Flyback Diode Design for Relays, Motors, and SMPS Circuits

Dec 28,2025

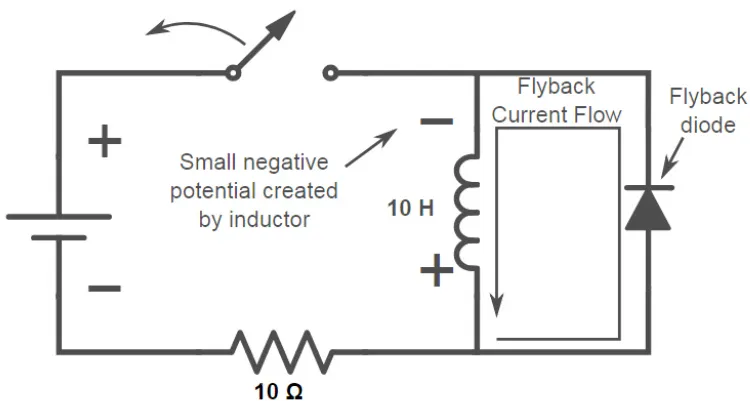

Located at the beginning of the article, this figure visually introduces the basic function and installation position of flyback diodes in different circuits, helping readers establish an initial understanding of circuit layout.

Most power or control boards don’t fail loudly. They age. A relay that used to release cleanly starts sticking. A MOSFET that passed every bench test begins to run warmer each month. An MCU pin degrades without ever seeing an obvious fault.

When engineers dig into these failures, the cause is often mundane rather than exotic: inductive energy that was never given a clean way out.

A flyback diode rarely gets attention during schematic capture. It’s small, cheap, and familiar. Yet in circuits that switch relays, motors, solenoids, or flyback-based SMPS stages, that single component often decides whether stress is absorbed quietly or pushed into devices that were never meant to handle it.

This article doesn’t aim to redefine what a flyback diode is. Instead, it looks at how inductive loads actually behave in real hardware, why some “perfectly valid” diode choices still cause trouble, and how experienced designers think about flyback protection beyond simply adding a diode.

Why do inductive loads absolutely need a flyback diode?

This figure appears in the section “Why do inductive loads absolutely need a flyback diode?” to illustrate the physical process during inductive turn-off and the critical role of the flyback diode.

Anyone who has scoped a relay coil during turn-off knows the result before seeing the waveform.

When current through an inductive load is interrupted, the magnetic field collapses. The current has nowhere to go, and the inductor reacts by forcing the voltage higher until a path appears. This is not a corner case—it’s fundamental electromagnetic behavior and is covered in any basic explanation of inductive kickback, including the overview on Wikipedia.

On paper, the event is short. On hardware, the consequences accumulate.

Repeated overvoltage doesn’t always destroy a switch immediately. More often, it pushes devices into avalanche, erodes safe operating margins, and shortens life in ways that don’t show up during initial validation. That’s why boards can pass testing and still fail early in the field.

A flyback diode changes the outcome by controlling where the energy goes. When the switch opens, the diode becomes forward-biased and allows the current to circulate locally through the coil. The energy stored in the magnetic field is dissipated as heat in the winding resistance and the diode, rather than being converted into a high-voltage spike.

There’s nothing clever about this solution, and that’s the point. It replaces an uncontrolled transient with a predictable decay.

One misconception is worth clearing up early. Engineers often talk about rectifier diodes and flyback diodes as if they belong to different categories. They don’t. What changes is the stress profile.

In flyback service, the diode must repeatedly handle:

- Surge current close to the coil current

- Reverse voltage higher than the supply rail

- Thermal cycling tied to every switching event

A diode that works flawlessly in a low-frequency rectifier can still be a poor choice across an inductive load. The failure mode isn’t immediate—it’s gradual.

Orientation matters as much as selection. A flyback diode must remain reverse-biased during normal operation and conduct only at switch-off. When installed backwards, it doesn’t “half work.” It simply prevents the load from energizing, a mistake still common on relay interface boards and quick-turn prototypes.

How can you quickly map flyback diode use cases for relays, motors, and solenoids?

Experienced designers rarely start flyback protection by asking, “Which diode part number should I use?”

They start by asking, “What kind of inductive behavior am I dealing with?”

That distinction matters more than the diode itself.

Relay coils (5 V, 12 V, 24 V)

Relay coils are usually forgiving. Currents are modest, switching is infrequent, and release time is rarely critical. In most control logic or power sequencing applications, the system doesn’t care whether the relay drops out in 3 ms or 6 ms.

In this context, robustness dominates. A conventional rectifier diode with generous reverse-voltage margin often does exactly what’s needed. The slow current decay keeps voltage stress low and rarely causes side effects.

This is why many industrial control boards continue to use conservative diode choices even when faster devices are available. There’s little to gain by optimizing what isn’t limiting system performance.

Small DC motors (fans, pumps, robotics)

Motors behave differently. They store energy inductively, but they also generate back EMF while spinning. In PWM-driven systems, the switch doesn’t turn off once—it turns off thousands of times per second.

Here, diode behavior starts to matter. A slow diode that was invisible in a relay circuit can become a measurable heat source in a motor driver. Reverse recovery losses and forward voltage drop show up quickly when duty cycles rise.

This is where fast recovery diode or Schottky rectifier diode options usually enter the conversation—not because they are “better,” but because they reduce losses that now matter.

Solenoids and actuators

Solenoids sit somewhere in between. Currents are often higher, mechanical loads are heavier, and timing can matter. In valves or locks, a slow current decay translates directly into slower mechanical release.

Designers sometimes accept higher clamp voltages to speed up energy dissipation. That choice increases electrical stress but improves mechanical response. It’s a trade-off made consciously, not a mistake.

Flyback and SMPS-related windings

In SMPS designs, inductive energy transfer is the operating principle. Diodes are used not only for suppression but for rectification and clamping across transformer windings.

At these frequencies, losses and recovery behavior dominate. Fast recovery diode and Schottky diode rectifier devices are common, while standard rectifiers are usually confined to low-frequency auxiliary paths.

Thinking in terms of relay, motor, solenoid, and SMPS use cases helps narrow the correct diode family long before datasheets or part numbers come into play.

How should you choose a flyback diode from rectifier, fast recovery, and Schottky options?

Once the application context is clear, choosing a flyback diode stops being a part-number exercise and starts looking like stress management.

In real designs, failures rarely come from picking the “wrong category” of diode. They come from underestimating which stress dominates the circuit: voltage margin, current repetition, or heat.

Experienced engineers usually evaluate these factors in a loose order, adjusting priorities based on how the inductive load is actually used.

Reverse voltage: margin beats precision

In flyback operation, the diode almost never sees only the nominal supply voltage. Parasitics in wiring, PCB traces, and the switching device itself add overshoot.

That’s why reverse-voltage ratings are rarely chosen tightly. For low-frequency relay or solenoid loads, many engineers aim for a reverse-voltage rating two to three times higher than the supply. In harsher environments—automotive rails, long cables, or shared power domains—the margin often increases further.

What matters here isn’t hitting an exact number. It’s avoiding repetitive avalanche behavior. A diode can survive occasional overvoltage events, but living there shortens its life quickly.

Forward current and repetitive stress

At the instant the switch opens, the flyback diode conducts roughly the same current that was flowing through the coil. That current then decays over time.

This is why average current ratings alone can be misleading. A diode may look fine on paper yet fail early if it repeatedly handles high peak current without enough thermal recovery time.

Relay coils switching once per second place very different stress on a diode than a motor driver switching thousands of times per second. The current magnitude may be similar, but repetition changes everything.

Forward voltage and heat

Forward voltage determines how quickly magnetic energy is turned into heat inside the diode. In low-duty relay circuits, that heat is usually negligible.

In PWM-controlled motors or solenoids, it becomes significant. This is where schottky rectifier diode devices are often attractive. Their lower forward drop reduces conduction loss and keeps junction temperature under control.

The trade-off is familiar: lower forward voltage usually comes with lower reverse-voltage capability. That limitation must be checked carefully, especially when the supply rail is noisy.

Reverse recovery: when speed starts to matter

Reverse recovery behavior barely matters in a relay that switches a few times per hour. It matters a great deal in SMPS designs and PWM motor drives.

A slow diode stores charge during conduction. When the switch turns on again, that charge must be removed, creating additional current spikes and EMI. Fast recovery diode parts reduce this effect without the voltage limitations typical of Schottky devices.

In practice, the pattern looks like this:

- Standard rectifier diodes fit low-frequency, higher-voltage flyback paths

- Fast recovery diodes fit higher-frequency, higher-voltage environments

- Schottky diode rectifiers fit lower-voltage, efficiency-sensitive designs

This same logic appears repeatedly in power-protection discussions across the TEJTE blog, especially where relay outputs, motor drivers, and SMPS rails coexist on the same board.

Flyback Diode Selection & Stress Estimator

Most engineers don’t calculate flyback stress to the last decimal. They sanity-check it.

The following worksheet-style table reflects how flyback diode choices are often reviewed during schematic checks.

Circuit inputs

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Supply voltage | Nominal coil supply |

| Coil current | Steady-state current before turn-off |

| Coil inductance | Estimated if not specified |

| Ambient temperature | Board-level environment |

| Switching frequency | Relevant for PWM or SMPS |

Candidate diode data

| Field | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Device family | rectifier diode, fast recovery diode, or Schottky rectifier diode |

| Reverse voltage rating | Datasheet maximum |

| Average forward current | Continuous capability |

| Surge current rating | Short-duration current handling |

| Forward voltage | At expected coil current |

| Recovery behavior | Slow or fast |

| Package | Used to judge thermal margin |

Practical stress checks

| Check | Guideline |

|---|---|

| Reverse voltage margin | Rated at least two to three times supply |

| Forward current | Must exceed coil current |

| Energy handling | Coil energy well below diode limits |

| Heat dissipation | Temperature rise feels reasonable on paper |

Decision flags

- Red flag: reverse-voltage rating below safe margin

- Red flag: forward current below coil current

- Yellow flag: small package in high-frequency switching

- Yellow flag: noticeable heating in PWM operation

Borderline cases are usually solved by stepping up package size or switching diode families, not by trimming margins.

This kind of estimator doesn’t replace datasheets. It replaces surprises during field deployment.

How this ties into a real board-level design

Flyback protection rarely exists in isolation. It interacts with reverse-polarity protection, transient suppression, and SMPS clamp networks.

That’s why many engineers review flyback diodes alongside other protection elements already discussed across TEJTE’s power and protection articles, especially when multiple inductive loads share a common supply rail.

When should you treat the flyback path as a clamping diode or RC snubber network?

If all you ever switch are low-speed relays, a basic flyback diode usually does the job quietly. That’s why it became the default in the first place.

The problem shows up when timing starts to matter.

With a simple flyback diode across a coil, the voltage during turn-off is held close to ground. That keeps the switch safe, but it also means current decays slowly. The magnetic field collapses gently, and the mechanical part follows at its own pace.

If you’ve worked with solenoid valves, locks, or fast actuators, you’ve probably seen this firsthand. The electrical side looks fine, but the mechanism feels sluggish. At that point, the question isn’t whether the flyback diode works—it’s whether it works fast enough.

This is where designers allow the voltage to rise intentionally. A clamping diode arrangement limits the peak voltage to a defined level rather than forcing it near zero. Letting the voltage climb speeds up current decay and shortens release time. The trade-off is obvious: higher electrical stress in exchange for faster mechanical response.

The underlying physics isn’t controversial; it’s the same inductive energy release described in most discussions of flyback behavior, including the general overview on Wikipedia. What changes from design to design is how much stress you’re willing to tolerate to gain speed.

RC and RCD snubber networks enter the picture for similar reasons, especially in power supplies. Instead of hard clamping, they absorb and shape energy. In practice, these networks are rarely “perfectly calculated” up front. Most are adjusted during bring-up until waveforms look reasonable and parts stop running hot—something that comes up repeatedly in SMPS-related design notes across the TEJTE blog when discussing flyback-based converters and auxiliary windings.

The important part isn’t which method you choose. It’s choosing deliberately, rather than inheriting a default.

How do you integrate flyback diodes into SMPS and PWM control without killing efficiency?

Flyback protection feels invisible until switching frequency goes up.

In a relay circuit that switches occasionally, diode losses barely register. In PWM motor drives and SMPS stages, they show up quickly—often as heat that doesn’t quite make sense at first.

Every off-transition forces current through the flyback path. If the diode has a high forward drop or slow recovery, you pay that penalty every cycle. Multiply it by thousands of cycles per second and the loss becomes real.

This is why fast recovery diode and schottky rectifier diode devices appear so often in high-frequency designs. Not because they’re fashionable, but because they waste less energy per transition. The same trade-off shows up repeatedly in SMPS discussions on tejte.com, where rectification, clamping, and freewheeling all interact with overall efficiency.

One pattern many engineers recognize: a power stage that runs cool at light load but warms up faster than expected as duty cycle increases. Switch and magnetics look fine. Eventually, attention turns to the diode path.

In flyback converters, the effect is even more pronounced. Diodes don’t just protect—they shape waveforms. Recovery behavior affects switching edges and EMI, which is why diode choice often gets revisited late in the design, after real hardware exposes what simulations missed.

If efficiency or thermal margin matters, the flyback path deserves the same scrutiny as the main switch. Treating it as a background detail is how losses slip through reviews.

How should you place, route, and test flyback diodes on a PCB to minimize EMI issues?

A correct schematic doesn’t guarantee a quiet board.

The loop formed by the inductive load, the switch, and the flyback diode carries fast-changing current. If that loop is large, it radiates. If it’s tight, it behaves.

This is why experienced designers think about placement before part numbers. A modest diode placed well often outperforms a “better” diode placed poorly.

In practice, that means keeping the flyback loop short and direct. Long detours, shared return paths, and unnecessary vias all add inductance. On dense boards, the diode usually ends up closer to the switch than the load—not because it’s ideal, but because it minimizes loop area.

Polarity marking matters more than people admit. On small SMD parts, unclear orientation leads to reversed diodes. That mistake doesn’t always cause immediate failure; it just makes the circuit behave strangely, which is harder to debug.

Testing should go beyond “it works.” Probing the switching node during turn-off shows immediately whether the flyback path is effective. Comparing waveforms between a simple diode, a clamp, and a snubber often reveals trade-offs that aren’t obvious on paper. Layout-related EMI issues discussed in several TEJTE PCB-level articles tend to surface this way—on the scope, not in the schematic.

What flyback diode design trends are emerging in automotive and industrial markets?

This figure is located in the section discussing market trends, visually presenting the trend of flyback diodes evolving towards higher reliability and more specialized design in demanding application environments.

Flyback protection used to be informal. A diode was added because it always had been.

That approach doesn’t hold up well in modern systems.

Higher voltages, higher ambient temperatures, and longer service life leave less margin for uncontrolled stress. In automotive and industrial designs, flyback paths are now reviewed explicitly, alongside reverse-polarity protection and transient suppression—an approach reflected in newer protection-focused content across the TEJTE blog.

Another shift is specialization. High-power paths use robust devices with generous margins. Low-power sensing and auxiliary circuits often use small, fast diodes for localized protection rather than board-wide brute force. The idea that one diode choice fits the entire design is fading.

This figure further elaborates on the trend introduced in Figure 3, showing through comparison how tailored flyback protection solutions are adopted for different circuit sections (main power vs. auxiliary sensing) in modern designs.

FAQ

How do I size a flyback diode for a 12 V relay coil?

Start with the coil current. Choose a diode that comfortably carries that current and has plenty of reverse-voltage margin. Conservative choices usually age better.

When does a Schottky rectifier diode make sense for flyback protection?

When switching frequency is high or losses start to matter. PWM motor drives and SMPS stages are typical cases.

Is a fast recovery diode better than a standard rectifier for flyback?

Often yes, especially when voltage is high and switching is frequent. Reduced recovery loss helps both efficiency and EMI.

What’s the practical difference between a flyback diode and a clamping diode?

A flyback diode keeps voltage low but releases energy slowly. A clamp allows higher voltage so energy dissipates faster.

Where should the flyback diode go on the PCB?

As close as possible to the switch or load, with the smallest practical loop. Placement often matters more than diode type.

Can small signal diodes be used for flyback protection?

Only for very low-energy loads. Surge current and heating usually set the limit.

Final thought

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.