MMCX Cable Guide for RF Modules and SMA Transitions

Jan 14,2025

This opening graphic sets the stage by highlighting a common oversight in RF design. It likely depicts an MMCX connector or cable in a subtle or background position within a complex electronic product, symbolizing how this small, passive component is often considered harmless and specified only after major components (like RF modules and antennas) are finalized, potentially leading to late-stage issues.

In most RF hardware projects, the mmcx cable isn’t discussed early.

Not because it’s unimportant—but because it looks harmless.

It’s passive. It’s small. And it usually gets specified after the RF module, antenna strategy, and enclosure layout already feel “good enough.” By that point, attention has moved on.

That sequencing is exactly why MMCX-related issues tend to surface late.

On the bench, everything works. Sensitivity looks acceptable. The link closes. Then the cable gets rerouted, an adapter is added for convenience, or the enclosure is finally closed—and the margin shifts just enough to raise questions.

In many of those cases, the problem isn’t the RF IC or the antenna design. Both are doing exactly what they did before. What changed is how the mmcx connector and cable assembly now sit between the module and the real antenna interface.

This article stays focused on those moments. Not connector marketing. Not textbook theory. Just how mmcx cable assemblies behave once a design leaves the schematic and starts behaving like a product—and how to choose them without creating RF or mechanical risk that only shows up when it’s expensive to fix.

How do you integrate mmcx cable between RF modules and real antennas?

Map the typical RF path when an mmcx connector lives on the PCB

This diagram provides a visual breakdown of a common RF architecture in compact devices. It likely shows sequential blocks or icons representing the RF chipset, an MMCX connector soldered to the PCB, a short MMCX cable, and finally an external antenna or test port. It illustrates how the MMCX interface introduces flexibility (and potential discontinuities) between the fixed board and the variable external world.

In compact wireless designs, the RF signal path often looks deceptively simple:

RF chipset or module → on-board MMCX connector → mmcx cable → external interface → antenna or test equipment

That external interface might be an SMA bulkhead on a plastic enclosure, a temporary lab port, or a cabled antenna mounted away from the PCB. This topology is common in GPS receivers, cellular and LoRa modules, Wi-Fi cards, and compact gateways where the RF module is buried inside the product but the antenna must remain flexible.

The appeal of the mmcx connector is clear. It’s small, snap-on, and allows rotation, which reduces torque during assembly. That rotational freedom matters when cables are routed through tight mechanical paths or when the enclosure tolerances are not perfectly controlled.

What often gets overlooked is that once MMCX enters the path, you’ve introduced two additional RF discontinuities—one at the board interface and one at the cable transition. At lower frequencies, this is rarely noticeable. At higher bands, it can quietly dominate the loss budget.

For teams that want to separate connector mechanics from cable behavior, it helps to treat them as distinct design layers. Many engineers do this by first locking down MMCX interface rules using a connector-focused reference, then handling cable selection independently. The broader structure and variants of MMCX interfaces are already covered in TEJTE’s existing connector content, so this article stays focused on the cable side.

Compare mmcx cable to u.FL leads and direct-solder pigtails in compact layouts

This product photo serves as a direct comparison point within the guide. It shows a U.FL jumper cable, which is even smaller than MMCX and commonly used in space-constrained designs like ultra-thin laptops or modules. The guide contrasts it with MMCX, noting U.FL's advantages in size and cost but drawbacks in limited mating cycles and durability during rework.

MMCX is rarely the only option on the table. In practice, it’s usually compared against u.FL leads or soldered pigtails.

- u.FL jump leads are extremely compact and cost-effective. They work well in very thin devices but offer limited mating cycles and are easy to damage during rework.

- Direct-solder pigtails eliminate one connector interface entirely. Electrically clean, but unforgiving when a board needs to be replaced or serviced.

- mmcx cable assemblies sit in between. They are larger than u.FL, but far more tolerant of rotation and repeated connect/disconnect.

In products that will be opened, debugged, or revised across multiple SKUs, MMCX often proves more forgiving over time. In sealed consumer devices that are never serviced, smaller options may still be acceptable.

There is no universal “best” answer here. The real tradeoff is between mechanical robustness and absolute compactness.

Identify when mmcx cable becomes the weakest link in your RF budget

At sub-1 GHz, MMCX-related losses are rarely the limiting factor. Systems are forgiving, and margins are usually wide enough to absorb small inefficiencies.

At 2.4 GHz, 5 GHz, or GNSS bands, the story changes. Cable attenuation and connector return loss start to stack. Each element looks minor in isolation, but together they can quietly consume several decibels of margin.

This is why MMCX issues often surface late in validation. A system that “worked fine” during early testing suddenly shows unstable throughput or reduced range once routing changes or the enclosure is finalized. The mmcx cable didn’t fail—it simply became the dominant loss contributor after everything else was optimized.

How should you choose between different mmcx cable and connector combinations?

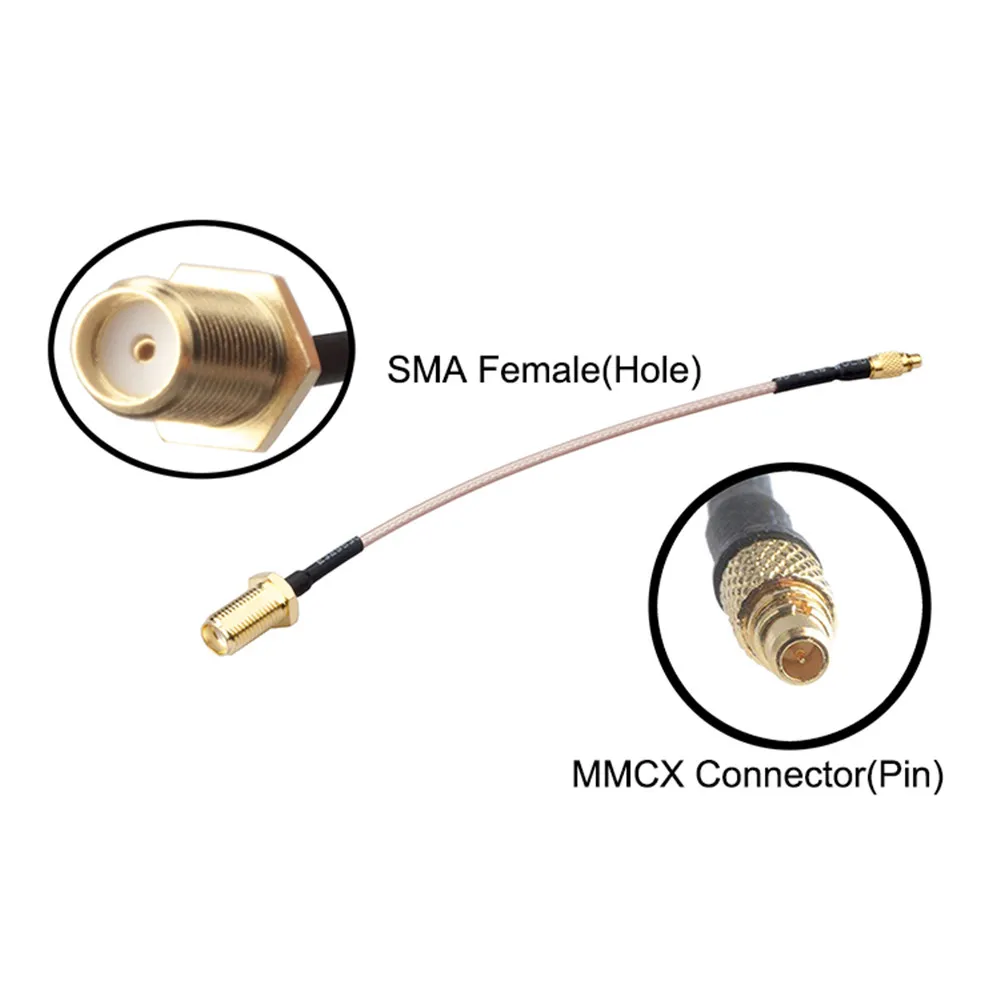

Separate MMCX to MMCX, MMCX to SMA, and other transition styles by use case

This image likely displays a selection of physical MMCX cable assemblies with different terminations. It visually categorizes them by their end connectors: MMCX-to-MMCX for internal board-to-board jumps, MMCX-to-SMA for transitioning to a more robust external interface, and perhaps others like MMCX-to-RP-SMA. The image supports the guide's discussion on choosing the right transition style based on where flexibility is needed in the system.

Not all MMCX transitions serve the same purpose, even if they look similar on a BOM.

- MMCX to MMCX assemblies are typically used as short internal jumpers between boards or RF modules.

- MMCX to SMA connector cables are common when the PCB exposes MMCX but the enclosure standardizes on SMA for antennas or test access.

- MMCX to instrument paths often involve an additional conversion step before reaching BNC or N-type ports in lab environments.

The real decision is where you want flexibility. A single integrated mmcx to sma connector cable minimizes interfaces and loss. A modular chain—MMCX cable plus a separate mmcx to sma adapter—is easier to reconfigure during development and troubleshooting.

Both approaches are valid. They simply optimize for different phases of a product’s lifecycle.

Match mmcx cable to RG174, RG316, and micro-coax families by diameter and loss

| Cable type | Outer diameter |

|---|---|

| 1.13 | 1.13 mm |

| 1.32 | 1.32 mm |

| 1.37 | 1.37 mm |

| Flexible .047" | 1.42 mm |

| RG178 | 1.80 mm |

| RG405 (.085") | 2.15 mm |

| RG316 | 2.48 mm |

| Flexible .085" | 2.64 mm |

| RG174 | 2.80 mm |

| RG316 Double Braid | 2.90 mm |

| RG402 (.141") | 3.58 mm |

| RG58, RG142, Low Loss 195 | 4.95 mm |

| Cable family | Typical diameter | Relative loss | Common applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Micro-coax | < 2 mm | Highest | Very short internal runs |

| RG174 | ~ 2.8 mm | Medium | GPS, short cellular links |

| RG316 | ~ 2.5 mm | Lower | Automotive, higher-temperature environments |

In theory, thinner cable always makes routing easier. In practice, many teams default to RG316 even when it feels oversized. Its PTFE dielectric handles heat, vibration, and long-term aging more gracefully. Engineers who have dealt with cable stiffening or drift after thermal cycling tend to be conservative here.

If you need broader attenuation context across coax families commonly paired with MMCX, TEJTE’s RG cable guide provides a useful comparison baseline without focusing on any single connector type.

MCX Cable Transition Decision Matrix

This diagram presents a practical engineering tool. It is likely a table or flowchart that takes basic parameters (e.g., board interface, external interface, frequency band, cable length, environment) and outputs a recommended MMCX cable strategy or flags potential risks. The guide emphasizes its role in bringing consistency and repeatability to decision-making, preventing late-stage workarounds by applying conservative thresholds.

When MMCX decisions go wrong, it’s rarely because the connector itself was misunderstood.

More often, several small choices—frequency, length, environment, interface—were made independently. Each decision looked reasonable in isolation. Together, they pushed the RF path into a corner.

That’s usually when a transition matrix appears.

Not at the start of a project—but after the third or fourth design review, when the same questions keep coming back.

The goal isn’t precision math. It’s consistency.

A simple MMCX Cable Transition Decision Matrix helps teams rule out risky combinations early, before they turn into late-stage workarounds. It’s not a simulator. It’s a filter.

The inputs are intentionally basic: what interface is on the board, what lives outside the enclosure, which band you’re operating in, how long the cable needs to be, and what kind of environment the product will see.

Instead of calculating insertion loss every time, the matrix applies conservative thresholds. They aren’t perfect, but they’re repeatable. And repeatability is usually what teams are missing.

For example, once cable length creeps past half a meter at 5–6 GHz, experience says the risk profile changes. Not always enough to fail—but enough that MMCX stops being the right place to carry loss. That’s when the strategy shifts toward shorter MMCX sections and thicker feeders downstream.

Most RF labs and production lines already follow this logic informally. Writing it down simply makes the decision explicit—and easier to defend when tradeoffs are questioned later.

How can you estimate electrical limits for mmcx cable runs without overcomplicating the math?

Use basic 50 ohm and DC–6 GHz specs as guardrails

Most mmcx connector systems are specified as 50 Ω and typically rated up to 6 GHz. That spec defines compatibility, not guaranteed performance.

The impedance standard itself comes from long-established RF practice, and the concept of 50 ohm transmission lines is well documented in foundational RF references such as the general overview of coaxial cable. What matters in practice is how close your real assembly stays to that ideal once connectors, bends, and adapters are introduced.

Voltage ratings are rarely the limiting factor in RF modules. In low-power systems, loss and reflection dominate long before breakdown becomes a concern.

Translate vendor attenuation curves into “safe length” rules of thumb

Instead of memorizing datasheets, many engineers rely on quick heuristics derived from attenuation curves:

- At 2.4 GHz, thin coax often loses roughly 0.2–0.3 dB per 10 cm

- At 5 GHz, that number increases sharply, especially for micro-coax

These values are not universal, but they’re close enough to flag trouble. If your link budget only has a few decibels to spare, even modest increases in mmcx cable length can matter.

The underlying reason is straightforward RF physics: conductor loss rises with frequency, and dielectric loss compounds it. This frequency-dependent behavior is discussed broadly in RF transmission theory and summarized in many educational resources, including high-level treatments of radio-frequency engineering.

Decide when mmcx cable should hand off to a thicker RF feeder

Once cable length exceeds roughly 1 m at ≥5 GHz, many designs benefit from a hand-off. A short MMCX pigtail transitions to a thicker, lower-loss feeder using SMA or N-type connectors.

This is not about “MMCX being bad.” It’s about choosing the right interface for each segment of the RF path. MMCX excels at board-level flexibility. Larger connectors excel at longer runs.

If you’ve ever watched a marginal link stabilize simply by shortening the MMCX section and moving the loss downstream, the pattern becomes obvious.

How do you keep mmcx cable mechanically reliable inside dense hardware?

This instructional image focuses on mechanical reliability. It likely contrasts a gentle, sweeping bend (correct) with a sharp kink or 90-degree bend right at the MMCX connector (incorrect). The guide warns that excessive bending near the termination can degrade electrical performance and mechanical integrity over time, leading to failures often misattributed to connector quality.

Respect bend radius and avoid hard corners on miniature coax

Miniature coaxial cable does not fail loudly. It degrades quietly.

Excessive bending near the MMCX termination can change impedance, damage the dielectric, or weaken the shield over time. These effects rarely show up immediately. They appear after thermal cycling, vibration, or repeated enclosure assembly.

Most failures attributed to “connector quality” are actually routing failures.

Place strain relief and tie-down points early in the layout

The rotational freedom of an mmcx connector helps during assembly, but it does not protect against peel forces. A small tie-down point, clip, or channel that transfers load from the connector to the cable jacket can dramatically extend service life.

This is especially important in automotive and industrial products where vibration is continuous rather than occasional.

Route mmcx cable away from heat and noisy power structures

Routing MMCX lines near DC-DC converters, power inductors, or motor drivers introduces two risks at once: thermal aging and EMI coupling.

Even when coupling does not cause outright failure, it can add just enough noise or drift to complicate debugging later. Separation, shielding, or grounded partitions are often simpler than chasing unexplained RF variance during certification.

When should you convert from mmcx cable to SMA and other external connectors?

Choosing between integrated mmcx to sma connector cables and adapter chains

Once the RF path leaves the PCB, MMCX usually stops being the “main” connector.

The question becomes how quickly you want to transition out of it.

In practice, there are two patterns that show up again and again.

The first is a single, integrated mmcx to sma connector cable. One assembly. One transition. Fewer variables.

Electrically, this is the cleaner option. Fewer interfaces mean fewer places for mismatch to hide.

The second pattern is modular: a short mmcx cable, then a separate mmcx to sma adapter, then a standard SMA cable.

This looks messier on paper, but it survives lab life better. Instruments change. Antennas change. Cable lengths change. Adapters make that friction smaller.

Most teams end up using both—modular chains during development, integrated assemblies once the design hardens. That split is not accidental. It reflects how RF products actually evolve.

Understanding what adapter stacking really costs you

Adapter stacks rarely break systems outright. They blur them.

At low frequencies, you can stack MMCX → SMA → BNC and never notice. At higher bands, especially above 3 GHz, the accumulated reflection starts to matter. Not enough to scream “failure,” but enough to shift readings.

That’s where confusion starts. Engineers re-tune antennas. They second-guess the RF module. They re-route ground pours.

Meanwhile, the test chain itself is the variable.

When measurements feel inconsistent, simplifying the path is often the fastest diagnostic. Swapping an adapter chain for a single mmcx to sma connector cable removes several unknowns in one step.

Planning panel interfaces so future changes don’t hurt

This is a specific product photo of a hybrid cable assembly. It represents a key design pattern recommended in the guide: using an integrated MMCX-to-SMA cable to transition from the flexible, board-level MMCX interface to a more robust, standardized SMA interface at the enclosure panel. This approach locks the stable boundary at the panel while keeping MMCX's flexibility internal.

A common mistake is treating the panel connector as an afterthought.

If the enclosure exposes MMCX directly, you’ve locked that interface forever. Changing antennas later becomes awkward. Changing cable families becomes harder. Field replacements get riskier.

This is why many designs intentionally convert from mmcx cable to SMA at the panel, even if the run is short. MMCX stays internal, where it excels at flexibility. SMA becomes the stable boundary.

That separation pays off when SKUs multiply or frequency variants appear. You change cables. You don’t change boards.

How are recent market trends changing how engineers use mmcx cable?

MMCX is no longer treated as “temporary”

A decade ago, MMCX was often used as a convenient internal jumper. Something you might replace later with a soldered joint or a different connector.

That mindset is fading.

As RF modules become denser and enclosure constraints tighten, mmcx connector interfaces are increasingly designed in from the start. Not as placeholders, but as permanent features that must survive production, testing, and service.

That shift changes expectations. Cable quality, termination consistency, and mechanical robustness matter more than they used to.

Power-over-coax quietly raises the bar

Power-over-coax concepts push MMCX even further. Once DC and RF share the same mmcx cable, tolerance for sloppy assemblies drops sharply.

Even if PoC isn’t part of your current design, its presence in adjacent markets influences component quality across the board. Assemblies that used to be “good enough” are now marginal.

For engineers, the takeaway is simple: MMCX is increasingly part of system architecture, not just convenience wiring.

What this means for compact gateways and modules

In small gateways, GPS units, and dense RF modules, reuse is everything.

The same board often feeds multiple products with different antennas, enclosures, or compliance paths.

A disciplined mmcx cable strategy—controlled length, clear transitions, standardized specs—makes that reuse possible without constant revalidation.

How do you standardize mmcx cable specs, testing, and documentation?

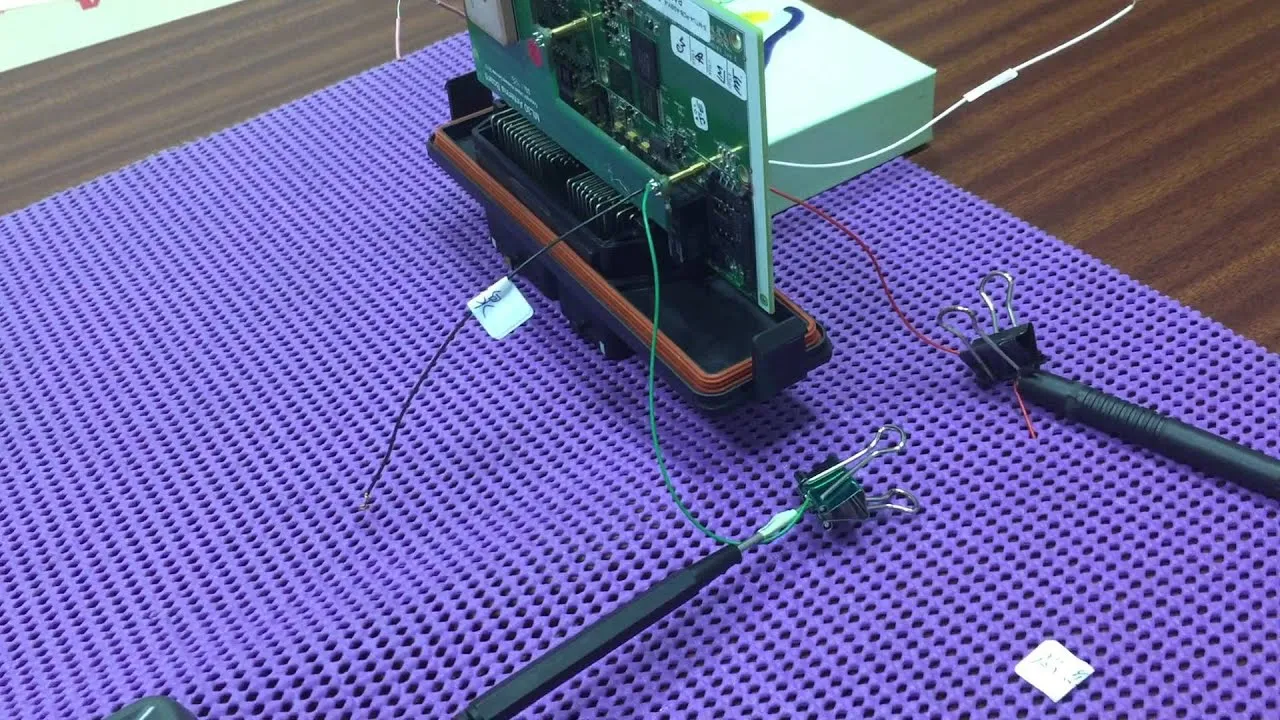

This image depicts a quality control or validation practice. It likely shows an MMCX cable assembly connected to test equipment, such as a VNA, to measure parameters like VSWR or insertion loss. The guide uses this to illustrate the importance of proportional testing (e.g., sampling) to catch assembly drift and ensure consistency, moving beyond just visual inspection.

Stop under-specifying MMCX cables in the BOM

“MMCX cable, 200 mm” is not a specification. It’s a guess.

A usable BOM entry usually spells out:

- Cable family and dielectric

- Length and tolerance

- Board-end MMCX type (plug or jack, straight or right-angle)

- Remote interface (SMA, BNC, antenna)

- Frequency range

- Intended environment

When these details are missing, suppliers fill the gaps themselves. That’s how variability creeps in.

Keep testing proportional to risk

Not every project needs full RF characterization of every cable batch. But doing nothing is rarely wise.

Visual inspection and continuity checks catch gross issues.

Sampling VSWR or insertion loss catches assembly drift before it becomes systemic.

The point isn’t perfection. It’s trend detection.

Turn past mistakes into a checklist

Every team accumulates MMCX scars: bends that were too tight, cables that were just long enough to cause trouble, routing that passed too close to noise.

Writing those down matters.

When those lessons feed back into a simple checklist—and into tools like the MMCX Cable Transition Decision Matrix—future designs start cleaner. Fewer late surprises. Fewer “why did this change?” moments.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I swap a u.FL lead for an MMCX cable without touching the RF design?

Usually no. Impedance may match, but layout, clearance, and mechanical stress change enough to justify rechecking.

How long is “too long” for an MMCX cable at 5 GHz?

There’s no single number, but once you approach a meter, it’s time to question the approach.

Is a single mmcx to SMA cable always better than adapters?

Electrically, often yes. Practically, not always—especially during development.

What causes MMCX failures most often in the field?

Not the connector itself. Routing stress, bending near the termination, and uncontrolled strain are far more common.

When does an external antenna via MMCX make more sense than an on-board antenna?

When tuning flexibility, certification reuse, or future expansion outweighs PCB simplicity.

Closing perspective

The mmcx cable rarely fails loudly.

It doesn’t burn. It doesn’t disconnect. It just shaves margin—slowly, quietly—and makes systems harder to reason about than they should be.

That’s what makes MMCX problems expensive. They don’t look like connector problems at first. They look like antenna drift, unstable measurements, or “one-off” behavior that disappears when the setup changes.

Treat the mmcx cable as a real RF component, with real electrical and mechanical constraints, and it behaves predictably. Ignore it, and it becomes the detail no one remembers specifying—right up until it’s the only thing left to blame.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.