SMA Male to Male Cable Jumpers Guide

Jan 24,2025

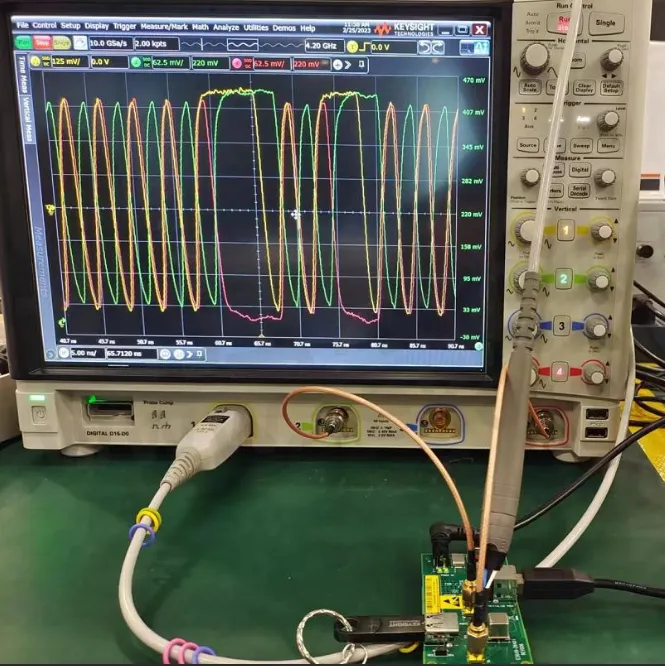

Figure 1 is typically used to illustrate the typical application of SMA male-to-male cables in RF system debugging or integration, highlighting their often overlooked but essential role in actual connections.

Where does an sma male to male cable help?

An sma male to sma male cable almost never shows up on a system diagram.

It appears later—after the radio already works, after the enclosure looks “mostly done,” and after someone realizes two SMA female ports need to talk to each other right now.

That timing is part of the problem.

Because the jumper is short and passive, it’s easy to assume it doesn’t matter much. Yet in RF labs and early-stage products, this cable often sits at the most sensitive point in the chain: directly between two active ports with no buffering in between.

If a measurement shifts when a cable is nudged, or a result can’t be reproduced after swapping “the same kind of jumper,” the explanation is usually simple. The cable was never neutral.

A male-to-male SMA jumper exists for one job only: to connect two SMA female ports directly while disturbing the RF path as little as possible. Everything else—loss, stability, durability—flows from that role.

Map typical RF lab paths that rely on male–male jumpers

Look at how RF labs actually operate, not how block diagrams pretend they do.

Most instruments expose SMA female connectors by default. VNAs, spectrum analyzers, signal generators, power sensors—all expect the mating connector to be male. Many DUTs do the same, especially evaluation boards and small RF modules intended for lab use.

That symmetry is where the sma male to sma male cable becomes unavoidable.

The most common case is instrument-to-DUT. A short jumper bridges the analyzer port and the device under test directly. No feedthroughs, no panel transitions, no unnecessary interfaces. The signal path is simple, which is exactly what you want when you’re trying to understand behavior rather than fight setup artifacts.

Instrument-to-instrument links show up just as often. Attenuators, amplifiers, and filters get rearranged constantly during characterization. Using a single jumper keeps the chain readable. Start stacking adapters instead, and small losses and mismatches creep in quietly.

Calibration chains rely on these jumpers too. During SOLT or TRL calibration, repeatability matters more than convenience. Labs that care about consistency usually keep a small set of trusted male-to-male jumpers and avoid mixing them with general-purpose cables. This practice lines up closely with broader SMA handling rules discussed in our guide on SMA coaxial cable structure and selection.

Connect module-to-module and board-to-board links with SMA jumpers

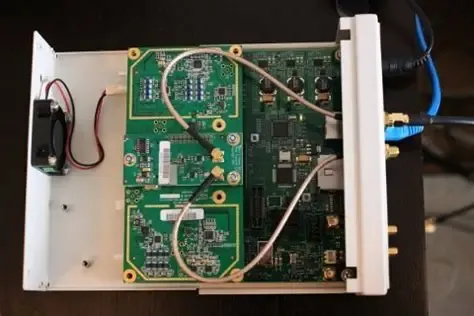

Figure 2 emphasizes the practicality of SMA male-to-male jumpers during prototyping, supporting reversible connections and facilitating debugging and architectural adjustments.

The same jumper doesn’t stay confined to the lab bench.

During development, sma jumpers often migrate into products long before the RF layout is finalized. A Wi-Fi or cellular module might expose an SMA connector. A front-end board or filter block might do the same. A short male-to-male cable makes the connection reversible while the architecture is still in flux.

Board-to-board links follow a similar pattern. During debugging or validation, a jumper provides a quick RF bridge between subassemblies. When something changes—and something always does—the cable can be replaced without cutting coax or re-terminating connectors.

In these situations, the sma cable isn’t just carrying RF energy. It’s buying flexibility. The tradeoff is that flexibility introduces another variable into the system, which is why cable choice and handling start to matter much earlier than most teams expect.

If those jumpers eventually leave the lab and live inside an enclosure, routing and temperature considerations become more relevant—topics we cover separately in our discussion of RG316 internal routing and high-temperature reliability.

Contrast sma male to male cable vs sma male to sma female cable roles

Figure 3 explains the physical construction of SMA male-to-male cables and their core function as a "jumper"—providing direct and simple RF path connections.

Figure 4 contrasts with Figure 3, emphasizing that SMA male-to-female cables are primarily used for interface relocation, not direct port interconnection, to avoid routing issues or performance degradation.

A sma male to sma female cable usually acts as an extension. It relocates an SMA interface—from a PCB to a panel, or from inside an enclosure to the outside. Mechanically, it behaves more like a feedthrough than a jumper, even though electrically it’s still a 50-ohm sma coaxial cable.

Using a jumper where an extension belongs often leads to awkward routing and stressed connectors. Using an extension where a jumper would suffice quietly adds length and loss. The difference isn’t dramatic on paper, but it becomes obvious once systems move out of the lab and into real hardware.

How to choose cable types for SMA jumpers

Connector gender determines how ports mate.

Cable choice determines how that connection behaves after weeks of handling.

Compare rg316 coaxial cable with other 50-ohm families

For short jumpers, rg316 coaxial cable shows up so often that many engineers stop questioning it. That popularity comes from practicality rather than perfection.

RG316 is thin enough to route easily and flexible enough to tolerate repeated bending. Its PTFE dielectric handles heat well, which matters in labs where rework and hot components are common. Those traits make it forgiving in environments where cables are moved constantly.

Other 50-ohm options exist, each with tradeoffs:

RG174 is thinner and easier to squeeze into tight spaces, but its higher attenuation and reduced durability make it less comfortable as a daily-use lab jumper. RG58 lowers loss, especially at lower frequencies, but its stiffness can apply real torque to SMA ports. LMR-100-class cables reduce loss further, yet their limited flexibility makes them feel closer to semi-permanent wiring than a jumper.

For most sma male to sma male cable assemblies under about a meter, RG316 lands in a workable middle ground. It’s not the lowest-loss option, but it tends to fail gracefully. As frequency increases or runs get longer, the balance shifts—at which point it helps to step back and review the broader RG landscape, as outlined in our RG cable guide.

Link sma coax cable structure to loss and durability

From the outside, two SMA jumpers can look identical. Internally, they may behave very differently.

Center conductor construction is one factor. Stranded conductors usually tolerate flexing better than solid ones, which is why they’re common in jumper cores. Dielectric material matters as well. PTFE offers stable electrical properties across temperature, while foam dielectrics trade some stability for lower attenuation.

Shielding design plays a quieter role. Single-braid shields can work, but double-braid or braid-plus-foil constructions tend to survive repeated handling better over time.

In practice, failures rarely happen in the middle of the cable. They show up near the connector, where bending is tightest and stress concentrates. That’s why jacket material, strain relief, and minimum bend radius often matter more than the headline loss number on a datasheet.

Decide when to treat sma rf cable as a test-grade jumper

Not every measurement needs a premium cable. Many tasks—basic power checks, functional validation, quick comparisons—work fine with a standard RG316-based jumper.

Some workflows are less forgiving.

Vector network analysis, phased-array testing, and calibration-heavy setups all care about phase stability. In those cases, cable movement alone can shift results. A purpose-built test-grade sma rf cable, with specified phase stability under flex, removes one more variable from the measurement loop.

They cost more. They also tend to save time, which is usually the scarcer resource.

Plan sma male to male cable length and loss

How to plan length and attenuation without guessing

In labs, jumper length decisions are rarely made with numbers first.

Someone reaches for “the shortest cable that fits,” plugs it in, and moves on.

That works—until it doesn’t.

At higher frequencies, or when multiple adapters sneak into the path, length stops being cosmetic. It becomes part of the measurement setup, whether you planned for it or not. This is especially true when an sma male to sma male cable sits directly between an instrument port and a sensitive DUT.

The goal isn’t to calculate loss down to the last decimal.

The goal is to stay inside a known budget so the cable never becomes the dominant uncertainty.

Define inputs for a lab-focused SMA jumper planner

Inputs that actually matter in real benches

Before touching formulas, it helps to agree on what you’re solving for. A practical lab planner doesn’t try to model everything. It focuses on what engineers can reasonably control.

Planner inputs

| Input | Description |

|---|---|

| Frequency_GHz | Operating frequency in GHz |

| Cable_Type | Core type, e.g. rg316 coaxial cable |

| Length_m | Planned jumper length |

| Attenuation_dB_per_m | Typical loss at target frequency |

| Max_Port_Loss_dB | Allowable loss budget at the instrument port |

| Num_Adapters | Extra SMA adapters in the path |

| Adapter_Loss_dB_each | Typical loss per adapter |

Most of these values don’t need to be perfect. Attenuation numbers can come from vendor datasheets or past measurements. Adapter loss can be conservative. What matters is consistency.

If you’re unsure why port loss budgets exist in the first place, it’s worth revisiting how insertion loss and impedance mismatch affect RF measurements—concepts summarized well in the general discussion of insertion loss on Wikipedia.

Calculate cable and adapter loss against the port budget

Simple math, useful conclusions

Once inputs are defined, the math is intentionally straightforward.

Cable loss

Cable_Loss_dB = Attenuation_dB_per_m × Length_m

Adapter loss

Adapter_Loss_dB = Num_Adapters × Adapter_Loss_dB_each

Total path loss

Total_Path_Loss_dB = Cable_Loss_dB + Adapter_Loss_dB

Margin to port limit

Margin_to_Limit_dB = Max_Port_Loss_dB − Total_Path_Loss_dB

Maximum recommended jumper length

Max_Length_m = (Max_Port_Loss_dB − Adapter_Loss_dB) / Attenuation_dB_per_m

None of this is exotic. What’s useful is applying it consistently.

Turn planner results into lab decisions

Where the math actually changes behavior

Once numbers are on the table, decisions usually fall into three buckets:

- Green margin (≥ 3 dB)

Keep the planned length. No action needed.

- Yellow margin (0–3 dB)

Shorten the jumper if practical, or remove an adapter.

- Red margin (< 0 dB)

Change the plan. Shorter cable, lower-loss core, or a direct custom sma male to male cable instead of stacked adapters.

What often surprises teams is how quickly adapters eat margin. Electrically, each one adds only a small loss. Mechanically, each one adds another interface that can loosen, tilt, or age. Reducing adapter count is frequently the cleanest fix.

Protect RF ports when using SMA jumpers

How to avoid turning cables into consumables

Ports are expensive.

Jumpers are not.

Yet in many labs, ports take the abuse while cables get replaced. That’s backwards.

Use torque and strain relief to save instrument ports

Hand-tight feels convenient, but it’s inconsistent. Some people under-tighten. Others overdo it.

Using a calibrated SMA torque wrench doesn’t slow work down as much as people fear. More importantly, it keeps mating force predictable, which protects both the instrument port and the connector on the sma cable itself.

Strain relief matters just as much. Avoid tight bends right at the connector. Support heavier cables so they don’t hang off the port. These habits sound mundane, but they’re the difference between a port that lasts years and one that becomes intermittent in months.

Mechanical wear at SMA interfaces is well documented, and the basic mating principles align closely with connector interface standards published by organizations like the IEC and summarized in connector overviews such as the SMA connector entry on Wikipedia.

Limit how often a single sma male to sma male cable is reused

Even high-quality SMA connectors have finite mating cycles. Labs that rely heavily on a few favorite jumpers often discover this the hard way—through intermittent behavior that’s difficult to reproduce.

A practical approach is to treat high-use jumpers as semi-consumables:

- Label critical cables

- Track approximate insertion counts

- Retire jumpers before they become suspicious

This matters more for short, frequently handled sma male to sma male cable assemblies than for longer runs that rarely move.

Decide when to upgrade to ruggedized or phase-stable sma rf cable

Some setups are gentle. Others are not.

If a jumper is constantly repositioned, routed around fixtures, or flexed during measurements, mechanical robustness becomes as important as electrical specs. In phase-sensitive measurements, stability under flex becomes critical.

That’s where ruggedized or phase-stable sma rf cable assemblies make sense. They don’t eliminate loss, but they reduce variability. And in measurement work, variability is often the real enemy.

Deploy sma male to male cables in products

Figure 5 emphasizes that in later product integration stages, SMA jumpers must withstand harsher mechanical and thermal environments, requiring selection and installation considerations for long-term reliability beyond lab convenience.

A jumper that behaves well on a lab bench doesn’t automatically behave well inside a product.

Once the enclosure is closed, the environment changes. Cables stop being freely routed. Heat builds up. Vibration appears. And access becomes limited. At that point, a sma male to sma male cable is no longer a convenient lab tool—it becomes part of the hardware.

That shift is where many late-stage RF issues quietly begin.

Bridge removable RF modules with short jumpers

One place where male-to-male SMA jumpers continue to make sense is between removable RF modules and the rest of the system.

Industrial gateways, embedded radios, and development-focused platforms often rely on plug-in RF modules. Using a short jumper keeps those modules replaceable without redesigning the RF path every time something changes.

The key detail is length. Inside a product, jumpers tend to be longer than they need to be “just in case.” That extra slack usually turns into tight bends once the enclosure is assembled. Keeping the sma male to male cable as short as practical reduces both loss and mechanical stress.

Teams that ignore this often end up compensating later—by adding attenuation in software, derating performance, or quietly accepting reduced margin.

Combine internal jumpers with external sma antenna cable

Inside enclosures, not all SMA cables are doing the same job.

A pattern that shows up repeatedly in robust designs is role separation. Internal connections are handled by short male-to-male jumpers. Anything that needs to reach a panel, bulkhead, or antenna uses a dedicated sma antenna cable designed for that environment.

This separation keeps internal jumpers protected from movement and external stress. It also simplifies service. Antennas can be replaced without disturbing internal RF routing, and internal boards can be serviced without touching the antenna feedline.

Designers who blur this boundary often discover that the cable doing “everything” ends up doing nothing particularly well. That’s one reason many teams revisit their SMA layout once they step back and look at the system as a whole, not just individual links—something that tends to surface during broader reviews like those described in the SMA coaxial cable structure and selection guide.

Avoid overusing jumpers where fixed coax runs are better

Jumpers feel safe because they’re replaceable. That logic breaks down when they’re used everywhere.

In products that won’t be opened frequently, a chain of short jumpers is usually worse than a single fixed coax run. Electrically, the difference may look small. Mechanically, it’s not. Every connector pair adds tolerance stack-up, wear, and another chance for something to loosen.

A compromise that works well in practice is one fixed coax run combined with one short jumper. The fixed run handles routing and strain. The jumper absorbs alignment and assembly variation. It’s not elegant, but it’s predictable.

What market trends affect SMA jumper choices?

Growing dependence on short RF jumpers

RF systems are becoming denser. More radios per device. More test points per board. More validation per unit.

That trend quietly increases the number of short SMA jumpers used per project. Labs that once relied on a handful of cables now manage dozens. Production lines rely on repeatable jumper performance to keep automated tests stable.

As a result, sma male to sma male cable assemblies are no longer treated as generic accessories. They’re specified, tracked, and sometimes even qualified, much like other RF components.

Higher frequencies tighten tolerances

At lower frequencies, small losses and mismatches hide easily. At higher frequencies, they don’t.

As testing moves further into multi-GHz ranges, cable behavior that used to be ignored—phase drift under flex, connector repeatability, small impedance changes—starts showing up in measurements. That’s why higher-spec sma rf cable assemblies are becoming more common even in non-research environments.

This isn’t driven by theory. It’s driven by engineers trying to reproduce results and failing.

OEM shift toward standardized jumper assemblies

Another quiet change is organizational.

Instead of assembling jumpers ad hoc, many OEM teams now define a small number of standard SMA jumper configurations and source them pre-assembled. The value moves away from raw cable and toward termination quality, inspection, and consistency.

From an engineering perspective, this reduces one variable. From a manufacturing perspective, it simplifies inventory. Both sides tend to prefer fewer surprises.

Turn SMA jumper experience into a repeatable workflow

Start from constraints, not convenience

A reliable workflow starts by asking what the ports can tolerate—power, loss, frequency—before asking what cable is nearby.

Once those constraints are clear, the choice of sma male to sma male cable becomes much narrower. Length, cable type, and connector quality stop being arbitrary.

Define a small set of standard sma cable configurations

Instead of choosing cables one by one, many teams benefit from defining a few standard jumper profiles:

- Short lab jumpers for bench work

- Internal jumpers for enclosed systems

- More rugged jumpers for validation or field testing

Each profile includes cable type, length range, and expected handling. This doesn’t eliminate judgment, but it reduces friction and avoids repeated debates.

If RG316-based jumpers are part of those standards, documenting routing and temperature limits helps prevent misuse later. That’s especially relevant once jumpers move from open benches into confined enclosures, as discussed in more detail in the context of RG316 internal routing and high-temperature reliability.

Keep jumper decisions connected to the bigger RF picture

Jumpers don’t exist on their own. They sit between connectors, cables, antennas, and enclosures.

Treating sma male to sma male cable selection as part of a larger RF interconnect strategy makes systems easier to reason about—and easier to fix when something goes wrong.

FAQ — Lab-driven questions that come up repeatedly

Q1: Is it acceptable to connect two RF instruments directly using a sma male to male cable?

Yes. It’s common practice. Just confirm power levels, avoid tight bends at the connector, and account for the jumper’s loss when interpreting results.

Q2: How often should heavily used SMA jumpers be replaced?

There’s no universal number. Replace them when insertion force changes, connectors feel loose, or measurements become inconsistent without another explanation.

Q3: Is rg316 coaxial cable always sufficient for lab jumpers?

Often, but not always. RG316 balances flexibility and durability, but higher frequencies or longer runs may justify lower-loss or phase-stable alternatives.

Q4: When does phase stability actually matter in practice?

It matters when relative phase is part of the measurement—VNA work, phased arrays, and calibration-heavy setups.

Q5: Inside an enclosure, when should I use a male-to-male jumper instead of a male-to-female extension?

Use male-to-male jumpers to connect two active internal ports. Use male-to-female cables to relocate a port to a panel or enclosure wall.

Q6: How many adapters are reasonable in a jumper chain?

One or two at most. Beyond that, a custom jumper with the correct connectors is usually the cleaner solution.

Q7: What’s a quick way to sanity-check a batch of new SMA jumpers?

Inspect connectors, measure insertion loss at your operating frequency, and gently flex the cable while watching the measurement. Large variation is a warning sign.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.