MMCX to SMA Adapter Choices for RF Modules

Feb 03,2025

As the article's introduction, Figure 1's context describes how connector decisions in compact RF hardware often lag, creating a mismatch between modules (using MMCX) and the external ecosystem (using SMA). Therefore, this figure is likely a comparative schematic or infographic. The left side might show a typical "Compact RF Module" (e.g., GNSS or IoT module) with a close-up of its "MMCX" port. The right side could depict equipment like a "Spectrum Analyzer," "SMA Test Cable," or "External Antenna," highlighting their "SMA" interfaces. A question mark or dashed line between them visually introduces the core theme: the "MMCX to SMA Adapter" as the bridge across this interface gap.

In compact RF hardware, connector decisions almost always arrive later than they should.

By the time an engineer notices that a radio module exposes an MMCX connector, the antenna has already been selected, the enclosure outline is mostly fixed, and the test setup assumes an SMA interface by default.

That mismatch is where the mmcx to sma adapter enters the system—not as a design choice, but as a problem solver.

At first glance, adapting MMCX to SMA looks harmless. Both interfaces are 50-ohm. Signals pass. Early measurements look fine.

But experienced RF engineers know this transition point often becomes the quiet source of instability: drifting GNSS SNR, inconsistent RSSI, or results that change when the cable is touched or rotated.

This article focuses on how MMCX–SMA transitions actually behave in real RF systems, not just on paper. We’ll look at where they appear, how connector specs constrain adapter choices, and why mechanical details matter just as much as electrical ones.

If you’re already working with MMCX-based modules, this guide builds naturally on broader RF connector principles discussed in the RF connector selection guide, narrowing the focus to one of the most common—and most underestimated—adapter paths.

Clarify where an MMCX to SMA adapter fits in RF systems

Map typical RF module scenarios that expose MMCX ports

MMCX connectors appear most frequently on compact RF modules where board space is limited and repeated mating is expected during development.

Common examples include:

- GNSS positioning modules

- Cellular IoT radios (LTE Cat-M, NB-IoT, sub-6 GHz 5G modules)

- Wi-Fi and Bluetooth combo modules

- RF evaluation boards intended for quick antenna swaps

The mmcx connector works well here because it is small, snap-on, and allows limited rotation after mating. That rotational freedom reduces torsional stress when routing an mmcx cable inside a small enclosure, especially compared to fixed micro-coax interfaces.

For short internal runs, this is an advantage. The problem begins when that same MMCX port must interface with the outside world.

Identify SMA cable and test equipment that expect SMA interfaces

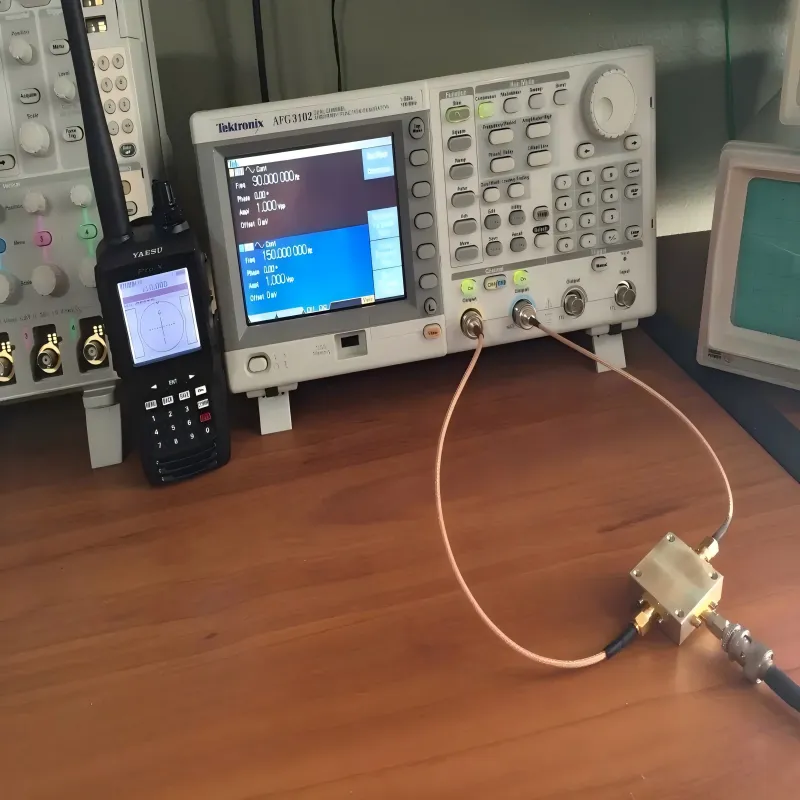

Figure 2 appears after the paragraph explaining "Outside the module, SMA dominates." The context lists spectrum analyzers, VNAs, test cables, etc., all standardizing on SMA. Therefore, this figure is most likely an image depicting a typical RF workbench or test setup. It would centrally feature key equipment: a "Spectrum Analyzer" or "Vector Network Analyzer" with multiple SMA ports on its front panel; several "SMA Cable Assemblies" and "SMA Jumpers"; possibly an "RF Shield Box" or "Attenuator" also fitted with SMA connectors. This image aims to emphasize the ubiquity of SMA in the industry, explaining why transitioning from a module's MMCX to SMA is an inevitable and common requirement.

Outside the module, SMA dominates.

Most RF ecosystems are built around:

- sma cable assemblies

- sma rf cable jumpers for test benches

- sma coax cable feeds to external antennas

Spectrum analyzers, VNAs, RF shield boxes, attenuators, and antenna fixtures are all standardized around SMA. Even when the RF module itself uses MMCX, the rest of the system rarely does.

This creates a natural fault line in the signal path: MMCX on the module, SMA everywhere else.

That’s exactly why the mmcx to sma adapter becomes a default solution—bridging a compact internal interface to a standard external RF ecosystem.

Position MMCX to SMA adapter versus other between-series adapters

Between-series adapters are common in RF work, but not all of them solve the same problem.

Adapters like MMCX-to-BNC or U.FL-to-SMA often exist to connect test equipment or evaluation boards. The mmcx to sma connector, however, tends to serve a more structural role: turning a module-level interface into a system-level RF port.

Compared with U.FL, MMCX offers better durability and mating life. Compared with MCX, it’s smaller and more tolerant of rotation. Pairing MMCX with SMA therefore becomes a practical compromise between compact module design and standardized RF connectivity.

This same design pattern appears repeatedly in systems that already rely on SMA infrastructure, such as those discussed in the SMA connector design guide.

How do MMCX and SMA connector specs constrain your adapter choice?

Compare mechanical classes: MMCX connector vs SMA connector

From a mechanical standpoint, MMCX and SMA live in different worlds.

The mmcx connector is:

- Snap-on rather than threaded

- Compact, with limited contact area

- Designed for moderate retention force

- Tolerant of limited rotation after mating

SMA, by contrast, is:

- Fully threaded

- Designed to handle higher axial and torsional loads

- More forgiving of cable weight and repeated handling

When a rigid mmcx to sma adapter is plugged directly into a PCB-mounted MMCX jack, any force applied to the SMA side—tightening, cable pull, or vibration—is transmitted straight into the module connector.

Electrically, this may be fine. Mechanically, it’s where long-term reliability starts to erode.

This is why many engineers prefer flexible transitions for production designs, even if rigid adapters seem acceptable during early lab work.

Check frequency rating, VSWR, and power handling limits

Most commercial mmcx to sma adapter products are specified up to 6 GHz. That comfortably covers:

- GNSS L-band

- 2.4 GHz and 5 GHz Wi-Fi

- Many sub-6 GHz cellular bands

Higher-quality adapters may advertise tighter VSWR limits—often around 1.25 or better across their rated band. That matters in systems where every fraction of a dB counts, such as GNSS receivers or high-order modulation links.

Insertion loss per adapter is typically small (often quoted between 0.1 and 0.3 dB), but those losses add up quickly once multiple transitions are chained together.

Power handling is rarely the limiting factor for MMCX–SMA links in module-to-antenna paths. These adapters are intended for signal-level RF, not high-power transmission lines.

Evaluate material, plating, and temperature range

Construction details vary more than many datasheets suggest.

Common variations include:

- Gold-plated brass bodies

- Stainless-steel housings for added durability

- Standard versus extended temperature ratings

In a temperature-stable lab, these differences may never show up. In automotive, industrial, or outdoor-adjacent enclosures, they often do. Plating quality, in particular, affects long-term contact stability after repeated mating cycles.

These considerations mirror broader adapter selection challenges discussed in articles like the MMCX cable routing guide for RF modules, where mechanical context often matters more than nominal electrical specs.

Choose between MMCX to SMA adapters, pigtail cables, and panel transitions

Once you accept that an MMCX–SMA transition is unavoidable, the real question shifts.

Not whether to adapt, but how much mechanical responsibility you want that connection to carry.

This is where many RF designs quietly diverge.

When should you prefer a rigid MMCX to SMA adapter block?

Figure 3 appears in the chapter comparing rigid adapters vs. flexible cable assemblies, with its title directly stating “图3 MMX Female to SMA Female Adapter”. Therefore, this figure is undoubtedly a close-up image of a rigid barrel adapter. It is likely a product photo or clean 3D render showing a small metallic cylinder with an “MMCX Female” (snap-on) end and an “SMA Female” (threaded) end. The image might include wireframe diagrams or arrows indicating how this rigid structure would transmit torque or pull forces from an attached SMA cable directly to the PCB-mounted MMCX jack. This visualizes the dual nature of this solution: electrically clean but mechanically risky.

A rigid mmcx to sma adapter is tempting because it feels clean. No extra cable. No routing decisions. No strain relief planning.

In practice, these adapters behave best in environments where nothing moves.

Typical examples:

- Bench measurements

- Early RF bring-up

- Temporary antenna swaps during tuning

In those cases, the adapter acts as a short electrical bridge. You plug it in, take measurements, and move on.

The problem is not electrical. It’s mechanical.

Once a sma rf cable is attached, the MMCX jack becomes the only thing resisting torque, cable stiffness, and accidental rotation. The adapter itself doesn’t fail. The mmcx connector underneath it slowly takes the abuse.

You won’t see this on day one.

You’ll see it weeks later, when touching the cable changes readings.

When does an MMCX cable assembly with RG316 coaxial cable make more sense?

The context title for Figure 4 is “SMA Male to MMCX Female with RG316 Cable,” following the paragraph discussing “the moment a product leaves the lab, flexibility starts to matter more than elegance.” Therefore, this figure is certainly an illustration of a flexible cable assembly. It would clearly show a thin, flexible “RG316 Coaxial Cable” with an “MMCX Female” connector on one end (for the module) and an “SMA Male” connector on the other (for external cables/interfaces). The image might highlight its “flexibility” by showing the cable in a bent state and use annotations to emphasize its core advantage: absorbing stress through cable flex to “isolate the module from mechanical stress” and protect the fragile MMCX jack. This is the key contrast to the rigid solution in Figure 3.

The moment a product leaves the lab, flexibility starts to matter more than elegance.

An mmcx cable assembly built with rg316 coaxial cable introduces one extra variable—cable loss—but removes a much bigger risk: direct mechanical loading on the module connector.

RG316 shows up in these designs for boring reasons:

- It bends easily

- It tolerates heat better than many micro-coax options

- Its loss is predictable and well documented

Electrically, it’s not perfect. Mechanically, it’s forgiving.

In systems where the antenna cable might be nudged, rerouted, or reconnected by someone who isn’t thinking about RF, that forgiveness is often the difference between “works” and “works reliably.”

How should you combine MMCX, SMA, and panel connectors in a product?

Figure 5 is directly titled “MMCXPigtailCable.” Its context (Page 10) discusses combining MMCX, SMA, and panel connectors in a product, stating that “most production designs eventually converge on the same compromise” using a “short mmcx cable” as a bridge. Therefore, this figure is most likely a product close-up or clear schematic of an “MMCX to SMA Pigtail Cable.” The image would focus on the cable’s two key ends: one is an MMCX Female Connector (for plugging into the module’s MMCX male jack), and the other is an SMA Male Connector (for connecting to an SMA female bulkhead connector on the enclosure panel or to an external cable). Connecting them is a segment of flexible coaxial cable (RG316 is mentioned in the text). This figure aims to visually present this crucial component that acts as a “mechanical buffer,” the physical embodiment enabling the “division of labor” between the fragile internal interface and the robust external one.

Most production designs eventually converge on the same compromise.

The MMCX stays inside.

The SMA lives on the enclosure.

A short mmcx cable bridges the two.

This layout lets the SMA interface absorb everything it was designed to handle: tightening torque, cable weight, repeated mating cycles. The MMCX connector, by contrast, only sees a lightweight, flexible load.

That division of labor matches the original intent behind both connector families, as outlined in general references like the SMA connector overview on Wikipedia.

When designers skip this step and route a full-length sma coax cable directly from the MMCX jack, failures tend to be delayed rather than immediate—which makes them harder to trace.

How should you plan mechanical retention and strain relief for MMCX to SMA links?

RF simulations don’t warn you when a connector is about to loosen.

Mechanical planning fills that gap.

Control cable bend radius and routing near the RF module

Most MMCX-related issues start very close to the connector body.

Sharp bends, forced routing, or cables pressed against enclosure walls all concentrate stress where the mmcx cable meets the module. Over time, that stress changes contact behavior even if nothing visibly breaks.

With rg316 coaxial cable, a slightly longer loop near the module often outperforms a tight, “neat-looking” route. It’s not pretty. It’s reliable.

Add strain relief for SMA cable and adapter combinations

On the SMA side, gravity matters more than people expect.

A hanging sma cable exerts constant rotational force. Without a clamp or anchor point, that force travels backward through the adapter or pigtail and ends up at the MMCX interface again.

Simple mechanical fixes—clips, tie points, adhesive mounts—often stabilize RF performance more effectively than changing cable type.

Mitigate vibration and repeated handling in field installations

In vehicles, industrial equipment, or portable devices, vibration turns small weaknesses into repeatable failures.

Under those conditions:

- Rigid adapters age poorly

- Short flexible transitions age better

- Panel-mounted SMA interfaces age best

This isn’t theory. It aligns closely with the mechanical limits described in general summaries like the MMCX connector reference on Wikipedia, which emphasize that MMCX was never intended to carry sustained external loads.

If the connector has to move, let the cable move—not the jack.

What this means in practice

By this stage of the design, most engineers reach the same conclusion—even if reluctantly.

Rigid mmcx to sma adapter blocks are fine for the bench.

Flexible mmcx cable assemblies belong in real products.

SMA bulkheads belong on enclosures, not PCBs.

The sooner that decision is made, the fewer “mystery RF issues” show up later.

Estimate loss and frequency limits for MMCX to SMA signal paths

At some point, intuition stops being useful.

Once adapters, pigtails, and bulkheads start stacking up, you need a simple way to decide whether a signal path is still viable.

This is where a lightweight loss and margin model earns its keep.

MMCX–SMA Path Loss & Margin Calculator

The goal here isn’t precision down to the third decimal. It’s clarity.

Inputs

• cable_type

Examples: rg316 coaxial cable, RG178, other 50-ohm micro coax

• center_freq_GHz

Typical values: 1.575 (GNSS L1), 2.4, 5.8

• length_cm

Total cable length between MMCX and SMA

• cable_loss_dB_per_m

Taken from the datasheet of the selected sma rf cable or micro-coax

• adapter_loss_dB

Typical range for one mmcx to sma adapter: 0.1–0.3 dB

• num_adapters

Between-series transitions in the path

• target_budget_dB

Maximum allowable loss for the RF link

Intermediate calculations

• cable_loss_total_dB = cable_loss_dB_per_m × (length_cm ÷ 100)

• adapter_loss_total_dB = adapter_loss_dB × num_adapters

Outputs

• total_path_loss_dB = cable_loss_total_dB + adapter_loss_total_dB

• margin_dB = target_budget_dB − total_path_loss_dB

- Result: PASS if margin ≥ 0, otherwise FAIL

This simple structure is often enough to prevent over-engineering—or worse, underestimating loss until it shows up in testing.

Collect loss data for RG316 and other SMA RF cables

Manufacturers usually publish attenuation figures at a few discrete frequencies. For rg316 coaxial cable, loss rises quickly above 2–3 GHz, which is why short runs matter.

When exact frequency data isn’t available, engineers typically interpolate conservatively rather than optimistically. That habit saves time later.

If you’re already comparing cable options, it helps to reference broader guidance on attenuation versus length, such as those discussed in the SMA coax cable selection guide.

Apply the calculator to common GNSS, Wi-Fi, and 5G bands

Consider a GNSS module with:

- PCB-mounted mmcx connector

- 10 cm RG316 pigtail

- One mmcx to sma connector

- External antenna via SMA bulkhead

At L-band, the loss is usually modest.

Stretch that pigtail to 30 cm or add another adapter, and margin disappears faster than expected.

Running these scenarios early avoids late surprises when antenna performance suddenly looks worse than the datasheet promised.

Use margin results to drive design decisions

When margin turns negative, the fixes are rarely mysterious:

- Shorten the mmcx cable

- Switch to a lower-loss cable type

- Remove unnecessary between-series adapters

What matters is making the decision before enclosure tooling and harness lengths are frozen.

Verify MMCX to SMA connections during prototyping and production test

Perform basic continuity and “wiggle” checks on MMCX cable assemblies

A simple but revealing test:

While monitoring RSSI, SNR, or EVM, gently move the mmcx cable near the connector.

Stable readings suggest healthy contact. Fluctuations often point to marginal mating or early wear—long before outright failure.

Use a VNA or spectrum analyzer to validate adapters and cables

From the SMA side, testing becomes straightforward.

Using a sma cable to connect into a VNA allows quick checks of:

- Return loss (S11)

- Insertion loss (S21)

Adapters that look identical mechanically often behave very differently electrically. This step filters out weak links early.

For teams building repeatable test setups, this practice aligns well with the broader testing philosophy outlined in guides like the SMA to BNC adapter selection article.

Set acceptance criteria for production EOL testing

Production testing benefits from clear limits:

- Maximum allowable insertion loss at target bands

- Minimum return loss or maximum VSWR

- Visual inspection rules (plating wear, deformation, locking feel)

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s consistency.

Track industry updates that may change MMCX to SMA adapter selection

Monitor new high-frequency and high-temperature MMCX–SMA adapters

Some manufacturers are tightening tolerances and improving plating to support:

- Lower VSWR

- Higher operating temperatures

- Better repeatability at upper sub-6-GHz bands

These refinements matter more for test environments than for basic connectivity, but they’re worth tracking if your designs operate near margin limits.

Watch supply chain changes for RF adapter brands

Availability shifts faster than specifications.

When a particular mmcx to sma adapter becomes hard to source, redesign pressure follows. Qualifying a second source early avoids last-minute compromises.

Follow trends in RF module connectors for IoT and GNSS devices

Frequently asked engineering questions

Can I use an MMCX to SMA adapter at 6 GHz for Wi-Fi 6E or 5G testing?

Often yes, provided the adapter is specified for that range and maintains acceptable VSWR. Margin matters more than the headline frequency rating.

Is an MMCX to SMA pigtail more reliable than a rigid adapter under vibration?

In most cases, yes. A short mmcx cable isolates the module from mechanical stress far better than a rigid block adapter.

How much loss does a typical MMCX to SMA adapter add at 2.4 GHz?

Common values fall between 0.1 and 0.3 dB. The exact figure depends on construction quality and mating condition.

Will repeated mating cycles damage the MMCX connector on my RF module?

Over time, yes. Using an intermediate adapter or sacrificial cable during testing reduces wear on the module jack.

Can I route MMCX to SMA RF cables alongside digital harnesses?

It’s possible, but separation and grounding matter. Poor routing often shows up as noise long before complete failure.

Are MMCX to SMA adapters suitable for outdoor antenna installations?

Most are not weather-sealed. Outdoor use typically requires an enclosure-mounted SMA interface with proper sealing.

Final perspective

The mmcx to sma adapter is rarely the star of an RF design.

It’s a supporting actor—quiet, small, and easy to overlook.

Yet it sits exactly where compact modules meet real-world cables, test equipment, and antennas. That makes it disproportionately influential.

Treating this transition as a mechanical and system-level decision—not just a connector choice—prevents many of the “unexplainable” RF issues that surface late in development.

In RF hardware, the smallest interfaces often decide how stable the whole system becomes.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.