Omni Antenna Guide: Coverage, Gain & Installation Explained

Dec 15,2025

Which omni antenna form best fits your device or site?

Serving as the opening visual guide, this image aims to dispel the misconception that there is only one form of omni antenna. It visually links three mainstream antenna forms (rubber-duck, outdoor omni, PCB/FPC) with their most suitable application scenarios (indoor IoT/Wi-Fi gear, outdoor mast mounts, inside compact devices), emphasizing the importance of selecting the correct antenna form based on the device's final usage environment and enclosure material (e.g., ABS, metal).

When engineers say “omni antenna”, they often imagine a single shape covering all directions — but that’s only half the truth. The right form depends heavily on where it lives: indoor desktop, outdoor mast, or sealed inside a gateway. Choosing wrong means mismatched gain, awkward cabling, or weeks of rework.

Rubber-duck antennas (those stubby whips on routers and handhelds) suit indoor IoT and Wi-Fi gear. They screw directly onto an SMA or RP-SMA jack and offer 2–3 dBi of gain — enough for short corridors without creating “dead cones.”

Outdoor omni antennas, by contrast, use N-type or weather-sealed SMA connectors with mast or wall mounts. They typically start at 5 dBi and go up to 12 dBi, trading beam width for distance.

Inside compact devices, engineers lean on PCB or FPC antennas, laminated or printed to save space. These internal options perform surprisingly well when paired with tuned ground clearance and RF-transparent windows.

In practice, matching the enclosure material matters as much as the antenna itself. ABS and polycarbonate housings let 2.4 GHz signals pass freely, while metal shells reflect or detune unless you leave a clear aperture. That’s why many integrators cross-reference guides like Wi-Fi Antenna Guide before committing to mechanical layouts.

How do you choose the right gain: 2–3 dBi vs 5–6 dBi vs “high-gain”?

Gain isn’t just a number on a datasheet — it’s a geometry trade-off. A 2 dBi rubber-duck spreads energy broadly, ideal for handhelds or mesh nodes where users move in every direction. A 5 dBi outdoor omni narrows its vertical beam, stretching horizontal reach across parking lots or hallways. Go beyond 8 dBi and you start carving “elevation nulls,” those thin slices above and below the antenna where the signal nearly vanishes.

From field testing, handheld radios and APs below 3 dBi maintain coverage even when tilted, while gateways on poles benefit from 5–6 dBi. High-gain sticks (9 dBi +) make sense only when you control mounting height precisely. Otherwise, the signal overshoots clients just below the beam plane.

If you’re unsure, run quick RSSI sweeps with two antennas of different gain levels before ordering bulk. A ten-minute test in your real hallway often reveals more than any spreadsheet. For readers comparing full antenna families, the overview on RF Antenna Types shows how omni units stack against panel and Yagi options.

What connector standard avoids order mistakes (SMA vs RP-SMA)?

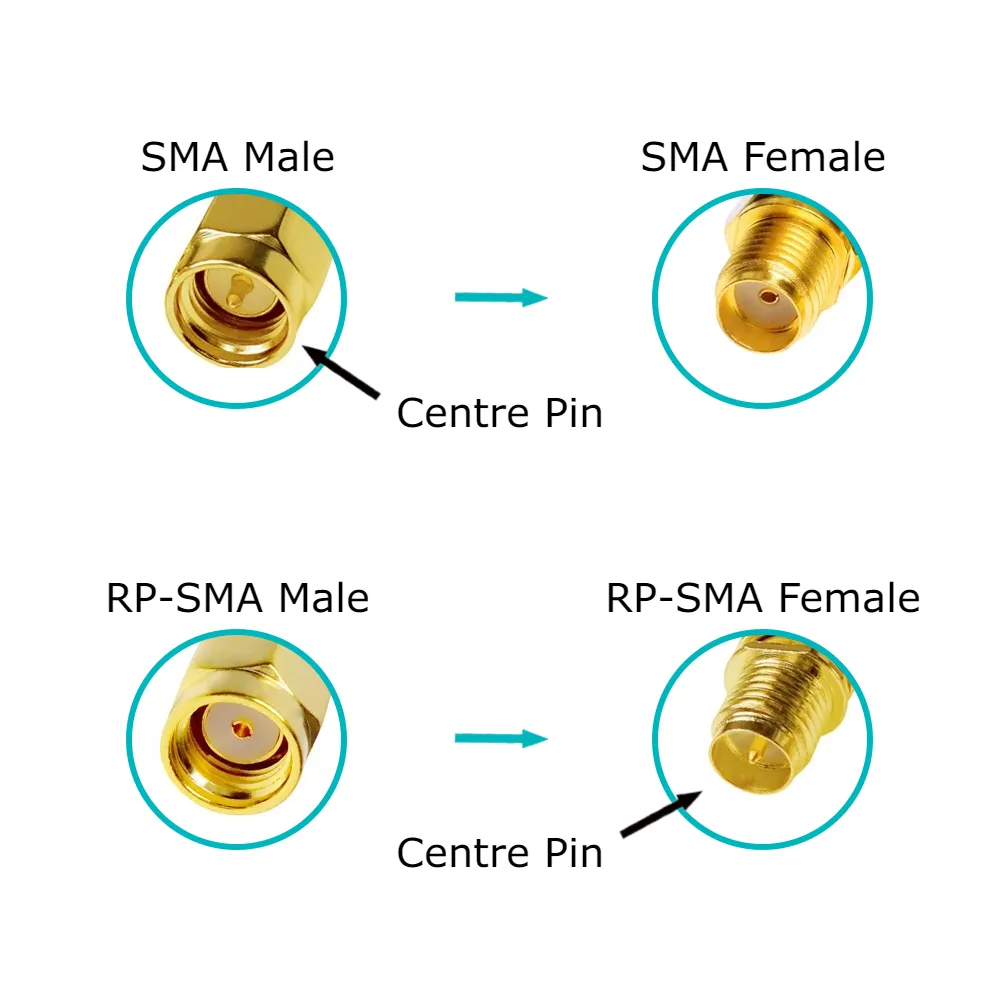

This schematic is a clear visual guide for quickly identifying and differentiating the gender and polarity of SMA and RP-SMA connectors. It compares SMA Male, SMA Female, RP-SMA Male, and RP-SMA Female side-by-side, clearly labeling their thread direction (external or internal) and the state of their center contact (with pin, with socket, hollow). This intuitive comparison is a key tool for avoiding ordering errors and interface mismatches, emphasizing the importance of checking both threads and pins.

Ask any lab engineer and you’ll hear the same confession: “I’ve ordered the wrong SMA gender more than once.” The difference looks trivial but causes days of downtime.

A simple rule:

- SMA male → has a center pin

- SMA female → has a center hole

- RP-SMA reverses that convention

Spend five seconds checking before hitting Add to Cart. Many teams mark bench gear with color bands — red for SMA, blue for RP-SMA — to prevent mix-ups during assembly. For rugged outdoor gear, choose bulkhead SMA connectors with O-rings or locknuts; they seal better and survive vibration.

You’ll also need to decide between straight and right-angle types. Straight connectors fit exposed panels, while right-angle ones tuck neatly under lids or inside enclosures. When routing multiple modules in one chassis, matching connector orientation saves both space and strain relief. TEJTE’s own Outdoor Omni Antenna Selection Guide illustrates these mechanical choices side-by-side with torque and IP-rating data.

Will cable type and length quietly erase your link budget?

| Cable Type | Diameter (mm) | Typical Loss @ 2.4 GHz (dB/m) | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.81 mm Micro-coax | 0.81 | ≈ 0.80 | Compact IoT modules, internal FPC feeds |

| 1.13 mm Micro-coax | 1.13 | ≈ 0.60 | Handhelds and routers |

| LMR-240 | 6.1 | ≈ 0.26 | Outdoor runs under 5 m |

| LMR-400 | 10.3 | ≈ 0.14 | Long mast feeds up to 15 m |

Every extra connector pair adds about 0.15 dB. So, a five-meter LMR-240 line with two pairs loses roughly 1.8 dB — small but measurable. That’s why experienced installers minimize connector chains and keep feeder lengths short.

If you’re designing a compact router where pigtails must curve sharply, use RG-178 or 1.13 mm micro-coax and validate return loss. Poor crimps or impedance mismatches can cause VSWR > 2:1, wasting nearly 10 % of transmit power. Later in this guide, we’ll introduce a mini link-budget calculator to quantify those trade-offs precisely.

Where should you mount an omni to minimize metal detuning?

This image is positioned in the key paragraph discussing mounting location. It visualizes and concretizes critical installation rules mentioned in the text, such as “maintain at least 0.25λ ground clearance” and “keep one full wavelength between antennas.” The image emphasizes that antenna mounting is not just about mechanical fixation but also part of electromagnetic environment optimization. It helps engineers preemptively avoid signal pattern distortion and link instability caused by improper installation when designing mounting brackets or planning internal device layouts.

Mounting defines whether your antenna model meets its promised specs. Place an omni near rails, parapets, or HVAC ducts, and the surrounding metal alters the field pattern. Ideally, maintain at least 0.25 λ (≈ 3 cm at 2.4 GHz) of ground clearance below the antenna base. Double that when metal masses are nearby.

Avoid lining multiple antennas side-by-side without spacing. Cross-coupling (CCI/ACI) increases noise floor and cuts link stability. A simple rule: keep one full wavelength (≈ 12.5 cm) between antennas operating on the same band.

In outdoor deployments, isolation brackets and mast offsets help maintain pattern symmetry. These mechanical tweaks often matter more than one extra dB of gain. When you evaluate mounting hardware, refer to the torque and anti-rotation recommendations in Mast Mount Antenna Brackets & Torque; it explains why certain clamps survive storms better than others.

Do you actually need an outdoor omni instead of a rubber-duck?

Many engineers default to a rubber-duck antenna simply because it’s easy — no cables, no brackets, no weatherproofing. Yet once your project leaves the lab and faces sunlight, rain, or temperature swings, the indoor convenience fades quickly.

Outdoor omni antennas exist for a reason. They’re built with UV-stabilized fiberglass or ABS shells, sealed with silicone or O-rings, and rated IP65 or higher. In coastal areas, salt-fog resistance becomes critical; even a small crack in the plating invites corrosion that detunes the feed point. For mast mounts, torque ratings matter just as much as gain. Too loose, and gusts twist the antenna off-axis; too tight, and you crush the housing or shear the threads.

Typical rule of thumb from field installations:

- ≤5 dBi units can mount on wall poles up to 3 m high;

- 6–9 dBi models prefer rigid masts with dual clamps;

- >9 dBi needs anti-rotation brackets and torque checks (≈2.5–3.0 N·m).

If your deployment involves rooftops, parking lots, or open courtyards, outdoor omnis outperform rubber-ducks tenfold in consistency. Indoor types simply can’t endure UV exposure or vibration. TEJTE’s Outdoor Omni Antenna Selection Guide lists tested models by IP grade and torque limits, making it easier to match gain to installation height.

That said, not every “bigger” antenna is better. Directional units like panels or Yagis sometimes beat omnis for point-to-point corridors. When your coverage footprint is narrow (say, a tunnel or a straight warehouse aisle), a directional beam prevents wasted radiation and boosts SNR by 3–6 dB. In mixed networks, pairing a central omni hub with peripheral directional clients often gives the best of both worlds.

Can you validate coverage fast before freezing the BOM?

Before you lock a bill of materials, it’s worth running what we call a “smoke test.” Instead of detailed link simulation, just measure RSSI and throughput in key spots using temporary mounts. These fast trials catch placement or cable-loss surprises early, saving expensive redesigns later.

Start with your intended antenna gain and cable type, then sweep across two or three tilt angles. If throughput drops sharply with only a few degrees of tilt, your gain is too high for that mounting height. Conversely, if you see stable coverage but low peak speed, check connector integrity or return loss — both can mimic “dead zones.”

A quick validation checklist engineers use in the field:

- Fix the antenna at intended height and orientation.

- Record RSSI and data rate at three distances (near, mid, far).

- Rotate the antenna ±30° to test elevation nulls.

- Swap feeders (e.g., LMR-240 vs LMR-400) to compare losses.

- Confirm VSWR < 2.0 and no visible reflection spikes.

If results differ by more than 5 dB across runs, investigate cable-first — connectors and crimps fail more often than elements. In many TEJTE lab audits, 70% of “antenna failures” came from cable impedance drift, not radiators. That’s why short, low-loss cables with proper torque are your best insurance policy.

For small-batch validation, handheld analyzers like NanoVNA or LiteVNA can confirm S11 curves up to 6 GHz. It’s a 10-minute test that tells you whether your chain — from connector to element — truly performs as specified.

How should you order like a pro so the PO is manufacturable?

Procurement errors don’t always come from finance; they start in the spec sheet. The best purchase orders read like miniature design documents, listing every mechanical and electrical trait explicitly.

Here’s how seasoned buyers and engineers structure a manufacturable PO for omni antennas.

Omni Link-Budget Mini Calculator

To avoid underperforming installations, professionals calculate their Effective Isotropic Radiated Power (EIRP) and link margin before field tests. Use these simplified formulas for quick checks:

Inputs

- tx_power_dBm (e.g., 20 dBm)

- antenna_gain_dBi (2 / 3 / 6 / 9)

- feeder_type ∈ {0.81, 1.13, LMR-240, LMR-400}

- feeder_length_m

- connector_pairs

- connector_pairs

- path_loss_dB (FSPL or measured)

Typical loss @2.4 GHz

- 0.81 mm ≈ 0.80 dB/m

- 1.13 mm ≈ 0.60 dB/m

- LMR-240 ≈ 0.26 dB/m

- LMR-400 ≈ 0.14 dB/m

- Connector ≈ 0.15 dB per pair

Formulas

feeder_loss = loss_per_m × feeder_length_m

conn_loss = connector_pairs × 0.15

EIRP_dBm = tx_power_dBm − feeder_loss − conn_loss + antenna_gain_dBi

link_margin_dB = EIRP_dBm − path_loss_dB − rx_sensitivity_dBm

Rule of thumb

If link_margin < 6 dB, improve your setup: shorten the feeder, reduce connector pairs, switch to LMR-400, or raise antenna height.

Real-World Example

Suppose you run a 2.4 GHz gateway transmitting at 20 dBm with a 6 dBi outdoor omni, connected through 5 m of LMR-240 and two connector pairs (≈ 1.8 dB total feeder loss).

Your EIRP = 20 − 1.8 + 6 = 24.2 dBm.

If the receiver sensitivity is −85 dBm and path loss is 100 dB, your link margin = 24.2 − 100 − (−85) = 9.2 dB — comfortably above the 6 dB threshold.

Had you used 1.13 mm micro-coax instead, loss jumps to ≈ 3.6 dB, cutting link margin to 7.4 dB — borderline for stable operation. These numbers explain why cable type quietly decides whether an installation passes or fails.

Engineers often embed this calculator in spreadsheets or project dashboards to simulate different antenna and cable combinations before committing to production.

Compliance and Labeling Practices

Positioned in the latter part of the guide, this summary image serves as a visual catalog, materializing the textual descriptions into physical products after all key technical parameters and selection points have been introduced. It helps engineers and procurement staff quickly grasp the diversity of products available from TEJTE, echoing the earlier “Ordering Matrix” or SKU list, and acts as a bridge connecting technical selection with final procurement decisions.

Compliance is more than paperwork; it defines shipment readiness. Every omni antenna leaving production should list:

- Gain, frequency, connector type, and IP rating on the label.

- Serial number or batch code for traceability.

- RoHS / REACH mark, proving absence of restricted substances.

During customs inspection or FCC verification, missing compliance marks can halt delivery. TEJTE’s labeling templates follow these global conventions so your goods pass export audits smoothly.

When quantities exceed 100 units, pre-printing torque or installation notes on packaging also helps technicians in the field — no manual lookup required.

What changed in 2024–2025 that affects omni deployments?

If you last evaluated omni antennas a few years ago, you might be surprised by how much has shifted — both in RF standards and mechanical design. The transition toward Wi-Fi 7 and multi-band IoT gateways has completely redefined what “standard coverage” means.

Modern routers and access points now run 2.4 GHz + 5 GHz + 6 GHz simultaneously, demanding tighter pattern control and tri-band isolation. In older omni units, wideband matching often came with poor efficiency at the edges. The latest TEJTE-style designs now use stacked dipole arrays or integrated LC matching networks that preserve 50 Ω return loss across all three bands.

Another quiet but vital update: standardized mounting hardware. By mid-2024, many OEMs shifted to universal 1-inch-14 threads and stainless mast brackets. This change means installers can reuse clamps between brands, reducing spare-part complexity and saving time on rooftops.

For IoT deployments, low-power modules still cling to 2.4 GHz because of its reach and penetration. Designers continue to prefer short, efficient omnis — usually 2 dBi FPCs or 3 dBi rubber-ducks — because every extra dB of gain demands higher current draw and tighter mechanical alignment. As one field integrator put it, “Low gain keeps devices forgiving.”

In short, the omni landscape has matured: broader frequency coverage, tougher brackets, and smarter miniaturization. Whether you’re sourcing from TEJTE or another vendor, it’s worth revisiting your antenna shortlist for these 2024-2025 improvements before your next batch order.

FAQ — Omni Antenna (Practical Buyer Questions)

Does a higher-gain omni always improve indoor coverage?

How can I tell SMA from RP-SMA on an omni antenna in under five seconds?

What’s a safe maximum length for U.FL to SMA pigtails before loss dominates?

When should I choose an outdoor omni over a rubber-duck for corridor coverage?

How much spacing should I keep from metal edges and other antennas to avoid detuning?

What torque or anti-rotation hardware prevents mast slippage in storms?

Field Recap — What Engineers Should Take Away

Designing and installing an omni antenna isn’t about blindly picking the highest gain. It’s a chain of small, precise choices:

- The form (rubber-duck, outdoor, or internal) defines where and how it radiates.

- The gain shapes the vertical beam and corridor reach.

- The connector standard ensures you can assemble and maintain it without confusion.

- The cable quietly decides how much of your transmit power actually reaches the air.

- The mounting determines if your measured performance survives real-world metal detuning.

When all these details align, your installation behaves predictably — no surprises in RSSI maps, no connector mismatches, no returns from the field.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.