BNC to SMA Adapter Usage and Selection Guide

Feb 08,2026

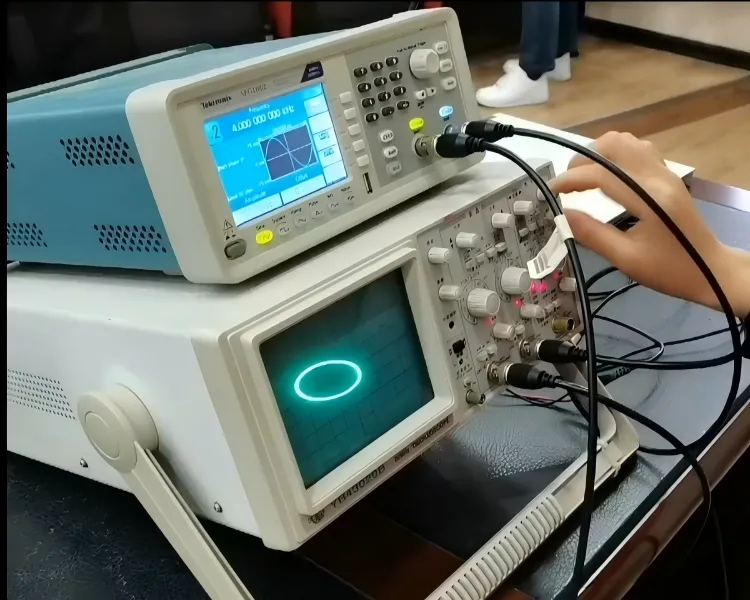

This figure is placed at the beginning of the guide, introducing the physical form of the BNC to SMA adapter. It serves as a visual anchor for the discussion on how this seemingly simple mechanical component functions as a critical, yet often overlooked, boundary between different connector ecosystems in an RF signal chain. The guide emphasizes that while adapters rarely cause immediate failure, they can subtly degrade system margin over time.

Map where a BNC to SMA adapter actually fits in your RF chain

Identify common BNC-to-SMA transitions in labs, CCTV, and RF test setups

In laboratory environments, BNC connectors are often inherited rather than chosen. Pulse generators, timing references, legacy signal sources, and low-frequency instruments still rely on BNC because it was designed for quick mating and mechanical robustness long before multi-gigahertz bandwidth became routine. SMA connectors, on the other hand, dominate modern RF instruments, DUT interfaces, and antenna paths. The transition usually appears when an older source is asked to interface with a newer measurement chain, not because it was planned, but because the hardware already exists.

CCTV and broadcast systems introduce a different pattern. Here, BNC is not legacy—it is deliberate. It supports long cable runs, frequent reconnects, and field service. SMA typically enters only during diagnostics or monitoring, where portable RF tools or analyzers are temporarily inserted into a video chain. Embedded systems sit somewhere between these worlds. Evaluation boards expose SMA ports for clean measurements, while production fixtures and test harnesses often favor BNC for durability. In all three cases, the adapter is solving a real integration problem, but the electrical expectations behind each use case are very different.

Separate “temporary adapter” use from “permanent inline” use

One of the most practical distinctions you can make is whether the adapter is meant to be touched again. Temporary adapters live on benches. They are connected and disconnected dozens or hundreds of times, rotated to relieve cable stress, and occasionally swapped mid-measurement. In that context, mechanical repeatability and ease of handling matter as much as absolute RF performance. A slightly higher insertion loss is often acceptable if the connection behaves the same way every time it is mated.

Permanent inline adapters behave more like hidden components. Once installed in a rack, enclosure, or panel feedthrough, they may remain untouched for years. In that role, small impedance errors and marginal plating quality become long-term reliability risks rather than short-term inconveniences. These adapters don’t usually fail catastrophically. Instead, they show up later as increased sensitivity to vibration, unexplained calibration drift, or links that degrade only under specific environmental conditions. Treating temporary and permanent use cases as interchangeable is one of the most common causes of adapter-related issues.

Distinguish 50 Ω RF paths from 75 Ω video paths before adapting

This figure illustrates the 50-ohm variant of the BNC connector. It is presented in the section discussing the critical importance of distinguishing between 50-ohm and 75-ohm BNC types before using an adapter. The 50-ohm BNC is commonly used in RF test equipment and systems where impedance matching at higher frequencies is essential to minimize signal reflections.

This figure shows the 75-ohm variant of the BNC connector, placed in direct contrast to Figure 2. It highlights a common pitfall: visually identical BNC connectors can have different electrical impedances. The 75-ohm type is standard in video, CCTV, and broadcast infrastructure. Using it with a standard 50-ohm SMA adapter or instrument will create an impedance mismatch, potentially degrading signal integrity, especially at higher frequencies.

Visually, most BNC connectors look the same. Electrically, they are not. BNC exists in both 50-ohm and 75-ohm variants, while SMA is almost universally 50 ohms. When a 75-ohm video path is adapted into a 50-ohm measurement instrument, the signal does not suddenly disappear. That’s what makes the mistake easy to miss. The system continues to function, but reflections increase and return loss degrades. At low frequencies, the effect is often negligible. As bandwidth increases, margin disappears quickly.

This is especially relevant in mixed environments where RF diagnostics are performed on video infrastructure. If the impedance assumptions of the BNC side are unclear, the adapter becomes a silent source of measurement error rather than a neutral bridge. Engineers who work regularly with these transitions often keep separate, clearly labeled adapters for 50-ohm and 75-ohm paths to avoid accidental cross-use. A more detailed discussion of how cable and connector impedance choices affect different signal types can be found in the BNC Cable Selection Guide for Video, CCTV, and RF Test, which explains why some systems tolerate mismatch longer than others.

When should you use a BNC to SMA adapter instead of building a new cable?

Compare cost, lead time, and reliability between adapters and custom cables

Adapters excel when time matters. They are off-the-shelf, inexpensive, and immediately reusable across multiple projects. When a setup needs to work today, an adapter is often the only realistic option. Custom cables, by contrast, require specification, ordering, and lead time. That investment makes sense when the connection will remain unchanged for a long period, but it slows iteration during early development or troubleshooting.

Reliability is more nuanced than it first appears. A short adapter introduces a single additional interface. A cable assembly introduces two connectors plus cable attenuation. In short runs, especially on benches, a high-quality adapter can be electrically cleaner than a poorly specified or excessively long cable. Problems arise not because adapters are inherently unreliable, but because their role is misunderstood.

Decide for RF benches: flexible reconfiguration vs fixed test harness

On RF benches, flexibility usually outweighs optimization. DUTs change, instruments move, and routing evolves as measurements progress. Locking everything into a fixed harness too early often slows debugging rather than improving accuracy. This is why many experienced labs standardize on BNC at the instrument side and adapt closer to the DUT, where changes are easier to manage.

Once a setup stabilizes—such as in production testing or compliance verification—the priorities shift. Repeatability and reduced wear become more important than flexibility. At that point, replacing adapters with dedicated cable assemblies often improves long-term consistency. The adapter has not failed; it has simply outlived its purpose.

Decide for CCTV and broadcast: field service needs vs signal margin

Field environments prioritize speed and interchangeability. Technicians need to diagnose faults quickly without rebuilding infrastructure, and adapters make that possible. At the same time, long video runs operate with limited margin, and every discontinuity matters. For this reason, adapters are commonly used during diagnostics and removed once the issue is identified.

If the limiting factor turns out to be on the SMA side—such as connector quality, mounting style, or frequency capability—it is often more effective to revisit that interface directly rather than stacking additional transitions. A practical overview of how SMA connectors influence RF cable and antenna behavior is covered in the SMA Connector Selection for RF Cables and Antennas, which complements the adapter discussion by addressing the endpoint itself.

Compare BNC to SMA adapter options for lab, field, and embedded use

Use a BNC to SMA adapter in RF test benches and spectrum analyzers

This figure depicts a BNC to SMA adapter being used in a typical RF test bench or spectrum analyzer setup. The surrounding text explains that in such environments, adapters are part of the dynamic workflow—frequently handled, connected, and disconnected. Therefore, their mechanical durability, repeatability, and ease of handling are as important as their electrical specifications. The figure underscores the real-world context where adapters face wear and varying signal conditions.

On RF benches, adapters are part of the workflow rather than part of the product. They are handled constantly, often under time pressure, and sometimes by people who did not set up the original measurement. In that context, mechanical behavior matters as much as electrical behavior. An adapter that loosens slightly when a cable is rerouted can introduce enough variability to undermine otherwise careful measurements, even if its nominal RF rating looks fine on paper.

Another factor that shows up on benches is frequency spread. The same adapter may see low-frequency pulse testing in the morning and multi-gigahertz sweeps in the afternoon. That mixed use favors conservative designs with stable geometry over compact or lightweight styles. Many labs eventually narrow their inventory down to a few adapters that “behave predictably,” not because they are perfect, but because their quirks are known. Everything else quietly disappears from circulation.

Use a BNC to SMA adapter in CCTV video diagnostics and monitoring

CCTV environments impose different pressures. Here, adapters are usually introduced during troubleshooting rather than normal operation. They sit temporarily in long cable runs that were never designed to be disturbed, and the goal is observation rather than optimization. The danger is assuming that a temporary diagnostic connection is electrically neutral. It rarely is.

Because video systems are often built around BNC interfaces by design, the adapter becomes the point where RF-style assumptions collide with video-style impedance expectations. Signals may still look acceptable on a monitor while being measurably distorted at the diagnostic instrument. That gap between “it looks fine” and “it measures clean” is where misinterpretation happens. Engineers who spend time in these environments tend to treat adapters as measurement artifacts, not invisible links, and remove them as soon as the test is complete. The historical reasons BNC evolved this way, particularly its parallel 50-ohm and 75-ohm ecosystems, are outlined succinctly in the background material on BNC connectors, which helps explain why these mismatches are so common in the field.

Use a BNC to SMA adapter in embedded RF modules and evaluation boards

Embedded systems are usually where adapter weaknesses show up fastest. Evaluation boards often expose SMA connectors that were never meant to carry the mechanical load of cables, let alone adapters plus cables. Adding a straight, rigid adapter increases leverage at the connector interface, and over time that stress migrates into solder joints or PCB pads.

Right-angle and bulkhead styles exist largely to manage this problem, not to improve RF performance. By redirecting forces or anchoring the transition to a panel, they reduce mechanical strain at the board level. Electrically, embedded designs also tend to operate closer to their margins, so small impedance disturbances that are irrelevant on a bench can translate into reduced link budget or intermittent behavior in real use. Adapter choice in this context is less about convenience and more about minimizing unknowns.

How do you keep impedance and return loss under control at the transition?

Match 50 ohm BNC cable to 50 Ω SMA ports and avoid 75 Ω surprises

Check datasheet specs: VSWR / return loss across frequency

Adapters that matter publish meaningful RF data. VSWR or return-loss specifications across frequency bands provide insight into how the transition behaves as wavelengths shrink. When specifications stop well below the operating band, the adapter becomes an unknown quantity. In controlled measurement environments, unknowns are often more disruptive than known limitations.

Understanding why some connector geometries maintain return loss better than others becomes clearer once you look at how SMA connectors were designed to scale into higher frequencies. A concise technical overview is available in SMA connectors, which explains why SMA displaced older interfaces in RF measurement chains.

Estimate total path loss: cable attenuation + adapter loss + connector wear

Choose BNC to SMA adapter gender, orientation, and body style

This figure shows a specific gender configuration: a BNC male plug to an SMA female jack adapter. It is presented in the section dedicated to selecting adapter gender, orientation, and body style. The guide clarifies that distributor naming conventions can be confusing, and physically verifying connector ends is the most reliable method. This image aids in visual identification of this common adapter type.

This figure illustrates the opposite gender configuration from Figure 5: an SMA male plug to a BNC female jack adapter. Alongside Figure 5, it helps users distinguish between the two primary gender combinations. The accompanying text advises teams to standardize on a small set of preferred adapter variants to reduce errors and friction in shared lab or field environments.

Match bnc to sma adapter vs sma to bnc connector wording on distributors

Select sma female to bnc male adapter vs sma male to bnc female adapter

Decide between in-line, right-angle, and bulkhead adapter bodies

BNC to SMA Adapter Selection Matrix

| Application scenario | Port A connector | Port A gender & impedance | Port B connector | Port B gender & impedance | Frequency range | Max RF power | Orientation | Recommended adapter description | Adapter loss | Estimated total path loss | Risk notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF lab bench | BNC | Female 50 Ω | SMA | Male 50 Ω | DC–3 GHz | 10 W | Straight | SMA male to BNC female adapter | ~0.15 dB @ 3 GHz | Cable loss + adapter | Stable for bench work |

| CCTV diagnostics | BNC | Female 75 Ω | SMA | Female 50 Ω | <300 MHz | <1 W | Straight | BNC female to SMA female adapter | N/A | Cable dominant | Reflection expected |

| Embedded testing | BNC | Male 50 Ω | SMA | Female 50 Ω | DC–6 GHz | 5 W | Right-angle | BNC male to SMA female adapter | ~0.2 dB @ 6 GHz | Cable + adapter | Reduced board stress |

How do you plan frequency, power, and durability for repeated connections?

Check adapter frequency rating vs your instrument and DUT bandwidth

Frequency ratings on adapters are often read as absolutes, but they behave more like confidence envelopes. An adapter rated to 3 GHz may still pass signal at 4 or 5 GHz, but what changes is how sensitive the system becomes to everything else. Cable routing matters more. Connector alignment matters more. Small mechanical shifts begin to show up as measurable changes.

This is why adapters that are used across a wide range of tests tend to age poorly. The same physical interface may be exposed to very different wavelengths, and geometry that is benign at low frequency becomes critical as frequency rises. Engineers who care about repeatability usually avoid pushing adapters near their upper frequency limits, not because failure is guaranteed, but because predictability is not.

Estimate power and voltage limits for RF vs video vs pulse signals

Power handling is another area where assumptions creep in. Continuous RF power stresses connectors thermally. Pulsed or fast-edge signals stress them electrically, often in ways that are harder to observe. Video paths tend to operate at low power but over long durations, while RF test setups may see short bursts of significantly higher power.

Adapters that survive one regime may degrade silently in another. A connector that never overheats can still suffer from plating erosion or micro-arcing under repeated high-voltage transitions. When adapters are shared between RF and pulse work, these effects accumulate invisibly until behavior changes. Separating adapters by signal class is often less about protection and more about preserving trust in the measurement.

Plan for mating cycles and mechanical wear in high-usage labs

Mechanical life is where adapters most often reach the end of their usefulness. BNC interfaces tolerate frequent mating well, which is one reason they remain popular in bench environments. SMA interfaces, while excellent electrically, are less forgiving mechanically. Introducing an adapter shifts wear patterns, sometimes concentrating stress in places the original connector was not designed to handle.

In busy labs, adapters may see hundreds or thousands of mating cycles per year. At that point, wear is not hypothetical. Contact resistance drifts. Center pins lose alignment. The adapter still “works,” but not the same way it did before. Teams that rely on consistent results often track adapter usage informally, retiring pieces that feel loose or behave inconsistently even if no visible damage is present.

Avoid hidden failure modes with stacked adapters and cheap parts

Recognize issues: wobble, intermittent contact, and noisy measurements

A stable adapter disappears into the background. A problematic one attracts rules: don’t touch the cable, don’t bump the bench, don’t reroute during a sweep. Those rules are signals. If measurements change when a cable is nudged or rotated, the adapter is no longer neutral.

Noise introduced this way often masquerades as system instability. Engineers chase grounding, shielding, or software explanations while the mechanical interface quietly undermines confidence in the data. Recognizing this pattern early saves time.

Avoid adapter stacks: bnc to sma adapter + sma to bnc connector chains

Stacked adapters amplify every small imperfection. Each interface introduces its own tolerance, its own wear, and its own opportunity for misalignment. Electrically, the effects add. Mechanically, leverage increases. The result is a connection that behaves differently every time it is touched.

Adapter stacks usually appear when inventories are unmanaged. Someone solves a short-term problem by adding “just one more” transition. Over time, those temporary fixes become permanent. Replacing stacks with a single, purpose-matched adapter almost always improves stability, even if the nominal specifications look similar.

Spot counterfeit or low-grade adapters and qualify trusted sources

Low-grade adapters rarely fail immediately. Instead, their plating wears faster, their tolerances drift, and their behavior becomes inconsistent across temperature or handling. By the time this is obvious, they’ve often contaminated multiple measurements.

Many labs quietly converge on a short list of trusted sources, not because others are unusable, but because predictability matters more than price at this level. Once an adapter has proven itself across months of use, it tends to stay in rotation long after cheaper alternatives have been discarded.

Document, test, and maintain BNC to SMA adapters across projects

Label adapters by impedance, frequency class, and typical use case

Build a small acceptance test plan for new adapter batches

Retire damaged adapters and keep a known-good reference piece

FAQ

Can I use a 50 Ω BNC to SMA adapter in a 75 Ω CCTV video chain?

Yes, but only with clear expectations. The signal will pass, but reflections are unavoidable. For short diagnostic use, this may be acceptable. For permanent installation, it usually isn’t.

How much accuracy do I lose at 3 GHz if I stack multiple adapters?

There is no single number. What increases is variability. Each added interface raises sensitivity to alignment, cable movement, and wear, which degrades repeatability more than absolute accuracy.

Is a BNC to SMA adapter weatherproof enough for outdoor antenna testing?

Most are not designed for prolonged outdoor exposure. Temporary outdoor use is common, but long-term installations should use sealed connectors or enclosure-mounted transitions.

What is the difference between an adapter and a cable assembly?

An adapter changes interface geometry without adding cable length. A cable assembly adds two connectors and distributed loss. Which is better depends on whether flexibility or stability is the priority.

How often should adapters be replaced in a busy RF lab?

There is no fixed schedule. Replacement usually follows behavior, not time. When measurements become sensitive to handling, the adapter has likely reached the end of its useful life.

Can one adapter cover both low-frequency pulse testing and multi-GHz RF measurements?

It can, but it often shouldn’t. Separating adapters by signal class preserves predictability and reduces cumulative wear effects.

Do I need separate adapters for 50 Ω and 75 Ω applications?

In mixed environments, yes. Physical separation or clear labeling prevents accidental mismatch and saves time during troubleshooting.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.