RG316 Coax Cable Jumpers: Length & Loss

Jan 8,2025

This is typically a schematic or photo of a flexible RG316 coaxial cable with connectors (e.g., SMA) on both ends, placed below the article title. It visually represents the core component discussed in this article and implies that this seemingly insignificant, often added-late passive jumper is a key factor determining link performance margin at high frequencies. The image aims to establish an intuitive impression of RG316 jumpers for the reader, setting the stage for the subsequent in-depth discussion on its selection criteria, length limits, loss budget, and other practical issues.

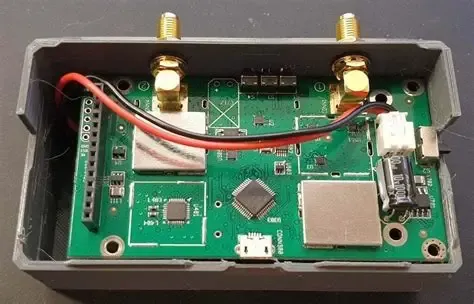

RG316 coax cable jumpers rarely get much attention during early design reviews. They’re small, flexible, inexpensive, and usually added after the radio, antenna, and enclosure already feel “locked in.” That timing is exactly why they cause trouble later.

On the bench, everything looks fine. The connector threads smoothly. The cable fits the space. RF power comes up. Then range feels a little shorter than expected. At higher bands, throughput drops first. Nobody suspects the jumper.

This guide is written for that moment—when you need to decide whether RG316 coax cable is the right tool, how long it can realistically be, and how to plan loss before it quietly eats into link margin. The focus is practical, based on how RG316 behaves in real enclosures, not how it looks on a datasheet.

If you’re still comparing all common RG families at a high level, it helps to skim a broader reference like the RG Cable Guide first. Here, we stay narrow and specific.

When should you choose RG316 coax cable instead of other RG types?

This schematic, likely in a panel or composite format, depicts several typical scenarios where RG316 jumpers excel: e.g., as a short jumper between an RF module and a bulkhead connector inside a compact metal enclosure; as an antenna lead under 0.5 meters inside a router or gateway; or in lab test setups where cables are frequently rerouted. This image aims to answer the question “When should you choose RG316 coax cable instead of other RG types?” It highlights the value of its small size and flexibility in space-constrained, assembly-access-critical scenarios, and implies that its primary role is “mechanical convenience,” with “electrical efficiency” being secondary.

Typical use cases for RG316 jumpers

In real projects, RG316 coax cable shows up most often in places where space, flexibility, or assembly access matter more than raw RF efficiency:

- Short internal jumpers between an RF module and a bulkhead connector

- Panel feed-through connections inside compact enclosures

- Antenna leads under 0.5 m in routers, gateways, and IoT devices

- Lab and test setups where cables are frequently rerouted or swapped

The small diameter and flexible FEP jacket make RG316 easy to dress cleanly. In tight metal boxes, that alone can justify its use.

Scenarios where RG316 is the wrong choice

There are also situations where RG316 quietly becomes the weakest link:

- Long cable runs, especially above 2.4 GHz

- Systems with sustained RF power rather than short bursts

- Outdoor routing where abrasion, UV, or moisture dominate

- Designs already struggling for link margin

In these cases, RG316 often “works” in the sense that the system powers up—but it leaves little margin for temperature drift, connector aging, or regulatory headroom.

A fast decision shortcut engineers actually use

Many teams rely on a simple rule of thumb before running any numbers:

If the run is short and the space is tight, start with RG316.

If loss or power margin is already tight, don’t.

That shortcut won’t replace proper planning, but it prevents most obvious misapplications early on.

How do you define band, run length, and loss budget before locking in RG316?

Map your operating band first

“RF” is not one frequency. Loss in RG316 increases quickly as frequency rises, so band definition matters more than cable length alone.

A practical way to group expectations looks like this:

- Sub-GHz (433 MHz, 868 MHz, 915 MHz): RG316 is forgiving

- 2.4 GHz: short runs are usually acceptable

- 5–6 GHz: length becomes critical very fast

If your design spans multiple bands, always plan for the highest one. Lower bands rarely rescue a poor high-frequency budget.

Convert link margin into allowable cable loss

Instead of asking “How long can my RG316 jumper be?”, flip the question:

How much loss can the cable afford before the system suffers?

Start from your system link budget. Subtract antenna mismatch, filter loss, and any known insertion losses in the RF path. What remains is your allowable cable loss, expressed in dB.

That number—not the cable datasheet—is what actually constrains RG316 length.

Account for connector loss early

Connector loss is small, but it adds up quietly. For planning purposes, many engineers assume:

- ~0.1–0.2 dB per connector pair

A short RG316 jumper with two or three connector interfaces can lose as much signal in metal as it does in copper.

RG316 Loss & Length Planner

| Parameter | Description |

|---|---|

| Input: Frequency band | 433 MHz / 915 MHz / 2.4 GHz / 5.8 GHz |

| Input: Target cable loss (dB) | Derived from link budget |

| Input: Cable length (m) | Or solve for maximum length |

| Input: Connector pairs | Each mated interface |

| Lookup: RG316 attenuation α(f) | ≈0.5 dB/m @433 MHz : ≈0.8 dB/m @915 MHz : ≈1.6 dB/m @2.4 GHz : ≈2.7 dB/m @5.8 GHz |

| Assumption | Connector loss ≈0.15 dB per pair |

| Output: Total loss | α(f) × length + connector loss |

| Output: Max recommended length | (Loss budget - connector loss) ÷ α(f) |

| Design note | If length exceeds result → consider RG58 or LMR-200 |

Many teams keep a version of this logic embedded in spreadsheets or internal calculators. It removes guesswork and keeps discussions objective.

If you’re deciding between RG families more broadly, the comparison in the Coaxial Cable Ultimate Guide provides useful context.

How is RG316 coax cable built and which specs actually matter?

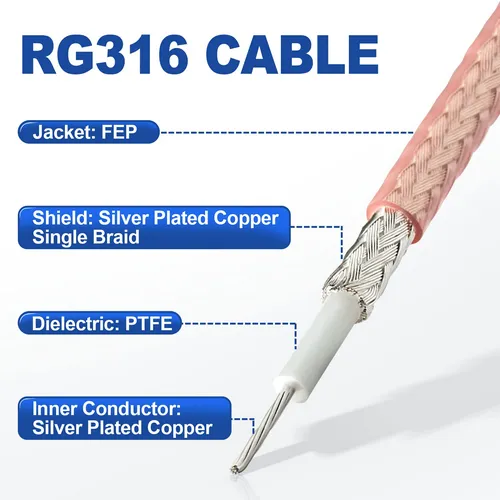

This figure details the construction of RG316 cable, including the silver-plated copper inner conductor, PTFE insulation, FEP jacket, and braided shield. It is referenced in the context of using short jumpers for vibration absorption and low attenuation in outdoor setups.

Conductor, dielectric, braid, and jacket — explained without marketing noise

A typical RG316 coaxial cable uses:

- A silver-plated copper center conductor, chosen for stable RF performance and corrosion resistance

- A PTFE dielectric, which holds impedance well across temperature and frequency

- A silver-plated copper braid, providing adequate shielding for dense RF layouts

- An FEP outer jacket, enabling flexibility and high-temperature tolerance

This construction is why RG316 is popular inside enclosures. It tolerates heat better than PVC-jacket micro-coax and routes cleanly without excessive stiffness.

Specs that actually influence design decisions

In practice, three specifications matter far more than the rest:

- Characteristic impedance (50 Ω) — compatibility with radios, filters, and antennas

- Attenuation vs frequency — the real limiter on usable length

- Mechanical flexibility — how easily the cable survives routing and rework

Velocity factor, dielectric constant, and silver thickness matter mainly in edge cases such as phase-matched paths or tightly synchronized antenna arrays.

How to read RG316 datasheets without getting lost

When comparing suppliers, engineers often overanalyze small differences in published attenuation numbers. For short RG316 jumpers, those differences are usually secondary to:

- Connector quality

- Assembly consistency

- Bend radius control

Two RG316 cables with similar construction will behave nearly the same electrically over short distances. The larger variation tends to come from how they’re terminated and routed, not the cable core itself.

For a deeper, measurement-oriented look at RG316 construction and test data, you can reference a focused breakdown like RG316 Coaxial Cable Guide: Specs, Loss & Use .

How does RG316 compare against RG174, RG58, and LMR-200 in real projects?

Size, bend radius, and routing — what you notice immediately

- RG316 is thin, flexible, and forgiving in tight spaces

- RG174 is similar in size but slightly less robust at temperature extremes

- RG58 is noticeably thicker and stiffer, though still hand-routable

- LMR-200 demands planning; sharp bends and crowded enclosures become issues

Attenuation and power trends across common bands

Loss differences that look small at 433 MHz become decisive at 5.8 GHz. Typical patterns engineers observe:

- At sub-GHz, RG316 loss is usually acceptable even up to ~1 m

- At 2.4 GHz, RG316 works well for short internal jumpers

- At 5–6 GHz, RG316 length must be tightly controlled

This is where RG58 or LMR-200 often outperform RG316, even when slightly longer.

When thicker cable beats a shorter RG316 run

A common surprise in Wi-Fi and 5G prototypes is discovering that:

A moderately longer run of LMR-200 can lose less signal than a short RG316 jumper at high frequency.

That doesn’t mean RG316 is “bad.” It means its role is mechanical convenience first, electrical efficiency second.

A quick comparison snapshot engineers actually use

| Constraint | Best choice |

|---|---|

| Space-limited | RG316 |

| Loss-limited | LMR-200 |

| Cost-sensitive | RG58 |

| Frequent rework | RG316 / RG174 |

How do you design RG316 coax jumpers with the right connectors and orientations?

Matching connector types to real devices

This is a close-up photo or schematic showing one end of an RG316 cable terminated with a Fakra connector (typically color-coded, e.g., blue, green). Fakra is a standardized series of RF connectors commonly used in automotive and telematics applications. This image is used to illustrate the versatility of RG316 cable—it is electrically neutral but can be adapted to various device ports through different connector terminations. Appearing in the section discussing “Matching connector types to real devices,” this diagram aims to remind engineers that RG316 assemblies can be compatible with various connector standards including Fakra, and selecting the correct connector is crucial for ensuring both mechanical compatibility and electrical performance.

This is a composite photo or schematic showing multiple RG316 jumpers, each with different connector combinations on both ends. The image might include common pairings such as: SMA Male to SMA Female, RP-SMA Male to RP-SMA Female, BNC to N-type, MCX to SMA, etc.

RG316 assemblies commonly terminate in:

- SMA and RP-SMA for Wi-Fi, IoT, and embedded radios

- BNC or N-type for test equipment and legacy systems

- MCX / MMCX / SMB / SMP for compact RF modules

- Fakra in automotive and telematics applications

The cable itself is electrically indifferent. The device port is not.

Straight vs right-angle — it’s about strain, not aesthetics

Right-angle connectors save space but concentrate mechanical stress near the termination. Straight connectors route more cleanly when clearance allows.

A common pattern inside enclosures is mixing the two: straight at the bulkhead, right-angle at the module, or vice versa, depending on mounting geometry.

Gender and polarity traps that still catch teams

SMA vs RP-SMA confusion remains one of the most frequent RG316 ordering mistakes. Threads mate. Pins don’t.

Experienced engineers verify center pin vs socket, not just male/female labels. This habit alone eliminates a large class of silent failures.

If your system spans multiple antenna products, cross-checking with practical examples like [WiFi antenna extension examples using RG316 jumpers] can help align connector conventions early.

Color-coding and labeling aren’t cosmetic

How do you control bend radius, routing, and strain relief for RG316 inside tight hardware?

Bend radius: what teams actually use, not just what datasheets say

Most datasheets publish a minimum bend radius. In practice, engineers rarely design right at that limit—especially for permanent routing.

A rule that shows up again and again in real hardware:

For fixed routing, keep bends at least 10× the cable diameter.

This isn’t about immediate failure. Tighter bends slowly deform the dielectric and braid. At sub-GHz you may never notice. At 2.4 GHz and above, the effect starts to show up as extra loss or unstable return loss during temperature changes.

Temporary bends during assembly are usually fine. Permanent tight bends are where trouble accumulates.

Strain relief: support the cable, don’t trap it

Inside enclosures, RG316 should be guided and supported, not locked in place aggressively.

What generally works well:

- Gentle loops near connectors so movement isn’t transferred directly to the crimp

- Soft clips or adhesive mounts spaced along longer runs

- Leaving a little slack instead of pulling the cable taut

What causes problems:

- Hard zip ties tightened near the connector ferrule

- Pinching the cable between PCB edges and enclosure walls

- Using the cable itself as a structural element

Crushing the braid rarely causes an obvious failure. Instead, it degrades shielding and impedance subtly. Those are the bugs that waste the most time later.

Routing multiple RG316 jumpers together

In multi-radio designs, it’s common to see several RG316 jumpers sharing the same space. When they run parallel for long distances, coupling becomes more noticeable—especially above 2.4 GHz.

If separation isn’t possible, crossing cables at shallow angles or staggering their paths slightly helps. These small layout choices often make VNA plots look calmer, even if nothing else changed.

How should you size RG316 coax cable for power, temperature, and reliability margins?

Continuous RF power vs short bursts

RG316 handles modest RF power comfortably when duty cycle is low. Problems show up when power is continuous and frequency is high.

As frequency increases, attenuation increases. That loss turns into heat along the cable length, not just at the connectors. In compact enclosures, there’s often nowhere for that heat to go.

Enclosure temperature matters more than many expect

A jumper that feels fine on an open bench can behave very differently once sealed inside a small metal box. Elevated ambient temperature reduces margin quickly.

Many experienced teams apply simple derating rules instead of chasing precise limits:

- 30–50% power derating for 24/7 operation

- Extra caution above 2.4 GHz, even for short runs

This approach isn’t pessimistic. It’s how teams avoid “it passed validation but failed in the field” situations.

Realistic reliability expectations

In static installations with little movement, RG316 jumpers can last many years. In systems with vibration, flexing, or frequent reconnection, service life shortens fast.

In lab racks and test fixtures, some engineers schedule proactive replacement every 2–3 years. That policy usually comes after one painful intermittent failure—not before.

What industry trends are pushing more micro-coax jumpers like RG316 into new designs?

Denser RF layouts are the new normal

Automotive and embedded systems are adopting similar constraints

Miniaturization keeps favoring predictable, flexible cables

Wearables, medical devices, and small industrial modules all reward cables that are easy to route and tolerant of assembly variation. RG316 fits that role—as long as its limits are respected.

The trend isn’t “RG316 everywhere.” It’s smaller radios forcing better planning discipline.

How do you turn engineering requirements into a clean RG316 cable assembly order?

Minimum fields every RG316 order should include

At a bare minimum, a clean order or internal spec should spell out:

- Cable type: RG316 coax cable

- Operating frequency or band

- Finished length (with tolerance)

- Connector A and Connector B

- Orientation (straight or right-angle)

- Jacket or boot color

If any of these are implied instead of written down, mistakes creep in.

Details that save time later

For production builds or customer-facing products, adding a few more fields usually pays off:

- Test or inspection requirements

- Labeling or serialization

- Packaging expectations

These don’t change RF performance, but they dramatically reduce rework and miscommunication.

Standardizing RG316 jumpers internally

Many teams eventually define a small set of “house” RG316 jumpers for labs and product lines. That consistency speeds debugging and makes measurements easier to compare over time.

Linking those internal standards back to broader references—such as the RG Cable Guide—also helps new engineers understand why those choices were made.

Which practical RG316 coax cable questions still confuse teams?

Is RG316 coax cable too lossy for a 6 GHz Wi-Fi jumper under 0.5 m?

Can RG316 and RG58 be mixed in the same RF path?

Does jacket color change RG316 performance?

What’s a realistic service life for RG316 jumpers in 24/7 setups?

Factory-terminated or in-house crimped assemblies?

Can RG316 be used to carry DC or PoE?

Closing perspective

RG316 coax cable jumpers aren’t a shortcut and they aren’t a liability. They’re a precise tool for short, space-constrained RF paths.

Most complaints about RG316 being “too lossy” trace back to skipped planning steps rather than the cable itself. Treat RG316 as part of the RF system—not as an afterthought—and it behaves predictably.

When everything else is done right, the best RG316 jumper is the one you stop thinking about.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.