, or communication systems, ground movement often causes more problems than it solves.

High-side PFET reverse polarity protection avoids ground disturbance, but it makes voltage headroom more precious. Once protection losses start consuming available margin, downstream regulation stages feel the impact immediately. This interaction becomes especially visible in designs where reverse polarity protection sits ahead of a boost stage, such as those discussed in 5V to 12V Boost Converter Design in Practice, where even small input losses translate directly into thermal and efficiency penalties.

Failure cases worth planning for

Two scenarios deserve explicit consideration. The first is a downstream short circuit, where the PFET must survive long enough for upstream protection to act or fail safely. The second is reverse current injection from another supply rail, which can be just as destructive as an external reverse connection.

These are often the points where PFET-based designs stop scaling gracefully and where ideal diode controllers start to look like a controlled, rather than excessive, upgrade.

When does an ideal diode controller make more sense?

Ideal diode controllers tend to enter the conversation later than they should. Many teams view them as an expensive refinement rather than a structural change in how reverse current is controlled. In practice, the moment a design crosses certain thresholds, discrete solutions stop scaling gracefully.

One clear signal is current. Once sustained load current reaches a few amps, the combined losses of a diode—or even a well-chosen MOSFET—begin to dominate thermal behavior. At that point, the protection circuit is no longer a passive safeguard; it becomes one of the primary heat sources on the board.

Another signal is system topology. Redundant supplies, OR-ing paths, and long cable runs all increase the likelihood of reverse current events that are not strictly polarity-related. Ideal diode controllers handle these conditions explicitly, rather than relying on body diodes and timing assumptions.

In systems where uptime matters, this predictability often outweighs the added BOM cost.

Efficiency, control, and what you actually gain

An ideal diode controller does more than reduce voltage drop. It actively monitors forward and reverse current and drives the MOSFET accordingly. That means reverse conduction is blocked even when downstream rails remain energized, something discrete PFET solutions can struggle with under certain conditions.

Thermally, the benefits compound. Lower voltage drop reduces steady-state dissipation, which lowers junction temperature, which in turn stabilizes electrical parameters. Over time, that stability shows up as fewer marginal failures and less performance drift.

There is also an EMI angle that doesn’t get discussed enough. Controlled turn-on and turn-off behavior reduces the abrupt current transitions that excite cable inductance and parasitic loops. In noisy industrial environments, that alone can justify the controller.

How should I lay out copper and return paths for SOD-323F and QFN parts together?

This figure appears on Page 10 in the chapter dedicated to layout discussion. It likely takes the form of a top-down or cross-sectional view, specifically showing how to lay out small SOD-323F diodes and QFN-packaged MOSFETs or controllers on the same PCB. Its core focus is to explain current return paths, copper area (as the primary thermal path), the use of thermal vias, and ensuring proper connection of QFN exposed pads to low-impedance planes. It aims to address the common issue where boards still run hotter than expected or show inconsistent behavior despite having a correct schematic and appropriately rated components.

Layout is where many reverse polarity protection designs quietly fail. The schematic is correct, the parts are rated appropriately, yet the board still runs hotter than expected or shows inconsistent behavior between builds.

The reason is usually current return paths.

Reverse polarity protection sits at the power entry point, which means it handles large currents and fast transients. The copper around it must be treated as part of the circuit, not just mechanical support.

Copper area, not just trace width

For small packages like SOD-323F diodes, copper area is often the only meaningful thermal path. Simply meeting minimum trace width requirements is rarely sufficient. Extending copper pours on both sides of the board, stitching them with vias, and keeping the loop area compact all contribute more to temperature reduction than swapping to a slightly lower-Vf part.

QFN-packaged MOSFETs and controllers introduce a different constraint. Their exposed pads are excellent thermal conduits, but only if they are properly tied into a low-impedance plane. A floating thermal pad is worse than no pad at all.

Manufacturability still matters

Clear polarity marking, unambiguous silkscreen orientation, and sensible solder mask openings reduce assembly errors. In production, many reverse polarity failures are not electrical at all—they are caused by rotated diodes or marginal solder joints that only fail under heat.

Designing for AOI and reflow repeatability is part of protection design, even if it doesn’t show up in simulations.

How do I validate from bench to small-batch production?

Validation is where reverse polarity protection earns its keep. A circuit that survives one reversed connection on the bench has not been validated. It has merely been lucky.

Effective validation starts by assuming that the protection will be stressed repeatedly and unpredictably.

Bench testing without collateral damage

A current-limited bench supply is essential. Reverse polarity should be applied deliberately and repeatedly while monitoring input current, voltage drop, and component temperature. Incremental increases in current reveal thermal behavior long before catastrophic failure.

Series protection—such as temporary resistors or electronic loads—can help prevent damage during early testing without masking real failure modes.

Thermal observation and event logging

Thermal imaging is invaluable, even if used informally. Identifying hot spots during reverse events often reveals current paths that were not obvious from the layout.

Repeated plug–unplug cycles should be logged, especially in 12 V systems. Many failures are cumulative rather than instantaneous.

Reverse-Polarity Drop & Loss Quick Estimator

This quick estimator is intended for early-stage decisions, not final sign-off.

Inputs

- Load current I (A)

- Diode forward voltage Vf (V)

- MOSFET RDS(on) (Ω), multiplied by 1.3 for temperature

- Operating time t (h)

- Minimum system voltage Vmin (V)

Formulas

- Diode:

- ΔV = Vf

- P = Vf × I

- E = P × t

- MOSFET:

- ΔV = I × RDS(on)

- P = I² × RDS(on)

- E = P × t

Decision checks

- If Vin − ΔV < Vmin, the protection scheme is not viable as-is

- If P > 5% of load power, thermal mitigation or an upgraded topology should be considered

Outputs

- Recommended approach (diode, MOSFET, or controller)

- Copper and thermal guidance

- Validation checklist (thermal imaging, hot-plug cycles, transient observation)

FAQ

How do I size reverse polarity protection for cold-start brown-out margins?

Work backward from Vmin and assume worst-case drop during inrush, not nominal load.

What gate-drive mistakes cause PFET reverse polarity circuits to fail intermittently?

Referencing the gate to ground instead of the source and ignoring slow-ramp conditions.

When does an ideal diode controller outperform a low-Vf Schottky on 12 V rails?

When current, thermal stress, or reverse current scenarios become recurring rather than exceptional.

How can I test reverse tolerance without risking my bench supply or DUT?

Use a current-limited supply and staged reverse events, increasing stress gradually.

What PCB cues prevent SOD-323F parts from overheating?

Generous copper area, short loops, and thermal vias matter more than part swaps.

How do I combine a TVS clamp with reverse protection correctly?

Clamp first, isolate second, and coordinate voltage ratings carefully.

What is a practical upgrade path as current grows?

Diode to MOSFET, MOSFET to controller—when losses and unpredictability become unacceptable.

Closing Remarks

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.