SMA Connector Selection for RF Cables and Antennas

Jan 26,2025

Why does the SMA connector matter more than it looks?

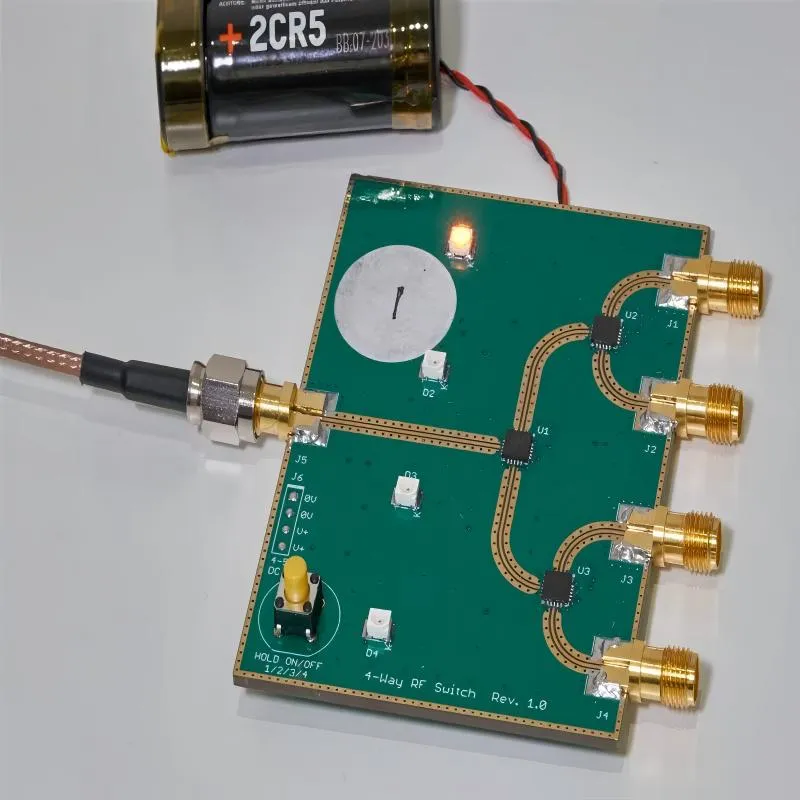

Figure 1 sets the context for discussion, emphasizing that while SMA connectors are familiar and inexpensive, their critical role as a 50-ohm transition point is often overlooked, leading to issues surfacing late in development.

In most RF designs, the SMA connector is treated as solved hardware. It is familiar, inexpensive, and already sitting on the shelf. Engineers rarely debate it the way they debate antennas, RF chipsets, or matching networks. By the time an SMA interface shows up in the design, the radio already works and the enclosure shape is more or less fixed.

That timing is misleading.

An SMA connector is not just a mechanical fastener. It is a defined 50-ohm transition that sits exactly at the point where the RF environment changes. On one side, you have a controlled trace or a known coax geometry. On the other, you have a different cable, a panel feed-through, or free space via an antenna. The connector is where assumptions about impedance continuity either hold—or quietly stop holding.

This is why SMA issues tend to surface late. Early testing looks fine. Sensitivity numbers pass. Link budget calculations seem conservative enough. Then something small changes: a jumper is replaced, a bulkhead is added, or the product is installed in a different orientation. Suddenly, margin feels thinner than expected. Nothing is obviously broken, but the system is less forgiving.

In real hardware, SMA connectors sit at boundaries that engineers do not like to revisit. External antennas on routers and gateways pass through SMA bulkheads. Compact RF modules rely on short SMA coax cable jumpers to reach host boards. Test fixtures use SMA ports that are connected and disconnected hundreds of times. Each of these locations concentrates mechanical wear and electrical discontinuity into a very small volume.

This guide treats the SMA connector as part of the RF system, not as neutral plumbing. If you already understand SMA cable loss or how SMA antenna cable length affects range, the missing piece is often the interface itself rather than the cable or the antenna.

See how a small RF connector can cap or unlock link margin

Figure 2 appears in the section explaining SMA connector specifications, emphasizing that what matters in practice is not the frequency number on the datasheet, but the connector’s ability to maintain its geometry consistently over time, as small changes accumulate and erode link margin.

From a specification point of view, the SMA is a threaded RF connector built around a 50-ohm coaxial geometry. Standard SMA connectors are commonly rated to 18 GHz, while higher-precision versions extend usable performance to 26.5 GHz. That easily covers Wi-Fi, LTE, sub-6 GHz 5G, GPS, and most laboratory measurements.

What matters in practice is not the frequency number on the datasheet. It is how consistently the connector maintains that geometry over time. Small changes—center pin wear, dielectric deformation, surface contamination—show up as incremental increases in reflection. No single change looks dramatic. Combined, they eat into link margin.

Engineers often encounter this during late validation. Swapping one SMA jumper for another changes readings more than expected. Rotating the connector slightly affects noise floor. These behaviors point to an interface that is no longer behaving like the ideal 50-ohm transition assumed during design.

Recognize where SMA connectors quietly sit in real designs

Figure 3 illustrates the ubiquity of SMA connectors in RF systems that value predictability, and points out that because they are used everywhere, teams often mistakenly assume all SMA connectors behave the same, while differences in materials, plating quality, and mechanical tolerances become visible in systems experiencing vibration or frequent reconnection.

SMA connectors appear in RF systems that value predictability. Wi-Fi routers and LTE or 5G CPEs use SMA bulkheads for external antennas because the interface is compact and robust. RF modules use SMA jumpers because the threaded connection survives handling better than snap-on alternatives. GPS receivers rely on SMA antenna feeds because timing stability depends on consistent RF paths. Test panels use SMA because it balances frequency capability with size.

Because SMA is used everywhere, teams often assume that all SMA connectors behave the same way. Over time, differences in materials, plating quality, and mechanical tolerances become visible—especially in systems that see vibration or frequent reconnection. These differences rarely appear in first-article testing, which is why they tend to surprise teams later in the product cycle.

Connect this guide with your existing SMA cable knowledge

If you have already worked through SMA antenna cable length and loss or practical SMA RF cable assemblies, you have seen how cable selection affects attenuation and routing flexibility. This guide does not revisit those topics directly. Instead, it focuses on the interface that both sides of the cable depend on.

Cable loss calculations usually treat connector loss as a fixed, small number. That assumption holds only when SMA interfaces are properly matched, correctly torqued, and not overloaded with adapters. The cable-side view of this interaction is discussed in resources such as SMA RF cable length, loss planning, and practical design. This article approaches the same RF path from the connector inward.

How should you interpret SMA connector specs (impedance, frequency, materials)?

Read the basics: 50 Ω, passband, and VSWR limits

All standard SMA connectors are designed around a 50-ohm impedance. This distinguishes them from visually similar 75-ohm connectors used in video systems. Electrically, SMA does not have a sharp cutoff frequency. Performance degrades gradually as geometry imperfections and higher-order modes become more significant.

Most commercial SMA connectors are specified to 18 GHz. Precision SMA variants extend that limit to 26.5 GHz by tightening tolerances on the center conductor and dielectric support. Even when operating well below those frequencies, higher-grade SMA connectors tend to maintain more stable return loss across temperature changes and repeated mating.

VSWR is rarely guaranteed as a single number for connectors alone, but in real systems, a clean and properly torqued SMA pair typically maintains return loss better than 20 dB across much of its rated band.

Understand material choices: brass vs stainless vs plating

Figure 4 appears in the section discussing material selection, illustrating that brass SMA connectors are widely used because they machine accurately, hold threads well, offer good conductivity at reasonable cost, and maintain stable contact resistance and corrosion resistance over many mating cycles when gold-plated.

Figure 5 is presented alongside Figure 4 to contrast and explain that stainless-steel SMA connectors prioritize durability, tolerate higher torque, and survive harsh environments better, making them suitable for outdoor enclosures and vibration-heavy installations, though the electrical penalty becomes more noticeable as frequency increases.

Material selection is where electrical and mechanical considerations collide. Brass SMA connectors dominate commercial RF products because brass machines accurately, holds threads well, and offers good conductivity at reasonable cost. When gold-plated, brass SMA connectors maintain stable contact resistance and resist corrosion over many mating cycles.

Stainless-steel SMA connectors prioritize durability. They tolerate higher torque and survive harsh environments better, which makes them suitable for outdoor enclosures and vibration-heavy installations. The electrical penalty is usually small at lower frequencies but becomes more noticeable as frequency increases.

Plating choice affects long-term behavior more than many teams expect. Gold plating minimizes oxidation and stabilizes contact resistance. Nickel plating improves wear resistance but can increase micro-contact resistance over time. Mixing connector grades within a single RF path—such as pairing a low-cost jumper with a high-grade panel connector—often accelerates wear on the softer component.

Use torque and mating-cycle ratings as real design inputs

SMA connectors are commonly rated for around 500 mating cycles when used within their recommended torque range. That rating assumes clean threads, proper alignment, and controlled tightening. In practice, especially in lab environments, those conditions are not always met.

For typical brass SMA connectors, recommended torque usually falls between 0.3 and 0.6 N·m. Stainless-steel variants often allow higher values. Under-torque permits micro-movement that leads to fretting and rising contact resistance. Over-torque risks thread damage or deformation of the dielectric support.

This is why experienced RF engineers treat torque as a specification rather than a suggestion. Consistent torque preserves electrical repeatability and extends connector life, particularly in systems where SMA interfaces are connected and disconnected frequently.

How do you pair SMA connectors with RG316 and other RG cables in practice?

In theory, pairing an SMA connector with a coaxial cable is straightforward. Both are nominally 50 ohms. Both have been used together for decades. Datasheets list compatible cable types, and assembly instructions are widely available. In practice, this pairing is where many RF links quietly lose margin.

The reason is simple. Cable selection is usually driven by routing, temperature rating, or availability. Connector selection is often driven by habit. When those two decisions are made independently, the interface between them becomes the weakest point in the RF path.

Match SMA connector variants to RG316, RG58, RG142, and mini cables

Different RG cables place very different mechanical and electrical demands on an SMA termination. RG316 coaxial cable, for example, uses a PTFE dielectric and silver-plated conductors. It is thin, flexible, and tolerant of higher temperatures, which makes it popular inside enclosures and near heat sources. SMA connectors intended for RG316 are designed around that geometry: the dielectric support length, center-pin engagement, and crimp ferrule dimensions are all tuned to maintain impedance continuity.

RG58 tells a different story. Its larger diameter and polyethylene dielectric require a different SMA connector structure. RG142 sits somewhere in between, offering lower loss than RG316 but at the cost of stiffness. Treating these cables as interchangeable at the connector level often works mechanically, but electrically it introduces small impedance steps right at the transition.

Those steps rarely show up as dramatic return-loss spikes. Instead, they appear as slightly higher insertion loss or sensitivity to cable movement. Over short distances, the effect may be negligible. Over multiple SMA pairs or at higher frequencies, it accumulates.

This is one reason why experienced teams tend to standardize SMA connector variants alongside cable families, rather than mixing and matching based on what “almost fits.”

Avoid impedance and size mismatches at the cable–connector interface

Figure 6 emphasizes the risk of impedance and size mismatches at the cable-connector interface. Such mismatches rarely show up as dramatic return-loss spikes, but instead appear as slightly higher insertion loss or sensitivity to cable movement, effects that accumulate over multiple SMA pairs or at higher frequencies.

One of the most common failure modes at the SMA–cable interface is not a broken joint, but a mismatched geometry. A connector designed for one cable diameter can often be forced onto another. The crimp looks acceptable. Continuity checks pass. RF performance, however, is no longer predictable.

This is especially risky when 75-ohm coax is involved. Visually, some 75-ohm cables resemble RG58 or RG316 closely enough to tempt substitution. Electrically, forcing a 75-ohm structure into a 50-ohm SMA connector creates a localized impedance discontinuity that reflections cannot ignore. The system may still function, but margin becomes fragile.

If you need background context on why SMA geometry is defined the way it is, the overview in SMA connector interface definition explains the mechanical and electrical constraints that shape the standard. Likewise, broader comparisons across connector families are summarized in list of RF connector types, which helps explain why SMA behaves differently from BNC, N, or snap-on interfaces.

Use a quick SMA + cable loss and power budget sheet before release

Rather than relying on intuition, many RF teams run a simple loss and margin check before freezing a design. The goal is not to predict performance to the third decimal place, but to catch combinations that are already too close to the edge.

Below is a compact worksheet that treats SMA connector loss as a variable rather than an afterthought.

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Frequency_GHz | Operating frequency |

| Cable_type | RG316 / RG58 / RG142 |

| Cable_length_m | Total cable length |

| Cable_attenuation_dB_per_m | Cable loss at frequency |

| N_SMA_pairs | Number of SMA connector pairs |

| Loss_per_SMA_pair_dB | Typical 0.05-0.2 dB |

| Other_connector_loss_dB | BNC, N, MCX losses |

| Total_link_loss_dB | Combined loss |

| Tx_power_dBm | Transmit power |

| Required_Eb_N0_margin_dB | Design margin |

| Resulting_margin_dB | Remaining margin |

The calculations are intentionally simple.

Cable_loss_dB = Cable_attenuation_dB_per_m × Cable_length_m

Connector_loss_dB = (N_SMA_pairs × Loss_per_SMA_pair_dB) + Other_connector_loss_dB

Total_link_loss_dB = Cable_loss_dB + Connector_loss_dB

Resulting_margin_dB = Tx_power_dBm − Total_link_loss_dB − Required_Eb_N0_margin_dB

What this table does well is expose how quickly “small” connector losses add up. Two SMA pairs at 0.15 dB each do not look significant on paper. Combined with a longer SMA coax cable run and an antenna mismatch, they can push a marginal design into failure territory.

Engineers who have worked through RG316 cable loss and routing behavior often find that the connector contribution becomes more visible once cable losses are already well understood.

Treat SMA connectors and cables as a single assembly, not separate parts

A recurring pattern in RF troubleshooting is this: cable loss is modeled carefully, antenna performance is measured, and regulatory limits are respected. The connector is assumed to behave ideally because it “always has before.” When issues appear late, the connector is revisited only after everything else has been ruled out.

In practice, SMA connectors and cables behave as a coupled system. A well-chosen RG316 jumper terminated with a connector designed specifically for that cable behaves predictably. The same cable with a generic or mismatched SMA termination may not.

This is also why short SMA male to SMA male cable jumpers sometimes behave worse than longer ones. The cable loss is low, but the connector interfaces dominate the RF behavior. Understanding that balance is key when designing compact RF paths inside enclosures or between stacked boards.

Where this fits in the larger SMA picture

This section intentionally bridges cable-centric and connector-centric thinking. If you approach SMA selection only from the connector side, you miss how cable geometry constrains performance. If you approach it only from the cable side, you miss how the interface defines repeatability.

The remaining sections will expand outward again—into mechanical form factors, alternative connector families such as MCX connector and MMCX connector, and long-term reliability topics that show up after deployment rather than during design.

How can you choose between straight, right-angle, bulkhead, and panel SMA connectors?

Figure 7 appears in the section discussing mechanical form factors, explaining that shape choice is not just a packaging problem but also affects electrical performance and reliability. It compares the pros and cons: straight connectors are most predictable, right-angle solves space constraints but introduces small discontinuities, and bulkhead/panel-mount involves additional constraints like mounting, grounding, and sealing.

Mechanical form factor is often treated as a packaging problem. In RF systems, it is also an electrical and reliability decision. The shape of an SMA connector influences how stress is transferred into the cable, how repeatable the mating interface remains, and how tolerant the system is to handling over time.

Straight SMA connectors are the most electrically predictable. They preserve coaxial symmetry and tolerate repeated mating better than many alternatives. When space allows, a straight connector combined with a gentle cable bend usually produces the most stable long-term behavior. This is especially true for short internal jumpers, where connector effects dominate over cable loss.

Right-angle SMA connectors solve real problems when vertical clearance is limited or when the cable must exit parallel to a PCB or enclosure wall. They are common on RF modules and compact enclosures. The trade-off is subtle but real: the bend introduces a small discontinuity, and mechanically the joint often sees higher stress during handling. In systems that are frequently serviced, this matters more than the nominal insertion loss number.

Bulkhead and panel-mount SMA connectors introduce another layer of constraints. Thread length, panel thickness, grounding strategy, and sealing all interact. A bulkhead SMA used as an antenna feed-through becomes part of the enclosure design, not just the RF chain. If you are already budgeting loss carefully on the cable side, it makes sense to think about the bulkhead interface as another connector pair rather than a passive wall penetration.

In lab environments, SMA layout decisions affect productivity. Panel spacing, wrench clearance, and labeling determine whether connectors are tightened consistently or abused out of convenience. These details do not appear in simulations, but they show up quickly during validation.

Where do SMA connectors sit among other RF connector families (BNC, N, MCX, MMCX)?

SMA connectors rarely exist alone in a system. They coexist with other RF interfaces, each optimized for a slightly different set of constraints.

Compared with BNC, SMA favors frequency capability and mechanical compactness over quick connect and disconnect. BNC works well for video and lower-frequency test setups, but its bayonet mechanism becomes less predictable at higher microwave frequencies. SMA trades speed for repeatability.

Compared with N connectors, SMA prioritizes size and convenience. N connectors handle higher power and harsher outdoor environments more gracefully, which is why they dominate long outdoor feeder runs. SMA is more common closer to the radio, where space is limited and power levels are lower.

Compact RF modules often replace SMA entirely with MCX connector or MMCX connector interfaces. These snap-on connectors reduce footprint and work well with very thin coax. Their weakness is mechanical robustness. In systems that see vibration or frequent reconnection, SMA still tends to age more gracefully.

Adapters connect these families when needed, but they are rarely neutral. Each adapter adds loss and reflection, and more importantly, it adds another mechanical interface that can loosen or wear. Adapters are excellent tools for validation and bring-up. If an adapter becomes permanent, that is usually a sign the cable assembly or panel interface should be redesigned instead.

How should you design SMA connector interfaces for antennas, jumpers, and test points?

Antenna interfaces are where SMA connectors see the harshest combination of handling, environment, and electrical sensitivity. Routing from an antenna bulkhead to the RF front end often looks trivial on paper. In practice, short internal SMA coax cable runs dominate the RF behavior because the antenna and radio are already fixed.

Using RG316 coaxial cable for these runs is common because it tolerates heat and tight bends. What matters is strain relief. SMA connectors do not tolerate being used as structural anchors. If the cable moves, the connector should not.

Jumpers deserve similar attention. Short SMA male to SMA male cable assemblies are often assumed to be harmless because they are short. In reality, connector loss and connector condition dominate these links. This is why very short jumpers sometimes behave worse than longer ones: the cable contributes little loss, so the interface does most of the work.

Test points introduce a different set of trade-offs. Board-edge SMA ports are invaluable during validation, but they see mating cycles far beyond what production connectors experience. If a test port is expected to survive hundreds of connections, it should be treated differently from a production antenna interface. Planning for replacement or isolation early avoids measurement drift later.

What reliability, mating, and ESD checks keep SMA connectors stable over time?

Reliability issues around SMA connectors rarely appear as immediate failures. They accumulate.

Torque consistency matters more than nominal torque value. A connector tightened inconsistently ages faster than one tightened slightly below its maximum rating but done the same way every time. This is why torque wrenches remain standard practice in RF labs long after other hand-tight interfaces have disappeared.

Environmental exposure changes priorities. Outdoor installations combine moisture, temperature cycling, and corrosion. In those cases, material choice, plating quality, and sealing features matter as much as electrical performance. Stainless-steel SMA connectors often appear in these designs not because they are electrically superior, but because they survive longer.

ESD is another underappreciated factor. SMA connectors at antenna ports are natural discharge paths. Without proper protection, energy couples directly into the RF front end. Surge suppression, grounding strategy, and connector placement all influence how much of that energy reaches sensitive circuitry. Treating the SMA interface as part of the protection strategy rather than a passive opening makes systems more robust.

What market and technology trends are shaping future SMA connector use?

Despite frequent predictions of obsolescence, SMA connectors remain deeply embedded in RF hardware. Growth in IoT, private cellular networks, and satellite communication continues to favor interfaces that are compact, repeatable, and widely supported.

At the same time, frequency requirements are rising. Precision variants that share mechanical lineage with SMA—such as 3.5 mm and 2.92 mm interfaces—are increasingly used where performance beyond 26.5 GHz is required. These connectors coexist with SMA rather than replacing it, forming a layered ecosystem where each interface serves a specific range of frequencies and use cases.

Field data continues to show that many RF failures attributed to “mystery loss” trace back to connector wear, contamination, or assembly variation. As systems scale, inspection and replacement practices around SMA interfaces become more important, not less.

Frequently asked questions

Are all SMA connectors interchangeable across brands?

Electrically, most standard 50-ohm SMA connectors will mate, but tolerances, plating, and dielectric geometry vary. Mixing low-cost SMA parts with precision connectors often increases reflection and accelerates wear.

How do I choose an SMA connector for RG316 or RG58?

Start with the cable geometry. The connector must be designed specifically for that cable diameter and dielectric structure. Mechanical fit alone is not enough to preserve impedance.

When is a right-angle SMA connector the better choice?

Right-angle connectors help when height or routing constraints dominate. If space allows, a straight connector with a controlled cable bend usually offers better long-term stability.

Can SMA be mixed with MCX or MMCX using adapters?

Yes, and this is common during validation. Each adapter adds loss and another mechanical interface, so long adapter chains should be avoided in final designs.

How many mating cycles can SMA connectors handle?

Typical SMA connectors are rated for roughly 500 cycles under proper torque and cleanliness. Lab setups can reach this limit faster than expected.

Is SMA still suitable for 5G designs?

For sub-6 GHz 5G and most IoT systems, SMA remains a practical choice. At mmWave frequencies, precision connectors derived from the SMA form factor are usually preferred

Closing context

Across all three sections, the pattern is consistent. SMA connectors behave well when they are treated as part of the RF system, not as interchangeable hardware. Cable choice, connector geometry, torque, environment, and usage patterns interact in ways that are easy to ignore early and difficult to correct late.

If this article succeeds, it does not convince readers to use SMA. It convinces them to stop assuming SMA is invisible.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.