RP-SMA Connector: Router ID, Matching & Extension Guide

Dec 30,2025

Located in the article’s introduction, this figure establishes the core awareness: problems around the RP-SMA connector often stem from subtle, unnoticed assumptions rather than obvious design errors, and their impact is cumulative.

Wireless systems rarely fail because someone misunderstood RF theory. Much more often, they fail because a small assumption slipped through late in the build. A connector that looked right. A cable that threaded on smoothly. An extension added after the enclosure layout changed.

Problems around the rp-sma connector live in that gray zone. Nothing looks broken. Everything screws together. Yet range feels inconsistent, higher data rates drop first, and 5 GHz or 6 GHz links behave as if the margin quietly vanished. The issue is rarely dramatic—it’s cumulative.

This article focuses on what actually happens in real hardware. Not idealized diagrams, not catalog shorthand, but the identification habits, matching logic, and extension decisions engineers rely on when they want a system to behave the way the link budget says it should. If you’ve ever thought, “It fits—so why does it perform worse?”, this guide was written for you.

Is my router/AP jack RP-SMA or SMA—how do I tell fast?

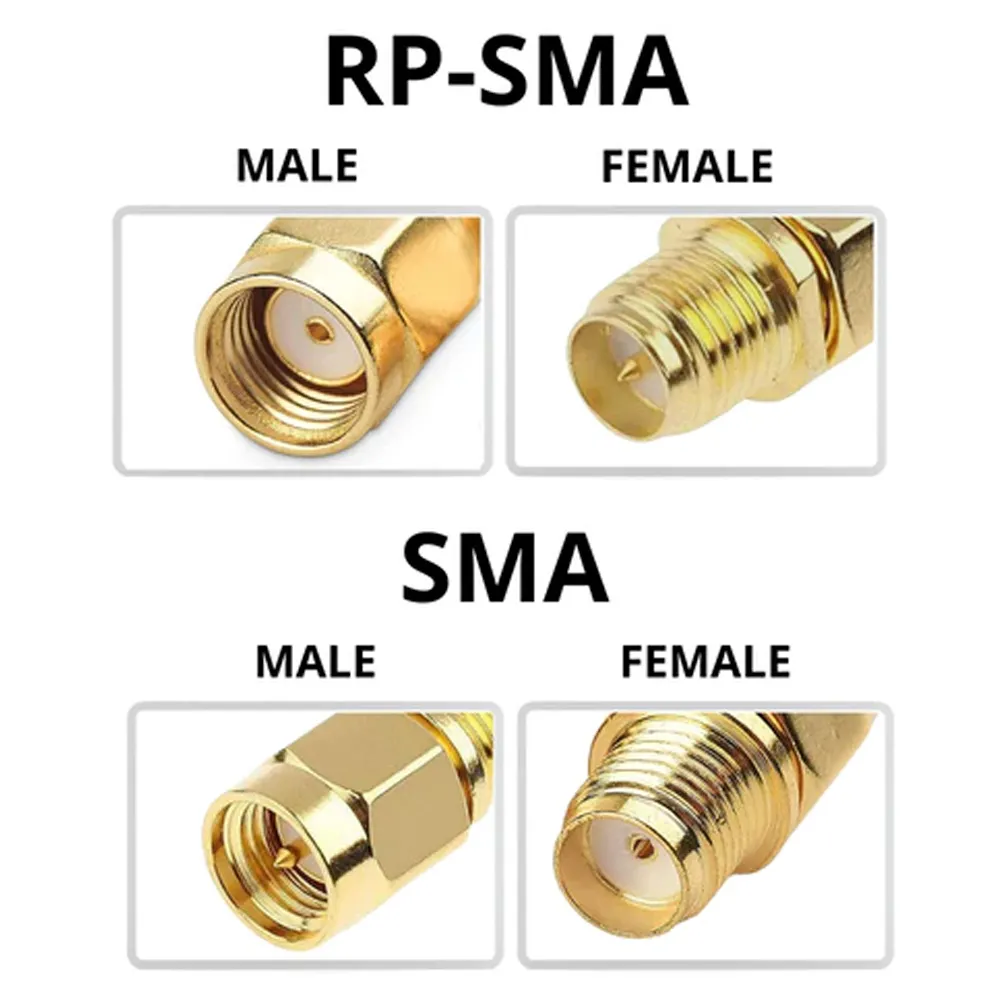

This figure serves as the starting point for the connector identification discussion, visually presenting the different physical forms that the term “SMA” may encompass, setting the stage for the subsequent detailed “10-second identification method.”

Most connector mistakes start with labels. “SMA” appears everywhere—product listings, bags, invoices—yet that word alone hides the one detail that matters most electrically. Fortunately, you don’t need calipers, part numbers, or teardown photos to identify a router or access-point port.

You only need to look at two physical features, and it takes about ten seconds.

10-second thread × pin/hole quick ID

Figure plays a key role as a “pitfall avoidance guide.” It juxtaposes two connector variants that look similar but have opposite polarities and are incompatible, emphasizing the necessity of careful identification in specific scenarios like Wi-Fi equipment and antenna testing. This figure is the first line of defense against low-level but costly mistakes.

Forget the words “male” and “female” for a moment and look directly at the connector.

First, identify where the threads are:

- Threads on the outside of the connector body

- Threads inside the connector

Second, check the center contact:

- A visible pin

- Or a hole (no pin)

Those two observations place the connector into one of four unambiguous categories:

| Thread location | Connector type | Center contact |

|---|---|---|

| External | RP-SMA female | Hole (no pin) |

| External | SMA male | Pin |

| Internal | RP-SMA male | Pin |

| Internal | SMA female | Hole |

In day-to-day work, this visual check is faster—and more reliable—than any datasheet description. It also explains why so many assemblies “almost” work.

In practice, most consumer Wi-Fi routers and access points expose an RP-SMA female jack: external threads with no center pin. Once that image is fixed in your mind, many ordering mistakes stop happening.

Common habits on routers/APs and IoT gateways

This figure provides a broader context of RF connectors, implying that the reverse polarity concept is not limited to SMA. It supports the subsequent discussion about different device types (consumer vs. industrial) conventionally using different connectors.

Without listing brands, industry patterns repeat.

Consumer routers and office access points nearly always use RP-SMA female ports on the enclosure. Industrial IoT gateways, especially those built into metal housings, more often use standard SMA female ports instead. Internal radio modules rarely expose SMA at all, relying on micro connectors that require pigtails.

Knowing these habits gives you a built-in sanity check. If a listing claims universal compatibility but contradicts what you see on the device, trust the hardware. Engineers who want a broader context on how coax loss accumulates across different cable families often review the overall behavior outlined in the RG Cable Guide before locking down connector and extension decisions.

How do I match an rp-sma connector to antennas and extensions without mistakes?

Male/Female mapping and typical pairs

This figure visualizes the principle of “conservative matching,” showing the standard path from an RP-SMA female device port to an RP-SMA male antenna (or via a male-to-female extension), emphasizing that back-to-back adapters should be avoided.

The most common—and electrically clean—pairing looks like this:

- Device port: RP-SMA female (external thread, no pin)

- Antenna: RP-SMA male (internal thread, center pin)

When an extension is required, the same logic applies:

- Extension cable: RP-SMA male-to-female

The male end mates to the device; the female end accepts the antenna.

This approach avoids stacking adapters and keeps the RF path predictable. If a proposed setup requires two adapters back-to-back just to make the genders line up, that’s usually a warning sign rather than a solution.

RP-SMA vs SMA: differences and the “fits but not compatible” trap

This figure highlights the core of the risk of mixing RP-SMA and SMA—mechanical compatibility masks electrical incompatibility. It explains why many systems “almost” work but perform unreliably.

This is where even experienced installers get caught—often once, sometimes twice.

An SMA male will physically screw onto an RP-SMA female. The threads are identical. Engagement feels solid. Nothing during assembly signals a problem. Electrically, however, the center contacts are wrong for each other.

Sometimes the pin barely touches. Sometimes it doesn’t touch at all. Sometimes it works on the bench and fails later after vibration or temperature cycling. The failure mode is subtle: higher VSWR, reduced margin at higher frequencies, and links that feel unstable under load.

A deeper explanation of why this mismatch causes so many returns is covered in the RP-SMA vs SMA identification guide, but the practical takeaway is simple: if the center-pin logic doesn’t match, assume RF performance will suffer—even if the connector threads mate perfectly.

How long can I extend before 5/6 GHz range drops?

This figure reiterates the correct pairing logic in its simplest form, serving as a baseline reference before discussing derived issues such as extension cables and adapters.

When Wi-Fi antenna extensions actually make sense

Connector and adapter penalties in real systems

Extension Loss Estimator

Inputs

Frequency (2.4 / 5 / 6 GHz), cable type (RG178 default), length L (m), number of connectors n, adapter present (Y/N)

Estimator

Loss (dB) ≈ α(Frequency, Cable) × L + 0.2 × n

Typical real-world α for RG178

2.4 GHz ≈ 1.0 dB/m

5 GHz ≈ 1.9 dB/m

6 GHz ≈ 2.2 dB/m

Output

Estimated total loss, suggested length tier (0.1 / 0.3 / 0.5 / 1 / 2 m), and guidance on whether shortening the run or switching to a lower-loss cable is advisable.

A practical takeaway many teams learn the hard way: at 6 GHz, moving from 0.3 m to 0.5 m often costs more margin than expected—before connectors are even counted.

Do I need a panel feed-through—how do I size an SMA bulkhead?

This figure concretizes the abstract concept of a “bulkhead connector,” helping readers understand the subsequent discussion on mechanical installation details such as “stack height,” washers, and gaskets.

Panel feed-throughs solve real problems. They make antennas serviceable, reduce strain on internal radios, and clean up enclosure layouts. They also introduce mechanical variables that are easy to underestimate until vibration, sealing, or torque becomes an issue.

The electrical side of an sma bulkhead is usually straightforward. The mechanical side is where most mistakes hide.

Stack height: panel + washer + gasket + cap

Bulkhead sizing fails when people measure only the panel thickness. In practice, the connector must pass through a stack, not a single sheet.

A realistic stack often includes:

- Panel thickness (aluminum, steel, or plastic)

- Flat washer or star washer

- O-ring or gasket (for sealing)

- Optional weather cap or sealing nut

Add those together, then select a bulkhead with enough thread length to leave one to two full threads visible after tightening. Less than that and the nut bottoms out before achieving proper compression. More than that is usually fine, but may interfere with internal clearances.

A common field mistake is choosing the shortest possible bulkhead “because it fits.” It may assemble cleanly on the bench, then loosen after a few thermal cycles or vibration exposure. Engineers who deal with outdoor or vehicle-mounted systems often prefer a small margin rather than a perfect flush.

For a deeper walk-through on drilling, sealing, and thread engagement in real enclosures, the practical notes in SMA Bulkhead Panel Drilling & IP67 Sealing in Practice expand on these mechanical trade-offs without turning them into theory.

2-/4-hole flange vs single-nut locking

Bulkheads fall into two mechanical families:

Single-nut bulkhead

- Fast to install

- Minimal panel footprint

- Adequate for indoor or low-vibration environments

2- or 4-hole flange mount

- Better resistance to rotation

- More consistent gasket compression

- Preferred for outdoor, mobile, or industrial cabinets

If you’ve ever seen an antenna slowly rotate itself loose over months, you already understand why flanges exist. They don’t change RF performance. They change how long the system stays aligned with your original assumptions.

What should I use inside the chassis: sma antenna cable or a male-to-female jumper?

This figure supports the argument that “using a male-to-female jumper inside the chassis is better than a rigid direct connection,” demonstrating good routing practices through examples, including service loops and avoiding sharp bends.

Bend radius, strain relief, and routing discipline

A simple rule survives most audits:

Minimum bend radius ≥ 10× cable outer diameter

For thin coax like RG178, this is easy to meet. Problems arise near hinged lids, tight corners, or sharp stamped metal edges. Coax that is forced into a tight bend doesn’t usually fail immediately. It degrades slowly, often showing up first as intermittent performance at higher frequencies.

Strain relief is equally important. Even light vibration benefits from it. Simple methods work:

- Tie-downs near bulkheads

- Adhesive mounts with cable clips

- Gentle service loops rather than taut runs

These aren’t aesthetic choices. They directly affect long-term impedance stability.

EMI, grounding, and metal spacing

Coax routing inside a chassis should avoid:

- High-speed digital edges

- Switching inductors from DC/DC converters

- Sharp grounded metal edges that can pinch the dielectric

Keep some spacing where possible. Where not, route deliberately and secure the cable so it doesn’t migrate over time. Engineers who underestimate this often end up chasing “mystery noise” that only appears after the enclosure is closed.

Can I adapt an rp-sma antenna to an SMA jack—what’s the real cost?

This figure embodies the solution of an “adapter,” but also serves as a warning: while it solves mechanical mismatch, it introduces new electrical and reliability problems, especially at high frequencies.

Physical compatibility vs RF performance vs compliance

From a mechanical standpoint, adapters solve the problem instantly. From an RF standpoint, they add:

- Extra insertion loss

- Additional reflection points

- More uncertainty in the RF chain

At lower frequencies, this may be tolerable. At 5 GHz and 6 GHz, the margin shrinks quickly. In regulated products, this can also complicate EIRP calculations. Conducted power may stay the same, yet radiated performance shifts just enough to matter.

This distinction—between what works physically and what behaves well electrically—is the root of many late-stage surprises.

“Works, but not recommended” alternatives

Before committing to adapters, consider alternatives that often cost less in the long run:

- Use an antenna with the native connector that matches the device

- Replace two adapters with a single custom jumper

- Shorten the RF chain instead of extending it

Teams that build multiple SKUs often standardize connector logic early to avoid adapter creep later. It’s not glamorous, but it saves time.

How do extension choices interact with compliance and margin?

This question usually appears late, often after the hardware is “done.” That timing makes it dangerous.

Every connector, adapter, and centimeter of coax shifts the balance between conducted power, antenna efficiency, and radiated output. Individually, these shifts are small. Together, they define whether the product passes with margin—or scrapes through.

When engineers evaluate extension length using the loss estimator from the previous section, the goal isn’t precision to the tenth of a dB. The goal is awareness. If the math shows the margin shrinking, it’s usually cheaper to shorten the run or upgrade the cable than to debug compliance failures later.

For a broader perspective on how connector choices affect ordering accuracy and returns, many teams cross-check their assumptions against the workflow outlined in RP-SMA Connector Identification & Selection: How to Avoid Mismatch and Returns as a final sanity check.

Port ID & Ordering Decision Tree

Inputs

- Device port: SMA or RP-SMA, pin or hole

- Antenna port

- Panel feed-through required: Yes / No

- Length: 0.1–2 m

- Waterproofing needed: Yes / No

- Quantity

Logic → Output

- Recommended connector genders

- Extension type (M–F or M–M)

- Bulkhead required or not

- Suggested length tier

This logic doesn’t eliminate judgment. It eliminates assumptions.

Copy-ready PO note

“RP-SMA male to RP-SMA female extension, RG178, 0.3 m, no bulkhead, indoor enclosure.”

That single sentence answers most supplier clarification emails before they’re written.

Why experienced teams standardize connector logic early

After a few product cycles, many teams converge on a simple rule: decide connector logic once, then defend it. Every deviation adds adapters, documentation, and risk. Standardization doesn’t mean inflexibility. It means knowing exactly when you’re making an exception—and why.

This mindset is especially valuable as frequencies climb. What felt forgiving at 2.4 GHz becomes less tolerant at 6 GHz. Small decisions stop being small.

What belongs on my PO so I avoid returns?

By the time a return happens, the mistake has already been paid for—often twice. Shipping, rework, emails, and lost schedule time usually trace back to one missing detail in the purchase order.

With rp-sma connector assemblies, ambiguity is the enemy. The parts themselves are rarely wrong. The assumptions around them are.

Port Identification & Ordering Decision Tree

This decision tree doesn’t replace engineering judgment. It removes guesswork.

Inputs

- Device port: SMA or RP-SMA, pin or hole

- Antenna port: connector type and gender

- Panel feed-through: Yes / No

- Cable length: 0.1–2 m

- Waterproofing: Yes / No

- Quantity

Logic

- Match center-pin logic first (pin to hole).

- Confirm thread compatibility second.

- Decide whether a bulkhead is required based on enclosure layout, not convenience.

- Select the shortest length that satisfies placement and serviceability.

- Add sealing only if the environment demands it.

Outputs

- Recommended connector genders

- Extension type (M–F or M–M)

- Bulkhead required or not

- Suggested length tier

The value here isn’t the flowchart itself. It’s the discipline of forcing each assumption into the open before the order is placed.

Copy-ready PO note

A good PO line reads like a wiring instruction, not a catalog title:

“RP-SMA male to RP-SMA female extension cable, RG178, 0.3 m length, no bulkhead, indoor enclosure use.”

Suppliers rarely need to ask follow-up questions when the intent is explicit. That alone reduces lead-time friction.

Why small connector decisions grow into system-level issues

It’s tempting to treat connectors as interchangeable hardware. After all, they’re passive and inexpensive. In isolation, that’s true. In a system, they define interfaces—and interfaces define failure modes.

At higher Wi-Fi bands, especially 5 GHz and 6 GHz, connector choices influence:

- Insertion loss margin

- Return loss stability

- Radiated performance consistency

- Compliance headroom

None of these fail dramatically when something is off by a small amount. They fail quietly. Range shortens. Throughput fluctuates. Margins shrink just enough to make troubleshooting frustrating.

This is why experienced teams stop thinking of extensions and adapters as accessories. They treat them as part of the RF chain, subject to the same scrutiny as the antenna itself.

For teams that repeatedly ship products across different enclosures or markets, aligning connector logic early—and validating it against practical identification steps like those in the RP-SMA Connector Identification & Selection Guide—reduces downstream variability more than almost any other single habit.

Field answers to common engineering questions

How can I identify an RP-SMA port without opening the enclosure?

Look for external threads with no visible center pin. That combination almost always indicates RP-SMA female on routers and access points.

Does a 0.5 m extension hurt 6 GHz links much more than 0.3 m?

Yes. With thin coax like RG178, the additional loss is often enough to be noticeable, especially once connector losses are included.

Is using an adapter acceptable if everything still passes bench tests?

Sometimes—but it reduces margin. Bench success doesn’t guarantee long-term stability or compliance headroom.

Is a male-to-female jumper better than stacking two adapters internally?

Almost always. Fewer interfaces mean fewer discontinuities and less cumulative loss.

What bend radius is safe for RG178 in tight enclosures?

A practical rule is at least ten times the cable’s outer diameter. Violating that rarely fails immediately, but it degrades performance over time.

Should I add strain relief behind a panel bulkhead?

Yes. Even mild vibration benefits from it, and it helps preserve impedance consistency.

Final note

This figure serves as a summary illustration for the entire article, elevating the core message. It emphasizes that professional design and assembly aim for predictable electrical performance and long-term reliability that goes beyond mere physical connection.

One of the most persistent myths in RF assembly is that “if it fits, it’s fine.” With rp-sma connector systems, that assumption fails more often than people expect.

Matching means:

- Threads align

- Center contacts mate correctly

- Losses stay predictable

- Mechanical stress stays controlled

Fitting only guarantees the first of those.

When you identify ports visually, pair connectors deliberately, keep extensions short, and write POs that leave no room for interpretation, the RF chain stops being mysterious. It becomes boring—in the best possible way.

And boring RF hardware is usually hardware that ships on time, performs as expected, and doesn’t come back.

Bonfon Office Building, Longgang District, Shenzhen City, Guangdong Province, China

A China-based OEM/ODM RF communications supplier

Table of Contents

Owning your OEM/ODM/Private Label for Electronic Devices andComponents is now easier than ever.