RG316 Coaxial Cable Specs, Loss & Uses

Jan 16,2025

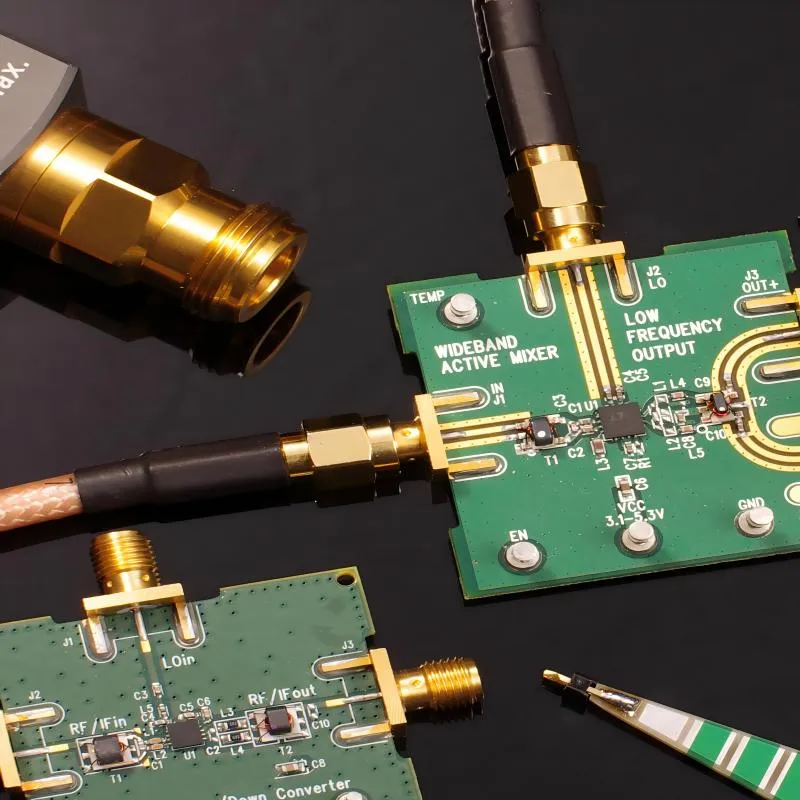

This image appears at the beginning of the document, aiming to visually introduce the RG316 cable. It most likely shows a spool of RG316 cable or a close-up of the cable itself, establishing a visual recognition of the subject and echoing the text's point that "cable choices rarely get the attention they deserve."

In RF projects, cable choices rarely get the attention they deserve. Antennas spark debate. Radios trigger simulations. Enclosures go through endless revisions.

The cable? It usually slips in late, chosen because it fits.

That’s where rg316 coaxial cable quietly enters the picture.

It isn’t a universal solution, and it’s definitely not a low-loss feeder. Instead, RG316 occupies a narrow but important role in modern RF systems—one defined by temperature tolerance, mechanical flexibility, and short, controlled signal paths. Understanding where it fits is far more important than memorizing its datasheet.

Where does rg316 coaxial cable fit in RF?

This image is likely a diagram illustrating the typical application position of RG316 cable in modern RF systems. Based on the context, it probably depicts a simplified signal chain from "RF chip/module" to "external antenna/instrument," highlighting that RG316 is typically active in the segment between "short internal coax" and "panel connector," not as a long-distance feeder.

RG316 makes sense only when you stop thinking in terms of “best cable” and start thinking in terms of system position.

Most RF chains—whether in labs, IoT devices, or industrial equipment—follow a familiar structure:

RF chip or module → short internal coax → panel connector → external cable → antenna or instrument.

RG316 almost always lives inside that chain, not at the edges.

Map RF segments that naturally favor rg316 cable

This should be a product-related image that visually demonstrates a typical application of RG316 cable in real hardware design. Based on the context, it is likely a close-up photo showing the actual routing of RG316 cable inside a device (such as an IoT gateway, RF module, or industrial equipment). The image might focus on a classic "board-to-panel connection" scenario: one end of the cable is connected to an RF module or connector on the PCB, and the other end is connected to an SMA or N-type panel mount on the device enclosure. It showcases how RG316 achieves a clean and flexible signal transition in tight spaces, solving the problem where "thick coax is physically intrusive."

There are three RF segments where RG316 consistently earns its place.

First, board-to-panel connections. When an RF module sits several centimeters away from an SMA, N, or BNC bulkhead, routing becomes awkward. PCB traces are no longer practical, and thick coax is physically intrusive. RG316 bridges that gap cleanly.

Second, lab jumpers. On test benches, cables are bent, twisted, unplugged, and reconnected daily. Mechanical compliance matters as much as electrical behavior. RG316 survives this abuse better than many alternatives.

Third, thermally stressed zones. Power regulators, PAs, and dense digital sections generate heat. PVC-jacketed micro coax may survive briefly, but over time it hardens or drifts electrically. RG316’s PTFE/FEP construction tolerates these environments with far less aging.

If you’re mapping a system and asking “where does routing get tight, hot, or mechanically noisy?”—those are the natural landing zones for RG316.

Separate rg316 coaxial cable from other RG families

It’s tempting to lump RG316 in with every other 50 Ω coax. That shortcut causes design mistakes.

Yes, RG316, RG174, RG58, and even LMR families all nominally share the same impedance. Electrically, they can connect. Mechanically and thermally, they behave very differently.

RG316 stands out in three ways:

- Diameter: noticeably smaller than RG58, making tight routing realistic

- Bend behavior: more forgiving than most low-loss cables

- Temperature rating: far beyond PVC-based RG174

The cost of those advantages is loss. RG316 was never meant to carry signals across meters of distance. Treating it as a thin replacement for RG58 or LMR-200 is where expectations break.

If you need a broader perspective on how RG316 compares across the full RG and LMR landscape, it helps to step back to a system-level view like the one in the RG Cable Guide. That context makes RG316’s role much clearer.

Identify “fit-first” applications for compact rg316 runs

Certain applications almost select RG316 by default—not because it’s optimal on paper, but because alternatives create more problems than they solve.

RF test and measurement jumpers are the most obvious example. Short SMA-to-SMA assemblies made with RG316 strike a balance between flexibility and repeatability. On VNAs, spectrum analyzers, and signal generators, that balance matters more than shaving a fraction of a dB.

Another common case is internal module-to-panel links. Inside compact enclosures, thicker cables fight with mounting hardware, airflow paths, and assembly tolerances. RG316 routes cleanly without stressing connectors or bending PCB launch points.

Finally, high-temperature pockets inside equipment deserve special mention. Even when ambient temperature seems reasonable, local hotspots around DC-DC converters or RF power stages can quietly exceed what small PVC cables tolerate long-term. RG316 survives here with far less drift.

If your design problem starts with “this needs to fit here,” RG316 is often the first cable worth evaluating.

When is rg316 better than other 50 ohm cables?

RG316 rarely wins a head-to-head loss comparison. That’s not the point.

The real question is whether its weaknesses actually matter in your application—or whether its strengths quietly reduce risk elsewhere.

Compare rg316 coax cable with RG174 and RG58

At ISM and Wi-Fi frequencies, attenuation data paints a predictable picture. RG58 offers lower loss but demands space. RG174 fits tighter but struggles with heat and long-term durability. RG316 lands in between electrically, but above both thermally.

At 2.4 GHz and 5.8 GHz, RG316’s loss per meter is clearly higher than RG58 and somewhat higher than RG174. Yet in short runs—tens of centimeters rather than meters—the difference often falls well below other system uncertainties, like connector quality or antenna mismatch.

This is why experienced engineers don’t ask “which cable has lower loss?” They ask “does this loss matter here?”

Check high-temperature and mechanical advantages of rg316

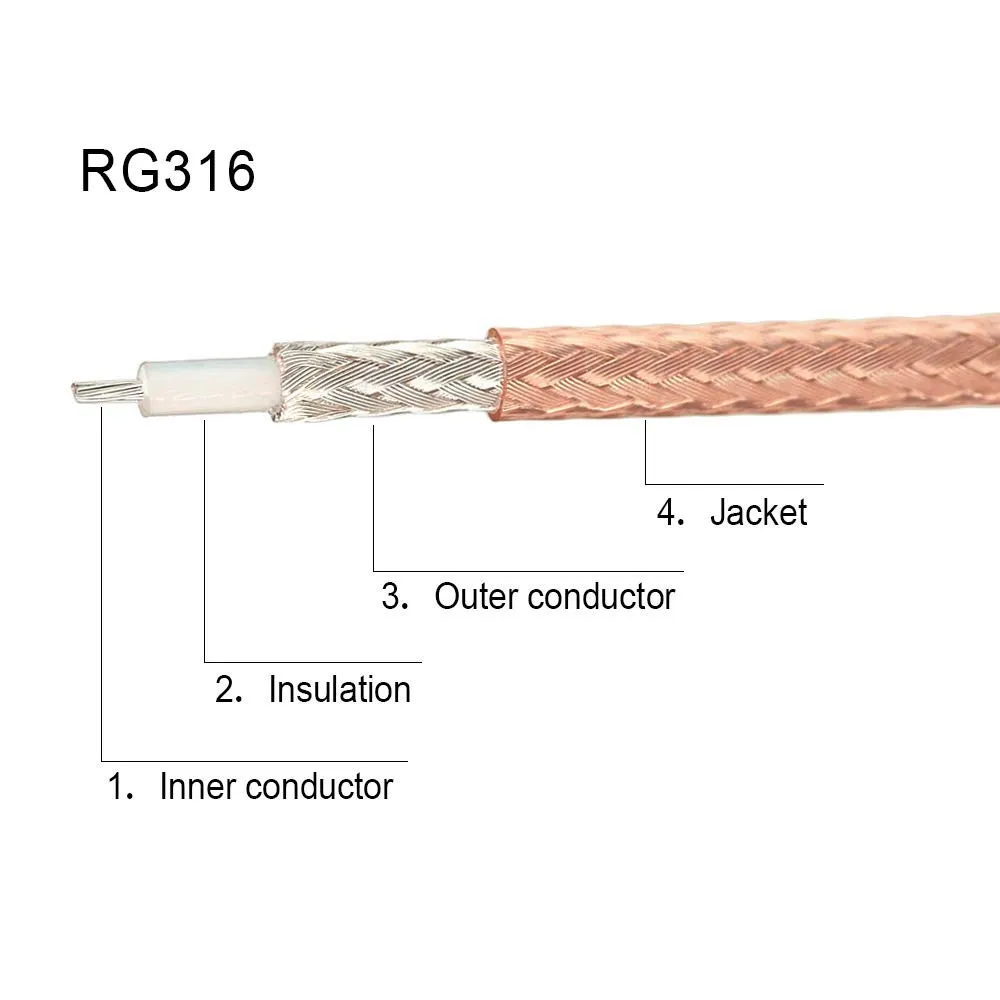

This image aims to explain the physical construction of RG316 and its resulting advantages. It is likely a cutaway diagram of the cable, clearly showing the layered structure: silver-plated copper conductor, PTFE dielectric, and FEP outer jacket. The image might be associated with a high-temperature environment (e.g., indicated by a thermometer or heat source icon), emphasizing how this material stack supports continuous operation above 150°C and maintains stable electrical properties.

Most RG316 constructions use silver-plated copper conductors, a PTFE dielectric, and an FEP outer jacket. That combination supports continuous operation well above 150 °C, with short-term tolerance even higher depending on the manufacturer.

In practice, this means RG316 ages gracefully. It doesn’t stiffen as quickly, and its dielectric properties remain stable under thermal cycling. In aerospace, defense, and automotive electronics, those traits matter more than headline attenuation numbers.

One practical observation from field work: when RG316 assemblies fail, the failure point is almost always the connector termination, not the cable body itself. That’s a sign the material stack is doing its job.

Decide when rg316 cable is “good enough” for loss

Loss becomes problematic only when length creeps upward.

At around 1.4–1.6 dB/m near 2.4 GHz, RG316 is entirely manageable for runs under a meter. At 5.8 GHz, margins tighten faster, but short jumpers still remain viable.

Once distances move beyond roughly one meter, RG316 stops being a sensible choice. That’s where thicker, lower-loss cables should take over as feeders—while RG316 remains at the ends, solving routing and thermal problems rather than transmission efficiency.

If your system already struggles with link margin, RG316 won’t save it. If your system is mechanically constrained or thermally stressed, RG316 often prevents problems you won’t see until much later.

How do you estimate loss and power for rg316?

Loss estimation is where RG316 decisions most often drift off course. Some designers assume it behaves like a thinner RG58 and underestimate attenuation. Others glance at a single datasheet number, panic, and rule it out entirely. Neither approach reflects how RG316 is actually used in real RF systems, where cable length is short, routing is constrained, and mechanical reliability often matters more than absolute loss.

A better approach is to work with frequency-band ranges and conservative assumptions, then check those numbers against the actual link budget. This avoids false precision while still keeping the design grounded.

Use band-based attenuation numbers for rg316 coaxial cable

Across multiple manufacturers and independent measurement sources, RG316 attenuation does not vary wildly, but it is also never a single exact value. Construction details such as braid coverage, silver plating thickness, and jacket formulation all contribute to small differences. From a system perspective, those differences rarely justify chasing the “best” number on paper.

For practical planning, engineers tend to rely on rounded ranges that slightly overestimate loss rather than underestimate it. Typical values used in real designs are shown below.

| Frequency | Typical attenuation (dB/m) |

|---|---|

| ~100 MHz | 0.3 – 0.4 |

| ~1 GHz | 0.8 – 0.9 |

| 2.4 GHz | 1.4 – 1.6 |

| 5.8 GHz | 2.3 – 2.6 |

These ranges follow the expected behavior of small-diameter coaxial cables, where both conductor and dielectric losses rise with frequency. If you need a theoretical refresher on why this scaling occurs, the background discussion on coaxial cable fundamentals explains the mechanism clearly without drifting into vendor-specific claims.

In practice, when two sources disagree, experienced engineers simply design with the higher number and move forward. The time saved usually outweighs the fractional dB gained by optimistic assumptions.

RG316 Loss & Power Budget Planner

Rather than memorizing attenuation charts, it is far more useful to apply a simple planner that answers one question: Is this RG316 segment acceptable in the context of my overall link budget?

RG316 Coaxial Cable Loss & Power Budget Planner

The planner starts with a small set of inputs that are already known during early design.

- frequency_ghz: operating frequency, such as 0.9, 2.4, or 5.8

- length_m: physical length of the RG316 segment

- connectors_count: number of mated interfaces along the path

- allowed_loss_db: maximum loss allocated to this segment

- tx_power_w: transmit power at the source

To keep the calculation conservative but simple, the planner uses a reference attenuation at 1 GHz of approximately 0.85 dB/m, then scales loss linearly with frequency:

loss_db_per_m(f) ≈ loss_db_per_m_1ghz × (f / 1 GHz)

This approximation is not exact physics, but it tracks real RG316 behavior closely enough for engineering decisions. Connector loss is estimated at 0.15 dB per interface, assuming reasonably clean SMA-class connections. In heavily used lab environments, this number can creep higher, which is why margin matters.

Total insertion loss is then calculated as:

total_loss_db = loss_db_per_m(f) × length_m + 0.15 × connectors_count

The planner checks whether this value stays within the allocated loss budget. It also performs a basic power sanity check using typical RG316 power-handling limits, which at around 2.4 GHz are commonly in the 70–80 W range and decrease with frequency. This trend aligns with general RF transmission-line heating behavior discussed in transmission line theory, even though individual cable ratings depend on construction details.

If both loss and power checks pass, the planner reports remaining margin. If either fails, the recommendation is straightforward: shorten the RG316 run or redesign the path so a thicker, lower-loss cable handles the longer distance while RG316 remains only as a short jumper.

Apply the planner to lab jumpers and embedded rg316

When applied to real scenarios, the planner quickly shows why RG316 works well in its intended role. At 2.4 GHz, a 1 m RG316 jumper carrying 1 W with two connectors typically stays under 2 dB of total loss, which is acceptable in most lab and embedded links. At 5.8 GHz, a 0.25 m RG316 segment carrying 100 mW shows modest loss and enormous power margin, making it a safe and predictable choice.

What these examples highlight is not fragility, but sensitivity to length. RG316 behaves consistently as long as it remains short.

How can you route and terminate rg316 for reliability?

Keep bend radius and strain within safe limits

RG316 is flexible, but it is not immune to damage. Repeated sharp bends, especially immediately at the connector exit, gradually deform the dielectric and redistribute braid tension. The result is often a slow increase in insertion loss that gets misdiagnosed as a connector problem.

A simple rule helps: never allow the tightest bend to sit directly at the connector. A short straight relief section reduces long-term stress dramatically and costs almost nothing in space.

Anchor rg316 cable near each connector or bulkhead

Connectors are not structural elements. In enclosures, RG316 should always be anchored near SMA, N, or BNC interfaces using tie points, clamps, or heat-shrink strain relief. This prevents vibration, handling, or accidental pulls from transferring force into the termination.

On test benches, this practice is even more important. Lab cables see far more mating cycles than production assemblies, and anchoring often doubles their usable life.

Protect rg316 from heat, vibration, and moisture in enclosures

Although RG316 tolerates high temperatures, good design still minimizes unnecessary exposure. Maintain clearance from power components when possible, and avoid pressing the cable directly against heatsinks. In automotive, aerospace, or industrial equipment, combine RG316 with grommets, vibration damping, and basic sealing to prevent fretting and moisture ingress.

These precautions are not unique to RF design; they mirror best practices from general industrial cabling. The physics is the same—the frequencies are just higher.

Where is rg316 coax cable used in real products?

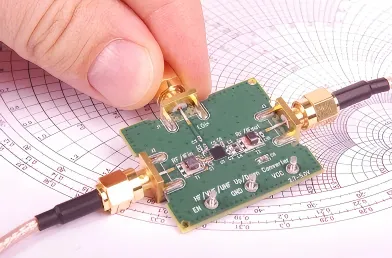

This image is a collection of application scenarios, showing the use of RG316 in various real-world products and environments. It may include three or four small illustrations: (1) SMA-to-SMA jumpers on a test bench connecting instruments and devices, (2) short cables inside a compact IoT gateway or Wi-Fi access point connecting the RF module to the antenna port, (3) short transitions between modules as part of a harness in aerospace or automotive electronics. This image visually demonstrates the practicality and reliability of RG316 when "several constraints collide at once."

RG316 rarely shows up as a highlighted component in product documentation, but it appears again and again once designs leave the schematic and turn into physical hardware. It tends to live in the places engineers don’t talk about much: short transitions, awkward corners, and thermally uncomfortable zones where “better on paper” cables create real-world problems.

What makes RG316 useful is not that it excels at any single metric, but that it stays predictable when several constraints collide at once.

Use rg316 jumpers in RF test and measurement labs

On RF test benches, RG316 is most often encountered as short SMA-to-SMA jumpers connecting instruments to DUTs. These cables live a rough life. They are bent daily, dragged across benches, unplugged mid-measurement, and occasionally asked to survive next to warm equipment racks.

In this environment, absolute loss is rarely the limiting factor. Mechanical stability and repeatability matter more. A jumper that measures 0.3 dB better on day one but drifts after a few weeks is less useful than a slightly lossier cable that behaves the same month after month.

Many labs quietly standardize on a handful of RG316 jumper lengths for routine measurements and reserve lower-loss cables for calibration or reference paths. This reduces variability and makes it easier to spot real system changes rather than cable-induced noise. If you are working specifically with jumper selection and length limits, the discussion in RG316 jumper length and loss planning goes deeper into how short RG316 assemblies age under repeated use.

Integrate rg316 into IoT and Wi-Fi antenna harnesses

Inside compact IoT gateways and Wi-Fi access points, RG316 often serves as the bridge between an RF module and an external antenna connector. PCB traces are rarely practical beyond a certain distance, and thicker coaxial cables quickly become a mechanical liability inside small enclosures.

RG316’s value here is its willingness to bend around obstacles without fighting the enclosure or stressing the connector. Loss is real, but in most designs the internal run is short enough that it stays within budget. Engineers typically accept that trade-off, then recover margin elsewhere in the system.

A common pattern is to let RG316 handle the internal transition and hand off to a thicker, lower-loss cable once the signal exits the enclosure. This “thin inside, thick outside” approach shows up frequently in Wi-Fi hardware and is discussed more broadly in the Wi-Fi antenna cable guide, where internal routing constraints often dominate early decisions.

Apply rg316 in aerospace, defense, and high-temperature systems

In aerospace, defense, and other high-reliability environments, RG316 is chosen less for convenience and more for confidence. Assemblies built to MIL-C-17 / MIL-DTL-17 specifications are expected to survive temperature cycling, vibration, and long service lives without changing their electrical behavior in subtle ways.

In these systems, RG316 usually appears as part of a harness rather than a standalone cable. It handles short transitions between modules, bulkheads, or test points where flexibility and thermal stability reduce stress on connectors and mating hardware. The focus is not on pushing frequency limits, but on ensuring the RF path behaves the same after years of operation as it did during qualification.

Which market trends matter for rg316 coaxial cable?

Understand cable assembly market expansion for OEMs

How do you standardize rg316 cable parts and docs?

Create a minimum spec template for every rg316 assembly

A minimal specification template avoids most of these issues. At a minimum, it should capture the cable family, impedance and frequency range, length and tolerance, connector types and orientations, plating details, temperature rating, and applicable standards such as MIL-DTL-17.

Without this information, two assemblies labeled “RG316 SMA jumper” may differ enough to matter in sensitive systems.

Build an internal rg316 jumper catalog for labs and products

Separating lab cables, production test cables, and field cables is a quiet but effective practice. Many teams adopt it only after chasing intermittent measurement issues caused by overused jumpers migrating into critical paths.

Maintaining a small internal catalog of approved RG316 jumper configurations simplifies reordering and replacement, especially in organizations with multiple labs or production sites.

Feed rg316 rules back into RG and SMA design hubs

Finally, RG316-specific guidance should not live in isolation. Length limits, acceptable loss ranges, connector count boundaries, and recommended use cases belong in broader RG and SMA design documentation.

Linking these rules back to system-level references such as the RG cable guide or enclosure-focused discussions like RG316 internal routing and high-temperature reliability helps keep decisions consistent across projects rather than rediscovered each time.

Practical FAQs

How long can an RG316 cable be at 5.8 GHz before loss becomes problematic?

At 5.8 GHz, attenuation rises quickly. Runs beyond roughly one meter often justify switching to a thicker feeder, keeping RG316 only as a short transition.

Is RG316 a good choice for low-power SDR work on the bench?

For short runs at tens to hundreds of milliwatts, RG316 performs well. Connector condition usually matters more than cable power handling in this range.

How do I tell if an RG316 jumper has been over-bent or stressed?

Common signs include jacket discoloration, visible deformation near bends, or a sudden increase in measured insertion loss.

Can I mix RG316 with a thicker LMR feeder in the same RF path?

Yes. This combination is common and effective when impedance is maintained and terminations are done correctly.

How often should RG316 cables in a production test rack be requalified?

Many teams recheck performance every 6–12 months, depending on usage, and keep a known-good reference cable for comparison.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.