12V to 5V Buck Converter Design in Practice

Dec 19,2025

Which controller and topology fit a 12V to 5V buck?

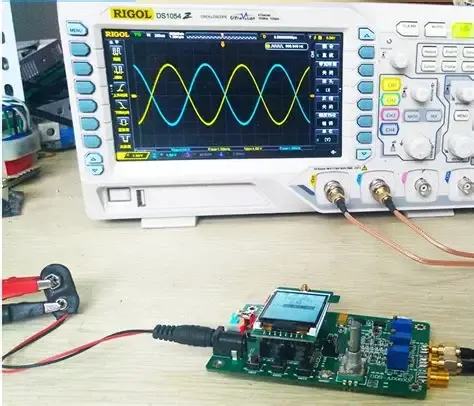

This oscilloscope screenshot serves as the entry point of the document, visually revealing the gap between paper design and physical reality in power supply design. It emphasizes that even a seemingly simple voltage conversion task can face challenges in actual layout, component selection, and noise control. The “cracker icon” in the image may indicate a measurement point or anomaly, echoing the statement that “in real boards it’s rarely that neat.”

Converting 12 V down to 5 V looks simple on paper, but in real boards it’s rarely that neat. You’ve got choices ranging from the classic MC34063 to today’s high-efficiency synchronous switching regulators, each carrying its own quirks. Picking the right one is more about the project’s trade-offs—heat, cost, and part availability—than about what’s newest.

A buck converter slices the input voltage with a switch and smooths it with an inductor and capacitor. For a 12 to 5 V drop, both asynchronous (with a diode) and synchronous (with dual MOSFETs) architectures work. The question is: how much simplicity do you want to keep versus how much efficiency you need to gain?

If you’re targeting under 1 A output and don’t mind a modest footprint, the MC34063 or MC34063A still earns its place. It runs at roughly 50 – 100 kHz, needs just a handful of passives, and shrugs off line noise. Many engineers favor it because it’s predictable, inexpensive, and stocked nearly everywhere. It’s easy to repair in the field—part of why you’ll still find it inside routers and sensor hubs.

Newer MOSFET-based regulators, such as TI’s LM2596 or Microchip’s MCP16331, push efficiency well above 90 %. They’re faster and smaller, but fussier about layout. High-frequency switching leaves little room for sloppy grounding or trace loops, so once you cross the 1 A mark or face thermal limits, migrating to a synchronous design makes sense.

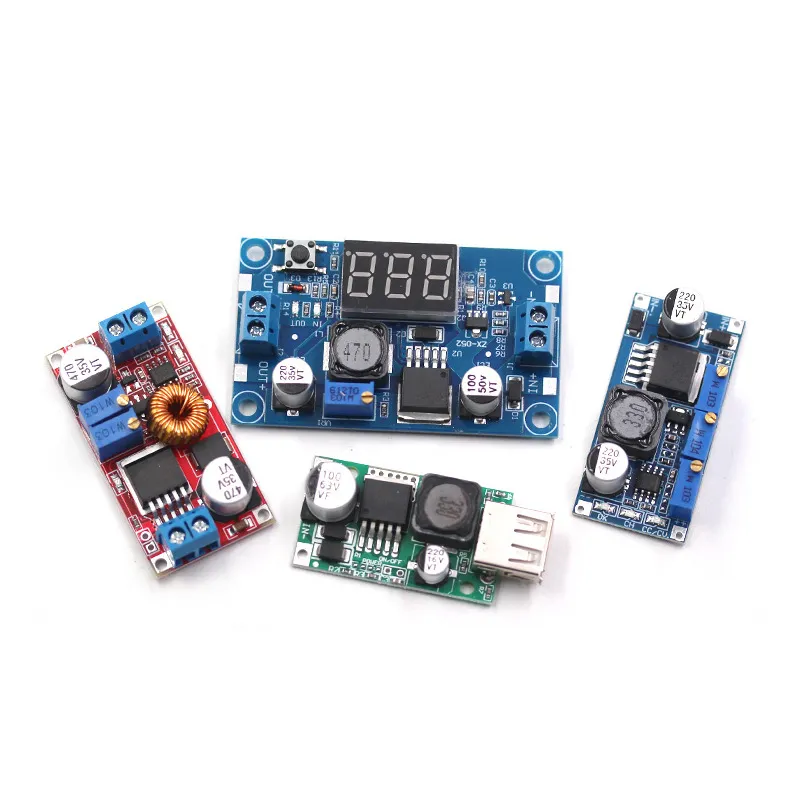

This graphic visualizes the critical decision-making process at the initial design stage. It translates abstract “project trade-offs” into concrete conditional judgments, guiding engineers to select the appropriate controller architecture based on practical questions like whether output current is below 0.8A, ambient temperature is below 60°C, efficiency above 90% is required, or strict EMC compliance is mandatory. This reflects the evolution of design thinking from “functional” to “optimized.”

A quick mental checklist helps:

- Stay with MC34063/34063A if

• Output ≤ 0.8 A

• Ambient < 60 °C

• EMI tolerance is moderate

• Board space isn’t a constraint

- Go synchronous if

• Efficiency > 90 % is critical

• You’re bound by automotive or EMC rules

• You need smaller inductors and capacitors

For many prototypes, engineers start with MC34063 modules to prove functionality, then shift to modern bucks during optimization. The transition point becomes obvious when the old chip’s TO-92 switch runs too warm. A deeper comparison of its limits and math examples is available in the MC34063 calculator & limits guide—handy before committing a final PCB spin.

Compute the core parameters before you place any parts

Duty cycle (D)

[ D \approx \frac{V_{out} + V_F}{V_{in} – V_{sat}} ]

Where (V_F) is the diode drop (≈ 0.4–0.5 V for Schottky) and (V_{sat}) the switch saturation (≈ 0.2 V on MC34063).

At 12 V in and 5 V out, D ≈ (5.4 / 11.8) ≈ 0.46 to the switch is on 46 % of each cycle.

Ripple current (ΔIL)

[ ΔI_L = k·I_{out} ]

Pick k ≈ 0.2 – 0.4. For 0.5 A load, ΔIL ≈ 0.15 A when k = 0.3.

Low ripple means big inductors; high ripple means higher voltage noise. Balance is key.

Inductance (L)

[ L \approx \frac{(V_{in}-V_{out}-V_{sat})·D}{ΔI_L·f_{sw}} ]

Example: 12 V to 5 V, ΔIL = 0.15 A, f_sw = 50 kHz to L ≈ 1.6 mH, unrealistically large.

Boost f_sw or ΔIL to cut L down to ≈ 330–470 µH, which fits MC34063 builds.

Peak current (Ipk)

[ I_{pk} = I_{out} + \frac{ΔI_L}{2} ]

At 0.5 A load, Ipk ≈ 0.575 A. That defines the minimum inductor and diode ratings.

Sense resistor (Rsc)

For MC34063, current-limit ≈ 0.3 V across Rsc:

[ R_{sc} \approx \frac{0.3 V}{I_{pk,limit}} ]

Targeting 0.6 A limit to Rsc ≈ 0.5 Ω.

Use 0.47 Ω (¼ W) and keep traces short to prevent false triggers.

12V to 5V Buck Quick Calculator

| Parameter | Formula | Example (0.5 A) | Example (1 A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Voltage (Vin) | - | 12 V | 12 V |

| Output Voltage (Vout) | - | 5 V | 5 V |

| Diode VF | - | 0.45 V | 0.45 V |

| Switch Vsat | - | 0.2 V | 0.2 V |

| Duty Cycle (D) | (Vout + VF) / (Vin – Vsat) | 0.46 | 0.46 |

| Ripple Ratio (k) | - | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Ripple Current ΔIL | k × Iout | 0.15 A | 0.30 A |

| Inductance (L) | (Vin – Vout – Vsat) · D / (ΔIL · fSW) | 330 μH @ 50 kHz | 150 μH @ 100 kHz |

| Peak Current (Ipk) | Iout + ΔIL / 2 | 0.58 A | 1.15 A |

| RSC (MC34063) | 0.3 V / Ipk | 0.51 Ω | 0.26 Ω |

| Output Ripple (ΔVout) | ΔIL·ESR + Iout·D(1-D)/(Cout·fSW) | ≈ 35 mV @ 100 μF 0.1 Ω | ≈ 60 mV @ same cap |

| Diode Currents (avg / pk) | Iout / Ipk | 0.5 A / 0.58 A | 1 A / 1.15 A |

Output ripple and capacitor behavior

Ripple control boils down to ESR and capacitance:

[ ΔV_{out}=ΔI_L·ESR+\frac{I_{out}·D(1–D)}{C_{out}·f_{sw}} ]

Keeping ripple < 50 mV is a practical goal.

Example: 100 µF electrolytic, 0.1 Ω ESR to ≈ 35 mV p-p at 0.5 A.

Add a 1 µF ceramic in parallel and you’ll halve the high-frequency edge. Simple trick, big payoff.

Thermal headroom and real-world efficiency

At 12 to 5 V and 0.5 A, the circuit pushes 2.5 W out while burning ~3.5 W in; ≈ 1 W of that turns into heat. A 0.4 Ω inductor can hit 70 °C after minutes of steady draw. Choose low-DCR cores and short, thick traces. Those few degrees matter when you’re chasing MTBF targets. For noise control near sensitive signals, check TEJTE’s note on TVS/ESD placement near DC-DC to see how return currents interact with your buck’s ground path.

In short, math gets you close; thermals and layout finish the job.

How do you select the inductor and the Schottky diode?

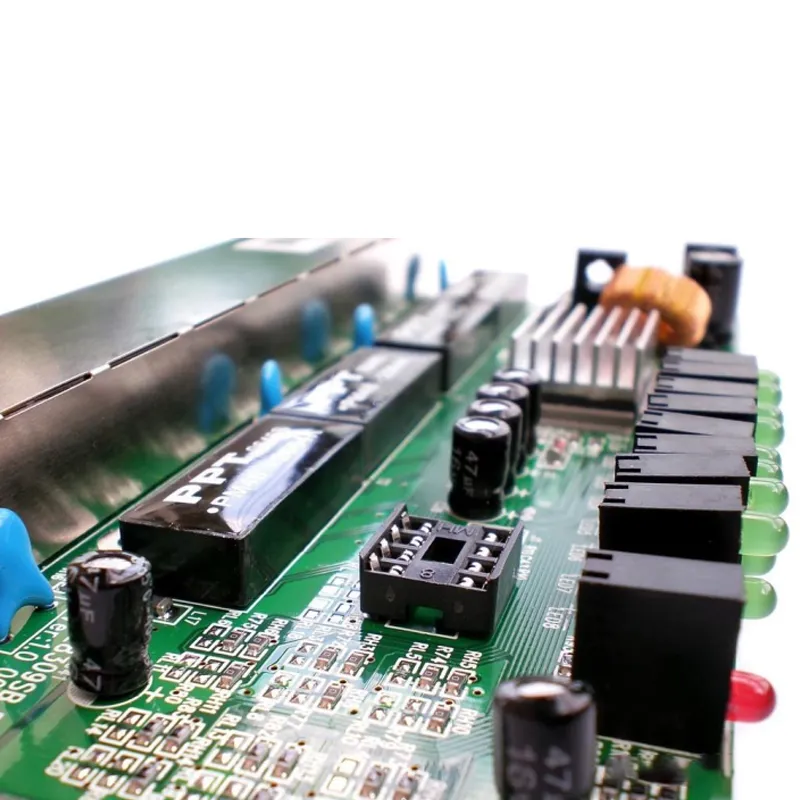

This chart or physical comparison diagram connects theoretical calculations (e.g., inductance value, peak current) with actual component parameters and performance. It may visually demonstrate how to make optimal choices based on specific application needs (current level, thermal management, EMI sensitivity) by comparing inductors of different specifications (e.g., EFD core vs. shielded drum core) and diodes of different packages (e.g., SS14, SS34 in various packages), emphasizing the importance of “margin” for reliability.

Inductor selection — L, Isat, DCR, and copper loss

The calculated inductance gives you a starting point, not a finish line. Say your math suggests 330 µH at 50 kHz. That value exists in dozens of shapes: radial chokes, shielded drum cores, molded SMD types. Which one works depends on your peak current and how much space you’re willing to give up.

A good rule of thumb:

- Pick Isat ≥ 1.3 × Ipk, or the core may saturate on load transients.

- Keep DCR < 0.3 Ω when possible; every 0.1 Ω adds roughly 50 mW loss at 0.5 A.

- Use ferrite for lower loss at high frequency; powdered iron tolerates current surges better.

For example, an EFD-core 330 µH inductor rated at 0.8 A may work fine on paper but will lose 15–20 % inductance at 80 °C. In practice, that shifts ripple and can destabilize the control loop. Shielded drum-core parts reduce EMI but cost slightly more — worth it if your converter sits near a radio or MCU clock trace.

Engineers often overlook one practical test: the “finger check.” If the inductor gets too hot to touch after five minutes at nominal load, you’re pushing it. Increasing wire gauge or switching to a core with higher (A_L) saves you long-term headaches.

Diode selection — VF, IF(avg/peak), IR, and thermal margin

For the Schottky diode, low forward drop and low reverse leakage rarely coexist perfectly. In a 12 V to 5 V buck, you’re usually switching around 50–150 kHz, so recovery time isn’t critical; what matters more is VF and average forward current.

Target:

- VF ≤ 0.5 V @ Iout to limit loss.

- IF(avg) ≥ Iout, and IF(peak) ≥ Ipk.

- Reverse leakage (IR) < 1 mA @ 25 °C keeps efficiency stable at light load.

Common choices include 1N5819, SS14, or MBR0540 families. For 1 A builds, move to SS24/SS34. Package thermals matter more than most datasheets imply — an SMA diode on FR-4 can run 15–20 °C cooler than an SOD-123 at equal current.

In real layouts, place the diode close to the switch node and output cap to shorten the high-di/dt loop. Long leads or vias increase ringing, forcing you to add snubbers later. If your EMI margin is tight, use an RC snubber (e.g., 100 pF + 10 Ω) across the diode; it costs a few milliwatts but can cut spectral spikes by 6–10 dB.

Finally, remember temperature coefficients: a diode rated 3 A at 25 °C may derate to 2 A at 80 °C. Always check that your expected thermal rise + ambient stays under its limit.

Real-world pairing examples

| Case | Inductor | Diode | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 to 5 V @ 0.5 A | 330 μH, 0.8 A Isat, 0.25 Ω DCR | SS14 (1 A avg) | Cool, quiet, low cost |

| 12 to 5 V @ 1 A | 150 μH, 1.5 A Isat, 0.15 Ω DCR | SS34 (3 A avg) | Runs ~15 °C cooler |

| 12 to 5 V @ 1 A (EMI-sensitive) | 150 μH shielded drum | MBR0540 (low VF) + snubber | Best for radio boards |

Choosing parts is about margin. If the datasheet says “maximum current = 1 A,” don’t plan to run it there continuously. The most reliable converters are those designed to look a little over-built.

For more grounding advice around fast current loops, refer to TEJTE’s layout piece on TVS/ESD placement near DC-DC—the same noise-return logic applies here.

Build your short BOM: what actually goes on the board?

Core components

- Controller IC — MC34063 or MC34063A. Choose SOIC-8 over DIP-8 for smaller layouts.

- Inductor (L) — 330–470 µH for ≤ 0.5 A; 150–220 µH for ≈ 1 A. Shielded drum type recommended.

- Diode (D) — SS14 to SS34 class; low-VF Schottky in SMA package.

- Input capacitor (Cin) — 100 µF electrolytic + 0.1 µF ceramic close to Vin pin.

- Output capacitor (Cout) — 100–220 µF low-ESR electrolytic + 1 µF ceramic.

- Rsc — 0.47 Ω ±5 %, ≥ 0.25 W metal film.

- Timing capacitor (Ct) — sets switching frequency. 330 pF to ≈ 100 kHz typical.

Together, they form the minimal circuit to deliver a clean 5 V rail at moderate loads.

Footprint and second-source notes

- Inductor: keep pads large; thermal relief can raise temperature by 5–8 °C if too narrow. Popular series like Murata LQH, Sumida CDRH, and Bourns SRR have drop-in equivalents.

- Diode: SMA and SMB footprints interchange easily; leave room for a heat-spreading copper pour.

- Capacitors: parallel one electrolytic with one X7R ceramic to cover both low- and high-frequency noise.

- Controller: MC34063A is pin-compatible but offers slightly higher oscillator frequency tolerance and lower bias current.

Even small layout changes affect EMI. The high-di/dt loop — from the switch pin through diode, inductor, and back to ground — should form the smallest possible triangle. Route the feedback trace away from this loop to avoid jitter. These are the same physical principles covered in the MC34063 calculator & limits reference, but worth re-stating here: good geometry beats fancy filtering.

Example BOM snapshot

| Ref | Component | Typical Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| U1 | MC34063ADR2G | Controller | 50-100 kHz switcher |

| L1 | 330 μH, 0.8 A Isat | Shielded drum | Core loss < 0.2 W |

| D1 | SS14 | 1 A avg Schottky | VF ≈ 0.45 V |

| C1 | 100 μF / 25 V + 0.1 μF | Input filter | Low ESR |

| C2 | 100 μF / 10 V + 1 μF | Output filter | Ripple < 50 mV |

| RSC | 0.47 Ω / ¼ W | Sense resistor | Sets current limit |

| Ct | 330 pF | Timing | ≈ 100 kHz |

| R1-R2 | Divider | Sets 5 V output | Ratio ≈ (1 + R1/R2) |

Assembly and testing tips

- Solder the diode and inductor last — they’re easiest to probe.

- Clip a thermocouple to the inductor during burn-in; 10 °C difference over ambient hints at potential core saturation.

- Measure ripple directly on the output capacitor with a short ground spring, not with long scope leads.

- Document efficiency across load steps; even crude sweeps (0.1 A to 1 A) tell you more than ideal equations ever will.

After building a few boards, patterns emerge. Hot diodes mean too little copper. Excess ripple hints at ESR drift. Slight buzzing around 50 kHz? That’s often the inductor’s magnetic gap talking — harmless unless it vibrates nearby parts.

By now, your 12 V to 5 V buck converter should be ready for layout optimization and EMI control, which we’ll cover next.

What layout rules keep noise and EMI under control?

You can calculate every value perfectly and still end up with a converter that squeals on the bench. Layout, not math, decides whether a 12 V to 5 V buck converter behaves quietly or becomes a miniature transmitter.

Start with the high-di/dt loop: switch to diode to inductor to ground. Keep that loop tight and short—a compact triangle, not a rectangle. The wider this loop, the larger your radiating antenna. Place the output capacitor so its ground joins the diode return at the same physical point. That single star junction minimizes common-mode noise.

The controller ground should connect separately to this star via a thin trace or single via. Mixing signal and power grounds in one pour almost guarantees ripple on the feedback pin. If you must pour copper, route it like rivers feeding one lake—narrow, converging, and predictable.

Here are practical spacing cues:

- Keep switch node area < 1 cm²; more copper equals more EMI.

- Keep inductor and diode close—ideally within 5–10 mm of each other.

- Use wide traces for high current, thin ones for sense and feedback.

- Avoid routing under the inductor; magnetic flux couples into traces underneath.

For extra stability, add a snubber (100 pF + 10 Ω) or a small RC damper from switch node to ground. You’ll lose a few milliwatts but gain quieter waveforms. A small ferrite bead (≈ 100 Ω @ 100 MHz) on the input lead can knock down ringing too.

If you ever wonder why two boards with identical schematics behave differently, look at their ground paths. On prototypes, use an oscilloscope probe with a ground spring directly at the diode-capacitor junction. You’ll see spikes vanish when loops are minimized.

Designers who work near radios or MCUs should also review the TVS/ESD placement near DC-DC reference—it explains how return currents from surge devices mirror those from the buck’s fast loops.

Validate your prototype: what must you measure first?

Once the solder cools, don’t just plug it in and hope. A quick validation routine catches 90 % of mistakes before they destroy your scope probes.

- Line and load sweeps.

Feed 9–15 V into the converter and watch output voltage. A properly compensated MC34063 design holds within ±3 %. Any droop or overshoot hints at incorrect inductor or feedback values.

- Ripple and noise spectrum.

Measure ripple directly at the output capacitor. With 100 µF + 1 µF ceramic, you should see ~35 mV p-p at 0.5 A. If it’s higher, check ESR or grounding. A quick FFT on the scope shows switching tone at 50–100 kHz and small harmonics—these must stay > 40 dB below the fundamental for clean EMC results.

- Peak current check.

Clip a current probe to the inductor. The waveform should ramp from Iout – ΔIL⁄2 to Iout + ΔIL⁄2 smoothly. Flat tops or double peaks indicate core saturation or unstable control.

- Efficiency curve.

Plot efficiency versus load. You’ll typically see ~78 % at 0.2 A and ~86 % near 0.8 A for an MC34063 design. Anything below that means diode VF or DCR losses are too high.

- Thermal observation.

During a 10-minute burn-in at full load, measure case temperature on diode, inductor, and IC. Keep each under 90 °C. Every 10 °C reduction roughly doubles life expectancy of nearby electrolytics.

If results differ wildly from theory, retrace your sense resistor and feedback network. Layout parasitics often add invisible milliohms that shift current limit thresholds. Cross-check against formulas from the MC34063 calculator & limits guide to confirm whether your observed current aligns with expected Ipk.

One often-missed test: cold start at low input. Drop Vin to 9 V and see if the converter still rises cleanly. Brownout conditions reveal weak diodes or borderline inductance faster than any simulation.

When should you not use this 12V to 5V buck approach?

There are times when the simple MC34063-style buck is the wrong tool, even if it technically works. Knowing when to walk away saves both cost and compliance trouble.

- Very low-noise systems.

Audio or precision-sensor circuits can’t tolerate tens of millivolts of ripple. A linear post-regulator or low-dropout LDO after the buck may help, but for ultimate quiet you’ll want an integrated synchronous converter with spread-spectrum control.

- High-efficiency or compact designs.

At 12 to 5 V / 1 A, asynchronous loss (≈ 0.45 V × 1 A × 0.54 duty ≈ 0.24 W) and switch saturation quickly eat your budget. MOSFET-based synchronous converters hit 92–94 % where MC34063 stays around 85 %. In battery-powered gear, that gap matters.

- Automotive or EMC-critical products.

The MC34063 lacks soft-start, UVLO precision, and EMI filtering required for automotive E-mark. Controllers like LT8608 or MP1584 offer built-in protections, higher frequency, and cleaner spectra.

- Tiny footprints.

If your board space forces SMD inductors below 100 µH, MC34063’s fixed frequency becomes inefficient. Switching to 1–2 MHz controllers cuts inductor size tenfold without heavy ripple penalties.

That doesn’t mean the old architecture is obsolete. For quick prototypes, education labs, or low-cost IoT nodes, it’s still a reliable foundation. It’s predictable, forgiving, and repairable—traits modern silicon sometimes lacks. As engineers often say: you can’t beat physics, but you can outsmart it with margin.

For broader context on how buck topologies evolved, see the concise overview on Wikipedia — Buck converter; it complements TEJTE’s hands-on guides by showing where these discrete designs fit in modern power ecosystems.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. How much peak current headroom should I leave in a 12V to 5V buck converter?

2. What ESR value helps keep output ripple under control without breaking stability?

3. Which has a bigger impact on efficiency — the diode’s forward drop or the inductor’s resistance?

4. Why does my MC34063 board heat up even with a small load?

5. How can I safely check if my layout’s high-di/dt loop is tight enough?

6. Can the MC34063 really supply 1 A continuously from 12 V to 5 V?

7. What part usually gives up first during brownouts or surge events?

Closing insight

Designing a 12 V to 5 V buck converter isn’t about chasing exotic efficiency numbers; it’s about building something that keeps running for years without surprises. From first equations to thermal burn-in, every step tells you how close theory meets the bench.

TEJTE’s DC-DC content cluster—spanning layout, surge control, and component selection—exists to shorten that learning curve. Pair this guide with resources like the MC34063 calculator & limits and the TVS/ESD placement near DC-DC note, and you’ll have a full framework for turning a schematic into a stable production-ready power stage.

The math keeps you honest, but the layout—and a bit of engineering intuition—makes it survive the real world.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.