RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Matching, and Ordering

Jan 3,2026

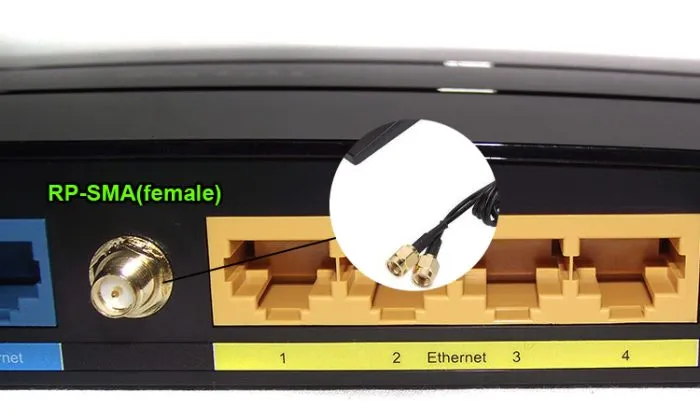

As the opening example of the article, this figure provides a concrete, real-world hardware scenario. It visually shows the source of the problem—this “ordinary-looking” connector on the device panel is the origin of many subsequent matching errors, thereby introducing the necessity for precise identification between RP-SMA and SMA.

How do I tell RP-SMA from SMA in 10 seconds?

Thread × pin/hole quick ID (device vs antenna)

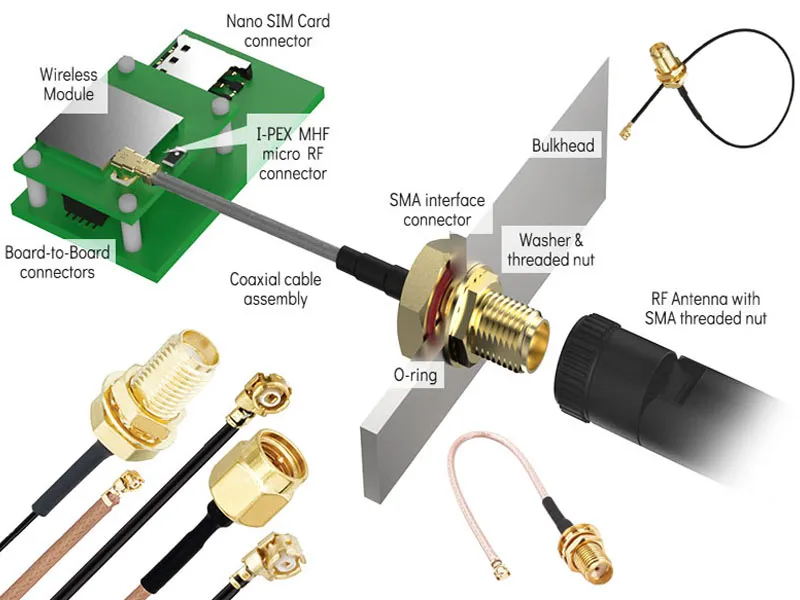

This figure is the core teaching tool for the “10-second identification method.” It visually summarizes the “thread × pin/hole” rule from the text, aiming to help readers move away from relying on the vague terms “male/female” and instead use objective physical features for unambiguous identification.

Ignore connector names entirely and look at only two physical features: whether the connector has external or internal threads, and whether the center contact is a pin or a hole. Those two observations uniquely identify the interface. An external thread with a center pin is SMA male. An external thread with a center hole is RP-SMA male. An internal thread with a center hole is SMA female. An internal thread with a center pin is RP-SMA female. This rule does not depend on vendor naming or market segment. It works because it is purely mechanical.

In practice, it helps to look at the center contact first. Many misidentifications happen because engineers instinctively check the threads, assume the rest, and move on. That shortcut is fast, but it fails often enough to cause real RF problems later.

Look-alike traps: mechanical fit does not mean RF compatibility

This figure establishes a correct example of “matching” by showing a standard, electrically compatible SMA male-female pair. Its primary function is to serve as a visual anchor: when readers understand how this pair perfectly mates via “external thread + center pin” and “internal thread + center hole,” they can more deeply comprehend why the “incorrect mixing” described later (e.g., screwing an SMA male into an RP-SMA female) prevents center contact connection, thereby interrupting the RF path. This figure concretizes the abstract concept of “compatibility.”

How do I match both ends once and avoid “fits but fails”?

Home router and access point default: RP-SMA-F device × RP-SMA-M antenna

This figure applies identification knowledge to practice, providing the “standard answer” for the first common application scenario (consumer market). It helps engineers build a correct mental model, reducing guesswork when faced with a vast array of router and AP products, while still reminding that final verification must be based on physical inspection.

Industrial and IoT default: SMA-F device × SMA-M antenna

SMA and RP-SMA connector mapping (threads, pin/hole, gender)

This figure is an extension and practical application of the information in Figure 2. It binds identification features to application scenarios, directly connecting theoretical knowledge to procurement and design decisions. This figure is intended to be printed or saved as a quick reference guide for final verification when ordering cables or antennas.

| Connector type | Threads | Center contact | Typical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMA male | External | Pin | Industrial antennas |

| SMA female | Internal | Hole | Industrial devices |

| RP-SMA male | External | Hole | Router antennas |

| RP-SMA female | Internal | Pin | Router and AP devices |

This table looks simple, but skipping it is one of the fastest ways to create ordering mistakes and returns. Many problems originate here, long before cable length or antenna gain is considered.

How long can I extend before 5 GHz or 6 GHz throughput drops?

When Wi-Fi antenna, SMA, or RP-SMA extension cables make sense

Field measurements show consistent patterns. Short extensions in the 0.1 m to 0.3 m range are usually safe, with loss present but rarely dominant. Around 0.5 m, throughput variability at 6 GHz becomes noticeable. Beyond 1 m, link margin should be recalculated rather than assumed. This behavior is not unique to one connector type. It applies equally to a wifi antenna extension cable, an sma extension cable, or an rp-sma extension cable. Frequency penalizes length regardless of naming.

Engineers who want a deeper background on how coaxial attenuation scales with frequency often start from general loss behavior before applying it to antenna extensions, as outlined in this RF cable overview: https://tejte.com/blog/rg-cable-guide/.

Connector and adapter penalties add up faster than expected

Extension Loss Quick Estimator

Why shorter almost always wins

Short extensions often solve mechanical problems cleanly—moving an antenna away from metal, clearing a lid, or reaching a better radiation spot. Those gains can outweigh the cable loss.

The problem starts when extensions are used as a convenience layer.

From field work and validation testing, typical patterns look like this for compact coax such as RG178:

- 0.1–0.3 m: usually invisible to throughput

- 0.5 m: margin starts to shrink

- 1 m or more: performance changes become measurable, especially uplink

This isn’t about one extra dB killing the link. It’s about erasing the safety margin that kept the system stable under temperature, orientation, and traffic load.

Why adapters often hurt more than length

Located in the section discussing extension cable length, this figure uses a simple visual comparison to reinforce the recommendations in the text. It goes beyond specific numerical calculations to convey a design philosophy: in the RF domain, a simple and direct path is often the most robust choice for performance.

Do I actually need a panel feed-through, and how do I size an SMA bulkhead?

Panel thickness is not the real number you are sizing for

Many engineers start by measuring the panel thickness and selecting a bulkhead with “a bit more thread.” That approach works sometimes, but it fails often enough to be a pattern. The connector does not clamp against the panel alone. It clamps against a stack.

That stack typically includes the panel, a flat washer, an O-ring or gasket, sometimes a sealing cap, and finally the nut itself. If even one of those elements is ignored, the connector may feel tight while still lacking real mechanical preload.

In practice, what matters is thread engagement after compression. If the nut only catches one or two threads once everything is stacked, vibration will eventually loosen it. A safer target is roughly two and a half to three full threads engaged under final torque. Less than that is asking for trouble. More than that is usually fine, but it may create clearance issues inside the enclosure.

Sealing failures are usually compression failures

When water ingress shows up in the field, the connector often gets blamed. In many cases, the connector is fine. The sealing geometry is not.

O-rings seal by compression, not by contact. If the bulkhead is too short, the O-ring barely compresses. If it is too long, the O-ring is crushed beyond its working range. Both conditions reduce long-term reliability, especially when temperature cycles are involved. What feels acceptable during assembly can look very different after a few hundred thermal cycles outdoors.

Single-nut bulkhead or flange mount: this is not just convenience

This is a detailed exploded assembly diagram illustrating how to safely and shieldedly route signals from an internal wireless module (e.g., M.2 card) to an external antenna via an SMA bulkhead connector. It clearly labels each component and their assembly sequence from the micro RF connector to the external SMA interface.

Single-nut bulkheads are popular because they are fast. One hole, one nut, done. For indoor equipment that never moves, that is often enough. Problems start when the same hardware is used in mobile or outdoor environments.

Flange-mounted connectors spread mechanical load across multiple fasteners. That extra work pays off when vibration, torque, or cable weight are present. In vehicle-mounted systems or exposed enclosures, a flange mount is often the difference between a connector that stays put and one that slowly rotates over time.

Inside the chassis: antenna cable or male-to-female jumper?

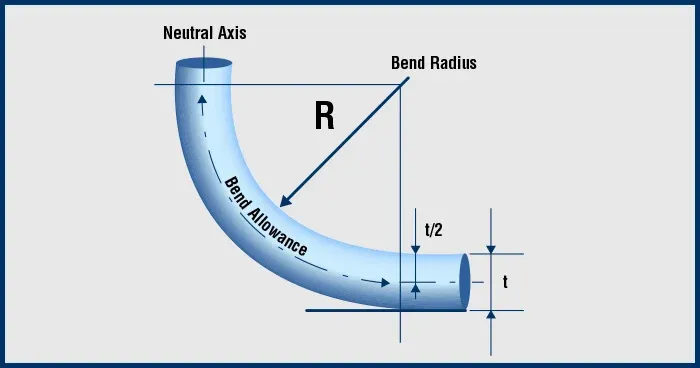

Bend radius causes more issues than length

Inside an enclosure, the problem is rarely electrical length. It is geometry. Tight bends introduce impedance changes that do not always show up on a bench test. They do show up after repeated vibration or thermal cycling.

A conservative rule that works across common coax types is a minimum bend radius of about ten times the cable’s outer diameter. Smaller bends may work initially, but they reduce margin. Over time, they also stress the shield and dielectric in ways that are hard to diagnose later.

Strain relief is not optional

A cable that floats freely between two connectors will move. That movement transfers directly to the connector interface. Eventually, contact quality suffers. This is not theory; it shows up in returned hardware.

A simple tie-down or adhesive mount near the connector dramatically improves long-term stability. It is a small detail, but it matters more than shaving a few millimeters of cable length.

One jumper is almost always better than two adapters

Electrically, an SMA antenna cable and an SMA male-to-female jumper behave the same if the construction is identical. The difference is practical. Using a single jumper with the correct ends avoids extra interfaces. Every adapter adds loss, reflection, and a mechanical joint that can loosen.

In tight enclosures, adapter chains are a common cause of intermittent issues. They are easy to assemble and hard to debug later.

Clearance to metal is about consistency, not fear

This figure provides theoretical support for cable bend limitations, going beyond simple empirical advice. It shows the relationship between the neutral axis, material tension, and compression during bending, helping readers understand why violating this rule leads to irreversible gradual performance degradation, thereby fostering respect during routing.

Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack, and what am I giving up?

The loss is not just insertion loss

Each adapter introduces a small amount of insertion loss. More importantly, it adds another discontinuity. On paper, that may look negligible. In a real system operating near its margin, it is not.

At 6 GHz, those small penalties accumulate quickly. What worked at 2.4 GHz without issue can become unstable simply because the system no longer has room for extra interfaces.

Compliance questions do not disappear

The usual order of preference

This figure crystallizes the engineering wisdom of the entire article. Facing the practical problem of “what to do when a mismatch already exists,” it provides a proven, hierarchical action guide. It visually communicates the core principle that “adapters are a last resort,” helping teams make decisions beneficial for long-term reliability even under project pressure.

Turning identification into ordering discipline

Why these details matter more now than before

As systems move deeper into the 6 GHz band, tolerance shrinks. Loss that used to be invisible becomes measurable. Reflection that once affected edge cases becomes performance-limiting. In that environment, RP-SMA vs SMA is no longer a clerical detail. It is part of system design.

The projects that hold up over time tend to share the same traits. They identify connectors visually, keep extension lengths conservative, and treat mechanical decisions with the same seriousness as electrical ones.

Should I adapt, replace, or redesign when RP-SMA and SMA do not match?

By the time a mismatch is discovered, the project is usually already moving. Hardware is built. Enclosures are drilled. Schedules are tight. That is why adapters get used so often. They feel like the smallest possible change.

They are rarely the best one.

Adapters solve geometry, not system margin

An adapter only addresses one problem: mechanical incompatibility. It does nothing to improve signal integrity. In fact, it always makes the RF chain slightly worse. Sometimes that penalty is small enough to ignore. Sometimes it is not.

At lower frequencies, the system often absorbs the loss. At higher frequencies, especially in the 6 GHz band, the margin is thinner. An extra interface that seemed harmless during early testing can become the limiting factor once temperature, aging, and production variation enter the picture.

This is why teams that work with high-volume or high-frequency designs tend to be conservative about adapters. They are used when unavoidable, not as a standard fix.

Replacement is usually cheaper than it feels

Replacing an antenna or cable with the correct native connector often looks expensive at first glance. In practice, it is frequently cheaper than the downstream cost of debugging intermittent issues, handling returns, or explaining performance variation to customers.

There is also a psychological factor. Once an adapter is added, it becomes invisible. Future engineers assume it belongs there. Over time, small inefficiencies stack up. Removing the mismatch at the source prevents that accumulation.

Redesign is not always dramatic

Redesign does not necessarily mean changing the RF architecture. In many cases, it means moving a connector, shortening a run, or selecting a different bulkhead length. Small mechanical adjustments early in a revision cycle often eliminate the need for adapters entirely.

Teams that plan for connector orientation and cable routing at the enclosure stage tend to avoid these problems later. Teams that treat connectors as interchangeable parts tend to revisit them repeatedly.

What belongs on a purchase order so returns do not happen?

The fields that actually matter

At minimum, the following should be fixed and explicit before ordering:

- Device-side connector type, including pin or hole

- Antenna-side connector type

- Required gender at each end of the cable

- Target length range, not just a nominal value

- Environmental expectations (indoor, semi-outdoor, outdoor)

- Quantity and revision consistency

Leaving any of these open invites assumptions. Assumptions vary between suppliers, assemblers, and even different people on the same team.

Why length ranges are better than single numbers

Specifying a single length looks precise, but it often creates problems. Assemblies vary. Routing changes slightly. A cable that fits tightly in one unit may be stressed in another. Giving a small acceptable range allows for practical routing while keeping RF impact predictable.

Teams that specify only exact lengths tend to revise those numbers later. Teams that specify ranges tend not to.

Turning identification into a repeatable decision

Once the device port is identified visually and the antenna interface is confirmed, the rest of the decision tree becomes mechanical. End types, length class, bulkhead or direct mount, sealing or no sealing. When that logic is written down once, it can be reused across projects and suppliers.

This is where many experienced teams see the biggest reduction in returns. Not from better RF design, but from better ordering discipline.

Why Wi-Fi 7 and 6 GHz change how strict we need to be

Earlier generations of Wi-Fi were forgiving. Loss budgets were generous. Reflections mattered, but not immediately. That environment allowed many borderline decisions to pass unnoticed.

The move into the 6 GHz band changes that dynamic.

Small penalties stop being invisible

Insertion loss that once disappeared into noise now shows up as throughput variation. Reflection that once affected only edge cases now impacts stability. Connector quality, interface count, and cable routing all matter more than they did before.

This does not mean designs must become exotic. It means tolerances are tighter. Details that were once optional are now part of the performance envelope.

RP-SMA vs SMA becomes a system choice, not a label

At this point, choosing between RP-SMA and SMA is no longer just about compatibility with existing antennas. It affects how many interfaces exist in the chain, how easily the system can be extended, and how predictable performance will be over time.

Systems that choose a connector strategy early and stay consistent tend to age well. Systems that mix conventions tend to accumulate adapters, exceptions, and undocumented decisions.

What experienced teams do differently

Across different industries and applications, a few patterns repeat:

They identify connectors visually rather than trusting labels.

They keep extension lengths conservative, especially above 5 GHz.

They avoid adapter chains unless there is no alternative.

They treat mechanical mounting with the same seriousness as electrical design.

They write ordering requirements as constraints, not suggestions.

None of these practices are complicated. They are simply consistent.

Closing perspective

RP-SMA vs SMA is not difficult to understand. What makes it challenging is how easy it is to dismiss. The connectors are small. The differences are subtle. The consequences are delayed.

Projects that perform well over time usually do not rely on clever RF tricks. They rely on disciplined decisions made early and documented clearly. Connector choice is one of those decisions. Once it is made correctly, it tends to disappear from the problem list entirely.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.