MMCX Connector Guide for RF Modules and Cables

Feb 14,2026

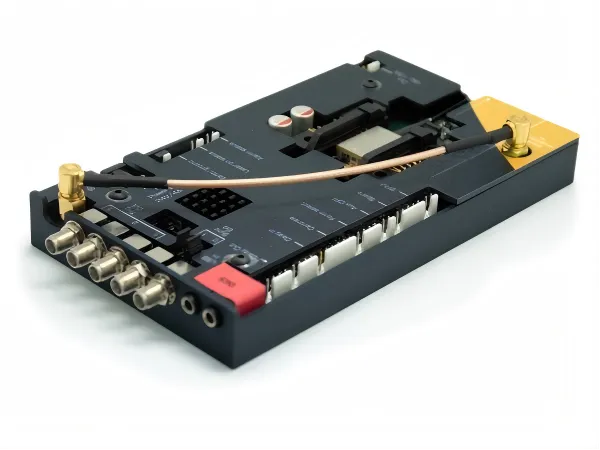

This introductory figure sets the stage for the entire guide. It likely shows a typical MMCX connector, perhaps mounted on a PCB or attached to a cable. The surrounding text explains that MMCX is often added late in the design process, after initial tests pass with lab cables. This leads to subtle problems over time—measurements change when cables are moved, return loss shifts with rotation, and setups become touch-sensitive. The image visually introduces the component that, if not treated deliberately, can quietly erode RF margin.

In many RF projects, the MMCX connector doesn’t show up in the first design review. The RF chain is already sketched out. The antenna type is chosen. Early bring-up tests pass using lab cables and adapters that “just work.”

That’s usually when MMCX gets added—quietly, and a bit late.

Nothing seems wrong at first. The link closes. Sensitivity looks fine. But over time, small inconsistencies creep in. Measurements change when the cable is touched. Rotating the connector shifts return loss. A setup that felt solid last week now needs careful handling.

Those symptoms rarely point back to active circuitry. More often, they trace to how the MMCX connector was integrated into the signal chain.

This article looks at MMCX connectors as real RF interfaces, not generic accessories. The focus is on where they sit, when they make sense, and how to choose the right form before they quietly start consuming margin.

Map where the MMCX connector sits in your RF signal chain

Before debating connector families, it helps to ask a simpler question: what is the MMCX connector actually doing in this system?

In most designs, MMCX is not the final interface. It’s a transition point.

Identify typical RF module-to-antenna paths using MMCX

A very common topology in compact RF hardware looks like this:

- RF module or radio board

- On-board MMCX connector

- Short MMCX cable or pigtail

- Panel-mounted SMA connector

- External antenna or test equipment

Electrically, every interface is nominally 50 Ω. Mechanically, they behave very differently.

The MMCX connector is usually the first flexible boundary in the chain. It sees rotation, bending, and handling long before the SMA on the panel does. That makes it a stress absorber—by design—but also a potential weak point if the rest of the system assumes it’s “invisible.”

This becomes especially clear when MMCX is paired with SMA hardware. Many engineers notice that issues attributed to the SMA side disappear when the MMCX jumper is removed from the path. That pattern shows up frequently in lab setups that rely on MMCX to SMA adapters or pigtails, a topic discussed in more detail in MMCX to SMA Adapter Choices for RF Modules.

Compare MMCX placements in IoT, GPS, and small-cell hardware

In IoT end devices, MMCX is often fully enclosed. Cable lengths are short. Power levels are modest. The connector’s role is mainly to allow flexible routing between a module and a panel feed. Here, MMCX tends to perform well as long as the cable is light and strain relief is handled elsewhere.

In GPS and GNSS equipment, the same connector sits much closer to sensitive RF stages. Return loss, phase stability, and repeatability matter more, particularly when active antennas are used. In these systems, MMCX performance is strongly tied to cable choice and launch geometry, not just the connector itself.

In small-cell or access hardware, MMCX is frequently used as an internal service interface. It enables calibration, verification, or antenna swapping without committing to threaded connectors everywhere. In that role, MMCX is rarely the limiting factor—as long as it stays within its mechanical comfort zone.

Same connector. Very different expectations.

Note recent trends in RF modules using MMCX vs U.FL

Ultra-miniature connectors such as U.FL dominate designs where the antenna cable is installed once and never touched again. MMCX continues to appear in RF modules where engineers expect repeated access during development or validation.

That distinction still influences real designs, even if it isn’t always spelled out in datasheets. MMCX survives handling better, which is why it remains common in modules intended for external antennas or configurable RF paths.

When does an MMCX connector make more sense than SMA or U.FL?

This figure provides a detailed view of an MMCX connector, likely showing its compact size and snap-interface. It is placed in the section comparing MMCX with SMA and U.FL, helping readers visually distinguish the connector. The surrounding text notes that MMCX is typically used as a transition point—often between an RF module and a panel-mounted SMA, or as an internal service interface. Its small footprint and snap-lock mechanism make it suitable for dense enclosures where space is limited but occasional access is needed.

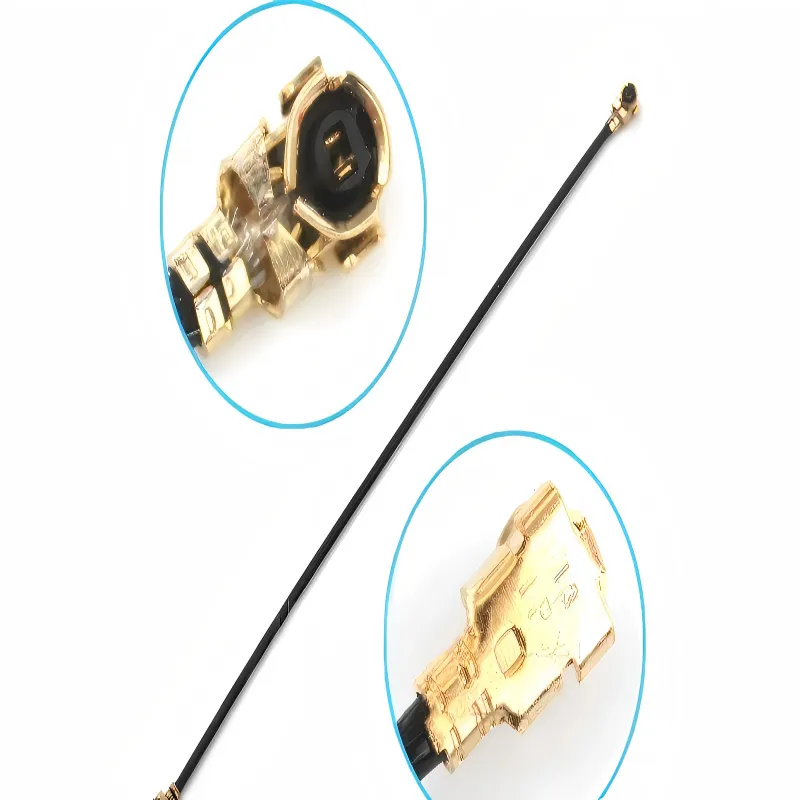

This figure shows a U.FL connector, an ultra-miniature RF interface commonly used in compact wireless devices. It is presented alongside MMCX and SMA to illustrate the trade-offs in size, mating cycles, and robustness. The guide explains that U.FL dominates designs where the antenna cable is installed once and never touched again, while MMCX is preferred when repeated access during development or validation is expected. The image visually reinforces the size comparison, helping designers choose the right connector for their access requirements.

This figure displays an SMA connector, the threaded RF interface ubiquitous in test equipment, antennas, and modules. It is shown in contrast to MMCX and U.FL to highlight differences in mechanical robustness, mating cycle tolerance, and size. The guide emphasizes that while SMA handles torque well and provides a rugged connection, it requires more space and assembly effort. The image serves as a visual benchmark for the more compact MMCX connector.

Weigh size, frequency, and mating cycle requirements

Compared with SMA, MMCX saves space and eliminates threaded mating. There’s no torque spec to manage, no risk of cross-threading, and no wrench required. That’s valuable in dense enclosures or fast-moving lab environments.

Compared with U.FL, MMCX tolerates more mating cycles and less careful handling. Engineers are more willing to unplug and reconnect it during tuning, which matters during long development cycles.

From a frequency standpoint, MMCX is rarely the bottleneck in sub-6 GHz systems. Layout quality and cable loss dominate long before the connector itself does—especially when paired with cables like RG316 or similar assemblies discussed in RG316 Coaxial Cable Specs, Loss & Uses.

Decide based on enclosure access and field service needs

MMCX works best when it lives inside the enclosure, protected from heavy cables and external loads. It’s a good fit when occasional access is needed but a full SMA implementation would be unnecessary or bulky.

If the connector must be exposed, weather-sealed, or support mechanical load, MMCX is not the right choice. In those cases, SMA connectors—covered in detail in SMA Connector Selection for RF Cables and Antennas—remain the safer option.

Avoid common overkill or misuse scenarios with MMCX

Two misuse patterns appear repeatedly in field failures. The first is using MMCX in high-power RF paths, where its small contact area limits thermal margin. The second is exposing MMCX as an external antenna interface without proper strain relief.

Both cases tend to produce intermittent, hard-to-reproduce issues. They’re often blamed on cables or antennas, but the root cause is simply pushing MMCX beyond the role it was designed for.

How should you choose MMCX connector gender, orientation, and mounting style?

Select plug vs jack based on module vs cable roles

In most RF systems, the PCB carries the MMCX jack, while the cable carries the plug. This keeps wear on the replaceable component and reduces the risk of PCB damage during servicing or repeated testing.

Reversing this arrangement rarely improves performance and often complicates rework.

Choose right-angle vs straight MMCX for tight layouts

Right-angle MMCX connectors save height, but they introduce sharper impedance transitions and greater mechanical leverage on solder joints. Straight connectors usually offer cleaner RF launches and better durability—provided the enclosure allows the extra height.

When right-angle parts are unavoidable, careful pad geometry and ground continuity become more important than the connector style itself.

Compare PCB edge-mount, surface-mount, and bulkhead MMCX

This figure shows a surface-mount MMCX connector soldered onto a PCB. It appears in the section discussing mounting styles, alongside edge-mount and bulkhead options. The guide notes that surface-mount MMCX connectors are compact and cost-effective, but sensitive to solder quality. The image helps engineers visualize this common attachment method and understand its trade-offs in terms of mechanical stability and RF launch quality.

This figure likely illustrates an edge-mount MMCX connector, a common alternative to surface-mount versions. Based on the surrounding text discussing PCB edge-mount, surface-mount, and bulkhead options, this image probably shows the edge-mount variant. The guide mentions that edge-mount versions provide a cleaner RF transition and stronger mechanical anchoring compared to SMT. The image helps designers compare mounting styles and choose the one that best fits their layout and performance requirements.

Surface-mount MMCX connectors are compact and cost-effective, but sensitive to solder quality. Edge-mount versions provide a cleaner RF transition and stronger mechanical anchoring. Bulkhead styles are useful when the connector must pass through an internal shield or panel.

Each option trades assembly simplicity for RF and mechanical margin. The best choice depends less on datasheet numbers and more on how the product will actually be assembled, handled, and serviced.

How do you pair the MMCX connector with the right RF cable?

Most MMCX-related problems don’t start at the connector. They start one step away, at the cable.

MMCX is small, tolerant of rotation, and easy to mate. Those traits make it attractive. They also make it unforgiving when paired with the wrong cable geometry, stiffness, or loss profile. Once the cable is wrong, no amount of connector swapping fixes the behavior.

Match MMCX connector families to cable outer diameter

MMCX connectors are not universal with respect to cable size. Each crimp or solder style is designed around a narrow outer-diameter window. Forcing a mismatch usually “works” at first and fails later.

Common, proven pairings include:

- 1.13 mm / 1.32 mm micro-coax for extremely tight internal routing

- RG178 when flexibility is critical and loss budget is forgiving

- RG316 coaxial cable when shielding, durability, and repeatability matter

RG316 is often chosen not because it is the lowest-loss option, but because it behaves consistently across handling, temperature changes, and repeated bending. That tradeoff is explained in more detail in RG316 Coaxial Cable Specs, Loss & Uses, which many teams reference when deciding whether micro-coax is “too small” for their application.

Cable diameter also affects pull force. A thin cable places more stress on the MMCX snap interface during handling, while a thicker cable transfers more load unless strain relief is added.

Plan MMCX cable choices for RG316, micro-coax, and semi-rigid

Each cable class changes how the MMCX connector behaves in the system.

Micro-coax keeps layouts compact, but loss rises quickly with frequency and length. It also tends to fail internally before the connector shows visible damage.

RG316 cable sits in a practical middle ground. Loss is moderate, shielding is strong, and mechanical behavior is predictable. For short internal jumpers, it’s often the least surprising choice.

Semi-rigid cable provides excellent electrical stability but transfers mechanical stress directly into the connector and PCB. When paired with MMCX, it should be treated as a fixed assembly, not a serviceable link.

These differences are rooted in coaxial construction fundamentals rather than connector choice. If you need a refresher on why cable geometry dominates RF behavior, the background in Coaxial cable basics is still one of the clearer neutral references.

MMCX connector + cable selection matrix

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Application_scenario | IoT module / GPS receiver / small cell / test jumper |

| f_max_GHz | Maximum operating frequency |

| P_max_dBm | Maximum RF power |

| Cable_type | RG316 / RG178 / 1.13 mm micro-coax / semi-rigid |

| Cable_OD_mm | Cable outer diameter |

| MMCX_mount_style | SMT / edge-mount / bulkhead |

| Required_flex_cycles | Expected bending cycles |

| Pull_force_req_N | Required pull-out resistance |

| Loss_budget_dB | Allowable link loss |

| Recommended_combo | Suggested MMCX + cable pairing |

Cable loss estimate

Cable_Loss_dB ≈ α(f) × L_m

Where α(f) is the frequency-dependent loss per meter for the chosen cable.

Total link loss estimate

Total_Loss_dB ≈ Cable_Loss_dB + N_connectors × 0.1

The 0.1 dB per MMCX connection is a conservative planning value, not a guaranteed number. If the estimated total exceeds the loss budget, the options are limited: shorten the cable, reduce connector count, or move to a lower-loss cable.

How can you control RF loss and VSWR around MMCX transitions?

Estimate insertion loss from MMCX plus RG316 jumpers

A short MMCX jumper made from RG316 usually contributes a few tenths of a dB of insertion loss. On its own, that seems trivial.

The issue appears when multiple transitions accumulate: MMCX on the module, MMCX to SMA cable, SMA to SMA test lead, then another adapter at the instrument. Each interface looks acceptable in isolation. Together, they explain why measured performance rarely matches simulations.

This is one reason experienced engineers minimize transitions in critical paths, especially when using mmcx to sma adapter chains during lab work. Practical guidance on choosing between rigid adapters and flexible assemblies is covered in MMCX to SMA Adapter Choices for RF Modules.

Keep return loss under control at module and cable ends

Return loss issues around MMCX are often blamed on the connector, but the real causes are usually nearby:

- Abrupt impedance changes at the PCB launch

- Incomplete ground reference near the pad

- Cable shield termination that isn’t electrically tight

A clean transition from controlled-impedance trace into the MMCX footprint matters more than connector brand. Small geometric errors create reflections that look like connector problems during troubleshooting.

Validate VSWR targets with simple bench measurements

You don’t need an elaborate setup. A calibrated VNA, a known-good reference cable, and controlled mating pressure reveal most MMCX-related issues quickly.

If VSWR shifts noticeably when the cable rotates, that’s a mechanical signal integrity problem—not a tuning issue.

How do you design MMCX connectors for mechanical retention and durability?

Understand MMCX snap-lock and 360° rotation behavior

The snap-lock interface allows fast mating and full rotation. Rotation helps relieve cable twist, but it also means retention depends entirely on spring force and contact geometry.

Once that interface wears, the connector still mates—but no longer holds consistently.

Set pull-force and torque limits for your hardware

MMCX connectors should not be asked to support cable weight or repeated pulling. Strain relief belongs elsewhere: adhesive anchors, clips, or cable routing features in the enclosure.

Design teams that define explicit pull-force limits early tend to see fewer intermittent failures later.

Qualify vibration and shock for field and automotive uses

In environments with vibration or shock, MMCX requires support. Without it, the snap interface loosens over time, even if electrical specs look fine on paper.

For systems that must survive these conditions, many engineers reconsider whether MMCX is appropriate—or treat it strictly as an internal, non-serviceable interface.

Guidance on connector robustness across RF families is often summarized in broader standards discussions such as RF coaxial connector standards, which help frame where MMCX fits relative to threaded connectors like SMA.

How should you route PCB traces into an MMCX connector footprint?

Keep controlled-impedance microstrip or stripline into the pad

The goal is not perfection. It’s continuity.

A controlled-impedance trace should arrive at the MMCX pad without abrupt width changes or unexplained geometry shifts. Sudden neck-downs, last-minute width changes, or ad-hoc pad edits introduce reflections that look like connector defects during measurement.

In practice, the cleanest launches come from footprints that treat the connector pad as an extension of the transmission line, not a termination. This is especially important when MMCX is paired with low-loss cables such as RG316, where connector transitions become more visible in S-parameter data.

Avoid stubs, via fields, and ground voids near MMCX

Stubs near MMCX footprints are common. Test vias, unused pads, or “just-in-case” probe points create short resonators that shift with frequency.

Ground discontinuities are even more damaging. Partial ground pours, voids under the connector body, or poorly stitched reference planes break the return path. The resulting mismatch is often misdiagnosed as a bad MMCX cable.

If you need a neutral reference on why these effects occur, the transmission-line behavior described in Coaxial cable basics applies just as much to PCB launches as it does to cables.

Design solder mask openings and paste for assembly robustness

MMCX connectors are small, but they are not tolerant of floating. Excess solder lifts the connector and changes pad geometry. Too little solder weakens joints and accelerates fatigue.

This is one area where working closely with the assembler pays off. Footprints that look fine in CAD often behave differently on the line.

How can you use MMCX to SMA adapters and pigtails without killing margin?

This figure depicts a complete cable assembly: an SMA female connector on one end, an MMCX male on the other, joined by RG316 coaxial cable. It is placed in the section discussing adapters and pigtails. The guide contrasts rigid adapters with flexible cable assemblies, noting that flexible assemblies are usually safer for repeated testing as they decouple mechanical stress from the MMCX jack. The image provides a clear visual of this practical component, helping engineers decide when to use an adapter versus a full cable for their test setups or internal connections.

Choose MMCX to SMA adapters vs MMCX cables in the lab

Rigid MMCX to SMA adapters are convenient when space allows and measurements are brief. They reduce cable clutter and simplify setups.

Flexible MMCX to SMA cable assemblies are usually safer for repeated testing. They decouple mechanical stress from the MMCX jack and reduce the chance of rotation-induced variation.

Teams that rely heavily on adapters often rediscover this distinction after chasing inconsistent lab data. The tradeoffs are discussed in more detail in MMCX to SMA Adapter Choices for RF Modules, which many engineers reference when standardizing test setups.

Limit the number of MMCX–SMA transitions in critical paths

Every transition costs margin. That margin loss isn’t dramatic—but it adds up.

A practical rule used in many labs: if a critical RF path includes more than two connector family transitions, it deserves a second look. Removing even one adapter often improves repeatability more than retuning the circuit.

This becomes especially relevant when MMCX paths interface with threaded connectors such as SMA, which are covered extensively in SMA Connector Selection for RF Cables and Antennas.

Document adapter chains in test setups and production jigs

Undocumented adapters are invisible sources of loss. When results don’t line up between benches or between lab and production, the missing piece is often an adapter no one wrote down.

Treat adapters as BOM items, not temporary conveniences.

How do you verify MMCX connector designs before and after production?

Build a quick bring-up checklist for new MMCX designs

A simple checklist catches most problems early:

- Visual inspection of pad and solder quality

- Gentle pull and rotation check on the cable

- Baseline insertion loss and return loss measurement

- Repeat measurement after re-mating

If numbers move after re-mating, the issue is mechanical, not electrical.

Use A/B cable and connector swaps to isolate failures

Swapping a known-good MMCX cable is one of the fastest ways to isolate issues. If performance follows the cable, the problem isn’t on the board. If it doesn’t, the PCB launch deserves scrutiny.

This approach often saves hours compared to probing or simulation.

Track field returns and lab measurements as feedback

Over time, patterns emerge. Certain cable types fail first. Certain footprints behave better. Teams that log these observations build informal—but extremely valuable—design rules.

Those rules tend to matter more than datasheet numbers.

How to troubleshoot common MMCX connector issues in RF modules?

Fix intermittent connections and rotation-sensitive failures

Rotation-sensitive dropouts almost always point to mechanical wear: weakened snap-lock force, damaged cable center conductors, or cracked solder joints at the PCB launch.

The fastest check is controlled rotation while monitoring return loss. If S11 moves with rotation, the interface is no longer stable.

Address VSWR spikes and unexpected loss at MMCX ports

Start at the launch, not the connector body. Look for ground discontinuities, solder voids, or pad deformation. Then check the cable termination. Only after those are ruled out should the connector itself be suspect.

Understanding how connector standards define acceptable behavior can help set expectations; summaries such as RF coaxial connector standards provide useful context when comparing MMCX to threaded alternatives.

Deal with damaged jacks and plugs in the field

MMCX jacks are not meant to be repaired in place. If damage is confirmed, replacement is usually the only reliable option.

Field strategies that work best involve stocking spare cable assemblies and minimizing direct handling of board-mounted connectors.

FAQ

How many mating cycles can a typical MMCX connector handle before reliability drops?

Most MMCX connectors are rated for several hundred mating cycles. In practice, performance degrades sooner if cables are rotated under load or pulled without strain relief. Labs that expect frequent re-mating often derate this number significantly.

Is an MMCX connector robust enough for outdoor or high-vibration environments?

Only with support. Without strain relief or mechanical damping, vibration loosens the snap interface over time. In harsh environments, MMCX is best treated as an internal link rather than an exposed connector.

Can I mix MMCX cables and connectors from different vendors in the same RF system?

Mechanically, many combinations fit. Electrically and mechanically, tolerances vary. Mixing vendors increases variability and should be validated explicitly.

What should I check first if rotating the MMCX cable causes signal dropouts?

Start with the connector interface. Check snap retention, cable center continuity, and solder joints at the PCB launch before adjusting tuning or firmware.

How do I choose between an MMCX to SMA adapter and a full MMCX to SMA cable assembly?

Adapters are compact and convenient. Cable assemblies reduce stress and improve repeatability. For repeated testing, cables usually age better.

What VSWR and insertion loss targets are realistic for an MMCX-based RF link at 2.4 GHz?

VSWR below 1.5 and insertion loss consistent with cable length and connector count are realistic targets. Deviations usually indicate launch or termination issues rather than connector limits.

How can I spot counterfeit or substandard MMCX connectors in the supply chain?

Watch for inconsistent plating, weak snap force, vague datasheets, and missing mechanical ratings. These issues often show up as variability rather than outright failure.

Closing note

MMCX connectors rarely fail loudly. They fail quietly—by shaving margin, introducing variability, and turning solid links into fragile ones. When treated as a designed interface rather than a convenient afterthought, MMCX behaves predictably and earns its place in compact RF systems.

That difference is not about the connector itself. It’s about how deliberately it’s used.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.