MCX Connector Design Rules for RF Hardware

Feb 01,2025

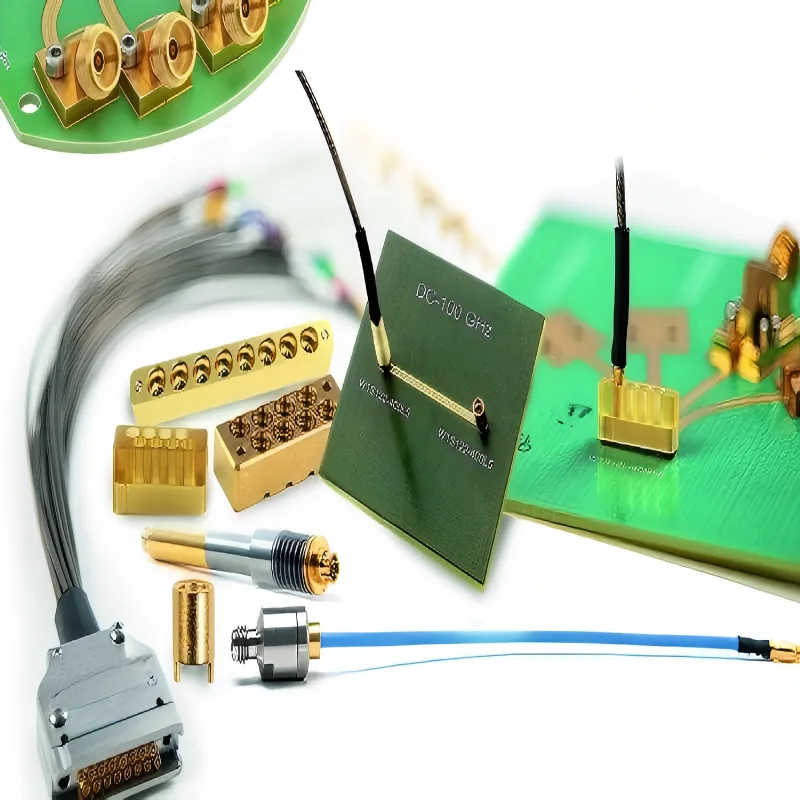

Figure 1 is typically used to visually demonstrate the core problem MCX connectors solve: providing a reliable RF interface in space-constrained designs. The image may show how MCX connectors are integrated at the edge of an RF module with a shield can, or present a size comparison with larger connectors like SMA to highlight its space-saving benefits and accessibility for antenna interfaces during validation. It aims to illustrate that MCX is often chosen not because it is electrically superior, but because it becomes the cleaner option when SMA connectors start forcing compromises elsewhere—such as broken ground pours, awkward antenna routing, or excessive connector height.

In compact RF hardware, connector decisions tend to arrive late. Antennas are debated. RFICs are simulated. Enclosures get revised again and again. The connector usually shows up after the system already “works,” quietly dropped into the schematic because the footprint fits.

That timing is misleading.

The mcx connector is often treated as a smaller SMA or a sturdier MMCX. In reality, it behaves differently—electrically, mechanically, and operationally. It solves real density problems, but it also removes some of the mechanical forgiveness engineers rely on when threaded connectors are used.

This article is not a catalog overview. It’s a set of design rules, written from the perspective of RF hardware that has already gone through layout, integration, and field use. The goal is to help you decide when MCX makes sense, and how to integrate it without quietly degrading link margin, return loss, or long-term reliability.

When should you choose an MCX connector over SMA?

Most engineers don’t replace SMA with MCX because of frequency limits. On paper, both handle sub-6 GHz RF comfortably. The decision usually starts when mechanical constraints begin to dominate the design.

MCX becomes attractive once SMA starts dictating layout instead of adapting to it.

This typically happens in three situations: dense board edges, shallow enclosures, or systems that need fast connect/disconnect without tools.

Compare mcx connector vs SMA vs MMCX size, density, and mating style

From a physical standpoint, MCX sits squarely between SMA and MMCX.

SMA is tall, threaded, and mechanically forgiving. It tolerates torque, side-load, and repeated mating cycles well. That robustness comes at a cost: board edge space, connector height, and assembly time.

MMCX goes to the other extreme. It is compact and fully snap-on, making it popular for ultra-small modules. However, retention force is lower, and long-term reliability becomes sensitive to vibration and cable routing.

MCX splits the difference. The snap-on interface enables quick mating, while the larger geometry improves shielding and retention compared to MMCX. In high-density RF hardware, that balance often matters more than absolute connector size.

This is also where MCX begins to overlap with MMCX design discussions. If you are evaluating that boundary, it is worth comparing against your existing MMCX decisions—for example, as discussed in MMCX connector choice for ultra-compact modules.

Match MCX connector families to GPS modules, cellular modems, and compact RF boards

MCX connectors appear frequently on GPS and GNSS modules, especially where a short coax pigtail exits a shielded RF can. They are also common in compact cellular modems where the antenna interface must remain accessible during validation but cannot dominate the enclosure wall.

A practical pattern shows up repeatedly in field designs: MCX is chosen not because SMA fails electrically, but because SMA forces compromises elsewhere—broken ground pours, awkward antenna routing, or excessive connector height.

Once the connector starts shaping the RF layout instead of serving it, MCX often becomes the cleaner option.

Decide when MCX is better than BNC or SMB in high-density RF hardware

BNC connectors excel in robustness but scale poorly in dense hardware. SMB connectors are compact but are often specified conservatively for systems with frequent reconnects.

MCX sits in the middle ground. It allows multiple RF ports to coexist along a board edge without the spacing penalties of BNC, while offering better mechanical stability than SMB in many snap-on implementations.

In systems that still rely on legacy test or video interfaces, MCX also integrates more cleanly with adapters—something explored later when mcx to bnc adapter paths are discussed.

Map MCX connector options to your RF use cases

One reason MCX causes trouble in production is that it looks deceptively uniform. In reality, impedance family, mounting style, and intended application vary significantly, even when connectors appear interchangeable.

The following selection matrix is designed to be used early—during schematic and layout planning—not after parts have already been ordered.

MCX connector selection matrix / Selection Matrix

| Design Factor | Typical Options |

|---|---|

| Frequency band | DC-3 GHz / 3-6 GHz / video-band 75 Ω |

| Application type | GPS / GNSS module, IoT gateway, test & measurement, CCTV video, automotive, medical |

| Environment | indoor, outdoor, high-vibration, high-temperature |

| Space constraint | tight / normal |

| Required mating cycles | ≤100 / 100-500 / ≥500 |

| Board interface | PCB jack, edge-mount, bulkhead, through-hole |

| Cable type | RG316, RG174, mini-coax, custom |

| Recommendation | Result |

|---|---|

| MCX impedance | 50 ohm or 75 ohm |

| Orientation | straight or right-angle |

| Mounting type | PCB / panel / cable |

| Between-series interface | mcx to sma adapter, mcx to bnc adapter, or none |

| Sealing level | standard, grommet, IP-rated assembly |

Use an MCX connector selection matrix for quick design decisions

Connector decisions often get pushed to layout, but MCX should be locked earlier. Impedance choice alone affects not just the connector, but also cable selection, adapter loss, and test equipment compatibility.

A five-minute review of this matrix during schematic freeze often saves hours of rework later.

Decide between 50 ohm and 75 ohm MCX connector families for RF vs video

Most RF systems use 50 ohm MCX connectors by default. Problems arise when video-oriented 75 ohm variants enter the supply chain unnoticed.

Mixing 50 ohm and 75 ohm MCX components may “work” on the bench, but the mismatch often appears later as degraded return loss or unexplained sensitivity drop. Once adapters or longer cables are added, the issue becomes harder to isolate.

Choose plug vs jack, straight vs right-angle, PCB vs cable-mount in your layout

Straight MCX jacks generally offer cleaner impedance transitions but consume vertical space. Right-angle versions save height while demanding stricter keep-out zones and grounding discipline.

Cable-mount MCX connectors add flexibility and strain relief, while PCB jacks transfer more mechanical stress directly into the board. That trade-off becomes critical in portable or vibration-prone equipment.

Plan MCX cable and adapter paths in compact hardware

Most MCX-related RF issues don’t show up because the connector is “bad.”

They show up because MCX is almost never used alone.

In real hardware, an mcx connector usually sits between two compromises: a dense RF board on one side, and a more forgiving interface—SMA, BNC, or test equipment—on the other. What matters is not the connector itself, but how you get in and out of it.

This is where many otherwise clean RF designs quietly lose margin.

Route mcx cable assemblies to SMA or BNC panels without adding excess loss

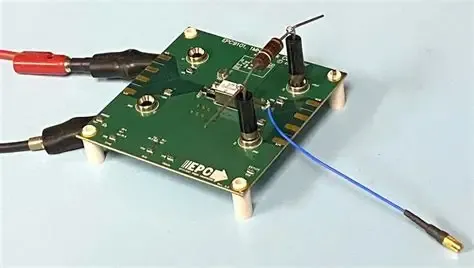

Figure 2 appears in the section discussing how to plan MCX cable and adapter paths in compact hardware. It emphasizes that most MCX-related RF issues don’t show up because the connector is “bad,” but because MCX is almost never used alone. In real hardware, an MCX connector usually sits between two compromises: a dense RF board on one side and a more forgiving interface (SMA, BNC, or test equipment) on the other. What matters is not the connector itself, but how you get in and out of it. The image likely shows that a straight pigtail on the bench behaves very differently once bent around shielding cans, enclosure ribs, or panel hardware. This is where many otherwise clean RF designs quietly lose margin.

Short mcx cable assemblies are often treated as electrically invisible. At low GHz, that assumption is usually fine—until routing reality intervenes.

A straight pigtail on the bench behaves very differently once it’s bent around shielding cans, enclosure ribs, or panel hardware. The cable length might still be “short,” but the bend geometry and grounding environment have changed.

At 2.4 GHz, a well-routed MCX pigtail under roughly 10 cm rarely causes trouble by itself. At 5 GHz, the same cable can become the dominant source of variation if it is forced into tight bends or routed alongside metalwork.

Figure 3 is an extension or specific case of Figure 2, likely focusing on a scenario at a higher frequency like 5 GHz. It is used to concretely illustrate a key point: at 2.4 GHz, a well-routed MCX pigtail under roughly 10 cm rarely causes trouble by itself. At 5 GHz, the same cable can become the dominant source of variation if forced into tight bends or routed alongside metalwork. Designers who work with MCX regularly tend to focus less on theoretical loss numbers and more on where the cable is allowed to breathe. That mindset aligns closely with the routing tradeoffs discussed in detailed MCX cable routing and loss planning.

Use mcx to sma adapter vs mcx to sma cable vs mcx to sma connector in different layouts

This decision looks trivial on a schematic. In practice, it isn’t.

A mcx to sma adapter keeps the signal path short and clean. It also creates a rigid mechanical stack. Any enclosure misalignment or cable pull ends up loading the MCX jack directly.

A mcx to sma cable adds length and loss, but it also absorbs stress. That flexibility matters more than most RF simulations suggest, especially once the product leaves the lab.

A mcx to sma connector transition built into the PCB reduces part count and BOM complexity. It also leaves no room for error. Footprint accuracy, solder fillet quality, and board stiffness suddenly matter a lot more.

In static lab fixtures, adapters often survive just fine. In handheld, vehicle-mounted, or portable equipment, short cables tend to age better—even when they look like the “less elegant” solution.

Integrate mcx to bnc adapter in CCTV receivers and legacy test equipment

Figure 4 appears in the section specifically discussing integrating MCX-to-BNC adapters in CCTV receivers and legacy test equipment. It points out the reality that CCTV receivers and older RF instruments still expect BNC, and that isn’t changing anytime soon. When MCX appears upstream in these systems, the temptation is to bridge the gap with a rigid MCX-to-BNC adapter. Electrically, this usually works. Mechanically, it is risky because BNC cables are heavier and stiffer than most MCX interfaces are designed to tolerate. Over time, that weight translates into side-load on the snap-on joint. Many field-proven designs quietly avoid this by using a short MCX-to-BNC cable instead of a hard adapter. It adds one more part, but it removes a common failure mode.

CCTV receivers and older RF instruments still expect BNC. That reality isn’t changing anytime soon.

When MCX appears upstream in these systems, the temptation is to bridge the gap with a rigid mcx to bnc adapter. Electrically, this usually works. Mechanically, it is risky.

BNC cables are heavier and stiffer than most MCX interfaces are designed to tolerate. Over time, that weight translates into side-load on the snap-on joint, especially if the assembly is bumped or rotated during service.

Many field-proven designs quietly avoid this by using a short MCX-to-BNC cable instead of a hard adapter. It adds one more part, but it removes a common failure mode.

Control pigtail length and bend radius around metalwork and plastic housings

One of the most common MCX failures has nothing to do with impedance.

It happens when a pigtail exits the connector and immediately bends—hard—because the enclosure leaves no room. The system passes RF test. It ships. Months later, retention force drops or intermittent contact appears.

MCX does not like being used as a strain relief.

If the cable must bend immediately, adding a few extra centimeters often improves reliability more than changing connector vendors. This is one of those small, unglamorous adjustments that separates lab-clean designs from hardware that survives real use.

How do MCX connector specs affect RF results?

MCX connectors are small enough that many engineers treat them as electrically neutral. That assumption holds only when the connector family, impedance, and mating conditions line up cleanly.

Once frequencies move past a few gigahertz, small mechanical details start showing up as RF behavior.

Check impedance, frequency range, and VSWR against IEC 61169-36 and CECC 22220

MCX is not a proprietary interface. Its dimensions and electrical targets are defined by international standards.

Referencing IEC 61169-36 or CECC 22220 is less about paperwork and more about alignment. These standards define how MCX fits into the broader coaxial connector family, something that is also summarized—at a high level—in the Wikipedia overview of coaxial connectors.

Designs that ignore these references often rely on catalog tables alone. That works until parts from different suppliers start mating slightly differently, and VSWR begins to drift.

Understand power handling and insertion loss for 50 ohm MCX links up to 6 GHz

MCX connectors are optimized for signal integrity, not power delivery.

Insertion loss per interface is small enough to ignore—once. When MCX connectors are cascaded with adapters and panel transitions, the cumulative effect becomes measurable, especially near the upper end of their frequency range.

This is where MCX-to-SMA transitions deserve more scrutiny than they usually get. Even though SMA is the “stronger” connector, the MCX side often sets the real limit.

Handle 75 ohm MCX connectors in high-density video and receiver front-ends

75 ohm MCX connectors behave predictably in video systems that are designed around them. Problems arise when those parts drift into RF signal paths unintentionally.

In mixed RF/video hardware, it is surprisingly easy for 50 ohm and 75 ohm MCX parts to coexist on the same BOM. The mismatch rarely causes immediate failure. Instead, it shows up later as degraded return loss or inconsistent receiver sensitivity.

Once longer cables or adapters enter the path, isolating the root cause becomes difficult. The safest approach is to treat impedance selection as a first-order design decision, not a late-stage detail.

Control mechanical stress and retention on MCX jacks

Electrically, MCX behaves predictably.

Mechanically, it behaves honestly.

The snap-on interface does not hide abuse. If side-loads, vibration, or cable weight are present, the connector will show it—sometimes slowly, sometimes all at once.

Design PCB footprints and keep-out zones for snap-on MCX connectors

Most MCX footprint problems don’t come from bad drawings. They come from copied assumptions.

Designers reuse a reference footprint, shrink the keep-out area, and trust solder joints to do mechanical work they were never meant to do. That works until the first cable is pulled at an angle.

Good MCX layouts leave breathing room. Copper is cleared where the outer shell can flex. Ground stitching is placed deliberately, not densely. The goal isn’t maximum copper—it’s controlled compliance.

This kind of connector-aware layout thinking is consistent with broader RF connector planning practices outlined in a comprehensive RF connector selection guide for cables and antennas.

Limit side-loads and torque on MCX jacks in vibration-prone systems

Threaded connectors tolerate torque. MCX does not.

In vibration-prone systems—vehicles, portable instruments, industrial enclosures—the worst stress often comes from cable motion, not connector insertion. Even modest cable mass can translate into repeated micro-loads on the snap-on joint.

Designers who have seen MCX failures in the field tend to stop asking, “Is the connector rated for this?” and start asking, “Where does the force go?”

If the answer is “into the PCB,” the design is usually fragile.

Add strain relief and tie-downs for mcx cable assemblies in handheld and mobile gear

Strain relief is not optional with MCX. It is the difference between a connector that lasts a year and one that lasts a product lifetime.

A simple tie-down, adhesive anchor, or molded relief often reduces stress more effectively than switching connector vendors. It’s unglamorous, but it works.

This is especially true when mcx cable assemblies are used in handheld or wearable devices, where cables are touched, twisted, and repositioned constantly.

Audit MCX connector reliability in harsh environments

Qualify MCX connector durability, mating cycles, and gold plating thickness

Not all MCX connectors age the same way.

Gold plating thickness, contact spring geometry, and shell material all influence how retention force changes over time. Thin plating wears quickly when connectors are re-mated during test and service.

If your design expects more than occasional mating, plating thickness should be a specification—not an assumption.

Evaluate temperature, moisture, and vibration performance for automotive and aerospace use

Temperature cycling exposes MCX weaknesses earlier than vibration testing. Expansion mismatch between connector, solder, and PCB quietly changes contact pressure.

In automotive and aerospace contexts, MCX is usually acceptable only when supported by proper strain relief, controlled cable routing, and conservative mating-cycle assumptions.

Qualification here is less about pushing limits and more about avoiding surprises.

Build incoming inspection checklists for MCX connector and cable assembly suppliers

Incoming inspection catches problems before they propagate.

Common issues include inconsistent center-pin depth, uneven crimping, and loose shells. None of these show up in a quick continuity check. All of them show up later as intermittent RF behavior.

Teams that rely on MCX heavily often develop simple mechanical inspection steps—not because the connector is unreliable, but because snap-on interfaces expose variation more clearly.

Review recent MCX connector trends in RF and wireless modules

Put MCX connectors in context of the growing RF connector market

As RF hardware continues to shrink, connector selection becomes less about tradition and more about fit. MCX occupies a space that neither SMA nor MMCX fills cleanly: compact, shielded, and fast to mate.

Its continued use in wireless modules reflects that balance rather than raw performance leadership.

For general background on how MCX fits into standardized RF interfaces, the overview of coaxial connectors provides useful historical context without diving into vendor specifics.

Learn from new MCX cable assemblies for wireless communication modules

Recent MCX cable assemblies focus less on novelty and more on consistency: tighter impedance control, improved strain relief, and better tolerance stacking.

These changes are incremental, but they reflect lessons learned from field failures rather than lab measurements.

Watch emerging requirements: non-magnetic materials, PFAS-free plating, and higher-frequency variants

Resolve common MCX connector selection questions

Can I mix 50 ohm and 75 ohm MCX connectors or cables in the same signal path?

You can, electrically. You usually shouldn’t.

The mismatch often hides during early testing and shows up later as degraded return loss or sensitivity drift, especially once adapters or longer cables are added.

When is an mcx to sma adapter better than routing a longer mcx to sma cable?

How short should an mcx cable be kept at 2.4 GHz or 5 GHz to avoid excessive loss?

What PCB layout mistakes most often cause poor MCX connector return loss?

How do I qualify an MCX connector supplier for automotive or aerospace projects?

Does the snap-on MCX interface loosen over time, and how can I test retention force?

Which standards should I reference when specifying MCX connectors?

Final perspective

The mcx connector is not a compromise connector. It is a context-dependent one.

When MCX is chosen deliberately—matched to the right impedance family, supported mechanically, and integrated with realistic cable routing—it solves density and accessibility problems cleanly. When it is treated like a smaller SMA, it exposes every shortcut.

That difference is not theoretical. It shows up in layouts, in field returns, and eventually in whether a design quietly holds margin—or slowly bleeds it away.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.