SMA Extension Cable Length Loss & Bulkhead Guide

Jan 2,2025

As the opening figure of the article, it aims to establish the core understanding: an SMA extension cable is not a harmless “add-on.” Through visual metaphor, it links concepts like “added late,” “inexpensive” with the hidden risk of “eroding system margin at high frequencies,” guiding readers to pay attention to subsequent identification, matching, and length planning.

An SMA extension cable rarely gets much attention during early design. It’s passive. It’s inexpensive. And it’s often added late—after the enclosure, the antenna, and even the compliance plan are already “locked.”

In real Wi-Fi and IoT systems, that short coax run often decides whether a link feels solid or fragile.

At 2.4 GHz, small mistakes hide easily. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, they don’t. A mismatched connector, an unnecessary adapter, or an extra half-meter of cable can quietly erase link margin, push MCS rates down, or make throughput unpredictable under load.

This guide focuses on what actually breaks projects in the field: fast connector identification, correct end-to-end matching of an sma extension cable, and realistic expectations for extension length before losses become noticeable.

If you want the broader context on coax attenuation and cable families, it helps to keep the big picture in mind—see the RG loss overview in the RG Cable Guide and come back here for the hands-on decisions.

How do I tell SMA from RP-SMA in 10 seconds?

Most extension mistakes start with a wrong assumption at the port. SMA and RP-SMA look nearly identical, and that similarity is exactly why they cause trouble.

You don’t need a datasheet. You don’t need to open the enclosure. You just need to check two physical cues—in the right order.

Thread × pin/hole quick ID (device vs antenna)

Start with the device port, not the cable.

- Look at the thread location

- External thread → male-style body

- Internal thread → female-style body

- Check the center contact

- Visible pin → “pin”

- No pin → “socket / hole”

Combine the two observations:

- External thread + pin → SMA male

- External thread + hole → RP-SMA male

- Internal thread + hole → SMA female

- Internal thread + pin → RP-SMA female

That’s the entire identification logic. Everything else—labels, product listings, even some drawings—can mislead you.

Field note:

Many Wi-Fi routers use RP-SMA female ports. Many industrial radios use SMA female ports. Assuming one or the other without checking is how returns start.

RP-SMA vs SMA look-alike trap and mismatch risks

The most common failure mode isn’t “won’t screw on.” It’s “screws on fine, performs poorly.”

Typical traps include:

- An SMA male antenna forced onto an RP-SMA female router port via an adapter

- Mixing an RP-SMA extension cable into an otherwise SMA chain

- Using adapters as a quick gender fix instead of correcting the cable spec

Mechanically compatible does not mean electrically optimal. Each mismatch adds loss and reflection—effects that become obvious at higher bands.

For a deeper comparison focused on avoiding returns, the practical checks in RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Match & Ordering Guide are worth reviewing alongside this section.

How do I match both ends of an SMA extension cable without mistakes?

Typical chain: device → extension → antenna

This figure is located in the chapter discussing how to correctly match both ends of a cable. It concretizes the abstract “matching logic” through a specific hardware application scenario (possibly involving GPS, SDR). The note in the figure, “Please Note: this is SMA Connector, not RPSMA Connector,” strongly echoes the importance of the “10-second identification method” mentioned earlier and emphasizes the necessity of confirming the connector standard starting from the device port.

A common, low-risk chain looks like this:

Device SMA-Female

Extension cable SMA-Male to SMA-Female

Antenna SMA-Male

This layout works because:

- The standard stays SMA end-to-end

- Gender transitions are intentional, not patched

- No adapters are required

If any element in the chain is RP-SMA, the entire logic must flip. Mixing standards mid-chain is where confusion—and loss—creeps in.

Electrical, not just mechanical: impedance and reflection

Every connector interface introduces:

- A small impedance discontinuity

- A bit of return loss

- Some insertion loss

Individually, these seem minor. Together, they stack.

At 2.4 GHz, the penalty might be invisible.

At 5 GHz or 6 GHz, it often shows up as:

- Reduced high-order MCS stability

- Asymmetric uplink vs downlink performance

- Lower margin under temperature or load changes

That’s why “it threads smoothly” is never a sufficient acceptance test for an sma extension cable. Electrical continuity matters just as much as mechanical fit.

How long can I extend before 5/6 GHz range drops?

This is where expectations and physics collide. There is no universal safe length—only trade-offs.

At higher frequencies, attenuation rises quickly, and connector losses matter more than most people expect.

When a Wi-Fi antenna extension cable makes sense

As a practical rule of thumb for compact coax (for example, RG178-class cables):

- 0.1–0.3 m: usually safe, even at 6 GHz

- 0.5 m: noticeable margin loss in many systems

- 1 m or more: requires deliberate link budgeting

If you’re extending primarily to fix enclosure layout or antenna placement, shorter is almost always better than thicker.

Connector and adapter penalties—keep the chain short

In field measurements and production testing, engineers often use a conservative estimate:

- ~0.2 dB per connector interface

- ~0.2–0.3 dB per simple adapter

This doesn’t replace lab characterization, but it’s accurate enough to guide decisions early—before hardware is committed.

If you find yourself adding adapters just to “make it work,” that’s usually the signal to re-spec the cable instead.

How long can I extend before 5 / 6 GHz range actually drops?

Extension Loss Estimator

This is usually the moment where someone asks for a clean number.

“Can I run one meter?”

“Is half a meter safe at 6 GHz?”

In practice, there isn’t a single cutoff. Loss builds gradually, then suddenly starts to matter. What decides where that tipping point lands is a mix of frequency, cable loss per meter, and how many interfaces you’ve stacked into the chain.

At 2.4 GHz, you can get away with things.

At 5 GHz and especially 6 GHz, you rarely can.

When a Wi-Fi antenna extension cable stops being “cheap”

Short extensions often solve mechanical problems cleanly—moving an antenna away from metal, clearing a lid, or reaching a better radiation spot. Those gains can outweigh the cable loss.

The problem starts when extensions are used as a convenience layer.

From field work and validation testing, typical patterns look like this for compact coax such as RG178:

- 0.1–0.3 m: usually invisible to throughput

- 0.5 m: margin starts to shrink

- 1 m or more: performance changes become measurable, especially uplink

This isn’t about one extra dB killing the link. It’s about erasing the safety margin that kept the system stable under temperature, orientation, and traffic load.

Why adapters often hurt more than length

Engineers often underestimate connectors because each one “only costs a little.” The problem is accumulation.

Each interface adds:

- mismatch

- reflection

- variability between units

Two adapters plus an extension can easily cost more than doubling the cable length. That’s why fixing the chain layout usually works better than upgrading to a slightly lower-loss cable.

Extension Loss Quick Estimator

Inputs

- Frequency: 2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz

- Cable: e.g., RG178

- Length (L): meters

- Connector count (n)

- Adapter present: Yes / No

Engineering estimate

Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

The 0.2 dB per connector figure is a conservative planning value, not a lab spec. It’s meant to catch bad decisions early.

Outputs

- Estimated total loss

- Suggested length tier: 0.1 / 0.3 / 0.5 / 1 / 2 m

- Recommendation:

- shorten

- change cable type

- remove adapters

Use this before hardware is frozen. It saves time later.

Do I need a panel feed-through, and how long should the SMA bulkhead thread be?

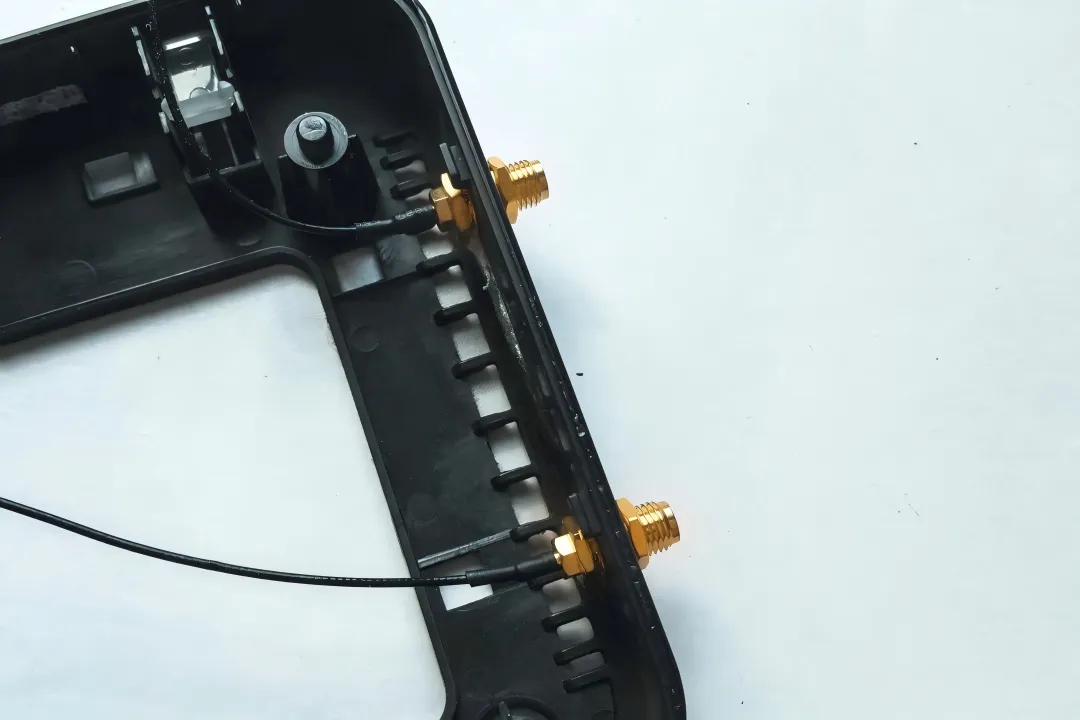

This figure is the visual core of the section “how long should the SMA bulkhead thread be?”. It associates the “stack height” concept described in the text (panel, washer, gasket, nut) with a specific connector object, helping engineers understand why selection cannot be based on panel thickness alone and how neglecting mechanical details can lead to long-term reliability issues (e.g., loosening, seal failure).

An SMA bulkhead looks simple on a drawing. In reality, most problems show up months later—after vibration, handling, or temperature cycling.

The usual failure isn’t electrical. It’s mechanical.

Stack height beats nominal thread length

Designers often size bulkheads using only panel thickness. That’s almost never enough.

A real installation includes:

- panel material

- one or more washers

- gasket or O-ring (compressed, not free height)

- nut engagement

- some tolerance for assembly

Miss one of these and the connector may feel solid today but loosen over time.

If you’re evaluating drilling and sealing trade-offs in parallel, the practical guidance in SMA Bulkhead Panel Drilling & IP67 Sealing in Practice fits naturally with this sizing step.

Bulkhead Thread Length Calculator

Inputs

- t_panel: panel thickness (mm)

- t_washer: washers combined (mm)

- t_gasket: compressed gasket height (mm)

- h_nut: effective nut engagement (mm)

- a_allow: assembly allowance (0.5–1 mm)

Calculation

L_required = t_panel + t_washer + t_gasket + h_nut + a_allow

Outputs

- Recommended thread length

- Whether a long-thread bulkhead is needed

- Whether a 2-hole or 4-hole flange would be safer mechanically

In vibration-prone enclosures, extra engagement usually pays for itself.

Inside the enclosure: SMA antenna cable or male-to-female jumper?

This figure shifts the discussion focus from external extension cables and bulkhead connectors to the inside of the device. It visualizes the rule of thumb “bend radius ≥ 10x outer diameter” and good practices like strain relief through simple bundling. The figure emphasizes the importance of mechanical reliability in internal routing for long-term RF performance stability, pointing out that many field performance drifts that are hard to debug stem from such overlooked mechanical stresses.

Bend radius and strain relief still matter

A simple rule holds across small-diameter coax:

Minimum bend radius ≥ 10× outer diameter

Violating this doesn’t cause instant failure. Instead, performance drifts slowly—exactly the kind of issue that’s hardest to debug in the field.

Support the cable. Don’t clamp it flat. Avoid sharp edges.

EMI and proximity to metal

Inside metal housings:

- keep coax away from sharp edges

- avoid long parallel runs with noisy digital traces

- route RF early, not as an afterthought

These habits often buy more stability than changing cable type.

Can I adapt an RP-SMA antenna to an SMA jack—and get away with it?

Compatibility isn’t the same as performance

Adapters add loss and variation. In certified products, they also complicate EIRP consistency. What passed in the lab may not match production units.

That’s why many teams treat adapters as lab tools, not shipping solutions.

Better options, in order

- Match connector types directly

- Shorten the RF path

- Reduce interface count

- Use adapters only when unavoidable

This approach avoids surprises late in validation.

What must I confirm before ordering to avoid returns?

SMA Extension Cable Ordering Checklist

Most returns don’t happen because a supplier shipped the wrong item.

They happen because the order itself was ambiguous.

An sma extension cable looks simple on a quote, but small omissions—connector type, gender, or bulkhead details—are enough to make a cable unusable once it arrives on the bench.

The safest approach is to order extensions the same way you would order an RF module: explicitly, even if it feels redundant.

Why “SMA extension cable” is not a complete description

From a purchasing standpoint, the phrase hides several decisions:

- SMA or RP-SMA

- Pin or socket at each end

- Straight cable or panel feed-through

- Bare connector or waterproof-cap version

- Mechanical constraints from the enclosure

If any one of these is assumed instead of specified, you’re relying on luck.

That’s also why mixing email notes, screenshots, and verbal confirmations tends to fail. Clear text beats pictures every time.

SMA Extension Cable Ordering Checklist (Tick-Off)

Core RF parameters

- Connector standard: SMA / RP-SMA

- Center contact: pin / hole

- Ends: M–F / M–M / F–F

- Cable type: e.g., RG178

- Length: 0.1–2 m

Mechanical / installation

- Bulkhead or flange: Yes / No

- Thread length requirement (if bulkhead)

- Panel thickness and hole size

- Waterproof cap: Yes / No

Commercial

- Quantity

- Target application (router, gateway, test fixture, enclosure pass-through)

Ticking every line may feel slow. It is still faster than reworking a build after cables arrive.

Copy-ready PO note

SMA extension cable, SMA-M to SMA-F, RG178, length 0.3 m.

No adapters.

For direct connection between SMA-F device port and SMA-M antenna.

No RP-SMA.

Not for bulkhead mounting.

Short, explicit notes like this remove interpretation entirely.

If your order includes a panel feed-through, reference your calculated thread length from the bulkhead sizing step in Part 2. That one line prevents most mechanical mismatches.

How this fits into a larger RF decision flow

Extension cables don’t exist in isolation. They sit between cable loss, antenna behavior, and enclosure constraints.

If you find yourself pushing extension length beyond what the loss estimator suggests, it’s often a sign to revisit upstream decisions—antenna placement, enclosure geometry, or even cable family choice. Looking back at system-level attenuation trends in the RG Cable Guide can help put those trade-offs in context.

Likewise, if repeated orders fail due to connector confusion, the identification logic summarized earlier pairs well with the deeper compatibility checks in RP-SMA vs SMA: Fast ID, Match & Ordering Guide.

These links aren’t prerequisites. They’re escape hatches when a local fix starts turning into a system problem.

Final engineering takeaway

An SMA extension cable isn’t dangerous because it’s lossy.

It’s dangerous because it looks harmless.

At higher bands, small losses matter. Small mismatches accumulate. Mechanical shortcuts turn into RF variability months later.

If you:

- identify the port correctly,

- match the chain intentionally,

- budget loss conservatively, and

- order with zero ambiguity,

extension cables stay what they should be—quiet, predictable, and invisible to system performance.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.