Omnidirectional Antenna Selection & Ordering Guide

Dec 06,2025

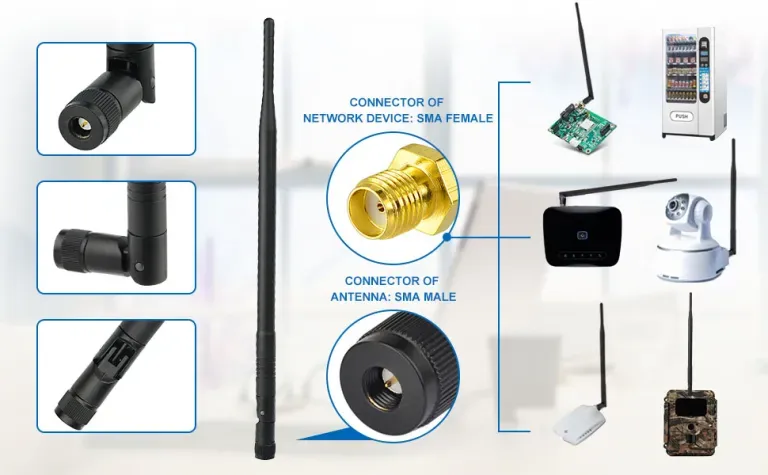

This diagram is used to emphasize the importance of physical interface matching during the initial selection of omnidirectional antennas, preventing signal loss or compatibility issues due to connector mismatches.

In every Wi-Fi or IoT deployment, the humble omnidirectional antenna quietly defines whether your signal holds steady or drops off after a few meters. It’s what allows your 2.4 GHz nodes to talk seamlessly across walls, plastic housings, or rooftops. But selecting one isn’t about choosing “2 dBi or 5 dBi.” It’s a series of small but critical engineering calls — antenna form, connector, gain, cable type, and how all these fit your housing and PCB.

When done right, your prototype performs as simulated. When wrong, you burn days debugging what turns out to be a reversed connector or 1 dB too much cable loss.

Which omnidirectional antenna form fits your device?

Compare rubber-duck (external) vs internal options (FPC/PCB/ceramic)

This chart assists engineers in selecting the most suitable antenna form based on enclosure material, space constraints, and application scenarios.

External “rubber-duck” antennas deliver solid 360° azimuth coverage and are easy to replace or reposition. At 2.4 GHz, a 2–3 dBi ducky performs almost ideally in open air. Internal antennas like FPC or ceramic save space but depend heavily on enclosure clearance and material.

In our lab builds, once metal frames or coated plastics are involved, the external version usually wins for consistency. (You’ll find similar reasoning in the 2.4 GHz antenna selection guide that deals with confined IoT nodes.)

| Form Type | Typical Gain | Mounting | Ideal Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber-duck (external) | 2–6 dBi | SMA / RP-SMA port | Routers, outdoor CPE |

| FPC adhesive (internal) | 1–3 dBi | Inside plastic case | IoT sensors |

| PCB trace | 0–2 dBi | On main board | Compact modules |

| Ceramic chip | 0–1.5 dBi | Solder-mounted | Wearables |

Map enclosure materials (ABS/PC/metal) to omni choices

This diagram explains how enclosure materials affect antenna performance, aiding designers in considering RF material properties during antenna placement.

Material transparency to RF changes everything.

- ABS / PC plastics: almost invisible to 2.4 GHz waves — great for internal omnis.

- Metal shells: act like a cage; use a bulkhead SMA to exit the housing instead.

- Carbon-filled or painted plastics: often detune FPCs; spacing and adhesive backing help.

When working with metal boxes, the best compromise is a rubber-duck omni mounted through a bulkhead SMA port. It keeps shielding intact but lets RF radiate freely.

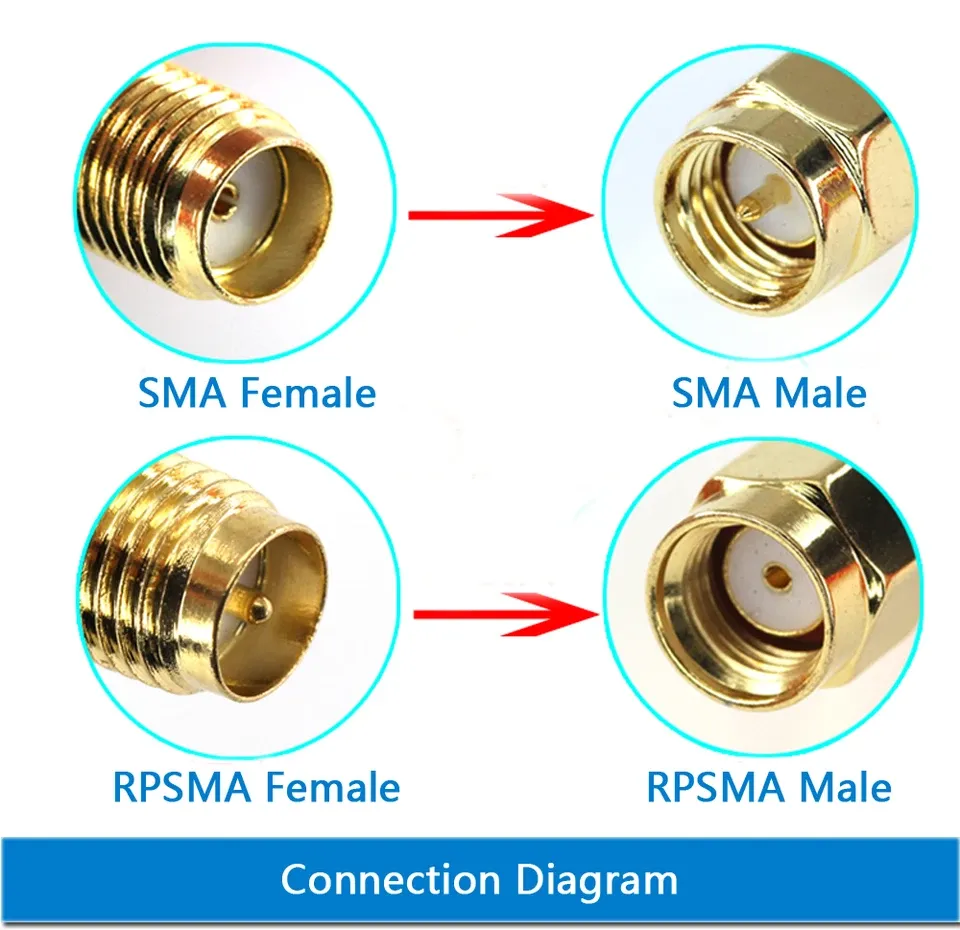

How do you pick the right connector — SMA or RP-SMA without mistakes?

The photo explains common SMA extension cable configurations: male-to-female for general use, male-to-male for specific setups, and RP-SMA for WiFi routers.

5-second pin/socket ID and common ordering traps

Quick field rule:

- SMA-male to pin inside

- RP-SMA-male to hole inside

If your module port shows a pin, it’s RP-SMA-female, so you need an RP-SMA-male antenna. We’ve seen multiple teams lose a week waiting for replacements simply because of this. When in doubt, pull up a photo-based reference like the SMA vs RP-SMA quick ID guide before submitting your PO.

Datasheets can also mislabel “plug/jack.” Always double-check the drawing or physically verify before mass ordering — procurement staff often rely on textual names alone.

Straight vs right-angle; bulkhead and bendable joints

Connector orientation isn’t just cosmetic. Straight types give the best match and lowest return loss but require headroom. Right-angle or bendable joints make sense in compact routers or gateways with limited clearance.

If your design must exit a metal wall, go for bulkhead SMA/RP-SMA versions; they seal better and allow proper torque tightening. Each variant influences strain relief, so specify it explicitly — type, angle, nut set, and torque spec — right next to gain and length in your BOM.

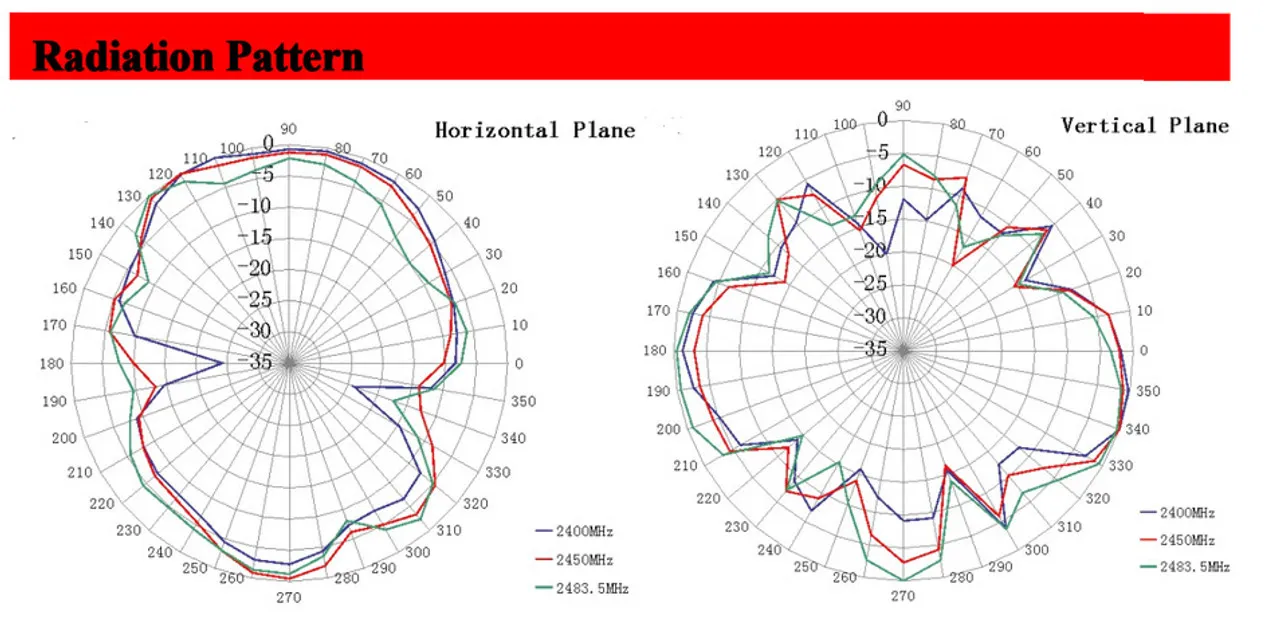

What gain do you really need — 2 dBi, 3 dBi, or 6 dBi for omni patterns?

This diagram helps engineers understand that higher gain is not always better and that trade-offs should be made based on actual coverage needs (e.g., multi-floor environments).

“Longer ≈ higher gain” trade-offs; pattern flattening & nulls

As antenna length increases, vertical lobes shrink. That’s why ceiling-mounted APs with long sticks sometimes show dead zones right beneath them. “Omni” refers to azimuth coverage only — not elevation. If your IoT nodes live on different floors, stick to 2–3 dBi.

Engineers designing mixed setups often compare elevation slices to verify null depth; the results align with what’s explained in the omnidirectional Wi-Fi antenna datasheets across vendors.

Indoor mesh vs outdoor CPE vs handheld IoT

Different use cases favor different gains:

- Indoor mesh routers: 2–3 dBi ensures vertical consistency.

- Outdoor corridor or CPE links: 5–6 dBi extends line-of-sight.

- Handheld IoT sensors: 1–2 dBi keeps efficiency without long protrusions.

Match the gain to geometry, not appearance — a visually “strong” antenna that’s too tall can sabotage multi-level coverage.

Will cable type and length quietly kill your omni link budget?

This diagram illustrates the role of pigtail cables in the RF link and the insertion loss they may introduce, emphasizing the importance of cable selection and length control.

The pigtail cable between your RF board and antenna connector often steals more signal than users realize. Short U.FL to SMA pigtails, usually built from 0.81 mm or 1.13 mm micro-coax, can lose 0.6–0.8 dB per 100 mm @ 2.4 GHz. Two connector pairs add another 0.3 dB.

That’s why many engineers now verify with a quick link-budget calculation before locking their cable length — a habit borrowed from our U.FL to SMA pigtail guide, which details typical attenuation curves for micro-coax.

Even half a dB of unexpected loss can ruin certification margin, so keep cables as short as mechanical limits allow.

Omni Link Budget Mini-Calculator

Inputs:

tx_power_dBm, gain_dBi, cable_type ∈ {0.81, 1.13}, cable_length_cm, connector_pairs, freq = 2.4 GHz, path_loss_dB, receiver_sensitivity_dBm

Typical constants:

loss_per_cm_0.81 ≈ 0.008 dB/cm @ 2.4 GHz

loss_per_cm_1.13 ≈ 0.006 dB/cm @ 2.4 GHz

connector_loss ≈ 0.15 dB per pair

Formulas:

cable_loss = loss_per_cm(type) × cable_length_cm

conn_loss = connector_pairs × 0.15

EIRP_dBm = tx_power_dBm − cable_loss − conn_loss + gain_dBi

link_margin_dB = EIRP_dBm − path_loss_dB − receiver_sensitivity_dBm

Outputs: EIRP_dBm and link_margin_dB

Rule of thumb: If link_margin < 6 dB, shorten the pigtail, reduce connector count, or move to a lower-loss cable such as RG316 (see our RG316 vs RG174 comparison for attenuation data).

Where should you place an internal omni antenna in tight enclosures?

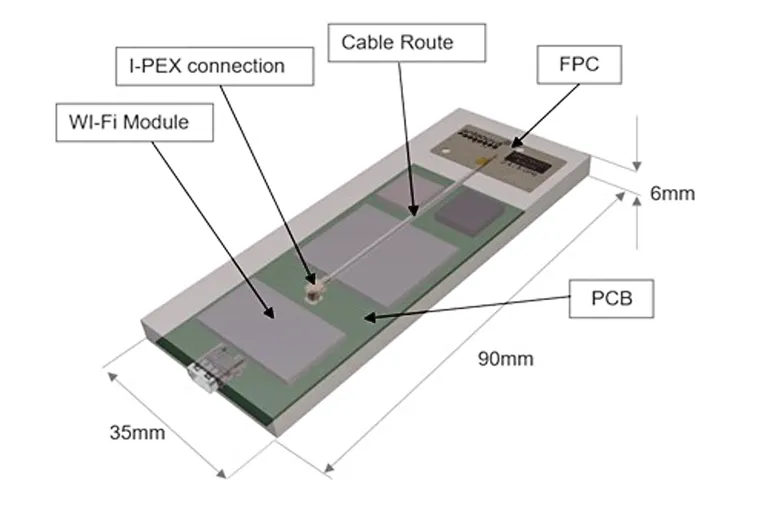

This diagram assists engineers in optimizing internal antenna placement to avoid performance degradation or detuning due to poor layout.

FPC keep-out, adhesive, ground clearance, detuning by metal

For FPC antennas, always respect the “keep-out” area marked in the datasheet — usually 5–10 mm from metal parts or ground fills. Many IoT engineers skip this when squeezing boards into housings, then wonder why range halves.

Mount the antenna with its adhesive side on the inner wall of a non-metallic enclosure, facing outward. Avoid folding or bending; even a gentle curve can shift resonance by 100 MHz.

If your enclosure uses a metal frame, create a small RF window or plastic slot. Internal antennas can still perform well if you maintain at least 3–5 mm spacing from conductive surfaces and run a short, low-loss pigtail to the main PCB. We often reference this technique when tuning small sensors — it aligns with practices shown in the SMA extension cable length and loss guide, which covers micro-coax routing best practices.

PCB/ceramic do’s & don’ts; quick A/B placement tests

For PCB traces, run a controlled impedance feed line (50 Ω) and ensure the antenna region sits clear of copper on all layers. Ceramics work best when soldered near an edge with air exposure.

A simple A/B test — flipping orientation or moving 5 mm away from a battery — often reveals a measurable 3–5 dB difference in RSSI. Keep a few prototype shells handy for tuning before finalizing mold design.

Do you actually need an outdoor omni instead of a rubber-duck?

This diagram guides the correct installation of outdoor antennas, including engineering details such as waterproofing, UV resistance, and torque control.

Mast-mount vs device-mount; IP rating, UV, and torque notes

If your antenna must sit on a pole or mast, check for IP65/IP67 ratings and UV-stabilized materials. Mounting torque matters: over-tightening SMA bulkheads can crack seals, while under-tightening causes water ingress.

A typical outdoor omni has 3–6 dBi gain and includes a short low-loss RG316 or RG58 tail. Keep it vertical; even small tilts can skew the radiation lobe. Engineers working on smart city or IIoT projects often prefer factory-sealed cable exits to avoid field assembly.

When directional beats omni (patch/Yagi) despite spec wins

Sometimes “omni” isn’t the best answer. In long corridors or outdoor point-to-point links, a directional patch or Yagi antenna can outperform any high-gain omni simply by focusing energy.

We’ve tested setups where replacing a 6 dBi omni with a 9 dBi patch doubled throughput — because most power went where it was needed. If your coverage area is linear or constrained, consider switching types; TEJTE’s RF antenna type comparisons discuss when this transition makes sense without overcomplicating BOMs.

Can you validate the omni choice with a fast field checklist?

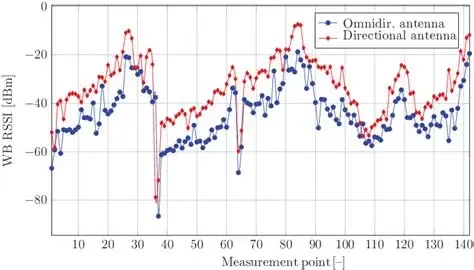

This diagram serves as a practical guide for engineers conducting quick field validation. It highlights the use of simple device rotation and RSSI monitoring to reveal nulls (blind spots) in the antenna’s vertical radiation pattern and introduces the practical technique of tilting the antenna to optimize coverage. The diagram also implies the “cable-first” troubleshooting logic.

RSSI/Throughput smoke tests; axis tilt for elevation nulls

Place your device at typical operating height and rotate it 360°. Watch RSSI drop when the antenna passes through its elevation null — that’s the blind zone directly above or below the main lobe.

If you’re integrating multiple omnis in one product, tilt one by 15–20° to smooth total coverage. Measure throughput under both line-of-sight (LOS) and obstructed conditions; anything below −70 dBm at expected range likely means excess cable loss or connector mismatch.

Cable-first fault isolation (swap order: cable to connector to antenna)

When diagnosing weak signals, start from the cable. Swap pigtails first — micro-coax wear or crimp cracks cause intermittent opens. Then check the connector pair for play or corrosion. Only replace the antenna last.

This “reverse chain” debugging approach saves time and follows the same hierarchy used in our RF coaxial cable guide: begin with the highest-loss segment, then move outward toward radiating elements.

Order like a pro: what exact SKU attributes must be on the PO?

This is not a specification table, but a specific product photo or rendering. Its purpose is to connect all the previously discussed abstract technical parameters (such as SMA male, straight/right-angle form, cable exit) with a concrete, branded physical product. It helps engineers and procurement staff visually understand “which physical attributes need to be confirmed when ordering” and may show an example of product labeling used for after-sales tracking (RMA).

Connector gender/thread, gain, length/color, bend option, temp, RoHS/REACH

A complete omni antenna SKU entry typically includes:

- Connector type & gender: SMA-male, RP-SMA-female, or IPEX/U.FL

- Gain rating: 2, 3, or 6 dBi

- Physical form: straight / right-angle / flexible

- Cable type & length: 0.81 or 1.13 mm micro-coax, 10–50 cm

- Color & material: black ABS, white fiberglass

- Mounting: bulkhead, adhesive, or mast clamp

- Compliance: RoHS, REACH, CE marking if required

When we process omni antenna orders, missing just one of these fields — like cable length — often halts the chain because connectors are pre-crimped per spec. Double-check with the Omni Ordering Matrix below before sending the PO.

| Antenna Type | Connector | Gain (dBi) | Color | Cable (Type / Length cm) | Length/Form | Mounting | IP/UV | Temp Range | Compliance | TEJTE SKU | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubber-duck (external) | SMA / RP-SMA | 2 / 3 / 6 | Black | — | Straight / Right-angle | Device-mount | - | -40 ~ +85 °C | RoHS/REACH | TA-OM-RD-SMA | DDefault Wi-Fi antenna |

| Internal FPC | IPEX / U.FL | 1-3 | Yellow film | 0.81 / 10–20 | 45×7 mm | Adhesive | - | -20 ~ +70 °C | RoHS | TA-OM-FPC-081 | Compact IoT module |

| Outdoor fiberglass | N / RP-SMA | 3-6 | White | RG316 / 30 | 20-50 cm | Mast mount | IP67 / UV | -40 ~ +85 °C | RoHS/REACH | TA-OM-FG-RG316 | Weatherproof version |

| PCB trace | Solder pad | 0-2 | Green | — | Board-integrated | PCB mount | - | -20 ~ +70 °C | RoHS | TA-OM-PCB-INT | Development boards |

What’s new for omni antennas in 2024–2025 and why it matters?

This diagram reflects antenna technology trends for 2024-2025, emphasizing the importance of multi-band integration and backward compatibility.

Wi-Fi 7 keeps 2.4 GHz coexistence; multi-link (MLO) still relies on omni coverage

Wi-Fi 7’s Multi-Link Operation (MLO) lets devices transmit simultaneously on 2.4, 5, and 6 GHz. Yet one of those links always depends on omnidirectional coverage to maintain control channels and backward compatibility. That’s why most enterprise routers still include at least one dual-band or tri-band omni whip even in next-gen platforms.

In our lab comparisons, MLO nodes that kept a dedicated 2.4 GHz omni link showed 30 – 40 % lower retry rates in mixed environments than those relying solely on directional 5 GHz beams. So even if your product claims “Wi-Fi 7-ready,” an efficient 2.4 GHz omni remains essential.

Enterprise/IIoT tri-band omni platforms & compliance reminders

This diagram reflects the design considerations for industrial-grade antennas in terms of standardization, multi-band compatibility, and compliance.

Industrial Wi-Fi and IIoT deployments are also standardizing on tri-band omnidirectional antennas, simplifying inventory. Instead of separate 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz parts, vendors integrate multi-resonant designs with 3 – 6 dBi gain across all bands.

That integration increases compliance complexity. Always verify EN 55032, RoHS 3, and REACH documentation when sourcing from multiple suppliers. TEJTE’s supply chain maintains both certificates by default — a small but crucial advantage when exporting to North America or the EU.

FAQ — omnidirectional antenna questions, answered

Does a higher-gain omni always improve indoor coverage?

How do I tell SMA from RP-SMA in under five seconds?

What’s a safe maximum length for a U.FL to SMA pigtail at 2.4 GHz?

When should I choose an outdoor omni over a rubber-duck?

Use an outdoor omni antenna whenever the unit faces weather exposure — rooftops, utility poles, or street cabinets. These antennas feature IP65/IP67 sealing, UV-stable fiberglass, and stainless brackets.

A “rubber-duck” antenna on a router might look similar but will degrade under sunlight within months. The 2.4 GHz antenna selection guide details common indoor vs outdoor breakpoints for Wi-Fi IoT deployments.

Why does my omni show weak spots directly above or below the antenna?

Can metal enclosures work with internal omnis?

Will Wi-Fi 7 make 2.4 GHz omnis obsolete?

Final takeaway

Omnidirectional antennas might look simple, but every decision — from connector type and gain to cable length and mounting — shifts your RF chain’s real-world performance. Treat them as part of the link, not an accessory.

When you’re ready to specify or order, use the calculator and ordering matrix above, verify each PO attribute, and cross-check it with your mechanical drawings.

That’s how teams avoid re-orders, stay compliant, and get the signal they actually designed for — not the one luck delivers.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.