SMA Extension Cable: Length Limits, Matching & Panel Mounting

Jan 8,2025

Preface

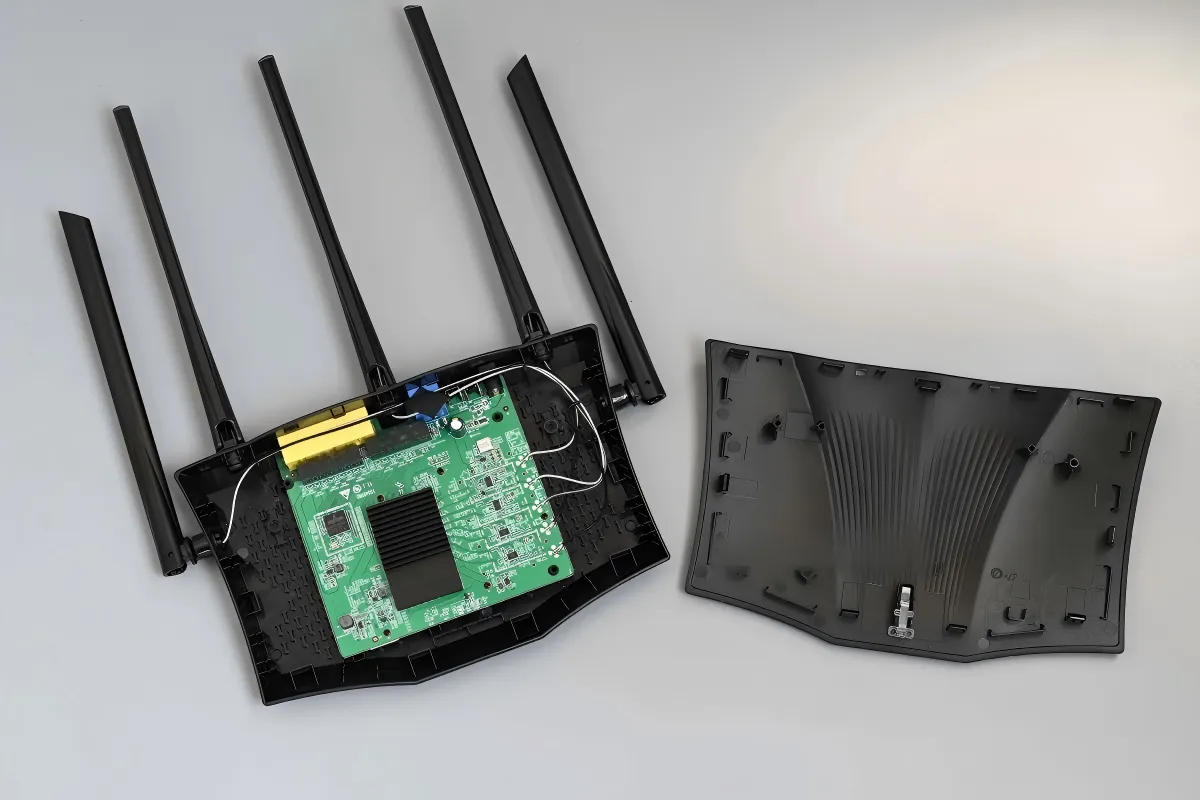

This is a schematic or photo of a typical coaxial extension cable with SMA connectors, placed near the “Preface” section of the article. It visually presents the core subject of discussion and implies that this passive component, often considered late in the design cycle, though small, has a decisive impact on the performance margin of high-frequency (5GHz/6GHz) Wi-Fi links. Its purpose is to concretize the abstract concept of an “extension cable” and establish a visual foundation for the subsequent in-depth discussion of practical issues such as its length limits, interface matching, and mechanical installation.

An SMA extension cable rarely appears on a design risk checklist. It’s passive, inexpensive, and usually added late—often after the radio, antenna, and enclosure already feel settled. That timing is exactly why it causes trouble in real deployments.

At 2.4 GHz, systems tend to be forgiving. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, they are not. A few extra centimeters of coax, one unnecessary adapter, or a misidentified connector interface can quietly erode the link margin. Nothing fails outright. The device powers up, RSSI looks acceptable, and basic connectivity works. Then throughput drops first. Higher MCS rates refuse to hold. Coverage becomes inconsistent.

Most of these issues don’t come from misunderstood RF theory. They come from small assumptions made late in the build, especially around SMA vs RP-SMA identification, extension length choices, and panel feed-through details. This guide focuses on those decisions—the ones that rarely look risky on paper but routinely surface as field problems months later.

How do I confirm SMA vs RP-SMA before ordering an extension?

Thread × pin/hole quick ID (device vs antenna)

Figure is the core of the document’s “error-proofing guide.” It addresses a long-standing and costly pain point in RF connectivity. The image not only shows the difference but also teaches through clear visual labels (e.g., “RP-SMA”, “SMA”). Understanding this distinction is crucial for correctly connecting consumer Wi-Fi gear (often using RP-SMA) with standard RF test instruments (often using SMA). This figure is a must-know visual tool for engineers and procurement personnel.

| Interface | External Thread | Center Contact |

|---|---|---|

| SMA Male | Yes | Pin |

| SMA Female | No | Socket |

| RP-SMA Male | Yes | Socket |

| RP-SMA Female | No | Pin |

There are two practical rules worth remembering. First, always inspect the device port and the antenna separately; they are often different. Second, do not assume that “male” or “female” in a product title refers to the RF interface—it frequently describes only the thread.

Most consumer routers and access points ship with RP-SMA-Female ports on the chassis, even though the antennas themselves may look identical to standard SMA at a glance. For background context on how this interface family evolved and why reverse-polarity variants exist, the overview on SMA connector fundamentals remains a neutral technical reference.

Why “it screws on but underperforms” happens

This is the most misleading failure mode. A mismatched SMA connector and RP-SMA connector can often be joined mechanically using adapters or hybrid jumpers. Everything feels normal during assembly. Electrically, the connection is compromised.

What actually changes is subtle. The center contact geometry no longer mates as intended, contact pressure becomes inconsistent, and return loss increases—especially above 5 GHz. Each small impedance discontinuity reflects a bit of energy back toward the radio. Individually, these reflections seem insignificant. Together, they add up.

The result is not a hard failure but degraded performance: unstable throughput, sensitivity to orientation, or links that collapse only at higher data rates. This is why rp-sma vs sma mistakes so often present as “mysterious RF issues” rather than obvious assembly errors. When a system works at low rates but struggles under load, connector end-type mismatch is one of the first things worth re-checking.

When is an SMA extension cable necessary—and when is a shorter chain better?

An SMA extension cable isn’t inherently bad. It’s just frequently used when it shouldn’t be.

In practice, the question is not whether an extension “works,” but whether it is the cleanest way to solve the physical problem in front of you.

Wall, rack, and outdoor runs: necessity versus alternatives

An extension cable is usually justified when antenna placement is constrained by mechanics rather than RF preference. Typical examples include wall-mounted access points, rack-installed radios, and outdoor enclosures where the antenna must exit a metal housing. In these cases, the extension is not optional—it is part of the mechanical design.

Panel feed-throughs, weather sealing, and clearance from metal surfaces often force the RF port several centimeters away from the antenna mounting point. Here, a short sma extension cable combined with a bulkhead connector is the most stable solution, especially when vibration or servicing access is involved.

Where problems begin is when extensions are added for convenience rather than necessity. A cable added “just in case” often stays forever, quietly consuming link margin.

When an internal jumper is the cleaner solution

This schematic, through comparison or a single scenario depiction, illustrates the inside of a typical equipment chassis. It might show that the antenna mounting point and the device RF port are relatively close but separated by a spatial obstacle. One solution is to use a longer SMA extension cable that goes around, while the other is to use a short SMA male-to-female jumper for a direct connection. This image supports a key argument in the text: when the antenna only needs to move a small distance inside the chassis, reducing the number of interfaces and using a direct short jumper provides a cleaner RF path, fewer impedance discontinuities, and greater stability, especially at 5GHz and above. This is an effective yet often overlooked method for solving many stability issues mistakenly attributed to antennas or RF chips.

If the antenna only needs to move slightly inside the enclosure, a long extension is rarely the best answer. A short sma antenna cable or a single sma male to female jumper usually produces a cleaner RF path.

From a field perspective, fewer interfaces almost always win. One jumper introduces one controlled impedance transition. An extension plus two adapters introduces three. At 5 GHz and above, that difference is no longer theoretical.

Many stability issues attributed to antennas or radios are resolved simply by replacing a long internal extension with a shorter, direct jumper. It’s one of the easiest fixes—and one of the most overlooked.

How long can I go at 5 GHz or 6 GHz before throughput drops?

Connector and adapter stacking penalties

Every connector interface introduces loss and reflection. In field measurements and production tuning, a practical rule of thumb still holds: each additional connector or adapter costs roughly 0.2 dB at 5–6 GHz. That loss compounds quickly when adapters are stacked back-to-back.

The important point is not the exact number but the pattern. One adapter is manageable. Three adapters plus a long cable often push the link into marginal territory, especially for high MCS operation.

This is why shortening the chain and eliminating interfaces is often more effective than switching antennas.

Length–Loss Quick Estimator

This estimator is not a simulation. It is a deployment-level sanity check designed to prevent overextension.

Inputs

- Frequency: 2.4 GHz / 5 GHz / 6 GHz

- Cable type: RG178 (example baseline)

- Cable length L (meters)

- Number of intermediate connectors or adapters n

Estimator

Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

Typical real-world attenuation values for RG178 are shown below. These numbers are rounded and intentionally conservative.

| Frequency | Approx. Attenuation α (dB/m) |

|---|---|

| 2.4 GHz | ~ 1.5 |

| 5 GHz | ~ 2.3 |

| 6 GHz | ~ 2.8 |

| Length Tier | Expected Impact at 5/6 GHz | Action Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.1 m | Negligible | Safe default |

| 0.3 m | Minor | Preferred when possible |

| 0.5 m | Noticeable | Acceptable with margin |

| 1 m | Clear throughput loss | Switch to lower-loss cable |

| 2 m | Severe degradation | Redesign the RF path |

This applies directly to wifi antenna extension cable deployments where the extension sits outside the enclosure and must tolerate environmental exposure. At these lengths, cable choice and connector count matter as much as antenna gain.

A common field mistake is compensating for extension loss with a “higher-gain” antenna. That approach often increases pattern distortion and regulatory risk without solving the underlying loss budget problem.

How should both ends be paired so it works the first time?

This image likely uses a link performance curve or symbolic signal attenuation diagram to visualize the “silent” performance degradation caused by incorrect SMA vs. RP-SMA pairing (even if mechanically connectable). It might compare the performance of a correctly paired link (stable high throughput) with an incorrectly paired one (fluctuating throughput, unstable high MCS rates). This diagram visually explains the failure mode described in the text: no smoke or obvious faults, the device powers up, basic connectivity works, but performance never quite meets expectations, especially at high data rates and under load. Such problems are often categorized as “mysterious RF issues” during field troubleshooting, with the root cause often being interface type mismatch.

Connector pairing errors rarely announce themselves. There’s no smoke, no obvious fault, and usually no immediate failure. Everything powers up, the link comes online, and basic connectivity looks fine. The trouble is that performance never quite matches expectations.

In field troubleshooting, many unstable links traced back to SMA extension cable chains start with this exact issue.

Router and access point reality: RP-SMA is the default

On most routers and access points, the device side still ships with RP-SMA-Female ports, paired with RP-SMA-Male antennas. This has been standard for years, yet it’s easy to miss because RP-SMA looks almost identical to standard SMA at a glance.

Problems begin once adapters are added to “make it fit.” The connection may feel solid, but electrically it’s rarely optimal. If a router uses RP-SMA, the most stable approach is to keep the entire external chain RP-SMA end to end rather than mixing formats. This avoids unnecessary transitions and keeps return loss predictable.

Industrial and IoT equipment: consistency beats convenience

Industrial radios and IoT gateways are more likely to use SMA-Female connectors on the device with SMA-Male antennas. Where issues appear is during hardware revisions—new enclosures, reused antennas, or last-minute mechanical changes that introduce adapters into the path.

Adapters often start as temporary fixes and quietly become permanent. In practice, changing the cable to the correct interface is usually cleaner than stacking adapters. A single, correctly specified jumper is easier to control, document, and maintain than a chain of transitions.

When cross-type pairing can’t be avoided

There are cases where mixed interfaces are unavoidable: certified antennas, legacy equipment, or mechanical constraints that can’t be changed. In those situations, the trade-off should be explicit.

Each adapter adds loss and reflection, and those penalties become more visible as frequency increases. At 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, shortening the cable and reducing transitions often recovers more margin than any adapter-based workaround. For background on how antenna interfaces influence radiation and matching, general references such as radio antenna fundamentals help explain why small discontinuities matter more at higher frequencies.

How do I spec an SMA bulkhead so it doesn’t come back for rework?

The stack-up detail most people underestimate

A common mistake is selecting an SMA bulkhead based only on panel thickness. In reality, usable thread length must account for the full stack-up: panel, washer, O-ring after compression, nut engagement, and a small allowance for assembly tolerance.

If the thread is too short, the seal never compresses correctly and environmental protection fails. If it’s too long, torque control becomes inconsistent or the connector bottoms out before it’s secure. Neither problem shows up immediately, which is why they tend to surface only after deployment.

Single-nut versus flange styles in real environments

Single-nut bulkheads work well for thin panels and low-vibration indoor equipment. Once vibration, shock, or outdoor exposure enters the picture, flange-mounted bulkheads become more reliable.

Two-hole and four-hole flange designs resist rotation and distribute stress across the panel, which is why they’re commonly used in industrial cabinets and outdoor radios. In these cases, pairing the bulkhead with a sealing or protective cap is no longer optional—it’s part of a robust installation.

How should the cable be routed inside the chassis?

Bend radius, strain relief, and edge clearance

A conservative rule that holds up well in the field is maintaining a bend radius of at least ten times the cable’s outer diameter. Tighter bends may pass initial testing but tend to fail after vibration or thermal cycling.

Sharp metal edges are another slow failure mechanism. Even without visible abrasion, repeated micro-movement against an edge degrades the jacket over time. Simple measures such as edge clearance, grommets, or adhesive tie-downs near connectors significantly reduce these risks.

Why one jumper is better than stacked adapters

This is a clear physical photograph showing a short jumper cable with an SMA male connector on one end and an SMA female connector on the other. The image might place it against a plain background to highlight its structure. This picture directly corresponds to the discussion in the text about “why one jumper is better than stacked adapters.” It provides a concrete, actionable visual reference for the solution: when internal device connections or direction changes are needed, this single jumper should be preferred over using two back-to-back adapters plus a cable. This approach significantly reduces the number of mated interfaces, thereby lowering insertion loss, improving impedance consistency, and enhancing mechanical reliability.

This is a physical photograph of a standalone SMA male-to-female adapter

Two back-to-back adapters often look harmless. Electrically and mechanically, they are not. Each adapter adds another interface, another tolerance stack, and another reflection point.

Replacing that stack with a single SMA male-to-female jumper simplifies the chain immediately. Fewer interfaces, cleaner impedance, and less mechanical play. In many deployments, this single change stabilizes links that previously behaved inconsistently.

What needs to be on the PO so the order doesn’t get rejected?

SMA extension cable PO checklist

| Item | Must be specified |

|---|---|

| Interface type | SMA or RP-SMA |

| Center contact | Pin or socket |

| End configuration | M-F, M-M, or F-F |

| Cable type | RG178, RG316, etc. |

| Length | 0.1-2 m |

| Bulkhead or flange | Yes / No (and hole pattern if applicable) |

| Sealing cap | Yes / No |

| Quantity | Required |

A short, explicit note usually avoids follow-up entirely.

Example:

RP-SMA-M to RP-SMA-F, RG178, 0.3 m, single-nut bulkhead, sealing cap included, quantity 50.

That level of clarity keeps procurement, warehousing, and assembly aligned without unnecessary back-and-forth.

Why recent Wi-Fi deployments tolerate even less margin than before

As Wi-Fi systems move toward higher modulation schemes and 6 GHz operation, the tolerance for extra loss continues to shrink. Extensions that once felt “short enough” can now be the difference between stable throughput and intermittent performance.

At the same time, enclosures are getting smaller and denser, pushing radios deeper into metal housings. That shift makes RF paths less forgiving and places more importance on deliberate, minimal-loss extension chains rather than flexible but lossy routing.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.