Outdoor Omni Antenna: Selection, IP67 & Mounting Guide

Dec 17,2025

Serving as the article's opening cover image, this picture visually presents the diverse applications of outdoor omnidirectional antennas. It emphasizes that selecting the right antenna is less about chasing the highest gain and more about understanding your site’s geometry, signal paths, and environmental exposure. By depicting antenna deployments in various complex environments (e.g., warehouses, poles, rooftops), this image sets the visual foundation for the subsequent in-depth discussion on core topics like gain selection, connectors, sealing ratings, and installation details.

Which outdoor omni antenna class fits your site and spectrum?

This image provides a concrete response to the opening question: “Which outdoor omni antenna class fits your site and spectrum?”. It transforms abstract selection principles into a clear, actionable decision matrix. Engineers can quickly look up the corresponding typical gain, antenna form, connector (e.g., N-type, SMA), and mounting method (e.g., wall mount, mast mount, magnetic base) based on their application frequency (e.g., 2.4 GHz, 5/6 GHz, LTE/5G) and scenario (e.g., gateway, rooftop AP, backhaul). This chart is a core tool for preliminary technical selection.

Selecting the right outdoor omni antenna is less about chasing the highest gain and more about understanding your site’s geometry, signal paths, and environmental exposure. Whether you’re building a Wi-Fi mesh for a warehouse, an IoT gateway on a pole, or a small rooftop access point, the right antenna class defines long-term stability and link reliability.

In typical deployments, low-gain 3 dBi antennas serve compact gateways or sub-GHz IoT nodes, where wide vertical coverage matters more than distance. Mid-gain 5–6 dBi models dominate for outdoor Wi-Fi and 2.4 GHz networks, balancing range and consistency. Anything beyond 8 dBi shifts into “corridor coverage” or high-gain omni antenna territory—excellent for straight paths but risky for multi-level or urban cluttered areas.

| Application Scenario | Frequency Bands | Typical Gain (dBi) | Antenna Type | Connector Base | Mounting Style |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IoT gateway | 2.4 GHz / Sub-GHz | 2 – 3 | Short whip / dome | SMA / RP-SMA | Wall or bracket |

| Rooftop AP | 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz | 5 – 6 | Fiberglass omni | N-female | Mast mount |

| Campus or backhaul | 5 / 6 GHz | 8 – 12 | High-gain omni | N-female | Pole clamp |

| Vehicle / mobile | LTE / 5G | 3 – 6 | Magnetic mount | SMA | Magnetic base |

Connector choice makes or breaks outdoor performance. N-female bases provide robust mechanical sealing and low RF loss—standard in most rooftop or mast installations. SMA or RP-SMA connectors, found on compact enclosures or weatherproof boxes, save space but must be sealed with self-amalgamating tape or cold-shrink sleeves. For better mechanical consistency, standardized mast clamp kits (like those on TEJTE’s mast mount antenna series) prevent rotation and ensure steady torque under wind load.

While rubber duck antennas or FPC antennas might serve indoor IoT devices, they fail outdoors due to detuning from enclosure metal or humidity drift. For genuine outdoor reliability, fiberglass-shelled omni antennas with IP67 seals and UV-resistant radomes stay stable across years of temperature cycles.

How do you verify IP67 sealing and UV stability for multi-year exposure?

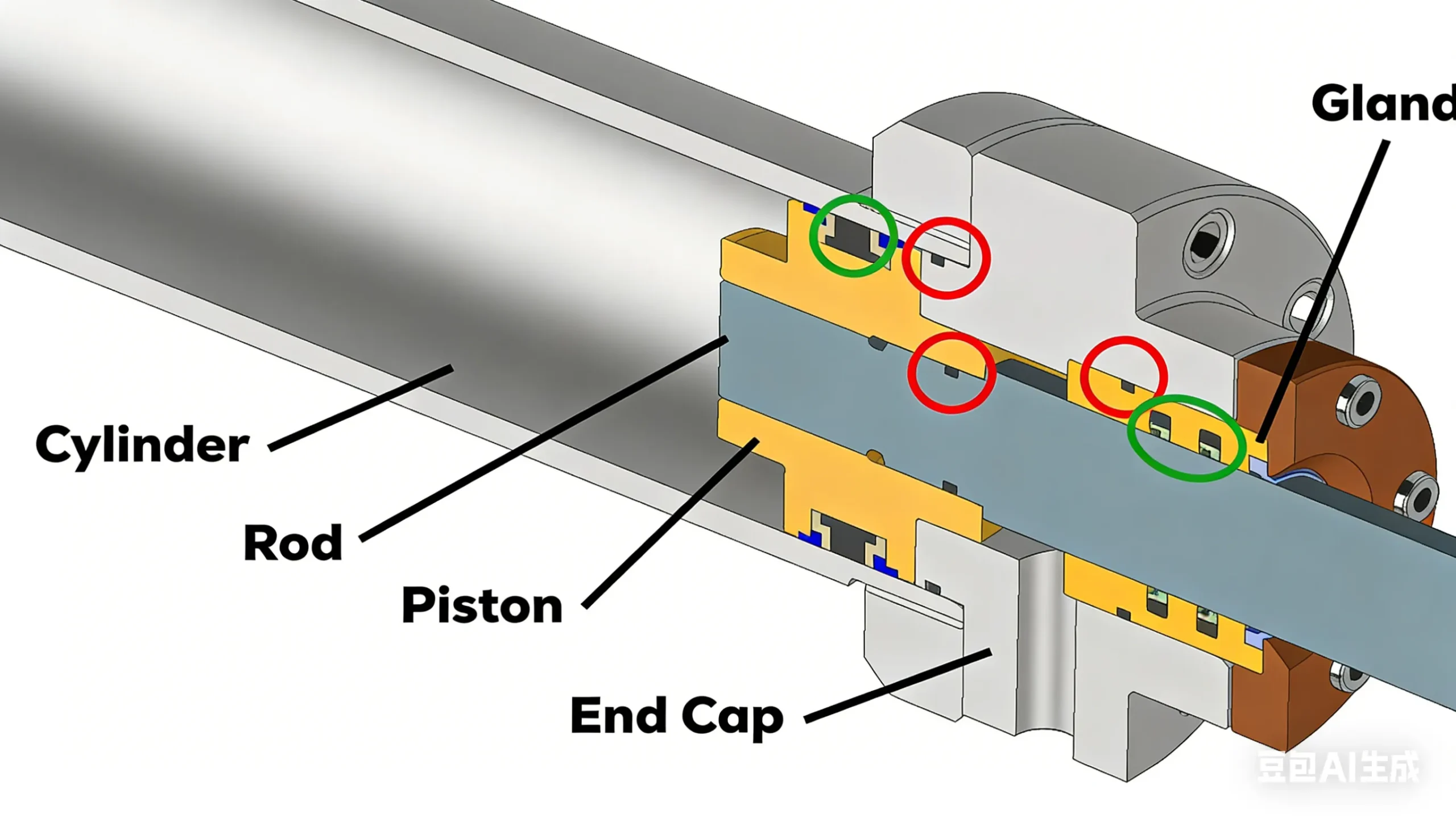

Where leaks actually happen

The usual suspects are O-rings around connector bases, cable glands, and vent plugs meant for pressure equalization. A properly compressed O-ring should deform slightly without extrusion. Glands must grip the cable evenly without cutting into the jacket. Vent plugs should breathe but not leak, a detail many low-cost imports ignore.

Before installation, engineers often run a field water test—either brief submersion or a 10-minute pressure spray. If condensation forms inside the radome, it’s a sign of poor sealing. For contract builds, insist on IP67 certification with lab documentation; it’s the only way to ensure every batch meets spec.

Radome and environmental durability

Located in the crucial chapter “How do you verify IP67 sealing and UV stability for multi-year exposure?”, this image concretizes “where leaks actually happen” through an exploded schematic. It clearly shows the structure and working principle of key sealing components such as O-rings, cable glands, and vent plugs. The image emphasizes the paramount importance of these mechanical details in preventing slow moisture ingress and ensuring antenna performance stability over many years in harsh outdoor environments. It serves as a visual basis for engineers conducting incoming inspection and on-site installation checks.

Long-term exposure tests are just as vital. Choose UV-stable fiberglass or ASA plastics with at least 1000 hours of ASTM G154 UV resistance. Coastal or marine sites demand salt-fog resistance ≥480 h (ASTM B117) and corrosion-proof N-female connectors with nickel-plated or stainless housings.

A good weatherproof antenna also lists an operating range of –40 °C to +85 °C or better; for desert rooftops, even +100 °C isn’t excessive. Many engineers overlook thermal expansion until they find cracked radomes after one summer season.

In TEJTE’s IP-rated outdoor line, dual O-rings and anodized clamps maintain sealing torque for years. The mounting hardware follows the same mast torque standards used in industrial telemetry networks, ensuring both electrical and mechanical reliability without needing constant re-tightening.

What gain should you pick — 3 dBi, 6 dBi, or high-gain for corridors?

Elevation nulls and pattern trade-offs

At 3 dBi, coverage extends up and down, ideal for users on multiple floors or devices located under the antenna. Moving to 6 dBi flattens the pattern; signal travels farther but loses strength directly beneath. Beyond 9 dBi, elevation nulls appear—dead spots caused by overly narrow vertical lobes.

For multi-story or dense installations, 6 dBi is a safe ceiling. In long corridors, tunnels, or open fields, higher-gain fiberglass omnis perform beautifully—but only if the tilt angle compensates for those nulls. A small downward tilt (5–10°) often restores uniform ground coverage.

2.4 GHz / 5 GHz / 6 GHz coexistence

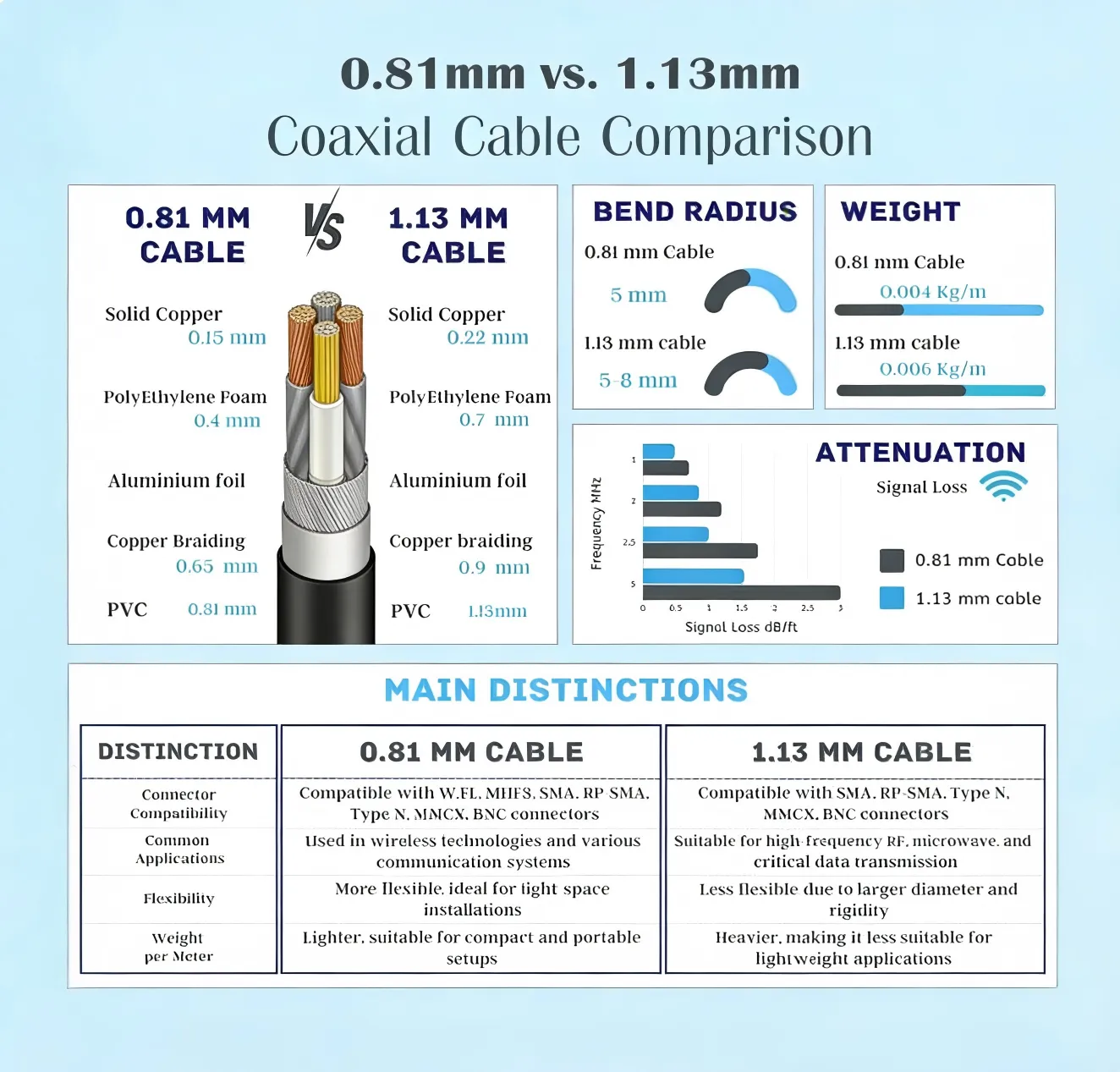

This image is part of the section discussing “Will feeder type and length silently erase your EIRP?”. It goes beyond simple loss figures to provide an extremely detailed engineering comparison. The chart not only visually displays the physical construction differences between the two commonly used micro-coax cables (e.g., conductor diameter, shielding thickness) but also systematically compares key parameters affecting actual installation and performance. This image provides comprehensive decision-making basis for engineers selecting feeder lines inside compact devices, especially when balancing flexibility, weight, connector compatibility against attenuation performance.

Tri-band access points use all three bands simultaneously. At 2.4 GHz, waves bend around walls and trees; at 6 GHz, signals are crisp but fragile. A well-tuned 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi antenna should maintain similar gain slopes across 5 GHz and 6 GHz for consistent behavior. The key metric is VSWR ≤ 1.8:1 across the range—lower is better.

When multiple outdoor units share a mast, spacing is crucial. Keep ≥ 1 m vertical or ≥ 3 m horizontal separation to minimize coupling. Even a metal railing can detune the lower antenna, shifting its resonant point. If you’re unsure, check TEJTE’s guidelines on ground clearance and antenna detuning inside their RF layout resources at tejte.com.

Will feeder type and length silently erase your EIRP?

Cable loss — the quiet thief of signal strength

| Feeder Type | Typical Loss @ 2.4 GHz | Where It's Used | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| LMR-400 | ≈ 0.14 dB/m | Rooftop & tower runs | Low loss, heavier cable |

| LMR-240 | ≈ 0.26 dB/m | Medium lengths | Easier to route |

| 1.13 mm coax | ≈ 0.60 dB/m | IoT modules | Use < 0.5 m |

| 0.81 mm coax | ≈ 0.80 dB/m | Compact boards | Keep very short |

Connectors steal energy too. Each pair costs about 0.15 dB, sometimes more when threads corrode. After months outdoors, one loose fitting can turn a solid link into a constant timeout. For rooftop jobs, most installers now choose N-type connectors for the main feed and limit SMA use to short internal pigtails. The difference in sealing is huge; an N-female base with proper torque will stay dry for years, while an SMA joint may fail after a single winter.

On commercial systems like TEJTE’s mast mount antenna kits, all outdoor connectors ship pre-greased and sealed to prevent that slow moisture creep most people discover too late.

Where should you place the omni to avoid detuning and shadows?

Stay clear of metal and obstructions

Keep at least one full wavelength—roughly 12 cm at 2.4 GHz—between the antenna and any large metallic surface. HVAC pipes and parapets reflect energy and carve notches into coverage zones. A small mast extension or offset bracket often fixes what hours of tuning can’t. In practice, you want the lowest part of the antenna to clear the top edge of any nearby wall.

On narrow rooftops, installers sometimes skip modeling and simply walk the site with a 2.4 GHz Wi-Fi analyzer, marking dead spots before drilling holes. It’s crude but effective. The signal map you draw on paper often saves one costly reinstall.

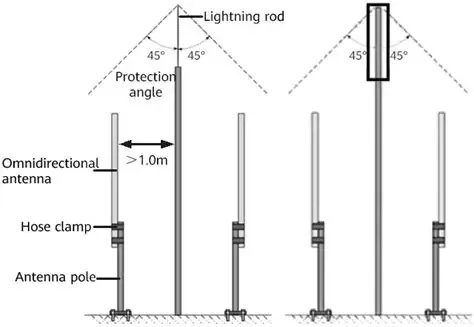

Mind your neighbors — antenna spacing

Corresponding to the subsection “Mind your neighbors — antenna spacing”, this image is a key visual guide for solving interference issues in multi-antenna systems. It intuitively demonstrates the spacing rules that must be followed when installing multiple omni antennas on the same pole (vertical separation often matters more than gain). The diagram likely annotates the minimum recommended distances between antennas of different or same bands, emphasizing that even nearby objects like metal railings can cause antenna detuning. This image is the direct basis for translating theoretical isolation requirements (e.g., 25 dB) into practical installation layouts.

When several omnis share a single pole, vertical separation matters more than gain. A good rule is one meter apart for same-band units, and at least 1.5 m when frequencies overlap. Cross-polarized pairs can sit closer, but measure isolation before going live; 25 dB or more keeps self-interference in check.

During test deployments documented by TEJTE, even tiny hardware choices—such as screw length or bracket thickness—shifted resonance noticeably. Those findings now inform their ground-clearance design rules published in their antenna layout resources at tejte.com. Small, almost invisible tweaks there often mean the difference between theory and reliable coverage.

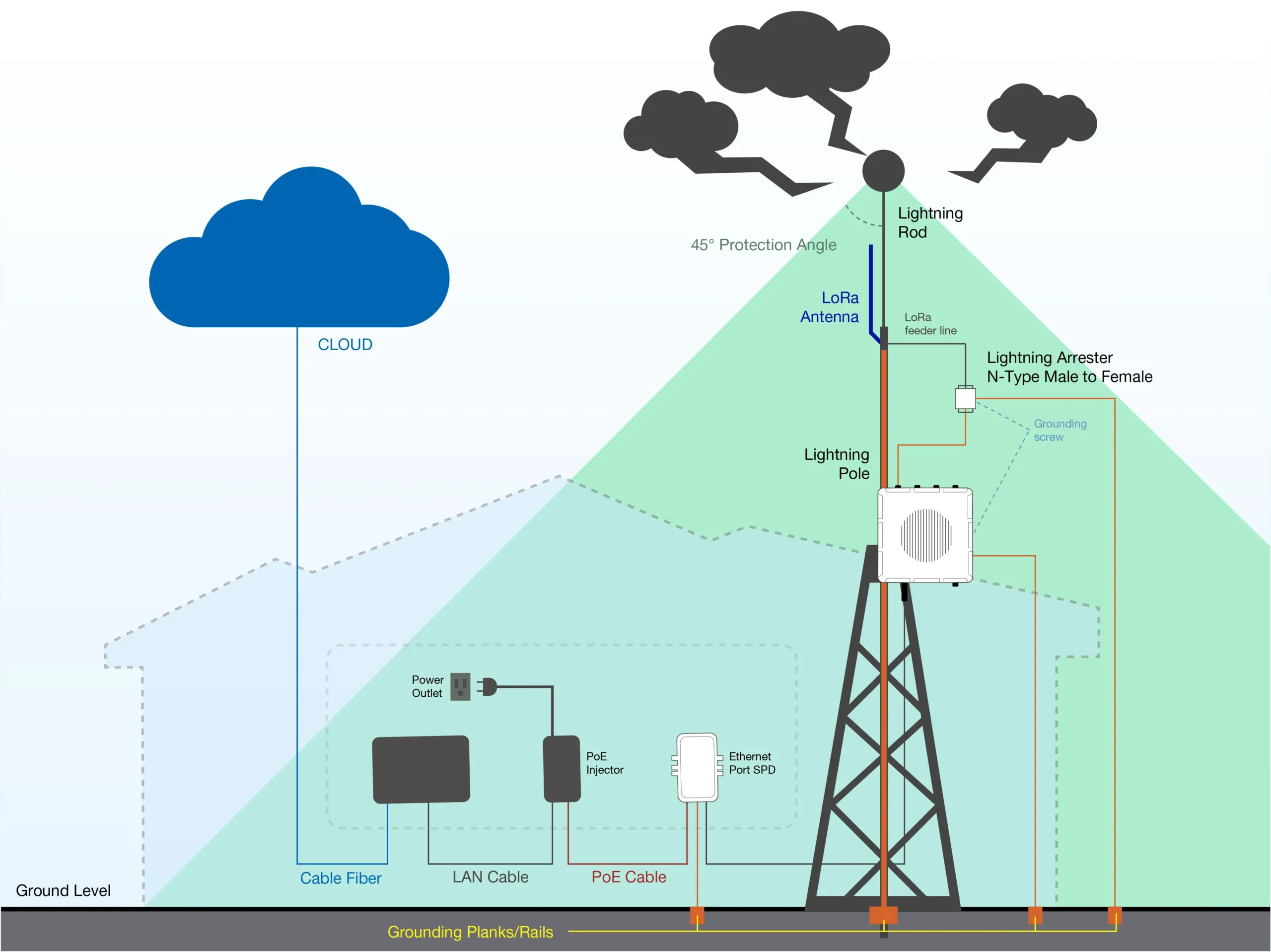

Do you need surge protection and mast bonding?

Arrestors and bonding — where to put them

The lightning arrestor should sit close to the building entry, bonded to the same ground system as the rest of your equipment. Keep the ground strap short and wide; flat braid beats round wire because it lowers inductance. Paint on mast sections blocks continuity, so scrape or use serrated washers to guarantee metal-to-metal contact.

If your system includes stacked antennas, bond each section of mast individually. Field crews sometimes assume the clamps make contact, only to find floating voltages during a storm. TEJTE’s outdoor kits simplify this with pre-drilled bonding lugs and optional gas-tube arrestors tuned for 50 Ω lines—meeting IEC 61000-4-5 surge standards without adding measurable loss.

Mechanical weatherproofing still matters

Located in the safety-critical chapter “Do you need surge protection and mast bonding?”, this image clearly depicts the standard engineering practice for lightning protection: the correct placement of the arrestor (near building entry), low-inductance grounding connection (using flat braid), and equipotential bonding to ensure electrical continuity across all metal mast sections. The image integrates detailed suggestions from the text, such as “scrape paint” and “use serrated washers,” into a complete system diagram. It is the core installation reference for preventing equipment damage from direct lightning strikes or induced surges.

Good grounding won’t save you if rain runs straight into a connector. Always loop the cable downward before it enters an enclosure; that drip loop forces water to fall off naturally. Use UV-rated ties or Velcro straps that can flex under temperature swings, and never stretch them tight—plastic shrinks in cold weather.

A service loop of half a meter gives future technicians room to work. Without it, every replacement becomes a cable-cutting job. The loop should rest below the entry point, never above; capillary action can pull water uphill through the braid.

In practice, a well-installed weatherproof antenna looks boring: clean bends, gentle loops, all metal parts bonded. The ones that fail quickly are easy to spot—they have kinks, bright tape patches, and cables tied drum-tight. Field data from TEJTE’s deployments showed that when installers followed the bonding and loop standards, failure rates over two years dropped by more than a third.

Can you validate the installation before sign-off?

Quick alignment checks

After mounting the outdoor omni antenna, walk a 20-meter circle and log RSSI values. A balanced setup gives a clean donut pattern—within a few dB around the ring. If you see sharp dips at one azimuth, something nearby is blocking or reflecting. Adjust tilt slightly and recheck; five degrees of movement can recover several decibels. For long corridors, a mild downward tilt helps fill in elevation nulls.

For bigger sites, simple drive-tests or Wi-Fi heatmaps tell you more than hours of theoretical modeling. Modern apps like Ekahau or NetSpot make it quick enough to run during final inspection.

Finding faults without guesswork

When a system underperforms, start from the simplest component: the cable. Substitute a short known-good jumper between the radio and antenna. If the signal jumps back, you’ve confirmed feedline loss or a bad connector. Work backward step by step—cable, connectors, antenna—to isolate the issue.

Many technicians record torque and serial numbers right after installation. It feels like overkill until a failure pops up months later. With that data, you can prove whether a connector loosened or a feedline aged prematurely. These habits separate professional installs from improvisations—and they make sure your carefully chosen omni antenna performs exactly as specified.

How should you order so the PO is buildable and weather-safe?

Details that belong in every order

Located in the practical section toward the end of the article, this image serves as concrete technical visualization of “how to ensure installation quality.” It moves beyond theoretical specifications and checklists to directly show the key hands-on details involved in a professional, reliable outdoor antenna installation. The image likely highlights three points: 1) Mechanical Fixation: Showing the correct assembly sequence of U-bolts, washers, and nuts, and the torque application points, emphasizing even force distribution to prevent slippage; 2) Environmental Sealing: Demonstrating the technique of multi-layer wrapping with waterproof tape or using pre-made sealing sleeves at connectors or cable entry points, which is the crucial on-site operation for achieving long-term IP protection; 3) Electrical Bonding: Showing how the ground wire is reliably connected to a paint-free mast surface or a dedicated grounding terminal, forming a vital part of the lightning discharge path. This image aims to provide a visual example of a standardized, followable installation process for field engineers or installers.

| Item | Example | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Gain | 6 dBi ± 0.5 dB | Controls coverage height and range |

| Band set | 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz | Must match the radio ports |

| Connector | N-female | Fits outdoor feedline, seals better than SMA |

| Mounting | Dual U-clamp (35-60 mm pole) | Stops rotation under wind |

| Seal rating | IP67 / dual O-ring | Determines weather endurance |

| Feeder | LMR-240 × 10 m | Drives total link loss |

| Surge kit | Gas-tube arrestor | Saves the radio on storm nights |

| Housing | Fiberglass + UV ASA | Keeps color and shape for years |

| Compliance | RoHS / REACH / UL 94 V-0 | Needed for global shipments |

Leaving any of these out costs more time than filling them in.

On TEJTE’s spec sheets the same list appears by default, so purchasing, QA, and installers describe the antenna the same way instead of trading emails later.

Link-Budget & Feeder-Loss Mini Calculator

| Parameter | Example | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| TX Power (dBm) | 20 | Radio output |

| Antenna Gain (dBi) | 6 | 3 / 6 / 9 classes |

| Feeder Type | LMR-240 | See loss chart |

| Feeder Length (m) | 10 | Physical distance |

| Connector Pairs | 2 | ≈ 0.15 dB each |

| Frequency (GHz) | 2.4 | Operating band |

| RX Sensitivity (dBm) | -85 | Device spec |

| Path Loss (dB) | 92 | Measured or FSPL |

Feeder Loss = loss_per_m × length

Conn Loss = 0.15 × connector_pairs

EIRP = TX Power – Feeder Loss – Conn Loss + Antenna Gain

Link Margin = EIRP – Path Loss – RX Sensitivity

| Cable | Loss (dB/m) | Typical use |

|---|---|---|

| LMR-400 | 0.14 | Long rooftops |

| LMR-240 | 0.26 | Medium runs |

| 1.13 mm coax | 0.60 | Short pigtails |

| 0.81 mm coax | 0.80 | PCB links |

If your margin ends up under 6 dB, shorten the feed or upgrade the cable.

Most crews check this through TEJTE’s internal calculator before buying reels.

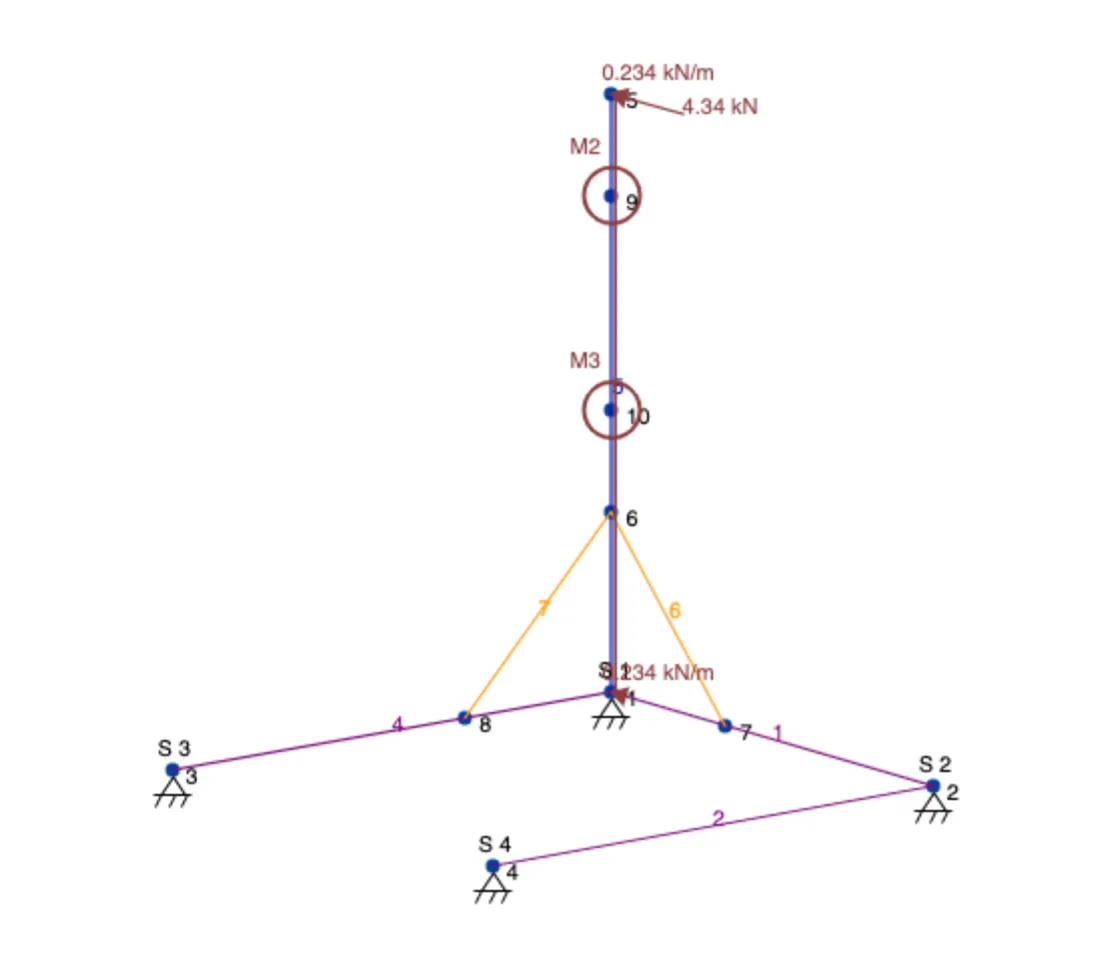

Wind-Load & Clamp-Torque Estimator

| Variable | Symbol (Unit) | Example | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wind speed | V (m/s) | 40 | Design gust |

| Area | A (m²) | 0.02 | Projected surface |

| Drag factor | Cd | 1.3 | Shape coefficient |

| Lever arm | L (m) | 0.25 | CG to clamp |

| Friction coef. | μ | 0.25 | Clamp liner |

| Mast diam. | D (mm) | 50 | Pipe size |

| Clamp count | n | 2 | Per antenna |

q = 0.613 × V² (N/m²)

F = q × A × Cd

M = F × L

Σ(T_clamp × μ / r_mast) ≥ M

On a 50 mm mast, two clamps at 8 N·m each survive ~120 km/h winds.

If the math says otherwise, add another clamp or use a textured liner.

TEJTE’s double-U hardware is already tested to these loads so installers don’t need to guess torque on rooftops.

IP67 Acceptance Checklist

As a visual representation of the “IP67 Acceptance Checklist,” this image is the final operational guide to ensure installation quality and prevent future leakage failures. It transforms the checklist table from the text into a more intuitive worksheet that on-site technicians can tick off item by item and sign. The image includes key checkpoints such as “O-ring seated, no cracks” and “Drip loop formed,” emphasizing that completing these seemingly trivial but crucial verifications before leaving the site is the last line of defense for long-term reliability.

Use this quick list before leaving the site.

Mark each line ✅ once verified.

| Check Item | Status | Field Note |

|---|---|---|

| O-ring seated, no cracks | ☐ | Slight compression visible |

| Cable gland tight | ☐ | ¼ turn past hand-tight |

| Vent plug breathable | ☐ | Membrane clean |

| Connector sealed (tape / cold-shrink) | ☐ | No air gaps |

| Drip loop formed | ☐ | Loop below entry point |

| Salt-fog test ≥ 480 h | ☐ | ASTM B117 verified |

| UV-resistant housing | ☐ | ASA / fiberglass marked |

| Labels legible after spray test | ☐ | Torque tag still readable |

| Leak test (1 m / 30 min) passed | ☐ | No moisture inside |

What’s new in 2024 – 2025 for outdoor omni setups

Tri-band APs have become the default, merging 2.4 GHz reach with 6 GHz speed.

That shift forced tighter connector tolerances—6 GHz reflections reveal every poor crimp.

The latest mast mount kits now lock azimuth mechanically, cutting installer error almost to zero.

Material science caught up too. UV-enhanced fiberglass keeps color for a decade, and new O-ring compounds stay flexible below –40 °C. TEJTE’s current weatherproof antenna family uses those upgrades along with anodized hardware so the seal survives vibration without glue.

Private-network and Wi-Fi 7 pilots also raised the bar: clients now ask for wind-load data and torque specs in every datasheet, not in fine print.

FAQ — Outdoor Omni Antenna

How much gain before nearby coverage disappears?

Around 6 dBi is the sweet spot. Above 9 dBi you’ll want a slight downward tilt.

Which sealing method actually lasts outside?

Replaceable O-rings under compression caps. Adhesive seals dry and crack by year two.

How long can the feeder be?

Keep total loss < 3 dB. For instance, 10 m of LMR-240 plus two connectors already eats ~3 dB.

Where does the surge arrestor go?

At the building entry, bonded by a short flat copper strap to the main ground bar.

How far apart should multiple omnis sit?

Give them ≥ 1 m vertically or 3 m side-to-side. More if metal handrails are nearby.

Final Thought

As a practical engineering tool at the end of the article, this image elevates “wind-load and clamp-torque” from guesswork to quantifiable calculation. It guides engineers to systematically consider variables such as wind speed, antenna area, and lever arm length, and derives through formulas the specific torque value required to prevent antenna displacement during storms. Not only does the chart provide the calculation method, but its output logic (e.g., if torque is insufficient, add clamps or shorten the overhang) also directly offers engineering improvement directions, serving as a summary of the key steps for reliable mechanical design.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.