FPC Antenna Guide: 2.4 GHz Layout & Tuning for IoT

Dec 09,2025

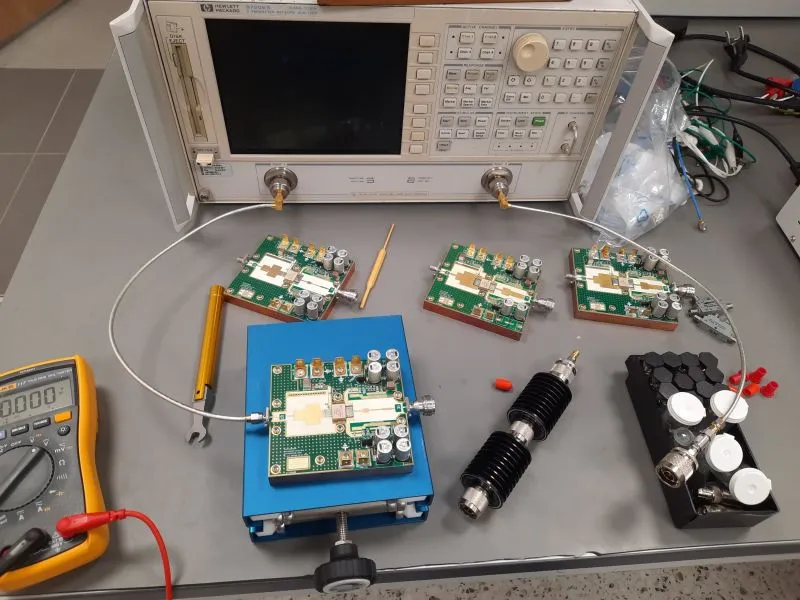

This figure aims to establish a first impression of the complexity of FPC antenna design, visualizing the core argument that “performance is silently decided by layout.” It likely uses a simple comparison (e.g., signal strength bars or radiation diagrams) to show how a well-placed antenna can lead to significant RSSI gains, thereby introducing subsequent detailed discussions on enclosure matching, keep-out planning, and feed routing.

When you’re designing a compact Wi-Fi or IoT board, the performance of an FPC antenna quietly decides whether your signal remains solid or fades after a few meters. Layout isn’t just about sticking a flexible patch—it’s about geometry, grounding, adhesive strength, and cable routing.

A well-placed antenna can deliver 3 to 5 dB stronger RSSI than the same unit mounted behind a battery. Once detuned, no amount of tuning-network magic will rescue it. This guide walks through the real-world process — enclosure matching, keep-out planning, feed routing, and ordering — to help engineers achieve stable 2.4 GHz performance that survives production variance.

Which FPC antenna style fits your enclosure and plastics?

Match geometry to ABS / PC windows

Map the free-space zone early.

- Narrow lids favor linear or meander-line types that follow the wall contour.

- Larger IoT cases benefit from folded or dual-branch antennas for smoother gain.

- Maintain at least 0.5 mm air gap or foam adhesive between copper and plastic to limit detuning.

Some engineers “float” the flexible copper on thin foam. It isolates the trace from uneven wall thickness and cleans up the S11 curve without changing tooling.

Tip: Route the feed trace toward the cable exit rather than a corner—tiny details like that prevent cracked copper after repeated assembly.

Decide adhesive pad area, peel strength, and cable exit angle

Your adhesive layer quietly defines long-term stability. Too soft and it creeps under heat; too stiff and it warps the trace.

For wearables or small IoT nodes:

- Use pad areas ≈ 20 × 40 mm to 25 × 50 mm.

- Select high-temperature acrylic foam tape (peel strength > 12 N/cm).

- Keep the exit angle ≤ 30° relative to the board plane to protect the tiny U.FL to SMA pigtail.

Test at least two adhesive spots — on the upper lid vs the sidewall. Often the higher mount yields 1–2 dB more RSSI simply from better air clearance.

Inside many Wi-Fi devices, angled cable exits ease assembly and relieve strain on the micro-coax tail — a small fix that prevents fatigue failures later.

How do you set ground clearance and RF keep-out for 2.4 GHz?

Ground-clear vs ground-cut: how wide and how far from edges?

Start with proven working values:

- 3 – 5 mm ground clearance (no copper pour) under and around the antenna trace.

- 10 – 15 mm RF keep-out beyond the edges.

- Avoid vias or stitching holes near corners — they attract stray currents.

Validate with a VNA after final assembly; aim for S11 ≤ –10 dB from 2.38 to 2.5 GHz.

If a metal backplate is unavoidable, isolate the antenna zone with narrow ground slots. That tiny change often restores bandwidth without new tooling.

Good clearance discipline separates stable IoT devices from those that drop packets once a day.

Battery, display, and shield cans: metal proximity rules of thumb

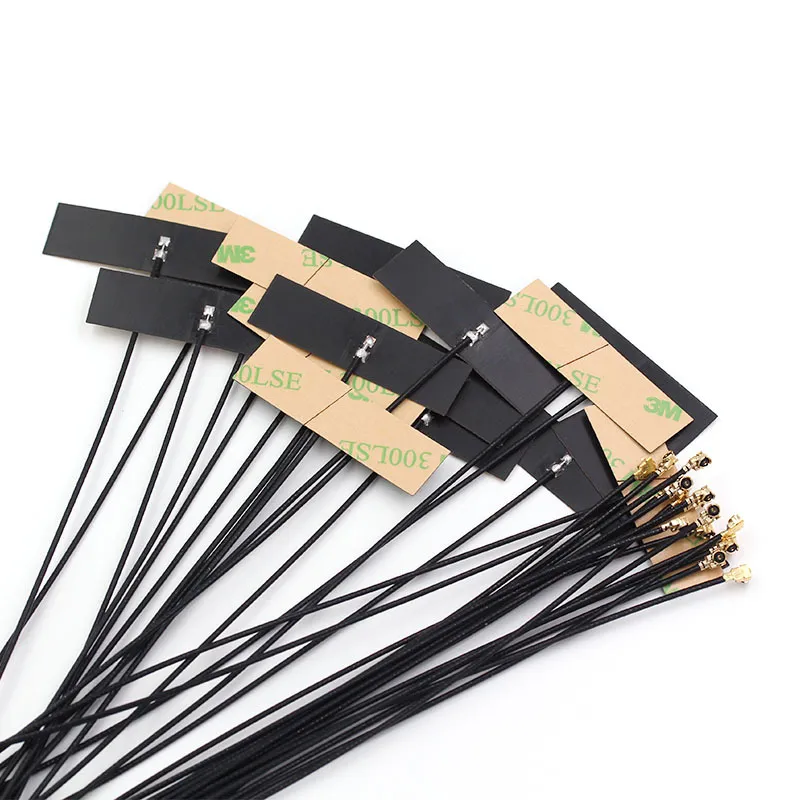

This product image is not an abstract diagram but a specific photo of an actual FPC antenna. Positioned in the section discussing spacing from metal components, its core function is to serve as a physical reference for the textual “rules of thumb.” By annotating or indicating the distances to key components like batteries and metal shields on the photo of a real product, it directly connects the millimeter-level layout constraints that engineers must adhere to for performance, with a tangible, orderable product, making the design specifications more intuitive and actionable.

Nearby metal isn’t inherently bad—it’s about spacing and orientation.

- < 3 mm distance to expect ≈ 5 dB detuning.

- 5 – 10 mm to 1 – 2 dB loss.

- ≥ 15 mm to usually safe with uniform plastic walls.

Parallel surfaces reflect more energy than tilted ones. Rotating the antenna 10–15° often scatters standing waves and flattens impedance.

Check shield-can edges around high-speed ICs; they can re-radiate noise into the antenna region. Temporary copper tape tests often expose coupling paths before you commit to mold changes.

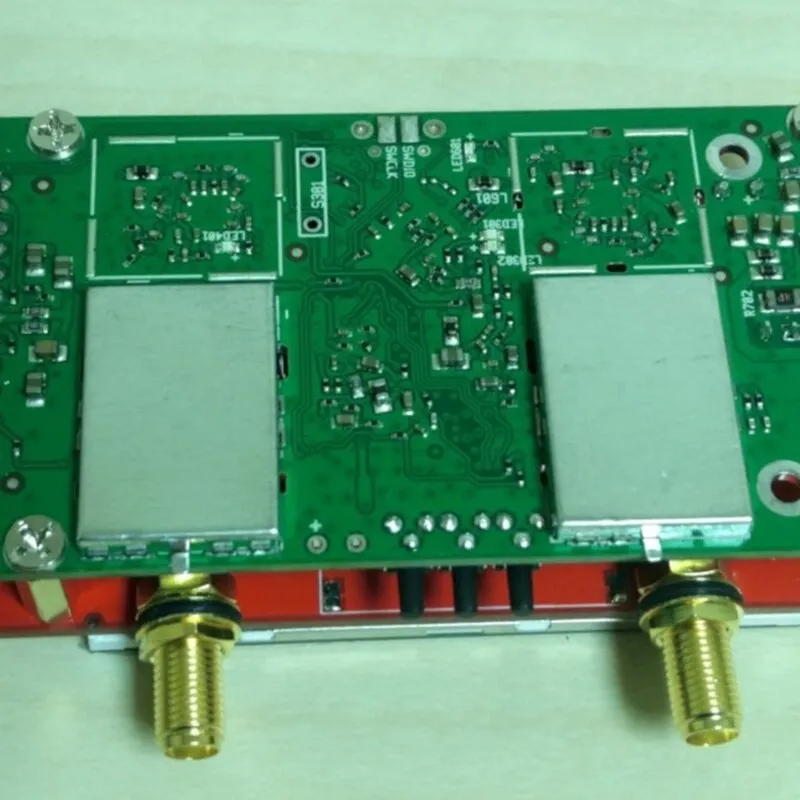

What feed routing and connector choice minimize detuning?

U.FL / IPEX tail routing: bend radius, strain relief and clamp points

Handle those micro-coax tails with care. Maintain bend radius ≥ 5 mm and use strain-relief clamps to avoid connector lift-off under vibration. Stay away from clock lines and switching regulators that inject noise.

For multi-radio boards (Wi-Fi + BT + Thread), label each connector clearly to avoid cross-plugging—a surprisingly common production error.

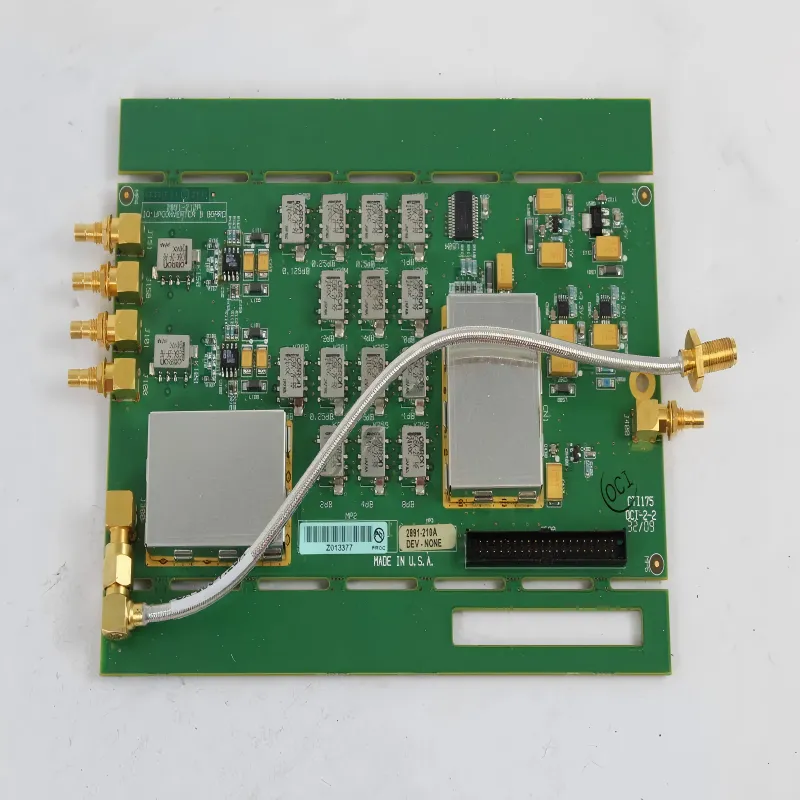

Prototype teams often compare direct U.FL links against SMA bulkhead jumps to measure real loss before finalizing their internal Wi-Fi antenna.

SMA / RP-SMA at panel vs short pigtail jumpers inside the case

This diagram serves the critical trade-off decision between “serviceability” and “RF performance” during the hardware architecture design phase. It visually illustrates the cost of convenience offered by externally accessible connectors—the introduction of extra connector pairs (~0.15 dB loss per pair)—and contrasts it with the simplicity of direct internal connections. This aids engineers in making informed choices based on whether the product is a sealed consumer device or an engineering sample.

This diagram deepens the conceptual choices from Figure 3 into actionable engineering guidance. It not only reiterates the selection logic based on serviceability (engineering samples) versus performance optimization (sealed mass-produced devices) and the quantified loss (~0.15 dB per connector pair) but, more importantly, supplements key mechanical design specifications such as tightening torque and cable strain relief. This ensures that design decisions extend from electrical performance to long-term reliability, serving as the final visual checkpoint for completing the RF link design.

Choose based on serviceability:

- For sealed consumer units, keep connections internal and minimize pairs.

- For engineering samples, bring an SMA feedthrough to the panel for easy debug.

Each connector pair adds ≈ 0.15 dB loss at 2.4 GHz. Two extra pairs already burn 0.3 dB — roughly 7 % of your antenna gain.

Tighten bulkheads around 0.45 N·m to ensure stable contact. If the cable exits downward, fix it with a nylon clip before the bend to prevent mechanical stress and maintain signal integrity over time.

Will cable type and length erode your 2.4 GHz link budget?

0.81 mm vs 1.13 mm micro-coax loss

Both are common in FPC antenna assemblies.

- 0.81 mm micro-coax: ultra-thin, flexible, and easy to route, but roughly 0.008 dB/cm loss at 2.4 GHz.

- 1.13 mm micro-coax: slightly stiffer but about 0.006 dB/cm loss—about 25 % less.

For very short runs (< 10 cm), the thinner type is fine; for anything longer, that 0.002 dB/cm difference quickly adds up. Over 30 cm, you lose almost 1 dB more with 0.81 mm, which can translate to 12 – 15 % less range.

You can visualize it as: each 10 cm of extra coax = roughly 0.07 – 0.1 dB loss. It’s small per centimeter, but unforgiving for battery-powered IoT nodes with tight link budgets.

Connector-pair penalties and cable length limits

Every connector pair—U.FL, IPEX, SMA—costs ≈ 0.15 dB. A chain with two adapters and 25 cm of micro-coax can burn over 1 dB before the signal ever hits free space.

A quick field rule:

- Keep total pigtail length < 20 cm for IoT modules under 20 dBm Tx power.

- For APs or routers with higher Tx levels (> 20 dBm), stay under 30 cm unless using 1.13 mm coax.

- Reduce connector pairs where possible—each one undoes your last calibration effort.

Good design teams include these values in their early layout checklist rather than fixing range issues after the enclosure is molded.

How do you tune the matching network fast (Pi / L) without over-fitting?

S11 targets and coarse/fine steps

Begin with a simple series-L / shunt-C (Pi) network. Tune coarse first using standard values (1.0 nH – 6.8 nH, 0.5 pF – 2.2 pF). Watch how the curve moves:

- If the S11 dip is left of 2.4 GHz, reduce inductance or increase capacitance.

- If it shifts right, do the opposite.

Fine-tune after the antenna is mounted in its real enclosure. Even the adhesive layer adds a fraction of a picofarad of parasitic capacitance.

Try to keep VSWR < 2:1 across 2.38 – 2.5 GHz; for BLE or Thread-only nodes, you can tighten that range around 2.44 GHz for efficiency.

Production tolerance and temperature stability

Your perfect lab match is worthless if it wanders with temperature or plastic batch variance.

To keep production yield high:

- Use stable L/C values with C0G/NPO dielectrics.

- Avoid thin trace gaps that shift after molding stress.

- Test a sample set from both top and bottom antenna locations to cover worst-case environments.

Engineers often accept a slightly wider band (–8 dB S11) in exchange for better cross-unit consistency—a decision that pays off in real-world deployments.

Should you stick with FPC or move to PCB / ceramic for this product?

Trade-offs and coexistence

- FPC antenna: best for plastic housings, low cost, flexible mounting, and moderate gain (1.5 – 3 dBi).

- PCB antenna: integrated and cheap for volume production, but detunes easily with enclosure changes.

- Ceramic antenna: stable and compact, useful for metal frames or tight layouts, though more expensive.

If your device shares space with Bluetooth, Thread, or Matter radios, keep inter-antenna separation ≥ 10 mm and simulate cross-coupling early. That simple step avoids nightmare debug sessions later.

SAR / EMC notes and certification considerations

Internal antennas must still comply with FCC Part 15 and CE EN 300 328 requirements. When testing, mount the antenna exactly as in the final product — adhesive position and cable length included.

A small layout change ( < 5 mm shift ) can invalidate pre-cert results. Document your antenna bill of materials in the product datasheet so the cert lab doesn’t request extra runs.

Always test worst-case channels ( 2402, 2442, 2480 MHz ) under continuous transmit for thermal and SAR validation.

Can you validate placement quickly before freezing the BOM?

A / B adhesive positions and hand detune tests

Build two variants: antenna on lid and antenna on sidewall. Measure RSSI difference in an open field ( 3 – 5 m distance ). If the gap is > 2 dB, the layout change is worth the retool cost.

Also test “hand effects.” Human proximity detunes 2.4 GHz paths by 2–4 dB. Mount the device on a wooden jig and place a hand near the plastic cover to see realistic impact.

OTA smoke tests: throughput vs RSSI vs retry rate

Quick over-the-air (OTA) smoke tests are worth their weight in time saved.

Log three simple metrics: RSSI, throughput, and retry rate.

- RSSI drop > 3 dB vs reference to probable detuning or cable loss.

- Retry rate > 5 % under –60 dBm to impedance mismatch.

- Throughput variance > 10 % to multi-path or polarization error.

Run these tests in a simple office environment before sending to the lab—you’ll catch most major issues for free.

Order like a pro: what must be on your PO and drawing?

A. 2.4 GHz FPC Link-Budget Mini-Calculator

| Input Field | Description / Unit | Example Value |

|---|---|---|

| tx_power_dBm | Transmitter output power | 18 dBm |

| antenna_gain_dBi | Measured antenna gain | 2.5 dBi |

| cable_type | 0.81 or 1.13 mm | 1.13 |

| cable_length_cm | Total length | 20 cm |

| connector_pairs | Count of mated pairs | 2 |

| path_loss_dB | Free-space or empirical loss | 70 dB |

| rx_sensitivity_dBm | Receiver sensitivity | -92 dBm |

Formulas

cable_loss = loss_per_cm(type) × cable_length_cm

conn_loss = connector_pairs × 0.15

EIRP_dBm = tx_power_dBm − cable_loss − conn_loss + antenna_gain_dBi

link_margin_dB = EIRP_dBm − path_loss_dB − rx_sensitivity_dBm

Typical constants (@ 2.4 GHz): loss_per_cm_0.81 ≈ 0.008 dB/cm; loss_per_cm_1.13 ≈ 0.006 dB/cm.

Decision rule: if link_margin < 6 dB, shorten the cable, use lower-loss coax, reduce connector pairs, or optimize matching.

B. FPC Layout & Ordering Matrix

| Antenna Type (FPC) | MOQ | Lead Time | TEJTE SKU | Adhesive Area & Spec | Keep-out Clearance (mm) | Ground Area (mm²) | Cable Type (0.81 / 1.13) & Length (cm) | Connector (U.FL / IPEX to SMA / RP-SMA) | Mount / Exit Angle | Temp Range | Compliance (RoHS / REACH) | Labeling Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FPC-2412 | 500 | 2 weeks | TJT-FPC-2412 | 3M Acrylic Foam (12 N/cm) | 12 | 5 | 1.13 mm / 15 cm | U.FL to SMA | Straight | -40 ~ +85 °C | RoHS 2 / REACH | White label on tail |

| FPC-2430 | 300 | 3 weeks | TJT-FPC-2430 | 3M Acrylic Foam (15 N/cm) | 3 | 10 | 0.81 mm / 25 cm | U.FL to RP-SMA | Angled | -20 ~ +70 °C | RoHS 2 | Laser etched |

What changed in 2024–2025 for internal antennas — and why it matters

If you’re designing wireless gear in 2025, you’ve probably noticed how fast internal antenna standards are evolving. Yet the FPC antenna remains a workhorse — still powering most Wi-Fi and IoT products that need range, not bragging rights.

What actually changed? Three big things:

- Tri-band coexistence. Gateways and routers now squeeze 2.4, 5, and 6 GHz into one enclosure. That means tighter spacing, higher isolation targets, and more emphasis on well-controlled cable routing.

- Accessory standardization. Most major OEMs now align on cable lengths, connector genders, and adhesive specs. Easier for pre-certification, but less freedom for custom shapes.

- Module pre-certification. Many Wi-Fi 6/7 modules arrive with pre-tested internal antennas. You save time, but your layout options shrink — move one part too close, and you lose that certification benefit.

In short, 2.4 GHz isn’t dead; it just learned to coexist politely in crowded devices.

Why 2.4 GHz still rules small IoT designs

You’ll still find 2.4 GHz inside almost every low-power node — smart plugs, thermostats, sensors. The physics are too forgiving to abandon.

- It penetrates walls and plastics far better than 5 GHz or 6 GHz.

- It tolerates tiny ground clearance and flexible form factors.

- It lets designers use cheaper chipsets and lower currents.

When power budget or enclosure size limits your options, 2.4 GHz remains the dependable fallback that “just works.”

FAQ — Practical questions engineers keep asking

How much ground clearance is really enough?

What about keep-out from batteries or screens?

How long can my coax tail be before range drops?

Should I use U.FL only or add an SMA feedthrough?

How do I tune fast without overfitting one unit?

Why does hand placement kill performance?

When to move from FPC to PCB or ceramic?

What should go on the purchase drawing?

Final thoughts

A solid internal Wi-Fi antenna isn’t about luck — it’s about process. Leave breathing room. Keep cables short. Verify before committing to tooling.

Good engineering doesn’t over-design; it repeats what works and measures what doesn’t. Follow these basics, and your 2.4 GHz product will pass certification, ship on schedule, and stay connected long after the glossy demo ends.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.