RF Connector Guide for Cables, Antennas and Test Systems

Jan 27,2025

Preface

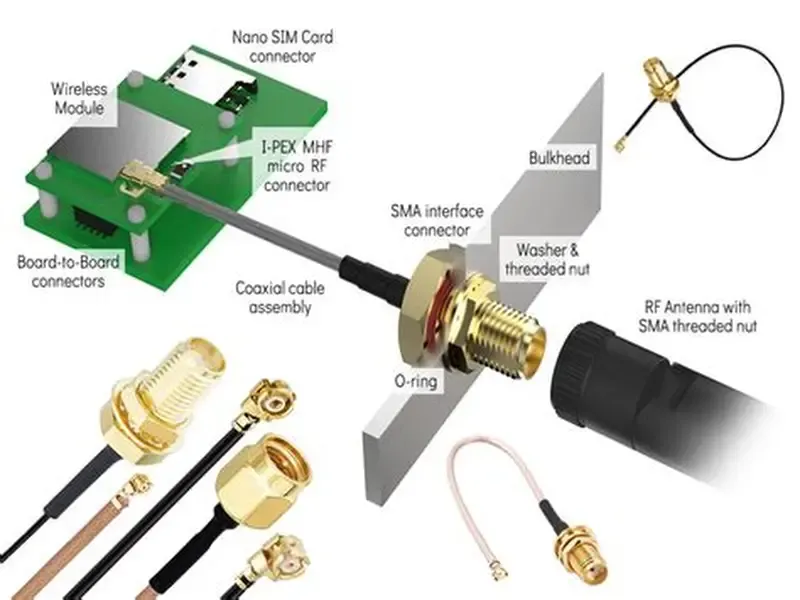

Figure 1 aims to set the tone for the entire guide, explaining that issues in RF systems (such as reduced range or measurement drift) are often not sudden hard failures but slow performance degradation, with connectors frequently being the root cause as they sit at the boundary between ideal RF theory and messy physical reality.

Most RF systems don’t break in obvious ways. They don’t fail during bring-up. They don’t fail during basic testing. In many cases, they don’t even fail during early deployment. What happens instead is slower and harder to pin down: range shrinks, measurements drift, or a link that used to feel “solid” becomes sensitive to handling.

When teams go back to investigate, the RF connector is rarely the first suspect.

That makes sense. An RF connector usually enters the design late. By the time it appears, the radio already works and the antenna choice feels settled. The connector’s job seems mechanical—just a way to attach a cable. Unfortunately, that assumption ignores where connectors actually live: at the boundary between ideal RF theory and messy physical reality.

This guide is written from that boundary. It doesn’t try to catalog every connector type. Instead, it focuses on how connector choices influence reliability, layout, and long-term behavior in real RF systems, especially once those systems leave the lab.

Why do RF connectors quietly decide system reliability?

See how RF connectors sit between radios, cables and antennas

Figure 2 emphasizes that even in small systems, connectors are the most mechanically active part of the RF path, experiencing vibration, assembly handling, and routing stress. Subtle changes in connector behavior when the system state changes (e.g., enclosure closed, unit transported) can lead to non-repeatable RF performance.

In schematics, RF connectors are usually abstracted away. They might be shown as a generic port, or not shown at all. In hardware, they sit at every place where movement is possible. Radio to cable. Cable to panel. Panel to antenna. Each of those transitions depends on a connector maintaining geometry and contact pressure while the rest of the system shifts around it.

This matters even in small systems. A short SMA cable inside a compact enclosure still sees vibration from fans, handling during assembly, and stress from tight routing. A BNC cable on a test bench might be reconnected dozens of times a week. In both cases, the connector becomes the most mechanically active part of the RF path.

Engineers often notice this only after something changes. Measurements that looked stable on the bench start to move once the enclosure is closed or the unit is transported. Nothing “electrical” was changed, yet RF behavior is no longer repeatable. In many of those cases, the connector is where the system quietly crossed a threshold.

Recognize the failure modes that rarely appear on schematics

Connector-related problems almost never look like clean failures. Radios keep transmitting. Antennas still radiate. What changes is margin. A coupling nut loosens slightly. Contact plating wears unevenly. The cable shield near the connector fatigues where it flexes the most.

Temperature makes this worse over time. Different materials expand and contract at different rates, and that motion slowly alters contact conditions. Add moisture or contamination, and the process accelerates. None of this appears in RF simulation tools, and very little of it shows up during initial validation.

That’s why connector issues are so often misdiagnosed. Teams may suspect antenna tuning, firmware timing, or even silicon variation before considering that the RF connector itself is no longer behaving the way it did on day one.

Connect this RF connector guide to your cable knowledge

Most RF engineers already understand coaxial cables well enough. Attenuation versus frequency, shielding effectiveness, and basic mechanical limits are familiar concepts. Cables like RG316 coaxial cable are chosen because they fit tight spaces and tolerate heat, not because they are exotic or particularly low loss.

In practice, RG316 is rarely the problem. What causes trouble is how it is terminated and supported. A good cable can still perform poorly if the connector introduces an impedance step, weak strain relief, or long-term mechanical instability. Many “cable problems” turn out to be connector problems once the system is inspected closely.

This guide focuses on that interface layer—the part that tends to be assumed correct once the cable type is selected.

How should you classify RF connectors without getting lost in part numbers?

Group RF connectors by impedance and frequency first

If connector selection feels overwhelming, it’s usually because the process starts too deep. Part numbers come first, and fundamentals come later. A more reliable approach is to step back and classify by impedance and frequency range.

Most RF communication systems operate at 50 ohms. Video and broadcast systems are typically built around 75 ohms. That single distinction already removes many incorrect options. Mechanical compatibility does not imply electrical compatibility, and mixing impedances introduces discontinuities that become more harmful as frequency increases.

Frequency limits themselves deserve skepticism. A connector may be rated for a given frequency, yet still degrade return loss enough to matter well before that limit is reached. These effects don’t cause immediate failure; they quietly consume margin.

Then separate by size: from N and BNC down to MCX and MMCX

Once impedance and frequency are fixed, connector size becomes the real trade-off. Larger connectors such as N-type and BNC are mechanically forgiving. They tolerate handling, vibration, and repeated reconnection with relatively little drama.

Smaller connectors—SMA, MCX connector, and MMCX connector—make compact layouts possible, but they demand better mechanical discipline. Side loads matter more. Bend radius matters more. Strain relief stops being optional. Designs that ignore this often work initially and then drift after assembly or deployment.

Choosing a miniature connector is not just about saving space. It is a commitment to tighter mechanical control.

Finally map connector families to real applications

Connector families become easier to reason about when viewed through how they are actually used. BNC connectors remain common in video systems, CCTV installations, and laboratories because they are quick to connect and tolerant of frequent use. SMA connectors dominate RF communication and antenna interfaces where frequency and enclosure size matter more. MCX and MMCX connectors are most often found inside compact modules where routing flexibility is critical.

Seen this way, connector selection stops being abstract. The question is no longer “Which connector is best?” but “Which connector fails least often in this environment?”

How do you choose between SMA, BNC and N-type RF connectors for your project?

Use SMA connector when space and frequency both matter

Figure 3 appears in the section discussing how to choose between SMA, BNC, or N-type connectors for a project. It illustrates that the SMA connector sits in a practical middle ground but also points out its sensitivity: poor tolerance to inadequate torque control or repeated abuse. In dense layouts, connector behavior (not cable attenuation) can become the dominant variable.

The SMA connector sits in a practical middle ground. It supports high frequencies, fits into small enclosures, and pairs naturally with thin coaxial assemblies. That balance explains why it appears in so many modern RF designs.

The downside is sensitivity. SMA connectors do not tolerate poor torque control or repeated abuse. In dense layouts, engineers often discover that connector behavior—not cable attenuation—becomes the dominant variable. This pattern tends to show up only after systems are handled in the field, a point that comes up repeatedly when teams revisit earlier design assumptions similar to those discussed in SMA Connector Selection for RF Cables and Antennas.

Keep BNC cable for video, CCTV and lab instruments

Figure 4 is presented alongside Figure 3 to contrast and explain the advantageous domain of BNC connectors. It emphasizes that for moderate frequencies, BNC cable assemblies deliver stable performance with less maintenance effort, explaining why they remain common on test benches even as smaller connectors dominate inside products.

BNC connectors persist because they solve everyday problems efficiently. Their bayonet lock makes partial engagement unlikely, and they tolerate frequent reconnection better than most threaded interfaces. In labs and video systems, that reliability often matters more than compact size.

For moderate frequencies, BNC cable assemblies deliver stable performance with less maintenance effort. That is why they remain common on test benches even as smaller connectors dominate inside products.

Reserve N-type connectors for higher power and outdoor feedlines

N-type connectors are chosen less often, but usually for good reasons. They handle power, vibration, and environmental exposure better than smaller connectors. Outdoor antenna systems and long feedlines benefit from this robustness.

A common pattern is to route RF internally with SMA and transition to N-type at the enclosure boundary. It is not elegant, but it tends to age well.

How can you pair RF connectors with RG316 and other coaxial cables correctly?

Match connector families to RG316, RG58, RG142 and mini-coax

Figure 5 appears in the section discussing how to correctly pair RF connectors with coaxial cables like RG316. It serves as a concrete example that pairing is not just about “what fits” but about predictable behavior once the system is assembled, routed, and left alone for the long term. The text notes that SMA connectors, especially panel-mounted ones, tend to create a stiff transition point, and if the cable is forced to bend immediately after the connector, fatigue accumulates quickly.

Figure 6 is another pairing example following Figure 5, used to compare the differences when different connectors are paired with the same cable (RG316). It emphasizes that MCX connectors rely on snap-on retention rather than threaded engagement, making them faster to assemble and easier to integrate into dense layouts, but also more sensitive to lateral forces. MCX connectors work well when cable routing is controlled and movement is limited.

Figure 7 is the third and final connector-cable pairing example. It illustrates that the MMCX with RG316 combination is attractive for space minimization. The risk is mechanical, not electrical: MMCX connectors tolerate rotation but do not tolerate repeated bending close to the interface. Successful MMCX designs usually fix the cable early, close to the connector, and avoid using MMCX as a user-accessible connector for frequent reconnection.

In practice, pairing an RF connector with a coaxial cable is rarely about “what fits.” It is about what behaves predictably once the system is assembled, routed, and left alone for months or years. This is where many designs quietly go wrong.

Take RG316 coaxial cable as an example. It is popular because it is thin, flexible, and tolerant of high temperatures. Engineers use it inside compact enclosures, between RF modules and panel connectors, or as short jumpers to antennas. Electrically, it behaves well into the gigahertz range. Mechanically, however, it is unforgiving near the connector.

SMA, MCX, and MMCX connectors are all commonly used with RG316, but they do not stress the cable in the same way. SMA connectors, especially panel-mounted ones, tend to create a stiff transition point. If the cable is forced to bend immediately after the connector, fatigue accumulates quickly. MCX and MMCX connectors reduce bulk, but they also reduce mechanical margin. Side loading that would be harmless on a BNC can permanently damage a miniature interface.

Larger cables such as RG58 or RG142 shift the balance. Their stiffness provides some inherent strain relief, which is why they pair more comfortably with BNC or N-type connectors. The cable itself absorbs part of the mechanical stress, instead of passing it directly into the connector interface.

This difference is often overlooked because it does not show up in electrical specifications. It only becomes obvious after a system has been assembled, disassembled, and handled a few times.

Avoid “almost fits” crimps and solder joint

One of the most common RF assembly mistakes is the “almost fits” connector. The ferrule crimps. The center conductor solders. The cable looks secure. On the bench, the link works. That is usually where the validation stops.

The problem is not immediate continuity; it is geometry. When a connector is designed for a slightly different cable diameter or dielectric structure, the impedance transition happens inside the connector body. At low frequencies, this may be tolerable. At higher frequencies, it becomes a repeatable source of reflection.

This is especially risky with RG316. Because the cable is small, it is tempting to adapt connectors meant for similar mini-coax types. The mechanical mismatch may be subtle, but RF systems are sensitive to subtle things. Once the connector heats, cools, and flexes a few dozen times, the weak point announces itself.

If you ever see a design where performance depends on how the cable is “held just right,” the connector–cable interface is usually the first place to look.

Use a quick RF connector + cable loss check before freezing the design

Most teams already estimate cable loss. Fewer teams explicitly account for connector loss in a structured way. Individually, connector losses are small. Collectively, they can consume more margin than expected.

A simple check before design freeze often prevents late surprises.

RF Connector and Coax Link Budget Quick Sheet

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Connector family | SMA / BNC / N / MCX / MMCX |

| Typical loss per connector pair (dB) | Representative insertion loss at operating frequency |

| Number of connector pairs | Total mated interfaces in the link |

| Cable type | RG316 / RG58 / RG142 |

| Cable length (m) | Physical length of the coax |

| Cable attenuation (dB/m) | At operating frequency |

| Operating frequency (GHz) | System frequency |

| Total connector loss (dB) | Sum of connector losses |

| Total cable loss (dB) | Cable attenuation × length |

| Total link loss (dB) | Connector loss + cable loss |

| Transmit power (dBm) | Available TX power |

| Required margin (dB) | Design margin |

| Resulting margin (dB) | Remaining link margin |

Core relationships:

- Total connector loss = loss per connector pair × number of pairs

- Total cable loss = attenuation per meter × cable length

- Total link loss = connector loss + cable loss

- Remaining margin = TX power − total link loss − required margin

For short internal links using RG316, connector loss can easily dominate cable loss. This surprises teams who assume “short cable means negligible loss.” It is not wrong, but it is incomplete.

How do miniature RF connectors like MCX and MMCX change your layout?

Where MCX connector makes sense compared to SMA

The MCX connector often appears in designs that are trying to shrink without fully committing to ultra-miniature interfaces. Compared to SMA, it saves space and reduces weight, but it also changes how mechanical stress is handled.

MCX connectors rely on snap-on retention rather than threaded engagement. This makes them faster to assemble and easier to integrate into dense layouts. It also means they are more sensitive to lateral forces. A cable that would simply rotate on an SMA may partially disengage an MCX if strain relief is poor.

This is not a flaw; it is a trade-off. MCX connectors work well when cable routing is controlled and movement is limited. They are less forgiving when cables are free to move.

The underlying mechanical behavior aligns with how coaxial interfaces are described in general RF connector overviews, such as those summarized in the RF connector classification reference, where retention method is as important as electrical rating.

When MMCX connector plus RG316 wins in compact modules

MMCX connector paired with RG316 shows up frequently in GNSS receivers, IoT gateways, and embedded radio modules. The combination is attractive because it minimizes space while maintaining acceptable RF performance.

The risk is not electrical; it is mechanical. MMCX connectors tolerate rotation, but they do not tolerate repeated bending close to the interface. In compact modules, there is often very little room to introduce a gentle bend radius or a proper anchor point.

Designs that succeed with MMCX usually do two things consistently. First, they fix the cable early, close to the connector, so movement is transferred into the cable rather than the interface. Second, they avoid using MMCX as a user-accessible connector. Once frequent manual reconnection enters the picture, failure rates climb quickly.

This pattern is well understood in high-frequency connector practice and aligns with how precision interfaces like SMA are characterized in formal definitions, such as those found in the SMA connector reference maintained by standards bodies and summarized publicly.

Manage strain relief and rerouting for pigtails and jumpers

Miniature RF connectors change how layouts are judged. With larger connectors, routing errors may cost a bit of margin. With MCX or MMCX, routing errors can cost reliability.

Strain relief does not need to be elaborate. A simple clamp, adhesive anchor, or cable guide often makes the difference between a stable interface and one that degrades over time. What matters is preventing the connector from seeing repeated bending or side loading.

In compact designs, it is tempting to let pigtails “float.” That usually works on the bench. It works less well once the enclosure is closed and the system is moved. Engineers who have had to rework RF modules in the field tend to become very conservative about this detail.

How should you connect RF connectors to antennas, enclosures and lab panels?

Plan bulkhead and panel RF connectors for outdoor antennas

Panel and bulkhead RF connectors are often treated as mechanical details. Hole size, nut type, and maybe an O-ring—job done. In reality, this interface decides whether an outdoor RF path stays stable after months of temperature swings, vibration, and weather exposure.

Thread length and panel thickness matter more than most teams expect. A connector that barely engages the nut may pass initial testing but loosen over time. An O-ring that is over-compressed or under-compressed becomes ineffective quickly. In outdoor antenna systems, especially those mounted on metal enclosures, grounding continuity through the panel is just as important as RF continuity.

It is also common to see internal cables routed too tightly right after a bulkhead connector. This creates a rigid stress point exactly where mechanical stability is most critical. Designs that last tend to leave a small service loop inside the enclosure, even when space is limited. That loop absorbs movement that would otherwise be transferred into the connector body.

Route SMA cable and BNC cable inside enclosures without killing margin

Inside an enclosure, RF routing decisions are often made late, after power, digital, and mechanical constraints are already fixed. The result is usually “whatever fits.” Electrically, that may be acceptable. Mechanically, it often is not.

An SMA coax cable routed tightly along a metal edge or pressed against a stiff harness will behave differently over time than it did on the bench. Small changes in cable position can alter stress at the connector, which in turn affects contact stability. The same applies to BNC cable assemblies in larger enclosures, where weight and leverage become factors during transport or vibration.

Teams that have fewer field issues tend to follow a simple rule: RF cables should be the last thing to move when the enclosure is shaken. If the RF cable moves first, the connector will eventually pay the price.

Keep lab RF panels serviceable for repeated reconnection

Laboratory RF panels live a very different life from deployed hardware. They see frequent reconnection, adapter stacking, and occasional misuse. Designing them like production hardware usually leads to early wear.

Serviceable lab panels leave generous spacing between connectors, clearly label signal paths, and accept that connectors are consumables. Replaceable front-panel connectors are far cheaper than replacing an entire instrument front end. Torque control also matters more than many labs realize. Precision connectors are not designed for “finger-tight plus a twist.”

These practices align closely with how RF test interfaces are treated in metrology environments, where connector repeatability is considered part of measurement uncertainty rather than an afterthought.

What reliability, ESD and environmental checks should RF connectors pass?

Validate mating cycles, torque and VSWR drift over time

Every RF connector has a finite mating life. That number is usually in the hundreds, not the thousands. Exceed it, and contact geometry starts to change in subtle ways. Return loss degrades. Measurements drift. At that point, tightening harder rarely helps.

Tracking VSWR over time is one of the simplest ways to catch connector degradation early. A connector that shows a slow but consistent change across repeated measurements is telling you something mechanical is happening. Ignoring that signal often leads to much harder troubleshooting later.

Combine RF connectors with proper ESD and surge paths

RF connectors are often the first metal part a user touches. That makes them natural entry points for ESD events. Without a defined discharge path, that energy can couple directly into sensitive RF front ends.

Good designs give ESD a place to go before it reaches anything expensive. This usually means controlled grounding at the connector interface and a clear separation between mechanical grounding and RF signal paths. Standards bodies describe these interactions in general terms, such as those outlined in IEC electrostatic discharge guidance summarized in public references like the IEC 61000-4-2 overview, but the exact implementation is always system-specific.

Ignoring this aspect rarely causes immediate failure. Instead, it shortens component life quietly.

Qualify RF connectors for temperature, vibration and moisture

Environmental qualification is where RF connectors often fail last—and most expensively. A connector that performs perfectly in a controlled lab may degrade quickly under vibration, humidity, or thermal cycling.

Outdoor, automotive, and industrial systems expose connectors to combined stresses. Temperature changes alter contact pressure. Vibration introduces micro-motion. Moisture accelerates corrosion. Individually, these effects are manageable. Together, they are unforgiving.

Designs that survive these environments usually rely on conservative connector choices, generous mechanical support, and validation that extends beyond initial electrical performance.

How is the RF connector market evolving with 5G, IoT and satellite links?

Track demand growth for RF connectors in new infrastructure

The growth of 5G, fixed wireless access, and low-Earth-orbit satellite systems has increased the number of RF interfaces in deployed hardware. More radios mean more connectors, and more connectors mean more potential failure points.

This has shifted attention away from peak performance and toward repeatability and long-term stability. In many infrastructure projects, connector quality now affects maintenance cost more than initial RF specifications.

Watch the shift toward higher-frequency and smaller-form-factor connectors

As operating frequencies rise, tolerance for imperfection shrinks. Small impedance steps and mechanical inconsistencies that were acceptable at lower frequencies become dominant sources of loss and reflection.

At the same time, form factors continue to shrink. This combination leaves less margin for poor connector choices. Miniature connectors are being pushed into roles once filled by larger interfaces, which makes mechanical discipline more important than ever.

Learn from field failures and connector quality issues in recent projects

Many RF connector problems are not design errors but quality and consistency issues. A small plating variation across a production batch can translate into measurable RF variation across systems. These issues often surface only after deployment, when replacing connectors becomes expensive.

Teams that close this loop—by feeding field failure data back into connector selection and validation—tend to see steady improvements in long-term reliability. Those that do not often repeat the same mistakes in slightly different forms.

Closing Thoughts

RF connectors rarely attract attention when things go well. They become visible only when something starts to drift. Treating them as first-class elements of the RF system—rather than as afterthoughts—does not eliminate problems, but it makes them predictable.

Predictable problems are easier to design around. In RF systems, that is often the difference between a product that merely works and one that keeps working.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.