BNC Cable Selection Guide for Video, CCTV, and RF Test

Jan 10,2025

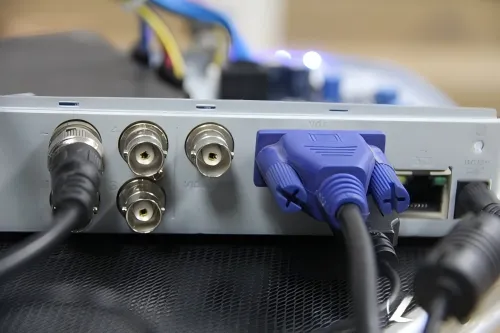

This introductory graphic establishes the central theme: BNC cables, often an afterthought in CCTV, broadcast, and RF systems, can silently erode performance margins. It visually represents the cable as the potential weak link that connects critical equipment.

In most systems, the bnc cable is never the first thing specified. Engineers focus on the camera model, the recorder, the test instrument, or the RF module. The cable is added later, often pulled from whatever inventory already exists. On paper, that makes sense. In practice, it’s where margins quietly disappear.

Across CCTV installations, broadcast video chains, and RF test benches, the BNC link is usually short, passive, and assumed to be harmless. Yet this “last few meters” frequently decides whether a signal stays clean, a video link holds at distance, or a measurement can be trusted. When problems appear, the cable is rarely blamed first. By then, it’s already embedded in the system.

This guide looks at how bnc cable, bnc coaxial cable, 50 ohm bnc cable, 75 ohm bnc cable, bnc camera cable, and bnc video cable actually behave once they leave datasheets and enter real deployments. The goal is not to catalog parts, but to reduce the kind of quiet, expensive mistakes that show up months after installation.

Where does a BNC cable actually sit in modern signal paths?

This diagram visually maps the ubiquitous role of the BNC interface, connecting vastly different equipment like CCTV cameras, SDI broadcast gear, and RF test instruments (oscilloscopes, signal generators). It highlights the common expectation for the cable to be a transparent, non-limiting component.

The BNC connector survives because it spans very different worlds. Surveillance cameras, broadcast equipment, oscilloscopes, RF generators, timing modules—all rely on it. What ties these systems together is not the connector itself, but the expectation that whatever sits between two ports will not become the limiting factor.

In CCTV systems, a bnc camera cable typically carries baseband or digitally modulated video from camera to DVR or encoder. The signal is sensitive to attenuation, reflections, and shielding quality, even when resolution appears modest. In broadcast environments, bnc video cable assemblies link cameras, switchers, and recorders using SDI standards where timing margins are far tighter and tolerance for mismatch is minimal.

On the lab bench, the same bnc cable form factor connects signal generators, oscilloscopes, counters, and spectrum analyzers. Here the cable may carry RF, fast trigger edges, or reference clocks. A link that is “good enough” for video can distort measurements or introduce reflections that undermine confidence in test results. Different use cases, same interface, very different consequences when the cable choice is wrong.

Distinguishing bnc coaxial cable from bulk coax and rack wiring

This image contrasts a ready-to-use BNC jumper cable with raw bulk coaxial cable. It underscores the key point: factory-terminated BNC cables offer controlled impedance and consistent performance, whereas bulk cable’s performance depends heavily on field termination quality, making it a variable in system reliability.

A finished bnc coaxial cable is often treated as interchangeable with bulk coaxial cable plus connectors. Electrically, they may share the same family name—RG59, RG6, RG58—but their roles are not the same. Factory-assembled BNC cables are built to controlled impedance with consistent connector geometry and termination quality. That repeatability is why short BNC jumpers behave predictably across systems.

Bulk coax, by contrast, is designed for permanent runs. It is pulled through ceilings, conduits, and risers, then terminated onsite. That flexibility comes at a cost. Termination quality, connector selection, and installer technique suddenly become variables. In many troubleshooting cases, the visible bnc cable jumper gets blamed, while the real issue sits hidden inside a wall.

Rack wiring and patch panels add another layer. They organize signals and simplify maintenance, but they do not compensate for poor trunk cable selection. Treating rack jumpers and building runs as interchangeable is one of the most common structural mistakes in mixed video and RF systems.

Using short bnc coaxial cable segments to protect long trunk runs

A stable architecture separates responsibilities. Long-distance paths are handled by RG59 or RG6 trunk cables chosen for attenuation and environment. Short bnc coaxial cable segments—typically half a meter to two meters—are used inside racks, camera housings, or test setups to provide flexibility and service access.

This approach limits mechanical stress, simplifies replacement, and keeps electrical performance predictable. Problems arise when these roles are reversed, such as using thin jumpers for long runs or forcing stiff trunk cable into tight equipment spaces. Those choices rarely fail immediately, but they age poorly.

Engineers who need to cross-check attenuation behavior and frequency limits of RG families commonly used behind BNC connectors often refer back to a broader RG overview during design reviews. That context is covered in more detail in our general RG cable guide, which helps frame where BNC-terminated cables fit within the wider coax ecosystem.

How do you choose between 50 ohm BNC cable and 75 ohm BNC cable without guessing?

Impedance mismatch is the most common root cause behind subtle BNC-related failures. The connectors mate cleanly, the system powers up, and initial results look acceptable. Over time—or under stress—the margins vanish.

Most RF and measurement equipment is designed around 50 Ω. Signal generators, RF switches, spectrum analyzers, and many oscilloscopes assume that impedance from output to load. Using a 50 ohm bnc cable keeps reflections low and preserves amplitude accuracy. Substituting a 75 Ω cable into that path introduces mismatch that becomes increasingly visible as frequency rises, even if the system appears functional at first glance.

Video systems live in a different impedance world. Analog CCTV, digital surveillance formats, and SDI-based broadcast chains are all specified around 75 Ω. A 75 ohm bnc cable ensures that source, cable, and load behave as a matched system. In SDI links especially, even a single mismatched cable can reduce maximum usable length or introduce intermittent dropouts that are difficult to reproduce.

Although many 50 Ω and 75 Ω BNC connectors will mate mechanically, that compatibility is misleading. Above roughly 10 MHz, impedance mismatch produces measurable reflections and signal degradation. In low-frequency control or legacy audio paths, the effect may be tolerable. In CCTV, SDI, or RF measurement, it rarely is. For teams that want a deeper technical breakdown of mismatch behavior and connector geometry, this topic is explored further in our BNC 50 Ohm vs 75 Ohm comparison guide, which focuses on lab and video use cases.

What length and loss planning keeps your BNC cable video links stable?

Most BNC video problems don’t come from obvious mistakes. They come from systems that technically meet the numbers, but leave no room for reality. A bnc cable that is “within spec” on paper can still be the weakest point once distance, connectors, routing, and aging stack together.

In CCTV and SDI deployments, links rarely fail outright. Instead, they drift. Images lose sharpness. Dropouts appear only at certain times of day. Systems that worked during commissioning become unreliable months later. By the time anyone suspects the cable, it’s already buried in walls or locked into racks.

Estimating attenuation budgets for long CCTV and SDI bnc cable runs

All coaxial cables lose signal as length increases. That sounds obvious, but the way loss shows up is often misunderstood. With common bnc camera cable based on RG59, attenuation is usually invisible at short distances. Push the run longer, and the signal still arrives—but with less margin. Noise creeps in. Edges soften. Compression artifacts become easier to notice.

SDI makes this effect harder to ignore. As video formats moved from SD to HD and then to 3G and 12G, the usable distance of the same cable shrank dramatically. This isn’t marketing pessimism; it’s physics. Higher data rates concentrate energy at higher frequencies, where coaxial loss rises sharply. Broadcast engineers have been dealing with this reality for years, which is why SDI specifications published by organizations like SMPTE are strict about link budgets and return loss.

What matters in practice is not the exact dB-per-meter number, but whether your planned run leaves headroom. If a cable length sits close to the published maximum for a given format, it will work—until connectors age, temperature changes, or routing shifts slightly. That’s when “mystery” problems start.

Treating short rack-to-device bnc cable jumpers differently from building trunk lines

Not every BNC connection deserves the same level of concern. A short bnc cable jumper inside a rack behaves very differently from a long run through a ceiling or conduit. For jumpers under a meter or two, connector quality and shielding matter far more than bulk attenuation.

Trouble appears when these roles get mixed. Using thin, flexible jumpers for long CCTV runs saves effort during installation but leaves the system operating on the edge. On the other side, forcing thick trunk cable into tight racks adds mechanical stress and shortens connector life. Stable systems separate these functions deliberately: trunk cables for distance, short BNC jumpers for flexibility.

Engineers who design mixed video and RF environments often sanity-check this separation by stepping back to basic coax behavior—geometry, dielectric, length—before worrying about connector style. That broader view of coaxial transmission lines, rather than connector branding, tends to surface early in experienced design reviews.

Deciding when to upgrade from basic bnc video cable to lower-loss coax

Most upgrades happen incrementally. A CCTV system starts analog. Then it moves to HD. Later, frame rates increase or SDI equipment gets introduced. Each step raises bandwidth demands and quietly reduces tolerance for loss.

When links approach their practical limit, upgrading from a generic bnc video cable to a lower-loss, broadcast-grade coax often restores margin without redesigning the system. Past that point, however, no amount of cable swapping will help. Inline equalizers, active repeaters, or fiber conversion become unavoidable. The key skill is recognizing when you’ve crossed that boundary—before field failures force the decision.

How should you route, terminate, and protect BNC cables for long-term reliability?

Respecting bend radius and strain relief rules for bnc coaxial cable

Coaxial cable depends on consistent spacing between conductors to maintain impedance. Sharp bends distort that geometry. The cable may still pass continuity checks, but its electrical behavior changes permanently. A common field rule—keeping the bend radius at roughly ten times the cable diameter—exists for a reason, not tradition.

Strain relief is just as important. Without support, repeated flexing near the BNC connector slowly breaks the shield or center conductor. The failure doesn’t happen all at once. It shows up as intermittent noise, sensitivity to movement, or unexplained loss that disappears when the cable is touched.

Choosing straight versus right-angle BNC connectors in tight spaces

Right-angle BNC connectors solve real problems. They reduce stress in dense racks and behind wall-mounted equipment. Electrically, they introduce a small discontinuity. In low-frequency video or control signals, this rarely matters. In higher-bandwidth SDI or RF paths, stacking multiple right-angle transitions can add up.

The practical approach is moderation. Use right-angle connectors where space demands it. Avoid using them as a default everywhere, especially in critical links that already operate close to their margin.

Weatherproofing outdoor bnc camera cable connections

Outdoor failures are almost never caused by impedance mismatch. They are caused by water. Moisture creeps into connectors, degrades shielding, and corrodes contacts long before a cable goes open-circuit.

Effective protection relies on basic field discipline: proper drip loops, self-amalgamating tape, heat-shrink boots, and jackets rated for UV exposure. These practices are common across outdoor telecommunications and video infrastructure. Skipping them doesn’t cause immediate failure, which is why the mistake is so common—and so expensive later.

How are market trends and new standards changing BNC cable requirements?

BNC has been declared “obsolete” many times, yet it remains everywhere cameras and test equipment exist. What has changed is not the connector, but what engineers expect it to carry.

Surveillance systems continue to grow in scale and resolution, pushing bnc camera cable closer to its practical limits. In broadcast environments, 12G-SDI allows 4K video over a single cable, but only if 75 ohm bnc cable assemblies maintain tight impedance control and low loss. The margin for sloppy installation is smaller than it used to be.

These shifts mirror a broader pattern seen across RF and video engineering: legacy interfaces survive by adapting. The bnc cable is no longer just “good enough.” It is expected to behave predictably at higher bandwidths, longer distances, and in harsher environments than before.

How can a simple matrix turn BNC cable specs into an error-free purchase order?

Most BNC-related purchasing errors don’t come from ignorance. They come from ambiguity. Someone writes “BNC cable” on a drawing or PO. Another person interprets it as whatever they used last time. The system works—until a different impedance, bandwidth, or environment quietly breaks compatibility.

The fastest way to eliminate this class of error is to collapse technical decisions into a small number of explicit fields that everyone understands the same way.

Capturing impedance, bandwidth, and environment in one bnc cable spec line

A usable specification line doesn’t try to educate the reader. It states facts. At minimum, it should lock down impedance, intended signal type, approximate bandwidth, length, and environment. Once those are fixed, cable family and connector style usually become obvious.

Teams that work across both video and RF domains often discover that writing impedance explicitly—rather than assuming it—eliminates more mistakes than any other single change. This aligns with how impedance matching is treated in general transmission line theory, where the system, not the connector, defines acceptable behavior.

Standardizing names for bnc camera cable vs RF and SDI bnc video cable

Naming conventions matter more than most teams expect. When SKUs encode impedance and application, installers stop guessing. A label that clearly distinguishes bnc camera cable from SDI-grade bnc video cable prevents misuse even when documentation is ignored.

Examples that work well in practice look boring—and that’s the point. They trade elegance for clarity.

BNC Cable Application & Impedance Selector

This practical selection matrix provides clear, at-a-glance guidance. It correlates key parameters—Application Context (CCTV, SDI, RF Lab), Required Impedance (75Ω or 50Ω), Typical Length, and Environment—with the Recommended Cable Class (e.g., RG59-based, low-loss video cable, RG58). It's a tool to eliminate ambiguity in cable specification.

| Application Context | Signal Characteristics | Typical Length | Environment | Required Impedance | Recommended Cable |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCTV (analog / HD) | Baseband / low-GHz content | 30-80 m | Indoor / Outdoor | 75 Ω | RG59-based BNC camera cable |

| Broadcast SDI | HD / 3G / 12G-SDI | 10-40 m | Studio | 75 Ω | Low-loss BNC video cable |

| RF lab bench | RF ≤ hundreds of MHz | ≤ 2 m | Indoor rack | 50 Ω | RG58 50 Ω BNC cable |

| Scope trigger / sync | Fast edges, low power | ≤ 1 m | Indoor | 50 Ω | Short BNC coaxial cable |

Loss estimation (rule-of-thumb):

Estimated loss ≈ (typical loss per meter for cable family) × (run length)

Risk flags:

- < 3 dB: Comfortable margin

- 3–6 dB: Check system tolerance

- 6 dB: High risk—change cable class or architecture

What makes this matrix useful is not precision, but alignment. It gives engineering, purchasing, and installation the same mental model, reducing interpretation drift. Many teams later formalize this into templates or small internal tools once the logic proves itself.

When do BNC cables need to interface cleanly with SMA, N, and other RF connectors?

This close-up shows a common RF adapter used to interface equipment with SMA connectors (common on modern RF modules) to systems using BNC. The guide cautions against excessive use of such adapters in signal chains, as each one introduces a small electrical discontinuity and a potential mechanical failure point.

This image depicts a purpose-built hybrid jumper cable. The guide recommends using such dedicated jumpers (e.g., SMA-to-BNC) instead of stacking multiple adapters, as they provide a more reliable, electrically superior, and mechanically robust connection between different connector families in mixed systems.

Planning BNC-to-SMA and BNC-to-N jumpers between instruments and DUTs

On benches and in field kits, it’s tempting to chain adapters: BNC-to-BNC, then BNC-to-SMA, then SMA-to-N. Electrically, each adapter introduces a small discontinuity. Mechanically, each joint adds a failure point.

A short, purpose-built jumper—BNC on one end, SMA or N on the other—almost always performs better than stacked adapters. This practice mirrors how RF interconnects are treated in measurement standards, where minimizing transitions is a basic assumption rather than a special case.

Avoiding adapter stacks when a custom bnc cable jumper will do

Adapter stacks tend to become permanent by accident. What starts as a temporary workaround stays in place because “it works.” Months later, intermittent noise or drift appears, and the adapter chain is forgotten.

Replacing that stack with a single bnc cable jumper usually removes multiple variables at once: fewer interfaces, better strain relief, and clearer intent.

Defining a small standard set of cross-family BNC jumpers

Which review questions about BNC cable should your team answer before deployment?

Has every critical link been checked for impedance, bandwidth, and length?

Do engineering, purchasing, and installation teams use the same bnc cable names?

Which recurring bnc cable problems deserve a permanent FAQ?

Practical FAQ

Can 50 Ω and 75 Ω BNC cables be mixed in the same system?

They can be connected mechanically, but electrically it’s rarely a good idea outside low-frequency control signals. For CCTV, SDI, and RF measurement, impedance consistency matters more than convenience.

Why did video quality drop after replacing a cable that “looked identical”?

The most common causes are impedance mismatch, higher attenuation from a thinner cable, or degraded shielding. bnc camera cable is not interchangeable with RF-grade bnc coaxial cable, even if the connectors fit.

Is 75 Ω really mandatory for HD-SDI and 12G-SDI?

Yes. SDI standards assume a continuous 75 Ω path. Deviations reduce margin and increase sensitivity to length, temperature, and connector wear.

How do I know when a run is too long for BNC video?

When a cable length approaches published limits for its format, the system has no buffer left. If problems appear intermittently, you are already past the safe zone.

Does it ever make sense to use 50 Ω BNC for low-frequency sync or control?

At very low frequencies, the difference is minimal. Many teams still standardize on one impedance to reduce confusion and inventory errors.

What is the simplest way to prevent BNC-related installation mistakes?

Write impedance, cable family, length, and environment explicitly in drawings and purchase orders. Ambiguity causes more failures than bad hardware.

Closing note

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.