WiFi Antenna Cable: Extension Length, Loss & End-Type Pairing

Jan 7,2025

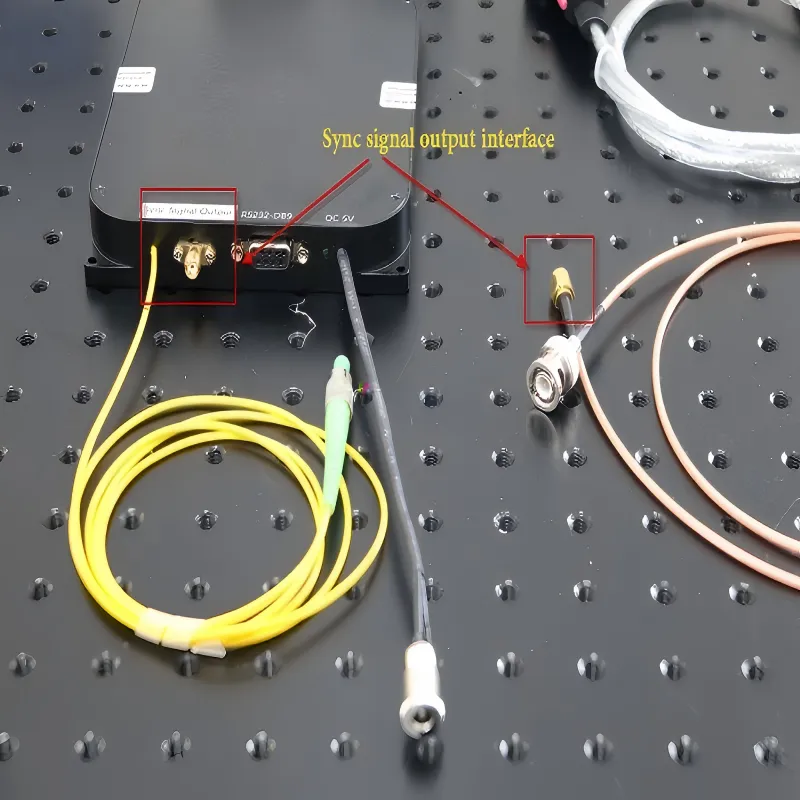

This is typically a simple schematic or photo of a flexible coaxial cable terminated with SMA connectors, placed below the main article title. It visually represents the core theme of “Wi-Fi antenna cable,” aiming to establish an intuitive impression for the reader from the outset and hinting that this passive component, often considered late in the design cycle, is actually a key variable determining link performance (such as throughput and stability) in the 5GHz and 6GHz bands.

A wifi antenna cable rarely feels like a decision that deserves serious discussion. It is passive, inexpensive, and almost always added late in the design cycle—after the radio module is chosen, the enclosure is finalized, and the antenna location already looks “good enough.” That timing is precisely why antenna cable problems tend to surface only after deployment rather than during early testing.

At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, Wi-Fi systems rarely fail in obvious ways. Instead, they degrade quietly. Throughput drops before coverage disappears. Higher MCS rates become unstable long before the link is lost. In many real deployments, the antenna itself is blamed first, followed by the chipset or firmware. Only later does it become clear that the issue lives in the cable and connector layer that was treated as an afterthought.

This guide focuses on practical field decisions rather than RF theory. We will look at how to confirm SMA vs RP-SMA before ordering, when a wifi antenna extension cable is genuinely useful, and how extension length and connector count interact at higher frequencies where margins are thin.

How do I quickly confirm whether my device port is SMA or RP-SMA before ordering?

This chart is the core tool for avoiding ordering mistakes. It presents the two decisive physical characteristics of a connector (thread location, center contact type) in a 2x2 matrix, defining the four connector types. The chart typically includes simple line drawings or silhouettes to show the appearance of each type. This diagram directly corresponds to the “four-quadrant quick identification method” described in the text, emphasizing that identification must be based on the physical interface itself (threads and contacts), not on labels or the illusion that “it looks like it screws on.” This is the first step in preventing electrical performance degradation due to SMA/RP-SMA confusion.

Most ordering mistakes are not caused by a lack of RF knowledge. They are caused by visual assumptions. SMA and RP-SMA connectors look similar enough that even experienced engineers occasionally rely on habit instead of geometry, especially when inspecting a device already mounted in an enclosure.

Threads alone are misleading. Both SMA and RP-SMA may use external threads, and both may tighten cleanly. The correct identification comes from separating appearance from definition and focusing on the physical interface itself rather than the label printed on a datasheet.

Thread × pin/hole: the four-quadrant quick identification method

Any SMA-family connector can be identified reliably by answering two questions. First, where are the threads—on the outside of the connector or on the inside? Second, what is the center conductor—a solid pin or a socket (hole)? Those two observations uniquely define whether the interface is SMA or RP-SMA.

The critical point is simple but often missed: SMA vs RP-SMA is defined by the center conductor, not by the threads. External threads do not automatically mean “SMA male,” and internal threads do not automatically mean “RP-SMA female.” Once the pin or socket is confirmed, the designation becomes unambiguous.

If you want a deeper, order-oriented explanation of how these combinations map to real routers and antennas, the practical breakdown in RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching & Ordering walks through the same logic from a procurement and field-inspection perspective.

Why “it screws on but underperforms” happens

One reason SMA/RP-SMA mistakes persist is that they do not always cause immediate failure. A mismatched connection may tighten fully and even pass a basic continuity check. Electrically, however, the center conductors may be barely touching or making inconsistent contact, especially under vibration or temperature changes.

The result is a combination of elevated return loss and unstable impedance at the connector interface. At 2.4 GHz, this may remain hidden during casual testing. At 5 GHz and above, it usually appears as unstable throughput at higher data rates rather than a complete link drop. This is why connector misidentification often slips through lab testing and only becomes obvious after installation.

Should I use a wifi antenna extension cable, and when does it actually make sense?

This schematic clearly shows, through side-by-side or top-bottom comparison, two common yet easily confused pairing conventions: 1) Consumer/Enterprise Router Convention: Device port is RP-SMA female (RP-SMA-F), antenna is RP-SMA male (RP-SMA-M). 2) Industrial/IoT Device Convention: Device port is SMA female (SMA-F), antenna is SMA male (SMA-M). This diagram aims to correct engineers’ potential subconscious assumption that “RP-SMA is everywhere,” clearly pointing out that different product categories follow different connector conventions, and incorrect pairing will lead to unnecessary returns and compatibility issues.

A wifi antenna extension cable solves a mechanical placement problem, not an RF one. It allows the antenna to be positioned where it radiates more effectively, but it does so at the cost of predictable insertion loss. Whether that trade-off makes sense depends entirely on the deployment context.

In home and enterprise access points, short extension cables are commonly used to move antennas away from metal enclosures, improve spatial diversity, or clear obstructions caused by wall or ceiling mounts. In these scenarios, extensions in the 0.1–0.5 m range often produce a net benefit because better antenna placement outweighs the added cable loss.

Industrial gateways operate under different constraints. DIN-rail cabinets, sealed housings, and outdoor enclosures frequently require antennas to exit the chassis entirely. In these cases, the extension cable is not optional—it is part of the mechanical design. Here, connector robustness, sealing strategy, and strain relief often matter more than shaving a few centimeters off the cable length.

For a broader view of how common coaxial cables behave as frequency increases, the overview in the RG Cable Guide provides useful context when deciding whether a longer extension or a different cable type is the better choice.

When switching to a shorter run or an internal SMA antenna cable is better

There is a point where adding length stops helping. If an extension exists only to compensate for late enclosure changes, it is often worth reconsidering the layout instead. Replacing multiple adapters with a single short sma antenna cable, rotating the radio module, or relocating the antenna feed-through can recover margin more effectively than upgrading to a “better” extension.

In practice, many unexplained range regressions disappear once unnecessary extensions and adapters are removed rather than optimized.

How far can I extend at 5/6 GHz before throughput drops?

At higher Wi-Fi bands, cable length alone rarely tells the full story. Connector count and transition quality matter just as much as meters of coax, and in compact systems they often matter more. Every additional interface introduces insertion loss, but more importantly, it introduces another opportunity for small impedance discontinuities that only show up once data rates climb.

In practical Wi-Fi hardware, especially at 5 GHz and 6 GHz, these effects compound quietly. A setup may look perfectly stable during low-rate testing and still struggle once higher MCS levels are negotiated. This is why field issues are frequently misattributed to antennas or firmware when the real bottleneck sits in the interconnect chain.

A commonly used planning estimate assigns approximately 0.2 dB of loss per connector or adapter under reasonable assembly conditions. This assumes typical SMA-family connectors, proper torque, and clean mating surfaces—conditions that are common in production but not guaranteed in reworked or prototype builds. When adapters are stacked back-to-back inside a chassis, that loss accumulates faster than many engineers expect.

Length–loss quick estimator

This estimator is intended as a field-level planning tool, not a lab-grade model. It reflects what engineers typically see when working with miniature Wi-Fi coax assemblies rather than idealized transmission lines.

Inputs:

Operating frequency (2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz), cable type (for example, RG178), cable length L in meters, and the number of intermediate connectors or adapters n.

Estimator:

Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

This rule of thumb assumes commonly used low-loss miniature coax (such as RG178 or similar), properly terminated SMA-family connectors, and typical Wi-Fi output power levels found in access points and gateways. It also assumes normal indoor routing, not extreme bend radii or mechanically stressed assemblies.

Outputs:

Recommended length tier (0.1 / 0.3 / 0.5 / 1 / 2 m), expected throughput impact (minor, noticeable, or significant), and a suggested action such as shortening the run, reducing adapters, or switching to a lower-loss cable.

In real deployments, removing a single unnecessary adapter often delivers the same improvement as cutting several tens of centimeters from the cable—without touching the routing at all. This is one reason experienced teams tend to focus on interface count first, and cable length second, when troubleshooting marginal links at 6 GHz.

How do I pair both ends correctly the first time, and which combinations minimize rework?

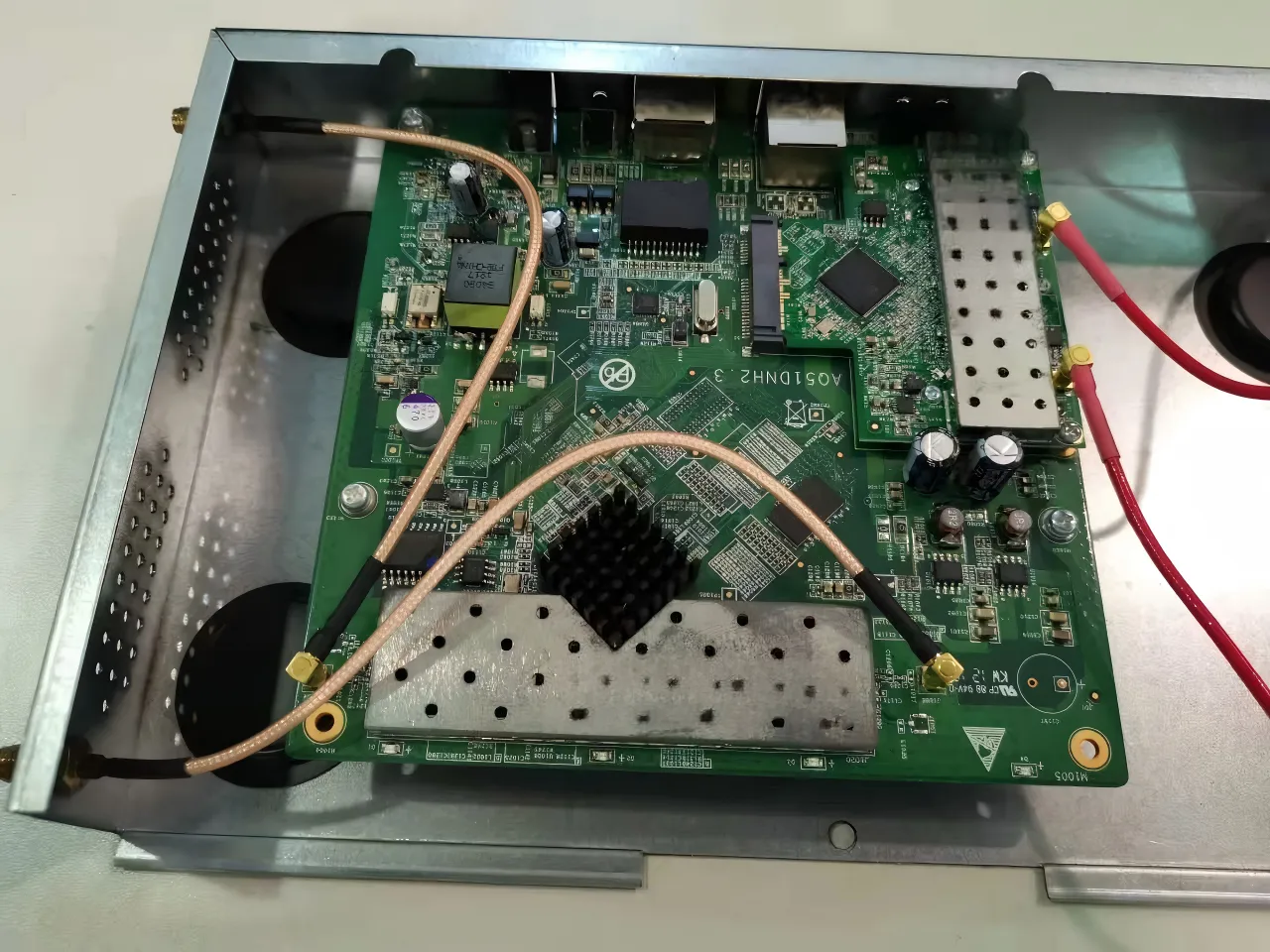

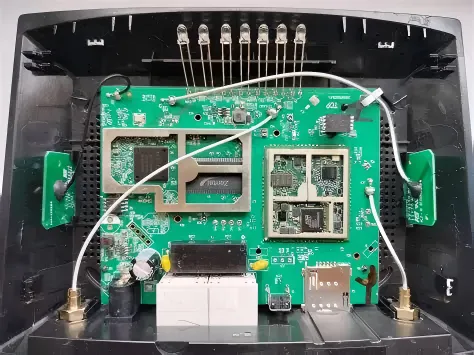

This schematic focuses on the inside of a device chassis, visualizing several key internal routing guidelines through correct/incorrect comparisons or annotations of best practices. Key points include: maintaining a generous bend radius (often annotated as ≥10x cable outer diameter), avoiding proximity to sharp edges of the chassis, and placing strain relief points (e.g., cable ties, clips) before the connector (not directly at it). This diagram corresponds to the discussion on internal jumper routing in the text, emphasizing that improper routing does not cause immediate failure but leads to slow performance drift and reliability degradation through long-term mechanical stress (e.g., shield deformation, dielectric fatigue), which is a common but subtle root cause of problems in field deployments.

Once the port type is confirmed, the next failure point is end-to-end pairing. This is where many otherwise correct orders still go wrong. The issue is rarely that engineers do not know the rules; it is that assumptions from one product category quietly leak into another.

Consumer routers, enterprise access points, and industrial gateways do not follow the same connector conventions. Mixing those mental models is a reliable way to create avoidable returns.

Common home and enterprise routers: RP-SMA-F on the device to RP-SMA-M on the antenna

Most consumer and light enterprise Wi-Fi equipment ships with RP-SMA female jacks on the device. The matching external antenna therefore uses RP-SMA male. This pairing has become the de facto standard in that market, largely to discourage users from attaching unintended high-gain antennas without realizing it.

Because this convention is so widespread, many engineers subconsciously assume RP-SMA everywhere. That assumption holds until the first industrial gateway or embedded radio appears in the design, at which point the mental shortcut breaks down.

Industrial and IoT devices: SMA-F on the device to SMA-M on the antenna

Industrial radios and IoT gateways more commonly use SMA female connectors on the device side, paired with SMA male antennas. The reasons are practical rather than theoretical: SMA is mechanically robust, well standardized, and widely supported across industrial antenna ecosystems.

This difference is why mixed deployments—such as a consumer router feeding an industrial enclosure—often experience pairing confusion. A clean way to avoid this is to document the expected connector family explicitly in the BOM rather than relying on tribal knowledge.

For a focused comparison of where these conventions come from and how to spot them quickly in the field, the ordering notes in RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching & Ordering are useful as a cross-check during procurement.

Adapters, compliance, and EIRP trade-offs

Adapters are often treated as harmless conveniences. Electrically, they are not free. Every adapter adds insertion loss, increases the chance of impedance mismatch, and slightly complicates regulatory calculations tied to EIRP.

In regulated environments, especially outdoors, adapter-induced loss can push a system closer to compliance limits in unexpected ways. While loss technically reduces radiated power, it also alters antenna efficiency and pattern assumptions used during certification.

When cross-family pairing is unavoidable, a single integrated jumper cable is almost always preferable to stacking multiple adapters. It reduces loss, improves mechanical reliability, and simplifies documentation.

How do I spec an SMA bulkhead hole size and thread length for panel feed-throughs?

Stack-up math that actually works in the field

A reliable bulkhead installation starts by accounting for the full stack height, not just the panel thickness. In practice, the required thread length must accommodate the panel, any flat washer, the compressed O-ring, sufficient nut engagement, and a small assembly margin.

Ignoring any one of these elements leads to familiar symptoms: connectors that bottom out before sealing, O-rings that never compress properly, or nuts that barely catch a thread. These issues often survive bench inspection and fail later under vibration or temperature cycling.

A more detailed discussion of thread length options, sealing behavior, and practical tolerances is covered in SMA Bulkhead: Panel Hole Size, Thread Length & Sealing, which focuses specifically on avoiding these late-stage surprises.

Single-nut versus flange mounts: anti-rotation and vibration considerations

Single-nut bulkhead connectors are fast to install and perfectly adequate for low-vibration environments. However, in mobile or industrial installations, rotation and loosening become real risks over time.

Two-hole and four-hole flange mounts trade installation speed for stability. They provide built-in anti-rotation and distribute mechanical stress more evenly across the panel. In practice, flange mounts are often the safer choice when downtime or service access is limited.

The key is to treat the bulkhead not as a connector choice, but as a mechanical interface that must survive the same environmental conditions as the rest of the enclosure.

How should I route internal jumpers so the coax is not stressed over time?

By comparing correct and incorrect routing methods, this diagram visualizes several key internal routing guidelines: maintaining a generous bend radius (typically ≥10x cable OD), placing strain relief points before the connector, and avoiding tight contact with metal walls to maintain consistent impedance and reduce unpredictable ground paths. It emphasizes that seemingly neat assemblies can hide long-term reliability risks (e.g., fatigue, impedance mismatch), and good internal routing is fundamental to ensuring the cable’s long-term stable operation under vibration and temperature cycling.

Bend radius, edge clearance, and strain relief placement

A conservative and widely accepted guideline is to maintain a minimum bend radius of at least ten times the cable’s outer diameter. This reduces mechanical stress on the dielectric and minimizes long-term impedance changes.

Sharp edges are another common problem. Routing coax along stamped metal or near enclosure cutouts without sufficient clearance can damage the jacket over time. Adding simple strain relief near the connector and avoiding tight tie-downs near the termination significantly improves durability.

When an SMA male-to-female jumper beats stacked adapters

Inside a chassis, it is tempting to solve orientation or reach issues with back-to-back adapters. Electrically and mechanically, this is almost always inferior to using a short sma male to female cable.

A single jumper reduces interface count, lowers insertion loss, and removes a rigid mechanical joint that can loosen under vibration. In compact enclosures, this small change often improves both RF performance and long-term reliability with no layout penalty.

What belongs on my PO so warehousing will not bounce it?

Procurement failures are rarely technical. They are informational. A warehouse cannot guess intent, and ambiguous orders tend to be paused, questioned, or shipped incorrectly.

A clear purchase order eliminates most of these issues before they start.

PO checklist that prevents back-and-forth

A complete PO for a wifi antenna cable or extension assembly should explicitly list connector family (SMA or RP-SMA), center contact gender (pin or socket), end configuration (M–F or M–M), cable type (for example, RG178), and exact length. If a bulkhead or flange is required, that should be stated clearly, along with any sealing accessories such as O-rings or caps.

Writing these details once is faster than answering clarification emails later. Many teams standardize this information after a few painful lessons.

This same discipline is recommended in the ordering examples shown in the RG Cable Guide, which emphasizes documenting the full RF chain rather than just the visible cable.

What recent Wi-Fi deployments are tightening the loss budget, and how should I respond?

Over the past few Wi-Fi generations, link budgets have not become more forgiving. They have become tighter. What used to work reliably at 2.4 GHz or early 5 GHz deployments now operates with far less margin, even when transmit power and antenna gain appear unchanged.

This shift has practical consequences for how wifi antenna cable runs are specified, routed, and documented.

Wi-Fi 6E and Wi-Fi 7: higher MCS, smaller margins

Wi-Fi 6E pushed unlicensed operation into the 6 GHz band, and Wi-Fi 7 raises the bar further with wider channels and higher-order modulation. These gains come at a cost: higher sensitivity to loss, reflection, and phase noise across the entire RF chain.

At these frequencies, small inefficiencies compound. A connector mismatch that was barely noticeable at 2.4 GHz can meaningfully reduce throughput at 6 GHz. Likewise, an extension cable that once felt “short enough” may now sit right on the edge of acceptable loss, especially when combined with adapters or feed-throughs.

The practical response is not to eliminate extension cables entirely, but to treat them as part of the RF budget rather than as neutral accessories. Length tiers should be chosen deliberately, and connector transitions should be minimized wherever possible.

FAQs

How can I confirm RP-SMA vs SMA on a router without opening the case?

Visual inspection is usually sufficient. Look at the external threads and then inspect the center conductor with a flashlight. The presence of a pin versus a socket determines SMA versus RP-SMA. No disassembly is required in most cases.

What length tiers are still safe at 6 GHz if I must route past a cabinet edge?

There is no universal limit, but in practice, keeping extensions at or below 0.5 m and minimizing adapters preserves margin in most indoor deployments. Beyond that, connector count becomes as important as length.

Is one male-to-female jumper better than two back-to-back adapters inside a chassis?

Almost always. A single jumper reduces interface count, lowers insertion loss, and removes a rigid mechanical joint that can loosen over time.

Can I use an RP-SMA antenna with an SMA jack and still meet EIRP limits?

Electrically, adapters change loss and can affect assumptions used in compliance calculations. Any cross-family pairing should be evaluated as part of the certified RF chain rather than treated as interchangeable.

What bend radius is acceptable for RG178 around standoffs or lid bosses?

A conservative guideline is a minimum bend radius of ten times the cable’s outer diameter. Tighter bends may work initially but tend to degrade reliability over time.

Which exact fields must appear on the PO so the order is not rejected by warehousing?

Connector family, center contact gender, end configuration, cable type, exact length, bulkhead or flange requirements, sealing accessories, and quantity should all be explicit. Ambiguity is the most common cause of order delays.

Closing perspective from real deployments

Most Wi-Fi systems that underperform in the field do not fail because of poor RF theory. They fail because small, late decisions quietly consume margin that the design never had to spare. A misidentified connector, an unnecessary adapter, or an extension cable added “just to make it fit” rarely looks dangerous in isolation.

At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, those details add up.

Treating the wifi antenna cable as part of the RF system rather than as a passive afterthought changes outcomes. Confirming SMA versus RP-SMA before ordering, choosing length tiers deliberately, minimizing transitions, and documenting intent clearly on the PO are not glamorous steps, but they are the ones that prevent rework and protect performance once the product leaves the bench.

If there is one consistent lesson from real deployments, it is this: the quiet parts of the RF chain deserve the same attention as the obvious ones.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.